Chinese Ge Ba, detail, c. mid-Twentieth Century. Photographed by Mark Eden Schooley, with kind permission of Selvedge Magazine

中国格巴 细节 二十世纪中叶 由Mark Eden Schooley 拍摄 经由Selvedge杂志的善意许可

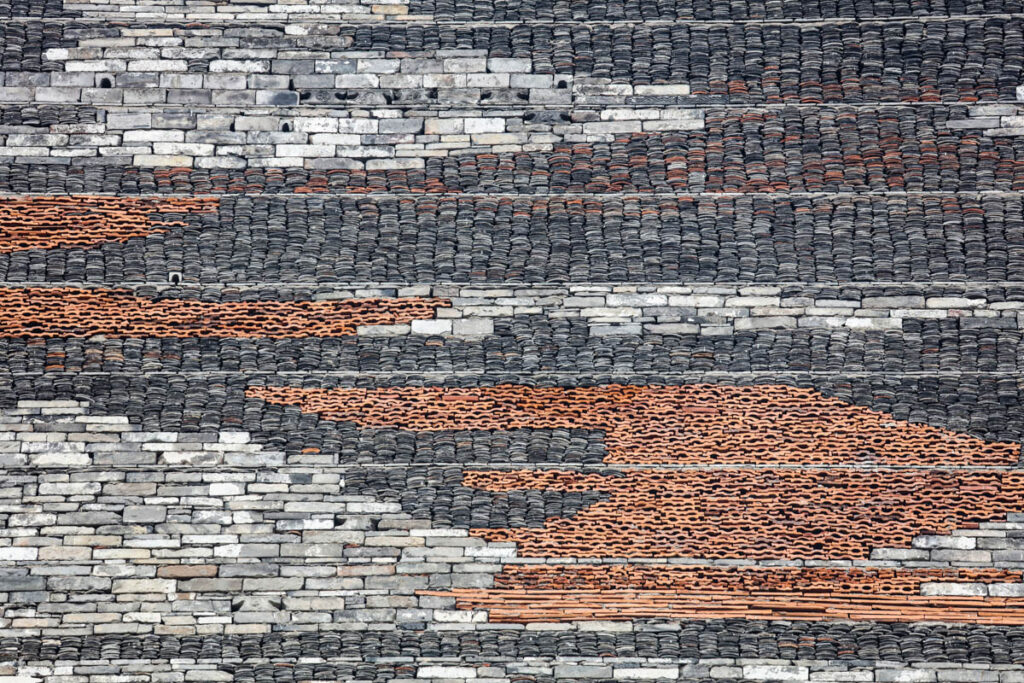

Amateur Architecture Studio, Exterior View of the Ningbo Historic Museum, Zhejiang, P.R China, 2008. Photographed by Finbarr Fallon. Arcaid Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

业余建筑工作室 宁波历史博物馆外景 浙江 中国 2008 Finbarr Fallon拍摄 Arcaid Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Peta Carlin finds a Chinese make-do folk craft in the work of Amateur Architecture Studio, as they attempt to keep stories alive in the debris. Peta Carlin(佩塔·卡林)在业余建筑工作室的作品中发现了一种中国临时民间工艺—试图在碎片中保留故事。

The nineteenth-century German architect and champion of the crafts, Gottfried Semper (1803-1879) was once to proclaim that weaving was the foundation of architecture, indeed, that the textile arts were the basis of all the arts, from which they derived their motifs and symbols (Semper and Mallgrave, 2004, p. 113). Extending upon this theme, in a lecture on the wall in antiquity delivered in 1853, he first put forth his concept of Bekleidungor dressing, the correlation between how we clothe the body and clad the naked structure of a building. This talk departed from observations of Chinese ornamental art, in which he noted that there was much to be learned from its designs and practices, and while markedly distinct, they nonetheless shared certain correspondences with other ancient civilisations, particularly so in the approach to the adornment of both body and building (Semper and Mallgrave, 1986, p. 34).

