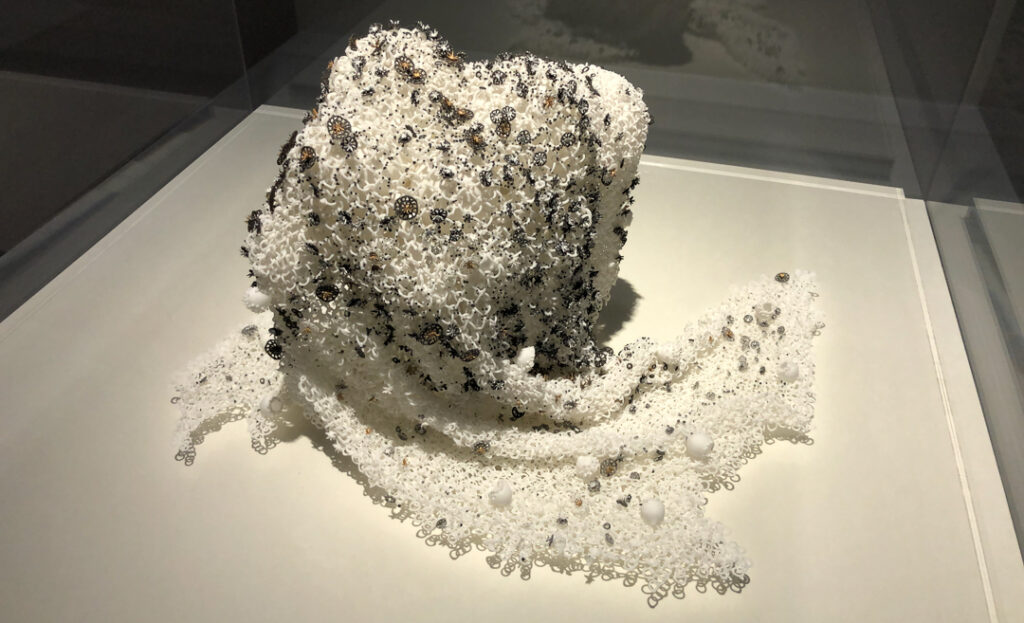

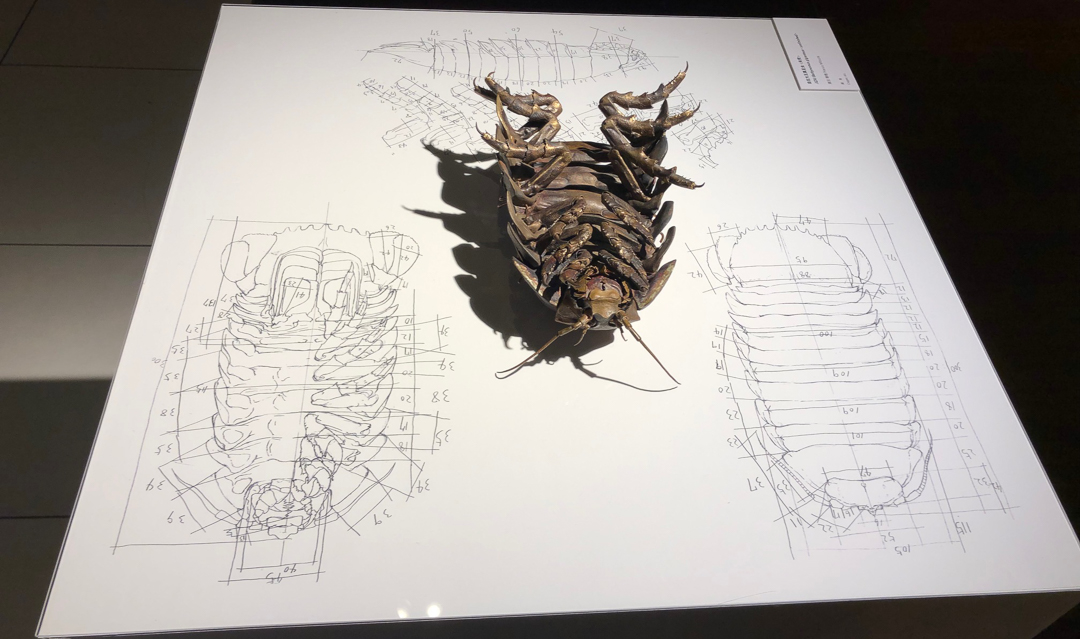

“Nirvana”(2021) by MATSUMOTO Ryo; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at Mitsui Memorial Museum (the exhibition of Tokyo Venue: September 12 – November 26, 2023)

Sachiko Tamashige heralds a remarkable new generation inspired by the hyper-realism of the Meiji era.

“Wow, it looks like the real thing,” “It’s so amazing,” exclamations from visitors can be heard from the venue of the exhibition. Many works leave adults and children with their mouths hanging open, such as flowers, fruits and animals that are so realistic, butterflies and everyday objects, crabs and dragons that move freely, and vessels and objects with highly detailed and elaborate decoration.

The exhibition In the Genes, Taking Marvelous Meiji Craftmanship into the Future, which you can enjoy just by looking at the exhibition without any prior knowledge, is touring seven venues across Japan until 2025. It is currently on display at the Mitsui Memorial Museum of Art in Nihonbashi, Tokyo until November 26th.

This is an exhibition that introduces the works of fine crafts of the Meiji (1868-1912) period, as well as the latest works of contemporary artists who have inherited the genes of those superb Meiji craftsmanship.

In recent years, Meiji crafts, or Meiji Kogei in Japanese1.A wide variety of crafts such as cloisonné, metalwork, ivory carving, wood carving, lacquer work, and embroidered paintings were created during the late Edo and the Meiji periods, mainly for export. During the Meiji Restoration, craftsmen for sword fittings such as metalwork and lacquer artisans who used to be employed by the feudal lords and lost patronage of the samurai began to produce objects for commercial export to the West. They also encountered Western culture and created fine crafts that had never been seen before. The finest pieces made with outstanding techniques by leading master craftsmen, who were designated as “ Teishitsugigeiin(帝室技芸員,” or artists under the patronage of the imperial household, such as a cloisonne maker NAMIKAWA Yasuyuki and a metalworker UNNO Shomin, were housed in the imperial collection or leaked overseas, and the general public in Japan could hardly see them., have been attracting attention in Japan. These fine crafts were made in a wide variety of fields such as cloisonné, metalwork, tusk carving, wood carving, lacquer work, and embroidered paintings during the Meiji period. Most of them were sold overseas, therefore rarely seen in Japan, and were forgotten for nearly 100 years.

From the end of the 1980s, Mr Masayuki Murata, the director of the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum of Art, bought back superior pieces of Meiji crafts from overseas, opened the museum in Kyoto and started showing his collection in 2000. Since then, his collection has been shown in touring exhibitions in Tokyo and other cities which contributed to raising the recognition of the excellence of Meiji Crafts.

