Lindy McSwan, Commonplace Vessels, 2021, Corrugated cardboard, handmade pigments made from rust, ironbark charcoal, limestone, quartz, and beeswax. 360 x 340 x 560mm, 300 x 290 x 450mm, Image Fred Kroh

Lindy McSwan’s vessels reflect the beauty of iron remnants as they lie rusting in the landscape.

(A message to the reader.)

My first research field trip was on Barngarla country in South Australia, to the small rural township of Iron Knob and the iron ore mining area of the Middleback Ranges. This field trip included a visit to the nearby Whyalla steelworks which uses iron ore from the local mines to produce iron and steel. Sometime later I travelled to Dharawal country visiting the Port Kembla steelworks south of Wollongong in New South Wales.

At each site, I had opportunities to source, through being given and otherwise collecting physical material. In addition to iron ore, I collected limestone and quartz, materials used as fluxes in the process of steelmaking to separate and remove impurities by forming slag when iron ore is made into molten iron in a blast furnace. The collection of visual material, through photography at the sites, came to play a significant role in my research project.

The life cycle of steel begins with iron ore, the primary material essential to iron and steelmaking. Steel is a unique man-made material that when not recycled at the end of its useful life, if exposed to oxygen and moisture, naturally rusts and disintegrates.

The fundamental materials of my practice include, and are somewhere in between the materials seen in the image Iron ore and rusted steel on the roadside near Iron Knob. The materials pictured, iron ore and rusted steel, are both forms of iron oxide and illustrate perfectly the beginning and end of the life cycle of steel.

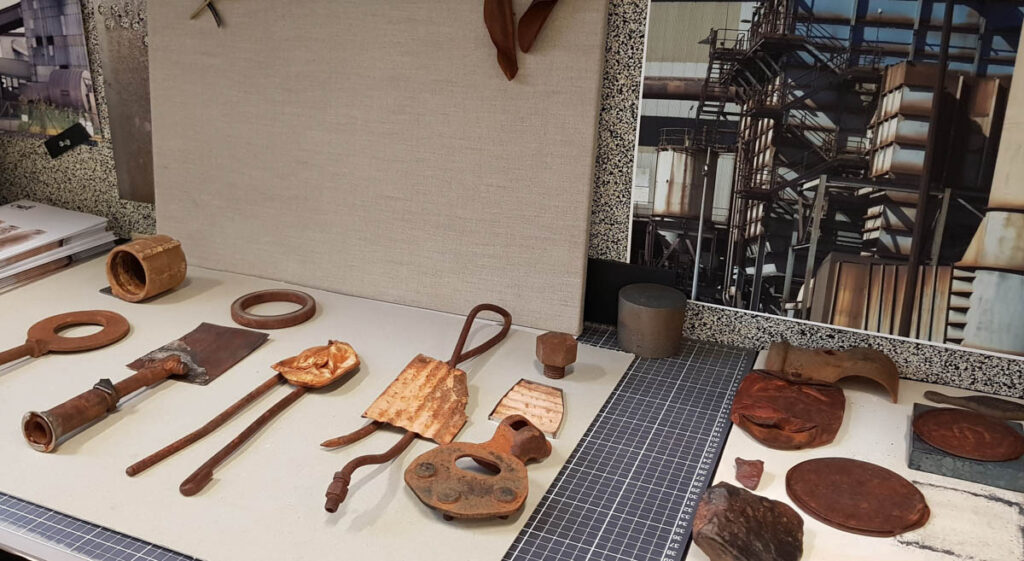

Found rusted steel objects are always present on my studio bench. The most valued rusted objects were found on remote desert tracks in Central Australia where they lay, rusting away in a sympathetic, iron oxide-rich landscape. I take care in storing these objects to preserve their imperfect patina that has come about through the object’s long exposure to oxygen and moisture aided by extremes in weather.

These rusty surfaces have developed over considerable time and many seasons. Sand and wind have naturally blasted away all or most of any protective coating. Wind, rain, and blazing sun have burnished, baked and hardened their surfaces. In contemplating these objects, I consider the notion of the distance of time. In many cases, they are broken fragments of unknown purpose, each with a story and sometimes a sense of mystery. If I had not interrupted the corrosion process in the material life cycle of these found rusted objects by collecting them, they would eventually break down and rust away into the sandy desert ground where they lay discarded.

Lindy McSwan, Of Dust and Rust, 2018 – 2019, Mild steel – heat coloured, found rusted steel objects. Dimensions vary: 70 x 70 x 330 mm (longest at left), Image Andrew Barcham

There is a rare and special quality to each found rusted object, such that I cannot change or remove any part of it. A self-imposed rule forbids alteration by filing, cutting, or drilling thereby adding to the challenge of using these objects. These precious found treasures sit on the studio bench for a considerable time before I begin working with them. I hold and examine them repeatedly, contemplating how to acknowledge their uniqueness in bringing them new life.

Gradually a piece develops around each fragment by first crafting a fine case or bezel from mild steel to hold the object gently but securely. Then one by one a vessel or sculptural form develops, again using mild steel. Each vessel or sculptural form is unique and an extension of the found rusted object. The vessel crafted around each object is blackened by heat colouring, giving further contrast to the old and new material, and emphasising form.