19世纪德国建筑师和工艺领域的冠军—戈特弗里德·森珀(1803-1879)曾宣称纺织是建筑的基础,事实上,纺织艺术是所有艺术的基础,它们从中派生出其主旨和象征(Semper and Mallgrave,2004,第113章)。在1853年的一次关于古代墙壁的演讲中,他扩展了这一主题,首次提出了“Bekleidungor dressing”的概念,即如何以衣蔽体和覆盖裸建筑结构之间的相互关系。这次谈话出发于对中国装饰艺术的观察,他在观察中指出,中国的设计和实践有很多值得学习的地方,尽管有明显的不同,但它们仍然与其他古代文明有着一定的联系,特别是在身体和建筑的装饰方法上(Semper and Mallgrave, 1986,第34页)。

Semper’s premise in relation to architecture and textiles, specifically in the context of China, remains as powerful today as it did at the time of its conception, correlations between Ge Ba, textile collages, and the work of Amateur Architecture Studio evidence of its potency.

戈特弗里德·森珀在建筑和纺织品方面所提出的,特别是在中国的背景下,格巴、纺织品拼贴画和业余建筑工作室的工作之间的相关性证明了它与诞生之时一样充满影响力,魅力未减。

Ge Ba emerged, it has been suggested, in the years surrounding the establishment of The People’s Republic of China in 1949, or conceivably even earlier, with the practice widespread in rural areas and not limited to any particular ethnic group, locale or region (Marks, 2017, p. 53). While its origins remain unclear, certain correspondences are nonetheless to be discerned with Japanese Boro textiles, not only in relation to the reuse and composition of fabric scraps (minus, however, the distinctive sashiko stitching), but also in terms of traditional Japanese aesthetic principles including mottainai: regret in the face of wastage (Boro -The Fabric of Life, 2013), or more simply put, an appreciation of the value of materials and things in general.

有人认为,格巴出现在1949年中华人民共和国成立前后的几年里,甚至更早,这种做法在农村地区普遍存在,不局限于任何特定的民族、地点或地域(Marks, 2017,第53页)。虽然它的起源尚不清楚,但仍然可以看出与日本褴褛”Boro”纺织品的某些对应关系,不仅与织物碎片的再利用和重组有关(然而,除去独特的刺子绣“sashiko”),而且在传统的日本美学原则方面,不能忽视的”mottainai”一词,意旨面对浪费的遗憾(Boro – fabric of Life, 2013),或者更简单地说,是带有欣赏的眼光看待世间万物。

Child’s Sleeping Mat (boro Shikimono); indigo-dyed cotton; late Nineteenth Century. 2017-15-1. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Museum purchase from General Acquisitions Endowment Fund. http://cprhw.tt/o/2FZ2Ng/.

儿童睡垫(boro Shikimono) 靛蓝染色棉布 19世纪末 2017-15-1 Cooper Hewitt 史密森尼设计博物馆 博物馆从一般文物捐赠基金购买

Chinese Ge Ba, c Mid-Twentieth Century, Photographed by Mark Eden Schooley with kind permission of Moowon.

中国格巴 二十世纪中期 由Mark Eden Schooley 拍摄 经由Moowon的善意许可

In the West, Ge Ba first came to light through the French art collector and trader, François Dautresme’s (1925-2002), happenstance discovery of an example in a cleaning supply store. The collector was fascinated by the beauty of objects from everyday life and amassed a vast collection of textiles and other artefacts over many years.

在西方,格巴最初是通过法国艺术收藏家和商人François Dautresme(1925-2002)在一家清洁用品店偶然发现而被人们认识。这位收藏家被日常生活物品的美丽所吸引,多年来积累了大量的纺织品和其他人工制品。

Measuring approximately 60 x 40 cm, these works are composed of between ten and fifteen pieces of fabric, the term itself said to mean “layers” (Kim, 2019)1.Ge Ba textiles, it would seem, are rarely discussed in China with scant academic references available, and after an initial survey, the official terminology in Mandarin has yet to be found. In general, however, these textiles are referred to as 纺织拼贴, which means “textile collage.” Ge is represented by 葛, a “textile material” or 格 “grid” or “pattern” and Ba 巴 means “patch.” It has been suggested that 格巴 “patch of patterns” represents the concept best because it is closest to the term for collage and because it expresses more closely the process in which the textile collages are made. With my thanks to Yurui Li 李禹锐 for his research and advice on this matter. with remnants sourced from all manner of scraps: threadbare garments, tattered fine embroideries and remainders of then contemporary cloths from the Maoist era (Marks, 2017, p.53).