From 2014 to 2015, the exhibition Kogei – Superlative Craftsmanship from Meiji Japan (Japanese title”超絶技巧! 明治工芸の粋ー村田コレクション一挙公開ー”) which showed a superb selection of Murata collection, began at the Mitsui Memorial Museum and toured six cities, attracting over 200,000 visitors in total. This exhibition, whose Japanese title carries a catch phrase “Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧),” or “ transcendent techniques” 2.“Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧)”, or “transcendent technique” “extraordinary skill”. “Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧)”, was used in the music world to accomplish marvellous technique for instruments as seen in the piano etude “Études d’exécution transcendante” (Transcendental Études) composed by Franz Liszt. It was the supervisor Mr Yuji Yamashita who gave Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧) as the Japanese title of the series of Meiji Kogei exhibitions. “Chozetsugiko” works like a catchphrase which appeal immediately the excellence of Meiji crafts which were made with extraordinary technique by the master craftsmanship of the Meiji period. Mr Yamashita, used to practice playing the koto, or a Japanese zither, passionately to accomplish “Chozetsugiko” technique to become a professional koto player when he was young. Instead, he became an eminent art historian of Japanese classic arts, He chose to use “Chozetsugiko” for the exhibition of Meiji crafts, based on the memories engraved in his body, as he himself was astonished by superb Meiji craftsmanship, the overwhelming technical ability that anyone can understand immediately. But the word “Chozetsugiko” is so appealing that it tends to be overused for different situations these days. was so successful that subsequently two more exhibitions using “chozetsugiko” for its Japanese title were organized although it was not used for English title. In the Genes, Taking Marvelous Meiji Craftmanship into the Future, which I mentioned at the beginning and will discuss mainly in this article, is the third one of a series of Chozetsugiko, exhibitions.

All these three exhibitions were supervised by Mr Yuji Yamashita, the art historian who specialised in classical Japanese art during the Muromachi period (approximately 1336-1573). It was Mr Yamashita who decided to use “chozetsugiko” for the Japanese title in a series of exhibitions, as he thought that “chozetsugiko” was an appropriate keyword to convey immediately the characteristics and excellence of Meiji crafts. The series of Chozetsugiko exhibitions with the Murata collection increased the interest of people and became momentum for the re-evaluation of Meiji crafts.

“At the first exhibition of Chozetsugiko, we exhibited only the works of master class Meiji craftsmen from the Murata Collection, and I thought their outstanding techniques were lost technology. However, the first exhibition might have stimulated the younger generation of artists and some artists emerged, who are striving to possess the transcendent techniques and expressive power of Meiji craftsmanship. In the second and third exhibitions, the works by contemporary artists were exhibited. In the third one, the present exhibition, you can see the further evolution of this transcendent technique. Along with the masterpieces of Meiji crafts, we are introducing new works by 17 contemporary artists who inherit their DNA and venture into new areas by making full use of diverse materials and techniques.” said Ms. Yuko Kobayashi, a curator of the Mitsui Memorial Museum, who has been involved in the planning since the first exhibition.

“As a result of the second project, we received a call from the bereaved family of ANDO Ryokuzan, whose details such as years of birth and death were unknown until then, and academic research into Meiji crafts also progressed”, Ms. Kobayashi added.

This series of exhibitions of chozetsugiko has been covered in newspapers, magazines, and television programs, in Japan. As a result, Meiji Kogei, or Meiji crafts became known to the general public with the word ”chozetsugiko”. In addition, by witnessing the masterpieces of Meiji crafts, contemporary artists are also learning from the outstanding craftsmanship of Meiji crafts, and are working to evolve a new field of fine crafts with modern sensibilities, new techniques and concepts.

MAEHARA Fuyuki

MAEHARA Fuyuki, “A moment : Dried cuttlefish and sake cup”, 2022; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023)

A squid with rusted metal fittings has a wooden clothes peg attached. This is a wood carving work by MAEHARA Fuyuki (1962-) (61 years old), “A moment: Dried cuttlefish and sake cup” (2022). While looking at it, I was almost salivating. The craftsmanship is astounding. The clothes peg, metal fittings, and squid are carved from a single piece of wood. MAERAHA’s motifs are common, trivial or abandoned things that people don’t pay attention to. “Even if the object is abandoned or decays, it gives off the feeling that it has always been there. I am carving out that time,” said Mr Maehara.

Mr Yamashita, who has been paying close attention to MAEHARA’s works for the past 20 years, said that he was “deeply astonished” when he first saw MAEHARA’s wood carving piece called “Ikkoku: Barbed Wire.”

“MAEHARA had carved out such pathetic motifs in a super-realistic way. I was even more surprised to see that they were all made of a single piece of wood.” Mr Yamashita said, looking back on MAEHARA’s work, which took one to two years to carve the wood with precision, and describes his work as “the divine work of a monk in training” and “the ultimate wabi-sabi.”

FUKUDA Toru

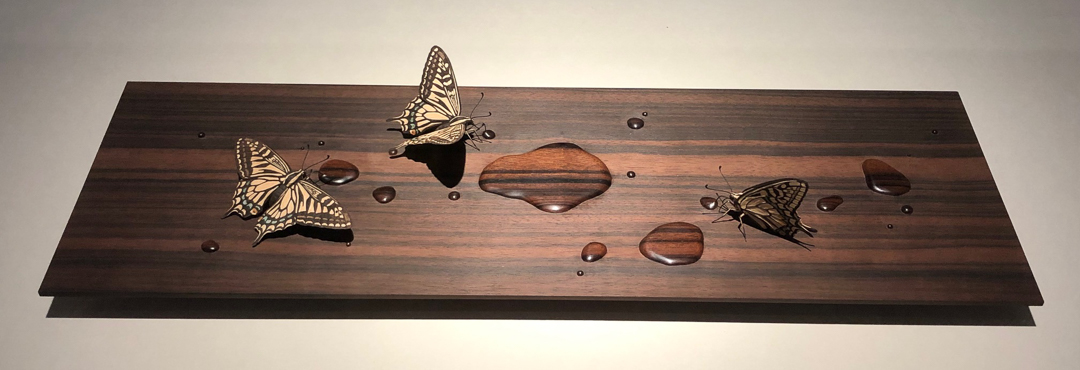

“Puddling”(2022) by FUKUDA Toru; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

The youngest artist in this exhibition, FUKUDA Toru (1994-) (29 years old), wanted to try painting with wood, so he developed a unique technique called three-dimensional wood inlay, and created the work “Puddling” (2022), depicting the scene of swallowtail butterflies absorbing water from droplets using cut out wooden parts of various colors and fitted them three-dimensionally. What is surprising is that the wood is not coloured, and the water droplets are also made by carving and polishing the base wood.

“MAEHARA uses a single piece of wood and paints it, while FUKUDA uses three-dimensional inlays and does not paint them. Each of them challenges to transcendent techniques using their own aesthetic rules of technique,” said Mr Yamashita.

