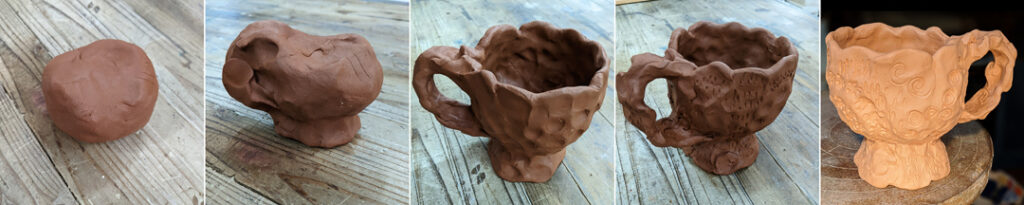

Toni Warbuton, Chalice for the Troposphere with Cloud Cups, hand-formed terracotta with sgraffito under white and coloured glazes. 2023. photo: MK Images

Toni Warburton describes the sounds that orchestrate her work in ceramics.

I seldom listen to the radio or other voice or music forms while working with clay in my studio. I find the rhythm gets into my body and alters the natural rhythms of touch, affect and response that engender the mindfulness that enables me to collaborate with clay—uncannily, in that the work often seems to make itself.

I say I work in silence, but that is not quite true. In my studio, my work is embodied in the ambient sounds of the analogue here and now. An old main road passes through our village. I hear the rumble of supply trucks, cars, police, ambulance and fire brigade sirens, the voices from a peloton of bike riders will drift past. If it’s a sunny day, someone will mow a lawn somewhere. I can assure you that industrial sounds are not just the province of the city. There is a pub a couple of fields away with an open mike, bands and sometimes fireworks on weekends.

In my studio, these sounds are muffled, and I hear parrots squawking through the trees, musical magpies, field currawongs, kookaburra cadences, a raucous cackle from a flock of sulphur-crested cockatoos, the twitter and flutter of wrens and sparrows, and an occasional squawk as a pair of glossy black cockatoos glide by. When it’s raining, the wind brushes pine fronds against the window panes.

And subtle sounds emanate from the processes transforming the clay and me. To begin, the thump of a block of clay on the marine ply wedging table. Then the slick, stick and release as the plastic bag peels off the damp clay. My twisted wire cuts off a chunk of clay the size of a loaf of bread. I knead the clay in a spiral motion of soft rhythmic sounds as my body weight leans back and forth, and my hands press and rock the clay into a basin-like form with a spiral on top like a perfect apple tarte tatin. The spiral basin is thwacked into an oblong block that the wire cuts in two. One half is turned and intently splatted onto the other.

Another thwack, another cut. This wedging rhythm continues, somewhat trance-like, until the clay grain looks and feels right, perhaps about twenty times. My phone rings. I don’t answer. My hands are coated with a film of terracotta clay. I wear an apron of sturdy cotton cloth. It too is smeared with clay. I cut the block of clay into fist-sized chunks and rustle them inside a plastic bag to keep them moist. Each lump is tossed from one cupped hand to the other. Turned and tossed: slap slap slap, the ball of clay compresses into a sphere that I either hand model into forms, a process I call “topological investigations”, or throw on the pottery wheel.

I am carving cloud motifs into the surface of a ritual vessel in the shape of a cloud cup that I have modelled from a single lump of clay. In the background, there is always the intermittent swish of rubber on asphalt as cars travel the highway. Very close sounds, my breath… or not my breath, because sometimes when I concentrate, I hold my breath… clearing my throat.

I have a cluster of fine wooden modelling tools, smooth and softened from use. My hand guides and the wooden tool glides silently through the leather-hard clay. There is just enough resistance to hold the curved line that meanders and flutters over the contours of the form. I hold the cup by its belly, careful not to put pressure on its elaborate handle.

