Han dynasty 206 BCE – 220 CE, “Model of a house [with a dog inside the house]” early 1st century, earthenware, 20.8 x 29 x 23.8 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Lily Schloss in honour of Goldie Sternberg 2002, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

Inga Walton reviews the exhibition Dreamhome in the context of a local and global housing crisis.

The exhibition Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter (3 December, 2022-27 August, 2023) was one of the inaugural projects to be installed in the North Building at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Sydney. The project, known as Sydney Modern, is the most significant cultural development since the Sydney Opera House was opened in 1973.

Appointed to the role of Government Architect in 1890, Englishman Walter Liberty Vernon (1846-1914) was responsible for the design of the original Art Gallery with its dignified sandstone façade. Built in four stages from 1897 to 1909, Vernon’s original design for the building was not pursued thereafter. Situated on the eastern side of The Domain adjoining the Royal Botanic Gardens, the gallery was plagued by a constant need for more exhibition and storage space: three major expansion projects were completed in 1968, 1988 and 2003. Sydney Modern has almost doubled the Gallery’s exhibition space to 17,000 square metres, including utilising the moribund World War II-era Navy oil tanks in the basement.

The “strategic vision” for the project was announced in 2013, but its realisation has been both protracted and somewhat controversial. Following an international architecture competition, the Tokyo-based architectural firm SANAA was awarded the contract in 2015. The architects Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa founded SANAA in 1995, and were awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2010. The original design for Sydney Modern was revised in 2017 to a more compact, stand-alone complex of eight galleries spread over four pavilions. It is also the first public gallery to achieve a six-star Green Star design rating for ecological considerations.

Construction on Sydney Modern began in November 2019 under the supervision of regional firm Architectus, with landscaping by American designer Kathryn Gustafson. The project cost AUD$344 million, $244 of that contributed by the NSW government, and includes what is now more than $109 million in private donations raised by the AGNSW. The opening was intended to coincide with the Gallery’s 150th anniversary and the centenary of the Archibald Prize in 2021, but was impacted by bushfires, pandemic lockdowns and torrential rainfall to finally open in December, 2022.

Curated by Justin Paton, head of International Art, and Lisa Catt, curator of Contemporary International Art, Dreamhome can be viewed as a rather self-referencing affirmation. The exhibition featured the work of twenty-nine artists spread over nine spaces. Drawn primarily from the gallery’s collection, six new commissions were also presented. In Paton’s view, “these artworks are offering dreams of home but the dreams aren’t airy or fanciful. Certainly, the real-estate sense of ‘dream home’ (a palace only money can buy) is not in evidence here”. Other than standing in it? The artworks were presented in “a palace” money certainly did buy. As Paton goes on to note, “there is no better place to contemplate the meanings of home than a new and shared home for art.” Of the roughly sixty-nine works on display just over 39% could be considered craft-oriented which seemed comparatively low given that textiles, furniture, ceramics, and glass objects are all closely associated with the domestic realm and home décor.

Han dynasty 206 BCE – 220 CE, “Model of a house [with two kneeling figures inside the house]”, early 1st century, earthenware, 19.5 x 28.4 x 21.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Lily Schloss in honour of Goldie Sternberg 2002, image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

Installation view of the Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter exhibition in the new building at the Art Gallery of New South Wales featuring Michael Parekōwhai, “Te Ao Hau” (2022), glass, copper, LED lights, automotive paint on wood, fibreglass, aluminium, steel, acrylic, 237.2 x 615.1 x 318 cm. Collection of the artist (Commissioned with the support of Tony Kerridge and Micheal Do. Additional support from Michael Lett and Andrew Thomas, 2022). © Michael Parekōwhai/Michael Lett Gallery. (Installation image: Mim Stirling)

The commission “Te Ao Hau” (2022) by Māori artist Michael Parekōwhai ruminates on this concept. The two-storey sculpture, realised with the collaboration of furniture designer and craftsman Chris Nicholson, is based on the archetypal public housing in 1950s New Zealand (Aotearoa), with a weatherboard exterior. The state housing scheme, initiated in the 1930s by New Zealand’s first Labour Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage (1872-1940), was part of suite of wider policies leading up to the Social Security Act (1938). Parekōwhai was born in Porirua, north of Wellington, and lived there until he was six, an area that had the greatest concentration of state housing in the country by 1970.