OTAKE Ryoho

“Moonlight ” (2020) by OTAKE Ryoho when it was in full bloom after Mr.Otake’s watering; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

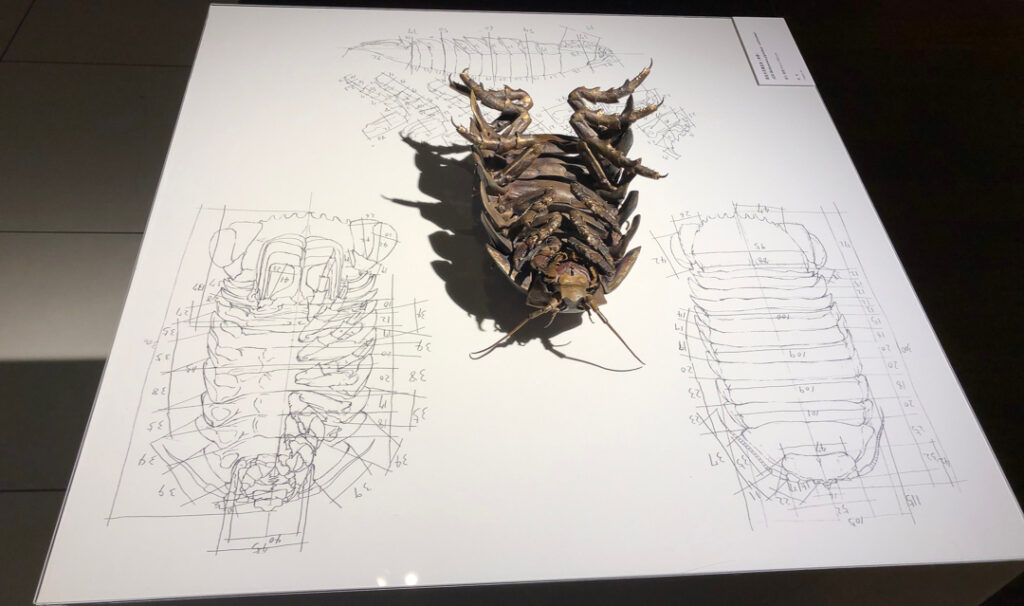

“Moonlight” (2020) is a work by OTAKE Ryoho (1989-) (34 years old), who has mastered the art of Jizai3. Jizai=Jizai-okimono, or Jizai ornament. Jizai is primarily a branch of Japanese metal crafts. They are made of metal plates such as iron, copper and silver, in the form of animal ornaments such as dragons, snakes, birds, spiny lobsters, crabs, and butterflies. It is realistic and the body segments and joints can be moved just like the real thing. Contemporary artists started making Jizai by using other materials such as wood or ceramic. wood carving. When water is poured into the vase, the 47 white petals of Dutchman Pipe Cactus, or A Queen of the Night (月下美人), made from deer antlers, slowly open. OTAKE’s works do not simply resemble the appearance of motifs, but also accurately model the structures and mechanisms of living things. “By doing so, I feel I can get a little closer to the meaning behind the creation of life.”

OTAKE’s interest then turned to the human body, and he asked, “What makes humans human?” and came up with the idea that “humanity can be concentrated in the movement of the hands. It is said that human hands have a structure that is not found in other animals.” “Innocent” (2023) is the latest work by OTAKE that uses an anatomical approach as a motif of the human hand. This work is a Jizai work that perfectly reproduces the delicate movements of the human hand, and in the future, there are plans to complete it as a work in which fingers move using the power of water.

HONGO Shinya

“Visible 01 Border” (2021) by HONGO Shinya and Mr.Hongo stood explaining his work; ; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

HONGO Shinya (1984-, age 39) creates his works using iron forging, a particularly difficult form of forging where metal is hammered into shape. He says, “I want to give form to life with iron. I believe that iron, which easily rusts and decays over time, is the most suitable material.” He heats up a construction iron plate and hammers it into the shape he envisions. He starts working on his object without creating any blueprints or prototypes. For HONGO, iron is “something that can be changed freely, just like clay.’’

His work “Visible 01 Border” (2021) is a life-sized crow whose shiny black feathers are precisely produced. The internal skeleton of the crow which cannot be seen with the naked eye, and the “plastic candy bag” that was accidentally swallowed and made of silver, are visible as they are exposed using a medical CT scan.

INAZAKI Eriko

- “Euphoria”(2023) by INAZAKI Eriko; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

- “Amrita”(2023) by INAZAKI Eriko; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

- The detail of “Amrita”(2023) by INAZAKI Eriko; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

- Ms. Eriko Inazaki

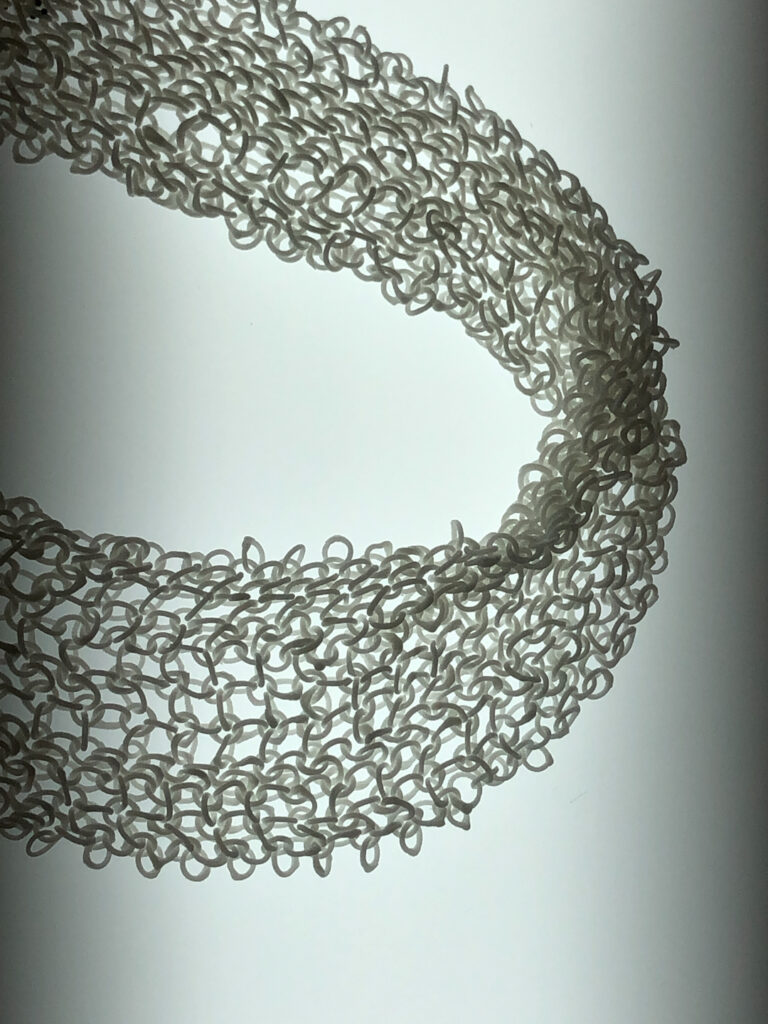

INAZAKI Eriko (1972-) (age 51) astonished me with her works “Amrita” (2023) and “Euphoria” (2023). I have never seen such a flexible ceramics which you can fold like cloth. The pieces, which are made up of more than 10,000 tiny pieces of ceramics, can be shaped like cloth or a ribbon. (See Column 1)

All of the works by contemporary artists are driven by their unique spirit of inquiry, and each of them spends a daunting amount of effort and time in creating works of transcendent technique.