The hollow of the cup is fingerprint dappled and close to my face. My voice would resonate in the small cavity if I spoke or uttered a sound. Perhaps I will sing… a cloud song… of spirals, dots, and arabesques! The song is already written, for sure. How can I find it? It could be a song by Marais played on the viol da gamba.

As the tip of the wood gouges lines, a bur of tiny rice grain-sized clay pellets kicks up. These tap, tap, fall, onto the Masonite disk I use to carry the cup. Occasionally, I use my fingers to swish-sweep these grains into a pile. Then I lift the disk and tilt-tap it on the edge of a plastic container. As they slide, the pellets sound a tiny echo of gravel being swept and poured, a shoal-like sound, like hail falling in miniature. Amplified, it would be a chorus of very young children’s voices singing in unison.

A couple of the dry wooden tools tinkle together on the bench as I bump them. The rest are in a cylindrical tin with just enough space to jostle them to find the one I want. The tinkle in the can is more sonorous, like a dry seedpod rattle. Tap water sputters and purrs into the little stainless steel sink to clean my tools and wash my hands.

A wooden paddle beats a hollow clay form into shape: pat thud, pat thud, pat pat, thud thud. Tap, tap, to centre an upside-down pot on the wheel for a metal blade to shave the clay and turn a foot.

The whirr of spinning electric wheels, punctuated by the chuck, chuck of a couple of kick wheels, the splat of a collapsed pot, the splish of fingers in water bowls, the trickle drops of water from a sponge onto a centred cone of clay.

One of the most peaceful rooms in my world of experience is a room on the ground floor of a stone building with tall windows along one side. It has cave-like seclusion and dampness to its atmosphere, and it buzzes with a sonorous hum. It is the throwing room at the National Art School in Sydney. The whirr of spinning electric wheels, punctuated by the chuck, chuck of a couple of kick wheels, the splat of a collapsed pot, the splish of fingers in water bowls, the trickle drops of water from a sponge onto a centred cone of clay. The change of gear of wheel motors to accommodate the slower spin for large pots and faster for centring the clay.

An occasional soft voice of advice from a teacher placates a beginner’s groan of exasperation. All of this – and the churn of the dough mixer, the chug of pugmills, and water running in a concrete sink in the adjoining clay reclaim room, creates a rhythmic soundtrack to the perpetual choreography of generations of students practising the potter’s art.

To pass through this room and hear the peaceful hum, like a moist fingertip singing around the rim of a glass, could, it seems, herald a redemptive visit from a flying saucer from another time zone. I’ve heard it said a gramophone needle could track the grooves on an ancient pot to play back the ambient sounds of the place where it was made.

Clay slips of different colours may be painted or poured over clay forms stiffened leather-hard. The gestures of slip and glaze processes generate liquid sounds. The chortle of brushes being rinsed of their pigments in clean water. Whisking, pouring, stirring, splashing, dipping, modulated by rhythms of contour, the number of forms to be coated and the volumes of liquids. Vessels may be plunged, mouth down into a bucket of slip, so a quick upwards movement that stops short of the meniscus will draw the slip up inside the cup with a delicious, playful, suction slurp.

Clay forms dry slowly and become fragile in the sun and breeze. Should a crack happen, a firm thud will shatter the form. Wooden mallet thumps crush the fragments to be slaked in water, then squelched and squished onto a plaster bat to stiffen.

The kiln is packed, ready for its thermocouple-controlled gradient of heating and cooling: click, long pause, clock of the energy regulator on-off switch, and the constant whirr of the exhaust fan. I have an idea that if amplified, the sounds of clay being turned into ceramic in a kiln could be akin to sounds made by weather and geological transformations. The impact of heat on rocks, evaporation, the release of steam, the vapours of combustion of carbonaceous matter in the clay, heating and cooling cause expansion and contraction of quartz cristobalite.

Tasmanian potter Neil Hoffman has coined the term “kiln weather” to describe the atmosphere in a wood-fired kiln. Seasoned wood firers would be the ones to give accounts of listening to the various songs of wood-fueled fire as it weaves its draft through different kinds of kilns.