In making new work with found rusted objects, this collection, Of Dust and Rust, also considers the unique and recyclable potential of steel and its ability to be continually recycled. The addition of scrap steel is necessary in the process of steelmaking, where, for every 100 tonnes of molten iron used in making new steel, 30 tonnes of scrap steel is added.

As an ultimate by-product of steel left to deteriorate and corrode, the material potential and qualities of rust became more important to my research. Scraps of steel from vessel making were used to make a vibrant rust infusion that was used as a pigment in making a collection of work titled Commonplace Vessels.

The ubiquitous corrugated cardboard box is a familiar everyday object. During the very long and repeated COVID pandemic lockdowns in Melbourne over 2020-21, quite unexpectedly, they became material to contemplate and create notions of containment as a new collection of vessels.

Using what was available to me at home, deconstructed cardboard boxes were reconstructed as vessels. Handmade pigments were ground and made from collected rust, quartz and limestone, and ironbark charcoal we use in a barbecue grill. I continued this material exploration using finely ground rust and charcoal, individually, with melted beeswax (from our bee hives) to make crayons. The crayons were used to build layers and surfaces on the works Commonplace Vessels.

The site of the Port Kembla steelworks is a labyrinth spread across nearly ten kilometres. Photography was a method I used to closely examine layers of detail in this industrial landscape that was at first overwhelming, yet compelling to my aesthetic sense. Given the scale of the steelworks, even an area of detail is monumental. Photography became a method to focus on the forms, geometry, materials and patinas of the steelwork’s sites. My photograph titled Port Kembla Steelworks, Super Detail with Blue and Red is an example. Such detail is bold and graphic and serves to bring forth ideas when I return to the studio where photographs of similar detail are placed on the walls.

Lindy McSwan, To Cart Carry Convey, 2022, Mild steel, vitreous enamel, iron ore. Dimensions vary Image Fred Kroh

In developing the surface for a collection of vessels titled, To Cart Carry Convey, I experimented with blending ground iron ore and vitreous enamel. The iron ore was slowly ground by hand using a diamond-coated tool and water to make a rich reddish-brown slurry.

There are many variables in the practice of enamelling. Typically when testing, I change one variable at a time, for example, the kiln temperature or time in the kiln. After extensive experimentation and dozens of enamel test pieces, I created a range of samples achieving tonal variations and surface finishes I was happy with. These vitreous enamel mixes are then applied to the final enamel firings on a vessel. Regardless of how much testing is done beforehand, the application of enamel to the much larger surface of a vessel inevitably has some unexpected outcomes. After carefully taking a fired vessel out of the hot kiln for the last time, the colour and surface texture is revealed, and I breathe a slow and deep sigh of relief.

I have come to regard the steelworks visited on my field trips as a system of vessels. Their structures, mostly made of steel, transport, store, and process material in the production of iron and steel. Kilometres of rail networks, carriages, monumental industrial vessels, conveyors, furnaces, cavernous, corrugated steel sheds and forming systems, empty, fill, move, transform, and contain vast quantities of material in a continuous process of steelmaking. This work, To Cart Carry Convey, reflects on this experience as well as notions of containment embodied in the vessel more broadly.

Note

The mild steel vessel has been the foundation of my practice since the final year (2012) of my undergraduate studies in gold and silversmithing. In recent years, I have developed a deeper material focus that considers the material properties, qualities, and transformations in the life cycle of steel. The materials and sites of iron and steelmaking are the focus of my Master of Fine Arts research project titled, Material sites: observations of the Australian steel industry through the vessel.

About Lindy McSwan

Lindy McSwan’s creative practice is founded in gold and silversmithing. The qualities and potential of material and experience of place are the foundation of Lindy’s artwork. Her palette of materials includes steel, vitreous enamel, found rusted objects, cardboard, paper, handmade pigments, and fabric. With her work To Cart Carry Convey, discussed in this story, Lindy was selected as a finalist in the inaugural 2022 Robert Foster F!NK National Metal Prize, currently showing at Craft ACT, Canberra until December 10, 2022. In February 2023, the creative outcomes of Lindy’s MFA research project will be exhibited at Site Eight Gallery, in the School of Art, RMIT University, Melbourne. Follow @lindymcswan.

Lindy McSwan’s creative practice is founded in gold and silversmithing. The qualities and potential of material and experience of place are the foundation of Lindy’s artwork. Her palette of materials includes steel, vitreous enamel, found rusted objects, cardboard, paper, handmade pigments, and fabric. With her work To Cart Carry Convey, discussed in this story, Lindy was selected as a finalist in the inaugural 2022 Robert Foster F!NK National Metal Prize, currently showing at Craft ACT, Canberra until December 10, 2022. In February 2023, the creative outcomes of Lindy’s MFA research project will be exhibited at Site Eight Gallery, in the School of Art, RMIT University, Melbourne. Follow @lindymcswan.

Comments

What particularly resonated for me was “ These precious found treasures sit on the studio bench for a considerable time before I begin working with them. I hold and examine them repeatedly, contemplating how to acknowledge their uniqueness in bringing them new life.”

This is what most people don’t understand about making art, it takes time….sitting contemplating, thinking, experimenting, making…and sometimes it comes to fruition.

Wonderful work, Lindy.