“The 17 artists in the exhibition, have the spirit to do something that no one has ever done before, and are creating something amazing that anyone can see immediately. They are truly extraordinary athletes as brilliant as sports players in Olympic games such as HANYU Yuzuru ” said Mr Yamashita.

Special thanks to Ms. Maki Asakawa, the curator of ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum. This is the scene in which INAZAKI Eriko installed her work “Euphoria”(2023) at the museum.

Meiji crafts

- “Persimmons” by ANDO Ryokuzan (1885-1959); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

- “Vase with pine trees and cranes”by UNNO Shomin (1844-1915); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

- ”Maki-e lacquered incense box with feathers”by SHIRAYAMA Shosai(1853-1923); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

- “Pair of vases with butterflies and wisteria” by NAMIKAWA Yasuyuki(1845-1927); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

This exhibition also features Meiji crafts, in which you can see chozetsugiko, or transcendent technique, which astonished the world in the nineteenth century.

Some of the works in the exhibition are the cloisonne items, NAMIKAWA Yasuyuki(1845-1927)’s “Pair of vases with butterflies and wisteria ,” metalworker UNNO Shomin (1844-1915)’s “Vase with pine trees and cranes,” and SHOAMI Katsuyoshi (1832-1908)’s “Vase in the shape of a sponge gourd.” ”Maki-e lacquered incense box with feathers”by SHIRAYAMA Shosai(1853-1923) and “Persimmon” by ANDO Ryokuzan (1885-1959), who created super-realistic ivory carvings. Most of these Meiji crafts exhibited here are from the collection of the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum.

By comparing the handiwork of Meiji crafts and contemporary artists, you can experience the DNA of chozetsugiko as a transcendent technique that has been passed down to the new generation and continues to evolve.

So, what is the DNA of transcendent technique? I visited the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum to explore this concept. Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum of Art is a private art museum founded in 2000 by Mr Masayuki Murata, the director of the museum. I interviewed him to find out how he started his collection.

”Inro with sectioned patterns”by SHIRAYAMA Shosai(1853-1923); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

“About 37 years ago, when I was still an office worker and on a business trip to USA, I visited New York during the weekend, looking for the European ceramics I had collected. I saw an inro 4.Inro is a small case for carrying personal seals or medicines used when travelling and were carried suspended by cords from the sash, and netsuke, the ornamental toggles which fixed the cords at the belt. Inro was used by travelers of all classes during the Edo period. in the display window of an antique store in a building in Manhattan. My eyes were glued to it. I couldn’t believe that such a delicate and condensed world of beauty existed in this world. I couldn’t compare it to the inro I had seen in Japan. When I went inside, I was introduced to the world of Meiji crafts, I was surprised by their incredible refinement and high degree of technical accomplishment and thought that Japanese people were making amazing things during the Meiji period,” and at the same time, I learned that most of these first-class fine pieces of Meiji crafts had gone overseas.”, Mr Murata said, looking back on his fateful encounter with Meiji crafts in 1986.

Mr Murata was then an executive of Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd., founded by his father. He began buying back Meiji crafts that had been sold overseas, mainly through auctions. He retired from his job at the age of 47 and established the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum. His collection, which started with three inros, has quickly expanded and now has around 10,000 items, with nearly 900 inros.

Mr Victor Harris 5.Victor Harris, Keeper Emeritus of Japanese Antiquities of The British Museum when the book was published in 2006. He translated A Book of Five Rings written by MIYAMOTO Musashi, into English. wrote about the collection of the museum in the book published by Mr Murata, Japanese Crafts of the Late Edo and Meiji Periods – Masterpieces of Skill and Beauty (Tankosha, 2006).

”The collections of the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum consist of the finest crafts of the Edo (1600-1868)and Meiji (1868-1912) periods, which had been exported to Europe and America in the decades following the Meiji Restoration of 1868… Mr Murata, the director of the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum, has built up over the years the most significant collection of high-quality pieces to be found anywhere in the world, including the traditional and export metalwork of the sword-fittings makers, the lacquer artists, the decorative enamelled ceramic ware of the “Satsuma” type, and the unique Meiji era cloisonné of the top makers.”

Techniques such as metalwork and cloisonné were born in distant countries along the Silk Road. However, after being introduced to Japan, they evolved greatly and became established as unique techniques. In particular, lacquer maki-e techniques were specific to Japan. These techniques were often used to decorate forms such as sword scabbard, inro and incense utensils. Their technical level and expressive power reached their peak from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period. This is because excellent artists have been nurtured through the support of the shoguns, feudal lords, merchants who were rapidly gaining power, and, since the beginning of the Meiji period, the imperial family.

After the Meiji era in 1868, when the Edo shogunate was overthrown, the Sword Abolition Order (1876) was issued, Japanese lifestyles rapidly became Westernized, and tastes in art turned toward the West. Demand rapidly declined, the number of craftsmen decreased, and the technique declined. On the other hand, these works of art have received very high praise overseas, and they are said to continue to be exported to this day. Against this backdrop, Mr Murata’s accomplishments in purchasing back outstanding works and establishing Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum are significant.

Mr Kazutoshi Harada 6.Kazutoshi Harada. Special Research Chair of Tokyo National Museum when the book was published in 2006 also wrote the following text in Murata’s (2006) book:

“The highly detailed craftsmanship that evolved across a wide range of crafts in Japan, particularly during the Edo period-metalwork, lacquerware, ceramics, and wood and ivory carvings, is unrivalled elsewhere. In Japan, these craft objects were implements of daily life. It was Europeans who first recognized them as works of art and began to collect them as such.”

According to Mr Harada, “Japanese maki-e was exported to Europe at the end of the sixteenth century, probably by Portuguese or Spanish ships.” Even under the national isolation policy of the Edo period, Japanese lacquerware was exported from Nagasaki to Europe by the Dutch East Indies Company and has been known in Europe since the 17th century, Japanese lacquerware came to be called “Japan” in Europe.

Mr Harada cites French queen Marie Antoinette (1755-93) as a well-known early collector of Japanese crafts. Her collection focused on small eighteenth-century lidded boxes in naturalistic shapes, such as gourds, dogs, and domestic fowl. It also included sets of five or six nested lacquerware boxes decorated with maki-e images’ jewel was often kept in the smallest, innermost box of the set.