Hear the ping, ting, ping inside the kiln as glazes cool and shrink over surfaces. Listen for the resonant ding when you tap a well-fired ceramic piece. A leaden dupp is the clue to a crack. Round and round, a grinding stone will smooth the base. With the catastrophic smash and tinkle of broken pottery, a hammer shatters it into shards that rattle until crushed to pellets of chamotte to temper another round of clay on its journey.

About Toni Warburton

I have been working with clay for over 50 years. Col Levy was my inspirational teacher at the National Art School where I obtained my Diploma of Art Education in 1973. I then learnt the practice of throwing as an apprentice potter with Richard Brooks who had trained in the Leach tradition. Mostly I now hand build and fire my work in electric kilns and pay the subsidy for green electricity. Nonetheless, I love to fire my work with wood, a sustainable fuel, and have acquired a small portable wood fire kiln designed and made by Steve Harrison. For many years I have lectured in Ceramic history and theory at Sydney Art Schools. My work is often concept-driven and quite experimental. Catchment, my Master of Visual Arts by research was completed in the Glass studio at Sydney College of the Arts. After maintaining studios at the Glebe Estate workshop and then in Marrickville, I have recently relocated to the countryside. My studio, a 1912 timber school room is surrounded by trees in an old garden on the five-acre site of an old school. As well as tending the garden, my husband, Chris Ward and I are gradually de-weeding the land from blackberry, gorse and privet and rewilding the place with Australian bush plants.

I have been working with clay for over 50 years. Col Levy was my inspirational teacher at the National Art School where I obtained my Diploma of Art Education in 1973. I then learnt the practice of throwing as an apprentice potter with Richard Brooks who had trained in the Leach tradition. Mostly I now hand build and fire my work in electric kilns and pay the subsidy for green electricity. Nonetheless, I love to fire my work with wood, a sustainable fuel, and have acquired a small portable wood fire kiln designed and made by Steve Harrison. For many years I have lectured in Ceramic history and theory at Sydney Art Schools. My work is often concept-driven and quite experimental. Catchment, my Master of Visual Arts by research was completed in the Glass studio at Sydney College of the Arts. After maintaining studios at the Glebe Estate workshop and then in Marrickville, I have recently relocated to the countryside. My studio, a 1912 timber school room is surrounded by trees in an old garden on the five-acre site of an old school. As well as tending the garden, my husband, Chris Ward and I are gradually de-weeding the land from blackberry, gorse and privet and rewilding the place with Australian bush plants.

Postscript on sounds of wood-firing from Neil Hoffman

When wood firing my kiln, a firestorm builds. It’s a weather event of sorts where burning wood generates extreme heat, wind, and airborne matter. Fire is meeting clay inside a double-skinned brick volume, this kiln wall protecting anyone outside it from the heat within.

Matches are struck to get things started. Wood is split. Popping sounds come with both light and heavy stokes of dry wood. More sounds come with my prodding the wood on the firebox hobs and with the dropping and splashing of partly burnt logs onto the ember bed below. The chimney sucks fine ash through the kiln to land softly on objects. Here wood turns to glass: no loud rock-crushing machines, no noisy blower-assist furnaces for its making.

Occasionally, a stoke of green wood brings silence, and the only sound I hear is from inside my head, “Why not more care with wood preparation?” Wet wood is “quiet” wood, and this silence sounds an alarm signalling a probable temperature drop.

With this quiet, my attention wanders to my bush surroundings. I now hear what has been gifted to us over millennia. I’m now hearing trees and wind, birds and song, and scampering marsupials, all testament to another “weather” of sorts—” cosmological evolution spanning infinite space and time. I wonder about the sounds and songs of the universe at large, that greater space, the place of life’s very beginnings.

Neil Hoffmann, woodfirer, Reedy Marsh, Tasmania.