Australian-based artist Khadim Ali introduces us to his weavers in Kabul, who demonstrate a fortitude characteristic of Hazara culture.

Khadim Ali, Invisible Border I, 2020, hand and machine embroidered, stitched and dye ink on fabric, 291 x 265cm. Collection: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. Photo: Marc Pricop.

Khadim Ali developed an interest in tapestries after his parent’s home in Pakistan had been destroyed by suicide bombers. All that was left was a collection of rugs. The current work in his touring exhibition Khadim Ali: Invisible Border reflects the grand narrative of battle in the Book of Shahnameh, a Persian epic that has functioned as a bedrock of Iranian identity for a thousand years.

Ali migrated to Australia in 2009 under the Distinguished Talent Visa, supported by the Queensland Art Gallery. Though trained as a miniature painter, he tried weaving as well but decided it was better to focus on design and collaborate with weavers to produce the final works. One of these weavers is Zuhra Rasooli.

- Marzia and Zuhra Rasooli at the loom

Zuhra comes from a family of seven children. As is common among Hazara, their home is decorated with embroidery. Her uncle, Sher Ali Hussaini, is a miniature artist who Khadim Ali met in Pakistan. They have since collaborated on many exhibitions, including the Australian War Memorial Museum.

Zuhra started weaving for Khadim when she was 18 years old, usually six hours a day. Until the recent takeover by the Taliban, Zuhra was studying art at Turquoise Mountain, painting miniatures and weaving her own works.

This is how Zuhra reflected on her situation in August 2021, as the Taliban was increasing its hold on Afghanistan.

Living in Afghanistan is a little bit scary. No one knows what will happen next and what the next day will be like. For women, working in art has its own difficulty. It’s hard to convince family that it is worthwhile. In the morning when I leave for university, I pray that I will be able to come back home.

At the moment everyone is wanting to leave Afghanistan. I want to stay here. Life is full of struggle. Sometimes we just want to give up and sometimes it is beautiful. We are human and deserve to be human. I am committed as an Afghan woman to show that we never give up. You have to be strong to win this game. These struggles make us human.

Zuhra lost her mother in 2017 and weaves with her sister Zahra. They push each other to take weaving to another level. They have increased the density from 16 knots her square centimetre to 25 knots. For Zuhra, this is part of the Hazara spirit of pesh boro, which she translates as “go forward and don’t give up”.

- Zuhra Rasooli

- Zuhra Rasooli

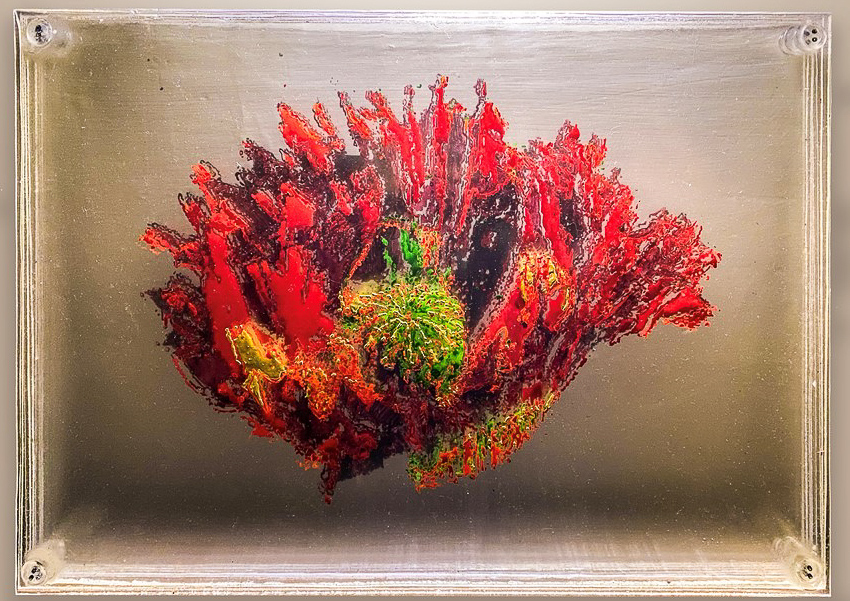

The opium flower

This is Zuhra Rasooli’s reflection on the opium poppy:

The opium flower is a plant from which narcotic substances are made. I thought even though this is a beautiful flower as we see, and also it is used to make medicine, but deep inside it is a danger. It can destroy lives. It can damage nature. Behind all its beauty, there is a dark situation if it is not controlled. In other words, it has many layers to be seen individually while it is the solid real form.

Practically this work has been done on nine acrylic transparent sheet layers applying two-dimensional shapes of different colour tones with a four mm gap of actual space inside each two layers. Playing with different mediums I was trying to have a three-dimensional effect of the flower at the same time that each shape is two dimensional.

Khadim Ali: Invisible Border is an Institute of Modern Art touring exhibition

About Zuhra Rasooli

Until August 2021, Zuhra Rasooli had been studying art. She expressed the wish that the name of herself and her sister be used in this article so that they are not forgotten.

Until August 2021, Zuhra Rasooli had been studying art. She expressed the wish that the name of herself and her sister be used in this article so that they are not forgotten.

Comments

Thank you Zuhra and Marzia for telling your story. To hear you speak of your desire to stay within you home country is heartening and brave. I trust pesh boro will lead you forward safely. Best wishes for being able to continue your creative path.