Meiji crafts are the legacy of the peace of the Edo period

“Vase in the shape of a sponge gourd” by SHOAMI Katsuyoshi (1832-1908); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

“During the Edo period, there was a period of peace with almost no wars for 260 years. As a result, the swords and armor of the samurai became art. The feudal lords competed with each other for the excellence of that art and urged their own metalsmiths and maki-e craftsmen to make better products than others. The townspeople, who had gained economic power, also commissioned the town’s metalsmiths and maki-e artists to make products better than the samurai. The shogunate, the authority then, occasionally issued ‘sumptuary laws’ and luxury was prohibited. But the townspeople got around them and developed a secret culture of life such as ornament or fashion, where people were modest on the outside and luxurious on the inside.” says Mr Murata.

In the Edo period, feudal lords and other samurai competed based on culture rather than military strength. This legacy became the main products exported overseas during the Meiji era.

“In the early Meiji period, traditional crafts were an area in which Japan could compete with other countries’ industries, and Japanese crafts received high praise at successive World Expositions.” (Victor Harris in Murta’s 2006 book).

Tracing the history of Japan’s participation in the World’s Expo (Expositions) in 1862, at the end of the Edo period, British diplomat Rutherford Alcock exhibited a large-scale collection of Japanese daily necessities at the Second World Exposition. The first time Japan exhibited at the World’s Expo was in Paris in 1867 (Keio 3). The approximately 100 items brought by the group received high acclaim, including weapons, armour, pottery, dyed textiles, and lacquerware.

Japan exhibited at the World Expos in quick succession, from Vienna in 1873 (Meiji 6) to Philadelphia in 1876 (Meiji 9) to Paris in 1900 (Meiji 33). The reputation of the exhibition directly led to the export of Japanese crafts and the acquisition of foreign currency, and from the beginning of the Meiji period, trends in Western tastes and countermeasures were also studied as part of national policy. The characteristics of Japanese crafts that were appreciated overseas were their fineness and sense of colour. Among the export items, there were objects of overly decorated metalwork, intricately coloured ceramics, and large plates that were strongly aimed at overseas markets. But the masterpieces also were created. In 1893 (Meiji 26), metalworker SUZUKI Chokichi’s “Twelve Hawks” was exhibited at the Chicago Exposition and received rave reviews in American newspapers.

“In the early Meiji period, there were a lot of ridiculously large-sized items and overly decorated items that Westerners liked, and I didn’t think that such items were good at all. However, in the Meiji period, with the influx of overseas culture, works with a new feel were created in Japan. For a limited period of about 40 years from 1880s, truly wonderful Meiji crafts were created. I believe that the master craftsmen of this era were well-versed in Japanese painting and possessed a high sense of aesthetics. This meant a sense of space, such as the beauty of blank space, and a dignified expressiveness, such as elegance and sophistication. However, as Japan modernized, became a military power, and developed its industries, the competitiveness of handicrafts gradually disappeared, and talented human resources flowed to shipbuilding, steel manufacturing, and military industries. The time-consuming, ultra-detailed handicrafts were lost.” says Mr Murata.

While elaborate fine crafts were becoming obsolete, Japan promoted modernization with the aim of enriching the country and strengthening its military, transforming it into a military nation in the Meiji period.

The best Meiji crafts were produced primarily for export, so they fell into the hands of wealthy and discerning collectors overseas, and with the exception of a few purchased by the Emperor and the Ministry of the Imperial Household, very little remained in Japan. As Japan’s lifestyle became more Westernized and exports to other countries shifted to industrial products, the demand and the people who supported Meiji crafts disappeared. The fine craftsmanship of Meiji crafts was not inherited and became a lost technology.

About a hundred years later, Mr Murata bought back the first-class works of Meiji crafts from overseas and displayed them as the permanent collection at the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum and in 2016, large numbers of Murata collection moved to The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. It is significant that substantial numbers of fine pieces of Meiji crafts have been exposed in the museums and in a series of popular exhibitions titled Chozetsugiko, making them known to the Japanese public.

“I’m glad that young artists today take on the challenge of fine crafts, stimulated by my collection. However, I am concerned about the fact that the word “chozetsugiko’’, transcendent technique, has taken on a life of its own and Meiji crafts tend to be labelled as the art of super technique. The focus should not be only on the technique. I don’t think it’s true that only super-realistic expressions are to be praised in lacquerware, woodcarving, metalwork etc. The heights reached by the Meiji craftsmenship are about expressions of overwhelming beauty such as elegance, sophistication, and the sense of space.” Mr Murata says.

KANEGAE: opening up the future of crafts with chozetsugiko (超絶技巧)

The contemporary artists participating in the exhibition In the Genes, Taking Marvelous Meiji Craftmanship into the Future spend an enormous amount of time and effort to create their works.

Today, modern crafts incorporate computers to improve efficiency and speed. We are now in an era where we can use AI and 3D printers to create vessels, furniture, and even buildings that look as though they were made by the hands of master craftsmen. However, the artists in this exhibition, as if going against the trend of efficiency, are sitting down, working with their hands every day, and immersing themselves in their creations like athletes. How do they make a living?

A gallerist is the key to supporting the production and livelihood of artists. Mr Hideo Kanegae, director of KANEGAE, a gallery which deals with MAEHARA, HONGO, and OTAKE, whose works are exhibited at the exhibition. speaks passionately about the individual strength of each artist.

“MAEHARA worked as a professional boxer, cook, and bartender in his 20s, and entered the oil painting department at Tokyo University of the Arts at the age of 32, graduating at the top of his class. He is a wood carver and only makes one or two pieces a year. Among the artists of KANEGAE, he is like a general leading the young artists forward. HONGO is an iron forger. I think that he is a rare talent that only appears once every two or three hundred years. After graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts, he developed the phantom technique of hammering a single iron plate into shapes in his own studio without asking anyone to teach him. However, no one understood its value and not only art dealers, but also even the artist himself was unaware of its greatness. OTAKE, a wood carver, is also a genius. His “Moonlight” is a mysterious work with the motif of a beautiful flower under the moon. When you pour water on it, the flower blooms. The blooming condition changes depending on the weather, so it looks as if it really had life. This work by OTAKE is a companion piece to HONGO’s “Visible” series, which adds the four-dimensional element of “time” to a three-dimensional object, and exposes even the invisible parts of the inside.”

Mr Kanegae has a gallery in front of the main gate of Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto, and deals with a wide variety of crafts and arts from the ancient era to the present day. This summer, he changed its previous name “Oriental Antiques Kanegae” to “ KANEGAE”.

Mr Kanegae juxtaposes old and new works in a modern traditional Japanese space designed by him and his friends from his university, at which Mr Kanegae studied architecture. Traditional folding screens, hanging scrolls, and tea bowls sit harmonized perfectly with works by contemporary artists.