这些作品的尺寸约为60 x 40厘米,由10到15块织物组成,这个术语本身可以理解为“层”的意思(Kim,2019),由各种各样来源的残碎材料所层叠而成:残破的衣服、破旧的刺绣品和毛泽东时代布料的剩余部分

Laid flat and stuck together with rice glue these surfaces were to be repurposed again and cut to serve as the soles of shoes or tailored to form the lining of new garments, their purpose not display but to operate as hidden interfaces.

这些铺平并用米浆粘连在一起的布料会被重新利用,切割成鞋底,或者剪裁成新衣服的衬里,它们的目的不是展示,而是作为隐藏的里料。

Despite their often short life as abstract compositions, pride in the arrangements of the fabric stuff was nonetheless taken, with local women gathering to judge the beauty of the arrangements, production taking place in their homes (Marks, 2017, p.53). Contemporaneous with the paintings of American Abstract Expressionists, this folk art appears thoroughly modern, the externalisation of the inner life of its artists bearing certain affinities with the afterlife of materials.

尽管作为抽象作品,它们的寿命往往很短,但对织物材料的排列可以让一些人从中汲取自豪感,当地妇女聚集在一起评判其美感,制作工作在她们的家中进行(Marks, 2017,第53页)。

这种民间艺术让人联想到了同时代的美国抽象表现主义者的绘画:艺术家内在生命的外化似乎与物质的重生有着特定的亲密联系。

Chinese Ge Ba, c. mid-Twentieth Century. Photographed by Mark Eden Schooley, with kind permission of Selvedge Magazine.

中国格巴 约诞生于二十世纪中叶 由Mark Eden Schooley拍摄 经由Selvedge杂志的善意许可

Mark Rothko, Multiform, 1948. National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Canberra, Australia. WikiArt. Mark Rothko《多形式》1948年出版 澳大利亚国家美术馆 Canberra 澳大利亚 WikiArt。

In the rubble of an area of Ningbo, the Yinzhou District, razed for the construction of a New Manhattan, Pritzker-Prize winning architect Wang Shu 王澍 was to discern traces of beauty, his practice Amateur Architecture Studio, established with his wife Lu Wenyu 陆文宇 in Hangzhou in 1997, winning the competition for the design of the city’s new history museum.

在宁波鄞州因新兴大都会的建设而拆毁的一片废墟中,普利兹克奖得主建筑师王澍辨出了美的痕迹,他与妻子陆文宇于1997年杭州创办的业余建筑工作室赢得了城市新历史博物馆的设计竞赛。

The site, once home to approximately 30 villages, now largely erased of memory, remained nonetheless generative and replete with potential. For, amidst the debris, traces were to be found, with bricks from the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368 – 1644 and 1636 – 1911 respectively) and even earlier discovered. These were reclaimed and provided much of the fabric for the facades and walls of the new building. Stripped of memory, the walls not only returned to former residents and locals the vestiges of their living past it but also revived a waning craft tradition. This technique, Wa Pan 瓦爿, literally meaning “tile,” was indigenous to the area and traditionally used by local farmers in the wake of destructive typhoons. All that was salvageable was gathered, sorted and reused to build their dwellings again. In the case of the museum and earlier projects, such as Xiangshan Campus of the China Academy of Arts in Hangzhou (2004, 2007), photographs were used to prompt the builders’ memories, many having to relearn the craft as it had since been forgotten (McGetrick, 2012).

这里曾经是大约30个村庄的所在地,现在大部分记忆都被抹去了,但仍然充满活力和潜力。因为,在废墟中,人们发现了明朝和清朝(分别是1368 – 1644年和1636 – 1911年)甚至更早时期砖的痕迹。这些材料被回收利用,并为新建筑编织外墙和墙壁。墙壁唤醒前居民和当地人过去在此生活的记忆,还恢复了日渐式微的工艺传统。这种技术,瓦爿,字面意思是“瓦”,是当地的土著传统,是当地农民在破坏性台风之后使用的。所有可回收的东西都被收集起来,分类再利用,重建他们的住所。在博物馆和更早的项目中,如中国美术学院杭州象山校区(2004,2007),照片被用来唤起建筑者的回忆,许多人不得不重新学习工艺,因为它已经被遗忘了(McGetrick, 2012)。

The building itself takes its form from nature and the multiform idea of a mountain. Mountains are long central to the Chinese way of life, with their Song Dynasty (960-1279) depictions a subject of deep fascination for the architect and enabling him to rethink the relationship between architecture, landscape, and surrounds (Shu and Luo, 2019, pp. 11-15 ).