Like Australia, New Zealand is enduring a significant housing crisis with some of the most expensive prices in the world, relative to income. The prevailing economic situation with inflation, escalating interest rates, and stagnant wage growth, coupled with the collapse of building firms and supply problems, has made the goal of home ownership unreachable for many. In his masterful Quarterly Essay (92) of November, 2023, “The Great Divide: Australia’s Housing Mess and How to Fix It”, leading economist Alan Kohler, AM, made the sobering pronouncement that, “the use of housing to regulate the economy is essentially a policy of cruelty.” Parekōwhai’s work expresses nostalgia for a more socially egalitarian time with more homes available to rent and at accessible price-points that people could ‘dream’ of buying.

Parekōwhai invites the audience to indulge in some harmless crytoscopophilia (the urge to look in other people’s windows), illuminating the interior with five chandeliers that resemble the starburst constellation designs by Hans Harald Rath (1904-68) for New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in 1966. Parekōwhai references the Māori meeting house known as the wharenui, which is communal and welcoming, the focal point of the marae (sacred place). Chevron patterns on the rear window shutters resemble the woven tukutuku panels that accompany ancestral carvings displayed inside a wharenui. “Te Ao Hau” (‘the world breathes’) glimmers like an unoccupied display home, and with the doors firmly shut. It is representative of the current status quo, both inviting and exclusionary, where the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ have rarely been further apart.

Installation view of the Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter exhibition in the new building at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, featuring Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan “From this place” 2022 © Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan, photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Felicity Jenkins

A proliferation of small houses, high-rise towers, tenements and ramshackle settlements made up the extraordinary and improvised cardboard metropolis “From this place” (2022) by Filipino artists Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan. The precarious canopy that greeted patrons at the entrance to the exhibition drew on the Filipino tradition of arko, coloured decorative arches erected temporarily at the entrances to towns to mark local festivals. At the time of the commission, the artists established a space within the AGNSW, “The Aquilizan Studio: Making it Home”, where patrons were encouraged to participate in hand-making these structures to be added to the overall community of cardboard. The installation was constructed from the utilitarian material because it is both democratic and ubiquitous.

A familiar sight in the lives of many people from the Philippines, particularly for the millions of diaspora working overseas, is the balikbayan box. It is a cardboard container to fill with gifts and goods to send, or bring home; in Tagalog, “balik” means “return” and “bayan” means “home country” or “community”. The artists were assisted by students from the Gallery’s Pathways program and their five adult children who help run the Fruitjuice Factory Studio. The Aquilizans work between Brisbane and the studio collective based in Los Baños in the province of Laguna. They were in the Philippines when the pandemic border closures were enacted in Australia, separating them from their family for almost three years. For the artists, the idea of home and what that constitutes became more dispiriting and acute as the international border closure extended to 21 February, 2022, an unprecedented 704 days.

The Australian population, who had effectively been under “house-arrest” and subject to various state-based public health orders including lockdowns for much of that time, had differing views of their government-mandated ‘home detention’. Feelings of vulnerability, frustration, despondency, isolation, and dejection escalated. This was particularly the case for those in greater Melbourne who endured the ‘world’s longest lockdown’ of 263 non-consecutive days at a punitive Stage 4, including travel restrictions (5km from your address) and a nightly curfew with no medical basis. The stability and security represented by the home became a more contested and insular space the longer the lockdowns wore on. For many, being confined to their residence ostensibly for 23 hours daily exacerbated mental health and domestic violence concerns, and led to feelings of Kafkaesque oppression and surveillance.

In a contrast that was both bleak and ironic, the homeless population in Australia had the opportunity to be suitably accommodated in the thousands of vacant hotels and motels across empty cities. Their usual state of displacement was ameliorated during that time and represented a rare moment of respite where they had access to food deliveries, safety and amenities. Like the Aquilizans’ installation, their housing was temporary and dependent on circumstance. The itinerant were ejected from their “covid-safe” lodgings when it suited government agencies and returned to the urban encampments that are increasingly common in many “developed” cities. Improvised hovels of cardboard for re-displaced occupants are a reality in countless suburbs as disengaged governments and over-stretched welfare agencies struggle to manage the need for crisis housing outside of pandemic mandates. Recently in Victoria the Melbourne Zero movement has posited the goal of ending homelessness and rough sleeping by 2030, but these are charity, religious, or private initiatives, no longer a policy agenda for government.