“Oriental Antiques Kanegae” was started by my father and originally dealt with Jizai, or Jizai ornaments (Note 3 ) from the Edo and the Meiji periods. Jizai ornaments are Meiji crafts made with highly detailed and intricate production techniques. 90% of these works were sold overseas. Since I joined his gallery, the number of works by contemporary artists has increased. We changed the name of our gallery because we want to introduce more advanced crafts to the world.” says Mr Kanegae.

“Jizai originally gained popularity in Europe and America, but now it is widely recognized by people in the Middle East and China, as it is also exhibited at auction houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Jizai used to be an export item that earned foreign currency during the Meiji period. In the past, it was presented to the Pope, so it was also used as a gift for diplomatic purposes. ” he continues.

He started working in his father`s gallery after graduating from Kyoto University of Art and Design. “As I worked with the works of deceased artists known as Meiji Kogei,or Meiji crafts, I felt disappointed that their wonderful techniques had not been passed down to crafts of our time, and at the same time felt frustrated as I could not be involved in the process of creating works of art. While accumulating knowledge and experience as an antique art dealer, I looked for opportunities to be involved in the creative process.”

“Jizai Gengoro” by MITSUDA Haruo; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at the exhibition of KOGEI Next in Tokyo (October 20 – 22, 2023)

About 15 years ago, he saw MITSUDA Haruo’s crab, a jizai piece at the school graduation exhibition at Tokyo University of the Arts. “I was surprised to find an artist still creating jizai today. I immediately bought his works and started buying contemporary works. As an antique art dealer, I bought works by artists from the end of the Edo and the Meiji periods, I showed them to MITSUDA and this inspired him to create even better works, which brought a virtuous cycle,’’ said Kanegae.

Mr Kanegae shows fine pieces of Meiji crafts to his gallery artists and has lots of conversations with them. The artists are inspired and talk about their perspectives and techniques of Meiji crafts. Mr Kanegae talks about the ideas of space, products, and design that he learned at his art university. He gave various advice and concepts of contemporary art. This leaves a space for co-creation.

“I personally feel that contemporary art tends to have a concept but lacks technology, and crafts have technology but lack a concept. I want the best technicians to have the best concepts. I would like to create a field to fuse skillful crafts and contemporary art,” says Mr Kanegae.

Mr Kanegae supports the production and environments so that artists can show their true potential in modern times and connect with society.

“Some artists talk with me from the concept stage, others only share the first part with me and refine the rest on their own, and some don’t talk about it at all. The difference is the reflection of the individuality of the artist. I am like an editor for novelists. As I have to buy their works in advance, I cannot handle many artists and cannot hold exhibitions frequently so that I can keep a very close relationship with each artist.”

- Mr. Hideo Kanegae and Mr. Haruo Mitsuda; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at the exhibition of KOGEI Next in Tokyo (October 20 – 22, 2023)

- “Jizai Gengoro?” by MITSUDA Haruo; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at the exhibition of KOGEI Next in Tokyo (October 20 – 22, 2023)

Three years ago, Mr Kanegae and his colleagues launched “KOGEI Next,” a project aimed at the future of crafts. This is a type of art movement that connects artists who have extraordinary skills like “chozetsugiko” with companies and society, and takes on the challenge of creating works that have a social aspect unique to the present era.

“Artists and businesses meet, and they engage in multifaceted discussions and experiments, and incorporate modern thinking into the best of handicrafts. Just as in the world of sports, we evolve by providing scientific support to the creativities of craftsmen. We propose environment-friendly and sustainable crafts. By doing so, we want to leave the present era of our time in the history of art as a turning point for Japanese crafts 100 years from now.”

Mr Kanegae is also gearing up for Osaka Expo 2025. “I would like many companies and artists to be involved in KOGEI Next, and to help Neo-Japonism flourish, just as Japanese culture attracted attention at the Paris World Exposition in 1867.”

An interview with INAZAKI Eriko, Grand Prize winner of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize

Amrita”(2023) by INAZAKI Eriko; photo: Sachiko Tamashige at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum ( the exhibition of Osaka Venue: July 1 –September 3, 2023 )

The annual “LOEWE FOUNDATION CRAFT PRIZE” was established in 2016 by the LOEWE FOUNDATION. It has been decided that the 2023 Grand Prize was awarded to INAZAKI Eriko (born 1972, Japan) for Metanoia (2019).

More than 2,700 entries from 117 countries and regions were submitted to this year’s sixth annual award. Of the 30 finalists selected by the expert committee, six were Japanese, the most by any country. The artists selected have made fundamental and important contributions to modern craft, working in a variety of materials including ceramics, woodwork, textiles, leather, glass, metals, jewelry, and lacquer.

The award was judged on the basis of “works that explore techniques that take time to consider the essence of things, as well as skillful manipulation of materials. INAZAKI’s “Metanoia” is a complex ceramic sculpture that creates a crystallized surface by assembling different tiny parts. The judges commented, “This is an outstanding technique that has never been seen before, creating a synergistic effect from various elements in ceramics.’’

INAZAKI has previously exhibited works in which delicate ceramic parts are attached to the supports, including “Metanoia”, which was submitted for the LOEWE FOUNDATION CRAFT PRIZE. But in this exhibition, she shows works that have never been made by anyone before. She unveiled the first-ever ceramic work that can be folded like cloth and shaped like a ribbon. This work can be said to open up new horizons in ceramics.

“This work was a big adventure for me. My work was sometimes criticized for being overly technical. However, in my case, I believe that the expression lies in the appropriate technique. I got close to the nature of materials, trained my fingertips as if I practised playing the piano, and was able to make ceramic rings as small, precise, and beautiful as possible. More than 10,000 of them were made by going through primitive and monotonous process. I simply connected each piece together. When fired in a kiln, the size becomes 15% smaller, so I take into account the shrinkage rate, the change in the quality of the soil, and the method to create a sense of transparency before making them. I follow the nature of materials. A work is created only through an optimal process that relies on its properties, so having a high level of skill is a prerequisite,” says INAZAKI.

It was around 2010 that the question “Can I create ceramic works without the supports?” and the desire to break away from conventional objects to expand the possibilities came to her mind. However, due to a lack of skill at the time, she was unable to get started. When she participated in the second Chozetsugiko exhibition, and was stimulated by works by other contemporary artists including jizai piece. “During the coronavirus pandemic, I had more time, which allowed me to concentrate and practice, and I was able to challenge the new concept.” says INAZAKI.

“Metanoia” (2019) by INAZAKI Eriko, special thanks to the LOEWE FOUNDATION. The 2023 Grand Prize of “LOEWE FOUNDATION CRAFT PRIZE” was awarded to INAZAKI Eriko for “Metanoia” (2019).

From crafts to cutting-edge electronics industry – DNA seen in Japanese manufacturing

”Gourd-shaped vase with butterflies” by NAMIKAWA Yasuyuki (1845-1927); courtesy, Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum; photo: Yoichi Kimura

Preciseness, painstakingness, a keen eye for observation, an attitude towards handling materials, and perseverance to reach the ultimate goal. These are the characteristics seen in the Meiji era’s craftsmen, and these tendencies seem to have been inherited by contemporary artists as well.