建筑本身的形式来源于自然以及山川的多形态概念。自古以来,山一直是中国人生活方式的核心,宋朝时期(960-1279)对山的描绘令建筑师深深着迷,并使他重新思考建筑、景观和周遭环境之间的关系(Shu and Luo, 2019, pp. 11-15)。

Li Tang 李唐, Wind in the Pines Among a Myriad of Valleys, Southern Song Dynasty, 1124; source: WikiArt 李唐 《万壑松风图》 南宋 1124年 来源 WikiArt

Amateur Architecture Studio, Exterior View of the Ningbo Historic Museum, Zhejiang, China, 2008. Tada Images / Shutterstock 业余建筑工作室 宁波历史博物馆外景 浙江 中国 2008 Tada Images / Shutterstock

Architecturally classifying their structure whilst taking into consideration the facture of the surface, the flow of brush strokes and the drive of calligraphic inscriptions, spaces within the building were further conceived of as “valleys, caves, lakes” (McGetrick, 2012).

将山的结构进行了建筑性分类,同时考虑到表面的绘制手法、笔触的流动和书法题款含义的驱动,建筑内的空间进一步被构思为“山谷、洞穴、湖泊”(McGetrick, 2012)。

Mogao Caves, Thousand Buddha Grottoes, 27 July, 2011. Silk Road, Dunhuang, Gansu Province, P.R. China. Marcin Szymczak / Shutterstock.com 莫高窟 千佛窟 2011年7月27日 丝绸之路 敦煌 甘肃 中国 Marcin Szymczak / Shutterstock.com

Amateur Architecture Studio, Detail of Ningbo Historic Museum, 2008. Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China – 03 August, 2019. Tada Images / Shuttercock.com 业余建筑工作室 宁波历史博物馆细节 2008 中国浙江省宁波市 2019年8月3日 Tada Images / shuttercock.com

The project also calls to mind the ancient Library Cave at Dunhuang, properly known as Cave 17 at the Mogao Cave Complex in Dunhuang, Gansu Province, a cliff face carved into and punctuated by caves in which Buddhist and other religious scripts were stored. The surface, the irregular composition of this new repository’s façade, is composed of tile and brick which create patterns that are not only visual but textured and tactile. But unlike the ancient caves, the Ningbo History Museum preserves not only relics from the past, it also engenders and promotes living heritages as it recognises the value of materials. As such, both cloth and building, it could be said, are “inscribed in the natural chain of what man can produce if he is respectful of his past, and possessed of extraordinary manual dexterity when in tune with the rhythms of nature” (Asian Art Newspaper, 2017).2.This is how François Dautresme described his collection. The original quote reads: ‘These objects are inscribed in the natural chain of what man can produce if he is respectful of his past, with its extraordinary manual dexterity and possessed by the rhythms of nature.’

该项目还让人想起敦煌古老的藏书洞,被称为甘肃省敦煌莫高窟建筑群的第17窟,这个悬崖表面被雕刻出了一个个洞穴,其中储存着佛教和其他宗教的经文。这个奇特的储藏室的外观由不规则的瓷砖和瓦片组成,不仅具有视觉效果,而且具有纹理和质感。但与古代石窟不同的是,宁波历史博物馆不仅保留下过去的遗迹,还认识到物质的价值,制造并发扬“活”的遗产。因此,可以说,无论是布料还是建筑,都“铭刻在人类创造力的自然链中,如果他尊重自己的过去,并在与自然韵律的和谐中掌握超凡的灵巧技艺”(亚洲艺术报,2017)。

Acknowledgements

The completion of this essay was made possible by a Visiting Scholar position at the University of Canberra. With especial thanks to Sam Hinton, John Ting and the Library Staff.

声明这篇文章因由堪培拉大学的访问学者职位得以最终完成。特别鸣谢Sam Hinton, John Ting和图书馆的工作人员。

Further reading

Asian Art Newspaper (2017). Memories of China: Françoise Dautresme Collection. [online] Asian Art Newspaper. [Accessed 2 Aug. 2021].

Boro – The Fabric of Life. (2013). Lessac: Domaine de Boisbuchet [Exhibition] [Accessed 1 Jul. 2021].

Chau, H.-W. (2018). Wang Shu’s Design Practice and Ecological Phenomenology. ARQ: Architectural Research Quarterly, 22(4), pp.361–370.

