Attracted by its smell and feel, Yuliya Makliuk has taken up clay as a cause for good in the world.

I still vividly remember my first impression when I entered a pottery studio for the very first time: the smell. It was a workshop in the municipal House of Children’s and Youth Creativity in downtown Kyiv, Ukraine. At that time, I was a biology student at the university, but the dream of trying my hand at pottery had lingered for quite some time. As I pushed open the doors, I was enveloped by a warm, humid air with an earthy aroma.

Then came the touch of clay with all its moisture, seductive plasticity, and unexpected character and resistance. Little did I know that these sensations would shape my entire life.

I was introduced to the master potter, and he gave me my first lesson at the traditional kick wheel. It turned out to be an exercise in balancing the body and coordinating movements between hands and legs more than anything. I must have crafted some wonky flower pot of sorts.

Fast forward 17 years, and I’m now a full-time potter and environmental consultant. Yet, I can still vividly recall the distinct scent of drying clay, firing kilns, and probably some fine dust from that day at the Creativity House, where my clay journey began.

I love to create understated ceramics, tactile and organic. The best compliment for me is when people pick up my piece, gently stroke it, and say something like “it looks like a sea pebble” or “it feels similar to a piece of wood I recently found.” I find deep joy in connecting with nature and co-creating with it

But today, walking by the river on an unusually warm and bright late autumn day in my hometown Irpin, the questions puzzling my mind are more complex than mastering a nice pot. What does it mean to be a potter in the age of Anthropocene, when we humans have irreversibly altered the planet’s biosphere? Can we justify extracting clay, a nonrenewable natural mineral, and using fossil fuels to transform it into ceramics, just for the pleasure of creating or having a one-of-a-kind vessel? Can the global revival of interest in traditional pottery reconnect us with the Earth and nature? And finally, is ceramic craft still relevant in times of disasters and war?

Reflecting on these issues has become central to my ceramic practice over the last 1.5 years in particular, with global temperatures breaking all records and Russia initiating a full-scale war in Ukraine.

And from this thinking my ongoing project Potters Save the World was born. I wanted to connect with other artisanal potters who are conscientious about the impact of our craft, both positive and negative. Some of them harvest their own “wild” clay locally instead of buying and transporting it for long distances; others recycle industry waste to substitute natural raw materials; yet others create ceramic pieces that educate, raise awareness, and offer practical solutions to global challenges.

However inconsequential we artists may appear in the greater balance of powers, I deeply believe that those with creative minds and hands can manifest a better world. In our craft of passion, ceramics, every creation can potentially become a brick in the building of a sustainable future – or in cementing the status quo.

- Yuliya Makliuk watering Seed Sculpture

- Yuliya Makliuk, Seed Sculpture

This is what I learned on this journey:

There are two main avenues through which we potters can use our gifts for the greater good. The first is to make our making processes as sustainable as possible, ensuring that we do not harm nature and do not emit too much CO2 into the atmosphere. This reduces the environmental footprint of our craft.

The second is to create art that raises awareness or directly addresses environmental problems. This way, we increase our positive impact and become a force for change.

The first is a matter of technicality and material choices. Shifting to more “green” practices in a ceramic studio may not be as easy, as the craft is rooted in the physical properties of clay, minerals, glazes, and various firing techniques. Oftentimes, changes in these parameters mean changing the preferred aesthetics, the expression, the tradition. For example, week-long wood firings that produce a cherished wabi-sabi finish on pots, or using the deep blue ceramic colorant made from cobalt oxide picked by underpaid child miners may fall out of fashion.

Still, as more and more ceramicists become aware of the environmental and social impacts of the craft, a slow attitude shift seems to be taking place in the field. To add to this emerging discourse, I researched the carbon footprint of pottery making. I began taking notes about how much clay and glaze I was using per item, where these materials came from, and how much electricity is used for firing, and so on. Then I used specialized software to calculate CO2 emissions produced by these activities.

The results revealed that the carbon footprint of a handmade stoneware mug averaged 7.5 kg of CO2. This means that a thousand mugs equal an average human’s annual carbon footprint. This includes every stage of the mug’s life cycle, from raw material extraction to production, packaging, international shipping, use, and disposal. Firing, air shipping, and washing the mug by the owner proved to be the most significant sources of carbon emissions.

And while making ceramics is by far not as harmful to the planet as drilling in the Arctic for oil or clear-cutting the Amazon forests, craftsmen are the ones who feel deeply for the Earth and can take the lead in the green shift by adopting cleaner ways of production.

Other than that, there are endless possibilities to make clay art serve a good cause. Among ceramicists, some craft functional pieces to encourage sustainable living, others use their art to raise funds for charities, many convey powerful messages and enhance awareness through their conceptual creations, and some are dedicated to community building and trauma healing.

If I may share a few examples from my humble practice, they include ceramic travel cups with lids as a zero-waste alternative to throw-away coffee cups, the Love Earth mugs to raise funds for a National Park, Lifecycle Vases from 100% waste, and the ephemeral memorials to victims of war I Will Sprout With Flowers made from unfired clay and seeds that turned into flowerbeds as the clay degraded under the elements.

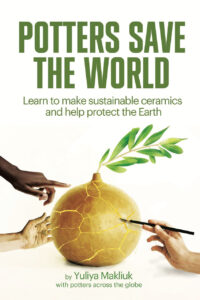

But my more significant contribution to the field, I hope, is going to be the Potters Save the World: Learn to Make Sustainable Ceramics and Help Protect the Earth book, where the stories of the most influential eco-friendly ceramicists are gathered. Their interviews are like a polylogue of ethical creators from across the globe, all sharing the idea of a more sustainable pottery and a more sustainable world.

But my more significant contribution to the field, I hope, is going to be the Potters Save the World: Learn to Make Sustainable Ceramics and Help Protect the Earth book, where the stories of the most influential eco-friendly ceramicists are gathered. Their interviews are like a polylogue of ethical creators from across the globe, all sharing the idea of a more sustainable pottery and a more sustainable world.

Can potters alone save the world? Maybe not. But can they create beautiful, responsibly made bowls that spark a conversation about nature over a shared dinner? Definitely so.

Circling back to where it started, I strive to hold a vision that in a changing world, the generations to come will still be able to smell the fresh clay from a riverbank and the warm air of a children’s and youth workshop, in peace.

About Yuliya Makliuk

Yuliya Makliuk is a ceramic artist, activist, and author driven by a passion for addressing the pressing challenges of our time: environmental crises, social injustice, and war through her practice. She is dedicated to pushing the boundaries of ceramic tradition, actively exploring sustainable approaches and innovative techniques, working from her studio Here & Now Pottery in Irpin, Ukraine. Follow @hereandnowpottery

Yuliya Makliuk is a ceramic artist, activist, and author driven by a passion for addressing the pressing challenges of our time: environmental crises, social injustice, and war through her practice. She is dedicated to pushing the boundaries of ceramic tradition, actively exploring sustainable approaches and innovative techniques, working from her studio Here & Now Pottery in Irpin, Ukraine. Follow @hereandnowpottery