“Perhaps meticulousness and accuracy are part of the Japanese temperament, or rather, it’s part of their DNA. I think it’s precisely because of these qualities that the electronics industry and precision machinery industry have been able to evolve to the top of the world.” said Mr Murata. He is the second son of the founder of Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd. a Kyoto-based electric component manufacturing company. He worked for the company as an executive until he was 47 years old to dedicate himself to his art mission to open the museum to show his collection. Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd., which his father founded, had a large part of the world’s share of ceramic capacitors used in mobile phones and other devices.

“The fact that I love these kinds of fine crafts and have been collecting them. It may be a result of the Japanese DNA, which continues to live in the electronics industry,’’ Mr Murata says.

It reminds me of the following words of Mr Victor Harris (note 5) when I interviewed him, the curator of Japanese antiquities at the British Museum nearly 30 years ago. When I asked him how he thought about the characteristics of Japanese people in terms of making things such as swords, metalwork, lacquerwork and ceramics. He emphasized the significance of Shintoism, or animistic cosmology, permeated in the everyday life of Japanese people and said,

“Japanese craftsmen are good at understanding all kinds of materials and extracting the essence from nature to reflect on their arts, objects and products. Since ancient time Japanese people has sensed gods and spirits everywhere in nature so that they can feel gods or spirits in natural materials such as wood and stone, as if they could listen to their voices. I think that these abilities have been passed down through generations to the present time. I think that even contemporary Japanese workers in the factories can see gods in metal parts or components on the automation line to make precise and perfect products.”

What is interesting is that both Mr Murata and Mr Yuji Yamashita, who appreciated the Meiji crafts, used to chase butterflies in the fields and mountains in their childhood.

“I liked looking at the scales of butterflies with a magnifying glass or microscope. I was really absorbed in that detailed world. Butterflies are fine crafts created by nature,” said Mr Murata. Butterflies and Meiji crafts have one thing in common: they are highly detailed and incredibly beautiful.

During the Meiji era, when fine crafts were at their peak, a world-renowned botanist named MAKINO Tomitaro was passionately active in Japan. He delved deeply into the mountains and fields of Japan, discovered many plants, recorded them accurately and meticulously down to the smallest detail, published an illustrated encyclopedia that would remain in history, and laid the foundation of Japanese botany. During the 260-year peace of the Edo period, herbalism developed under the leadership of the shogunate, and there was a huge boom in growing a wide variety of garden plants among the common people.

The Japanese people’s love for flowers and insects, composing poems praising the beauty of flowers, birds, the wind and the moon, painting them, and incorporating them into everyday items, was cultivated during the Edo period. Among the foreigners who visited Japan at the end of the Edo period, some, like Edward Sylvester Morse (1838 – 1925)7.Edward Sylvester Morse (June 18, 1838 – December 20, 1925) was an American zoologist. He came to Japan to collect specimens, worked as a hired professor at Tokyo Imperial University for two years, excavated the Omori shell midden, named the excavated pottery Jomon pottery, and created the foundations of Japanese anthropology and archeology. In between his university lectures and research, he travelled throughout Japan, leaving many sketches and collecting folk implements and ceramics. Many of them are now in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts., were fascinated by the life, everyday objects and tools of the common Japanese people. In the fine crafts of the Meiji period, the Japanese spirit probably shined at its peak as it enjoyed the maturity of its own culture, the legacy of the Edo period and was encountering the new winds from overseas. This DNA has been passed down to contemporary artists of the twenty-first century, and they are now opening up new forms of artistic expression.

Chozetsugiko, Mingei and Sodeisha

Regarding the theme of Japanese crafts, we had three significant exhibitions in the Kansai area, almost simultaneously this summer, which are the Chozetsugiko exhibition at ABENO HARUKAS Art Museum (2023. 07.01 –09.3) (touring exhibition which was featured in this article, and the present exhibition venue is Mitsui Memorial Museum in Tokyo (2023.09.12-11.26) and MINGEI: The Beauty of Everyday Things at Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka ( 2023.07.08 – 09.18) and The Sodeisha Group: An Era Born Out of Avant-garde Ceramics at The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (2023. 07.19 –09.24).

These three exhibitions show the diversity of aesthetics of Japanese crafts and each group reflects on the spirit of the time with particular social background and needs. Although Japanese aesthetics is easily associated with the simplicity of minimalism influenced by Zen and with “wabi and sabi” developed in tea ceremonies, overseas.

The culture around the tea ceremony has influenced Japanese traditional crafts but we should not forget other aspects of Japanese aesthetics developed among aristocrats such as incredibly sophisticated crafts or ordinary people’s regional folk crafts. I think that the wide range of aesthetics of Japanese crafts and arts, from austerity to luxury, made life more interesting.

Let me look at the different aesthetics of Japanese crafts through the three exhibitions in Kansai, this summer.

The Mingei movement was initiated by YANAGI Sōetsu (1889–1961) after he was deeply impressed by the beauty of the craftsmanship of an anonymous Korean ceramist (potter), although he had been writing about the Western arts such as François-Auguste-René Rodin.

The concept of Mingei(民藝), or folk craft was developed by YANAGI with a group of craftsmen such as HAMADA Shoji(1894-1978) and KAWAI Kanjiro(1890-1966) from the mid-1920s in Japan. The philosophical pillar of Mingei is “ordinary people’s crafts”. Therefore YANAGI emphasized unintentional beauty by anonymity believing that beauty was to be found in ordinary and utilitarian everyday objects made by nameless and unknown craftsmen – as opposed to higher forms of art created by named artists.

It is interesting to compare the chozetsugiko of Meiji crafts with Mingei. In the 1920s, when the Mingei movement was started in Japan, simultaneously Meiji crafts started declining.Chozetsugiko of Meiji crafts was a higher form of art created by master-class artists aiming at the high-end market for aristocrats or rich people overseas, while YANAGI appreciated the beauty of ordinary and utilitarian everyday objects, he even argued that utilitarian objects made by the common people were “beyond beauty and ugliness” as it was left to nature. Both chozetsugiko Meiji crafts and Mingei were born during the Meiji period but they show the stark contrast in terms of their focus on its beauty.

Lastly, I would like to introduce the movement of The Sodeisha (Crawling through Mud Association), the avant-garde ceramic arts group, which played a central role in Japan’s ceramics world in the post-World War II period.

The Sodeisha Group: An Era Born Out of Avant-garde Ceramics at The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (MoMAK) was the first comprehensive exhibition of this group and aims to re-examine the activities of Sodeisha through the works of its members.