Installation view, Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter showing Samara Golden, “Guts” (2022), glass mirror, expandable spray foam, acrylic paint, dichroic vinyl, wood, fabric, plaster, paper, nail varnish, wire, vinyl floor tiles, LED strip lights, lamps, XPS foam board, latex paint, 458.4 x 732.8 x 1036.3 cm (display dimensions variable). Commissioned, 2022 (Purchased with funds provided by Andy Song and Li Ze, with the additional support of Atelier 2022). © Samara Golden. (Installation image: Felicity Jenkins © Art Gallery of New South Wales)

Compared to the utilitarian and humble cardboard of the Aquilizans, American artist Samara Golden’s installation “Guts” (2022) is one of sleek high-rise layers and deceptive surface gloss. With this project, she appears to catalyse the various meanings and associations of the word in order to assess the social ills of the global ‘body politic’, including the viscera. Paton writes that Golden, “could be described as an architect of affect- a sculptor who creates real spaces that are also headspaces, psychosocial interiors.” Spread over six levels in a mock-apartment, this disconcerting mirror world is multiplied and reflected countless times. The spaces are occupied by figures Golden calls “souls” and “transitional people”, who lie there but are not resting, as though they are trapped in a mirrored purgatory. Conceptualised when the world was stalled due to the pandemic, “Guts” hints at the divisions and injustices that period laid bare, the subsequent housing crisis, and the threat of conflict, amplified within a loop of catastrophising and doom scrolling. Like being sealed within a recurring nightmare, this home offers no respite or domestic comforts, just an infinity of disturbance, claustrophobia and unease.