Ge Ba. (2018). Paris: Françoise Livenac Penthièvre Gallery. [Exhibition] [Accessed 14 Mar. 2021].

Hobson, B. and Shu, W. (2016). Wang Shu’s Ningbo History Museum Built from the Remains of Demolished Villages. Dezeen. [Accessed 8 Jun. 2021]

International Dunhuang Project. The International Dunhuang Project: The Silk Road Online [online] [Accessed 8 May 2021].

Juul Holm, M., Kjeldsen, K. and Kallehauge, M. eds., (2017). Wang Shu Amateur Architecture Studio. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers.

Kim, M. (2018). Quest for Beauty: The Anonymous Artists of Chinese Textile Collages. Moowon [online]. [Accessed 8 Jun. 2021].

Leatherbarrow, D. (2020). ‘Wandering Sites: Wang Shu’s Hangzhou Guest House’. In: Building Time: Architecture, Event, and Experience. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, pp. 123-148.

McGetrick, B. (2012). Wang Shu: The Ningbo History Museum. Domus [online]. [Accessed 8 Jun. 2021].

Marks, S. (2017). Keeping Body and Soul Together: A Rare Collection of Chinese Ge Ba. Selvedge, 77, pp.48–53.

de Muynck, B. (2015). Translating Tradition for Modern Times. In: The Colours of … Frank O. Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Wang Shu and Other Architects. Basel: Birkhäuser, pp.152–223.

Semper, G., Mallgrave, H.F. and Robinson, M. (2004). Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts: or, Practical Aesthetics. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

Semper, G. and Mallgrave, H.F. (1986). The Development of the Wall and Wall Construction in Antiquity, London Lecture of November 18, 1853. Res: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics, (11), pp.33–42.

Shu, W. and Luo, L. (2019). The Narrative of the Mountain. Log, (45), pp.10-25.

Wada, Y.I. (2004). Boro no Bi: Beauty in Humility—Repaired Cotton Rags of Old Japan. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 484, pp.278–284.

Whitfield, R. and Whitfield, S. (2015). Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang. Art and History on the Silk Road. 2nd, rev. ed. Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publications.

About Peta Carlin

Peta Carlin is an artist and essayist. She holds a PhD, along with a Bachelor’s degree in architecture, and an Honours and a Masters degree in fine art imaging. Her work explores architectural themes and concepts through the practices of image-making with a view to collaborative exchange, and engages more broadly with architecture’s interaction with the other arts, with their shared histories. Invested in the poetics of place, her work seeks to bring forth the relational nature of the world in which we live. Peta is currently an Associate Professor in Architectural Design at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, P.R. China

Peta Carlin is an artist and essayist. She holds a PhD, along with a Bachelor’s degree in architecture, and an Honours and a Masters degree in fine art imaging. Her work explores architectural themes and concepts through the practices of image-making with a view to collaborative exchange, and engages more broadly with architecture’s interaction with the other arts, with their shared histories. Invested in the poetics of place, her work seeks to bring forth the relational nature of the world in which we live. Peta is currently an Associate Professor in Architectural Design at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, P.R. China

佩塔·卡林是一位艺术家和散文家。她拥有博士学位、建筑学学士学位、美术成像荣誉学位和硕士学位。她的工作是通过图像制作实践探索建筑主题和概念,以期进行合作交流,并更广泛地参与建筑与其他艺术的互动,以及它们共同的历史。她专注于地方诗学,试图揭示我们所生活的世界的自然关联性。佩塔目前是中国苏州西交利物浦大学建筑设计专业的副教授。

References

| ↑1 | Ge Ba textiles, it would seem, are rarely discussed in China with scant academic references available, and after an initial survey, the official terminology in Mandarin has yet to be found. In general, however, these textiles are referred to as 纺织拼贴, which means “textile collage.” Ge is represented by 葛, a “textile material” or 格 “grid” or “pattern” and Ba 巴 means “patch.” It has been suggested that 格巴 “patch of patterns” represents the concept best because it is closest to the term for collage and because it expresses more closely the process in which the textile collages are made. With my thanks to Yurui Li 李禹锐 for his research and advice on this matter. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This is how François Dautresme described his collection. The original quote reads: ‘These objects are inscribed in the natural chain of what man can produce if he is respectful of his past, with its extraordinary manual dexterity and possessed by the rhythms of nature.’ |

Comments

Absolutely fascinating. Thorough investigation. Relatable to several fields of art and study.