The Sodeisha was formed by five ceramic artists including YAGI Kazuo, YAMADA Hikaru and SUZUKI Osamu who were each part of the production ceramics industry around Gojozaka, the centre of Kyo-yaki, Kyoto ceramics, an environment where pottery prescribed the way of life. The association had its start in searching for a new plastic art using clay by solely gazing at the post-war period. The emanation of a passionate period about to take flight on its wings toward the future prepared the way for avant-garde ceramic arts for which Sodeisha became the symbol. A brief description of the accomplishments of Sodeisha might be that, through its many active years, it caused the public to become aware of ceramics as objets and carved out a world of expression intrinsic to ceramic arts.

When I interviewed INAZAKI Eriko, whose amazing ceramic works are displayed in Chozetsugiko exhibition, she said “I made the decision to make non-functional ceramics when I was a student of Musashino Art University in Tokyo. Although, later, I joined Kyoto City University of Arts, I had such a freedom to experiment with different materials to find my own way. I did not particularly look at the history of Sodeisha group. I just focused on what I could do by exploring materials.”

I think that the legacy of the Sodeisha group is the ambience of the freedom that INAZAKI felt at the ceramic department of her university in Kyoto.

I found that something common in artists in the Chozetsugiko exhibition is that they are extremely individualistic without following their predecessors or trends. They have their own unique and strong ideas and dedicate themselves to creating a superb piece by experimenting with the materials and accomplishing their skill. The characteristic of these contemporary artists is preciseness, painstakingness, a keen eye for observation, an attitude towards understanding and handling materials, and perseverance to reach the ultimate goal, which seems to be inherited from the Meiji era’s craftsmen.

They constantly move their hands to make things by experimenting and improving their technique and are wholeheartedly immersed in creating their works. This is the key to chozetsugiko work and to open the future of crafts surviving the age of AI.

Thanks to Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum for all photos from this museum.

Venues for exhibition

The venues of the exhibition ”In the Genes, Taking Marvelous Meiji Craftmanship into the Future”.

Tokyo Venue:

The Mitsui Memorial Museum,

September 12 – November 26, 2023

Toyama Venue

The Suiboku Museum, Toyama,

December 8, 2023 – February 4, 2024

References

The Exhibition Catalogue “Excellent techniques of metal crafts, the late Edo and Meiji period”(2010) published by Sano Art Museum

Exhibition Catalogue ”In the Genes, Taking Marvelous Meiji Craftmanship into the Future”(2023) published by Asano Laboratories

Exhibition Catalogue ”Amazing Craftsmanship! From Meiji Kogei to Contemporary Art”(2017) published by Asano Laboratories

“Japanese Crafts of the Late Edo and Meiji Periods – Masterpieces of Skill and Beauty ” by Masayuki Murata (Tankosha, 2006).

Exhibition Catalogue ”KOGEI Next/ 2022”(2022) published by KANEGAE and X-tech management.

Exhibition Catalogue ”The Sodeisha Group: An Era Born Out of Avant-garde Ceramics” (2023) published by Seigensha Art Publishing, Inc.

About Sachiko Tamashige

Sachiko Tamashige studied social psychology and journalism at Waseda University, art history at Sotherbys and film anthropology at Goldsmith College in London. She worked for NHK, BBC, and Channel 4 etc. between 1990 and 2001 in London. She also wrote for newspapers such as Japan Times, newspaper weekly magazines such as AERA, monthly magazines such as Blue Prints and etc., specializing in contemporary art, architecture, design and Japanese traditional culture.

Sachiko Tamashige studied social psychology and journalism at Waseda University, art history at Sotherbys and film anthropology at Goldsmith College in London. She worked for NHK, BBC, and Channel 4 etc. between 1990 and 2001 in London. She also wrote for newspapers such as Japan Times, newspaper weekly magazines such as AERA, monthly magazines such as Blue Prints and etc., specializing in contemporary art, architecture, design and Japanese traditional culture.

References

| ↑1 | A wide variety of crafts such as cloisonné, metalwork, ivory carving, wood carving, lacquer work, and embroidered paintings were created during the late Edo and the Meiji periods, mainly for export. During the Meiji Restoration, craftsmen for sword fittings such as metalwork and lacquer artisans who used to be employed by the feudal lords and lost patronage of the samurai began to produce objects for commercial export to the West. They also encountered Western culture and created fine crafts that had never been seen before. The finest pieces made with outstanding techniques by leading master craftsmen, who were designated as “ Teishitsugigeiin(帝室技芸員,” or artists under the patronage of the imperial household, such as a cloisonne maker NAMIKAWA Yasuyuki and a metalworker UNNO Shomin, were housed in the imperial collection or leaked overseas, and the general public in Japan could hardly see them. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧)”, or “transcendent technique” “extraordinary skill”. “Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧)”, was used in the music world to accomplish marvellous technique for instruments as seen in the piano etude “Études d’exécution transcendante” (Transcendental Études) composed by Franz Liszt. It was the supervisor Mr Yuji Yamashita who gave Chozetsugiko(超絶技巧) as the Japanese title of the series of Meiji Kogei exhibitions. “Chozetsugiko” works like a catchphrase which appeal immediately the excellence of Meiji crafts which were made with extraordinary technique by the master craftsmanship of the Meiji period. Mr Yamashita, used to practice playing the koto, or a Japanese zither, passionately to accomplish “Chozetsugiko” technique to become a professional koto player when he was young. Instead, he became an eminent art historian of Japanese classic arts, He chose to use “Chozetsugiko” for the exhibition of Meiji crafts, based on the memories engraved in his body, as he himself was astonished by superb Meiji craftsmanship, the overwhelming technical ability that anyone can understand immediately. But the word “Chozetsugiko” is so appealing that it tends to be overused for different situations these days. |

| ↑3 | Jizai=Jizai-okimono, or Jizai ornament. Jizai is primarily a branch of Japanese metal crafts. They are made of metal plates such as iron, copper and silver, in the form of animal ornaments such as dragons, snakes, birds, spiny lobsters, crabs, and butterflies. It is realistic and the body segments and joints can be moved just like the real thing. Contemporary artists started making Jizai by using other materials such as wood or ceramic. |

| ↑4 | Inro is a small case for carrying personal seals or medicines used when travelling and were carried suspended by cords from the sash, and netsuke, the ornamental toggles which fixed the cords at the belt. Inro was used by travelers of all classes during the Edo period. |

| ↑5 | Victor Harris, Keeper Emeritus of Japanese Antiquities of The British Museum when the book was published in 2006. He translated A Book of Five Rings written by MIYAMOTO Musashi, into English. |

| ↑6 | Kazutoshi Harada. Special Research Chair of Tokyo National Museum when the book was published in 2006 |

| ↑7 | Edward Sylvester Morse (June 18, 1838 – December 20, 1925) was an American zoologist. He came to Japan to collect specimens, worked as a hired professor at Tokyo Imperial University for two years, excavated the Omori shell midden, named the excavated pottery Jomon pottery, and created the foundations of Japanese anthropology and archeology. In between his university lectures and research, he travelled throughout Japan, leaving many sketches and collecting folk implements and ceramics. Many of them are now in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. |