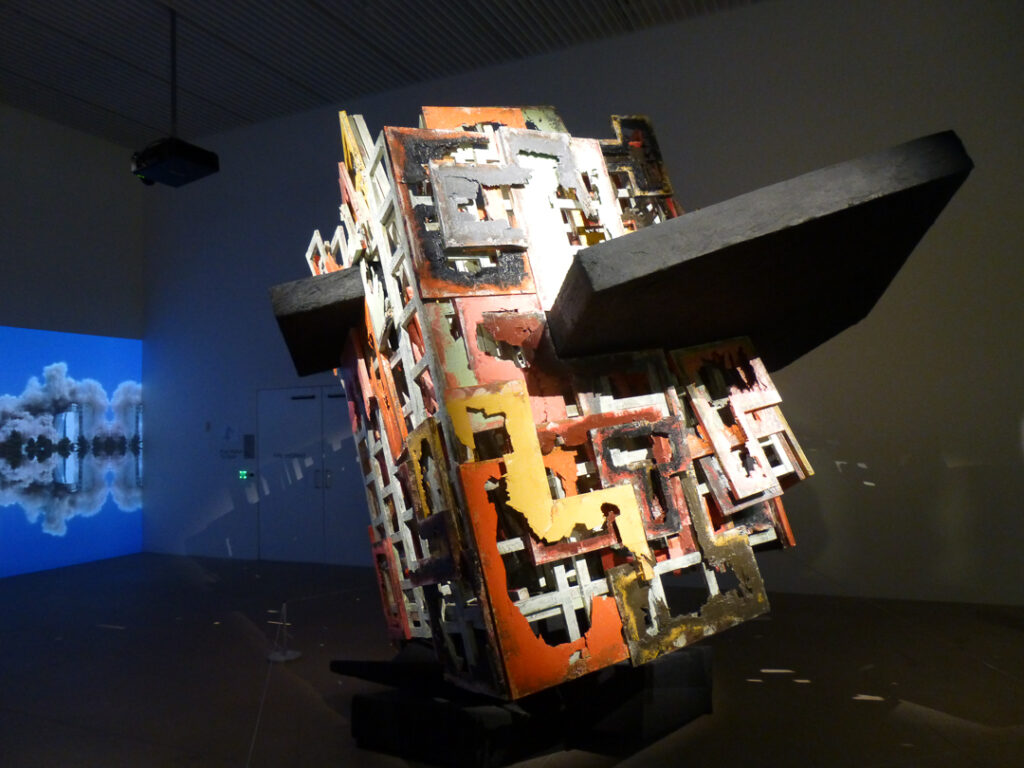

Dame Phyllida Barlow, DBE, RA (1944-2023), “untitled: brokenupturnedhouse” (2013), steel armature, polystyrene, polyfiller, papier-mâché, paint, PVA, sand, plywood, timber, varnish, 360 x 480 x 330 cm. Collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales (Gift of Geoff Ainsworth, AM and Johanna Featherstone, 2017), © Estate of Dame Phyllida Barlow. Installation image: Inga Walton

As a child raised in postwar London, Dame Phyllida Barlow (1944-2023) recalled playing in cityscapes shattered by Luftwaffe bombing raids. Upheaval, disaster and dislocation are suggested by the sculpture “Untitled: brokenupturnedhouse” (2013). Not so much a structure as a shattered cube with broken walls and cladding, two protruding black panels that might be floor slabs, and teetering on the misshapen remnants of what could be the roof cavity. This work was inspired by a radio interview Barlow heard where a man described returning to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina (2005) and how he encountered what was left of his home as a wrecked and unrecognisable form.

Barlow’s work is unnerving in that it is identifiable enough as “something” that the viewer would ordinarily scan and ignore, but now disrupts easy assessment. A house reduced to fragments of its former status due to a natural event or strategic assault is a threat to order and an affront to our idea of refuge and shelter. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, over one million people were displaced in the Gulf Coast region of America and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) received widespread criticism for failing residents. Barlow’s work acts as a reminder that not all housing can be easily replaced with a flat-pack or kit home when the site is imbued with deep trauma, exacerbated by bureaucratic incompetence.

Simone Leigh, “Sentinel” (2019), detail, bronze, raffia, 205.7 x 185.4 x 102.9 cm. Casting undertaken at Stratton Sculpture Studios, Philadelphia. Collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales (Purchased with funds provided by the Art Gallery of New South Wales Foundation, 2019). © Simone Leigh. (Installation image: Inga Walton)

American artist Simone Leigh is interested in the social histories of the African diaspora, particularly the perspective and experience of black women. “Sentinel” (2019) conflates the idea of the woman/mother in the home by presenting her as a guardian and symbol of protection- both a woman and a shelter. The figure’s Afro hairstyle and neckpiece of spreading raffia link the sculpture to the culture of North Africa and explore the connections between the physical body and the world it inhabits. The corrugated iron structure references the prefabricated Nissen and Quonset huts used in wartime and subsequently repurposed as storehouses and ready-made dwellings. However modest the space, this inscrutable figure presides over it; responsible for resources and protecting whatever it contains. She is both a symbol of safety and an active participant in enforcing it.

Installation view, Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter showing Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, Avatar Towers (2020/2022), earthenware, gold-plated bronze, bronze, acrylic, porcelain, beads, synthetic hair, digitally printed textile, hessian, polyester, custom necklaces, epoxy, crystals, automotive paint, 68 components, display dimensions variable. Collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales (Purchased with funds provided by the Mollie Douglas Bequest, with the support of Bella and Tim Church, 2021). © Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran. (Installation image: Mim Stirling © Art Gallery of New South Wales)

The title “Avatar Towers” (2020-22) has a dual meaning since an ‘avatar’ in Hinduism refers to the worldly and material incarnation of a deity or soul when they descend to Earth (the word means ‘descent’ in Sanskrit). While it alludes partly to sacred architectural structures, it also suggests a mid-rise apartment block. Sri Lankan artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran was inspired by the bamboo scaffolding of Asian megacities, and the housing complexes around the Western Sydney suburb of Auburn, where he grew up. These ‘towers’ resemble shelves in a storeroom or scaffolding platforms where multiple hybrid beings wait expectantly to engage with the audience. The fixed smiles and slightly manic bearing of some of this cohort could be read as grimaces, or expressive of anxiety, uncertainty and a desire for connection.

Nithiyendran’s works were produced during a period of pronounced social division and trauma in Australia. The pandemic period entrenched lowered public expectations, broken social contracts, state-based divisions, and created enmity about government mandates and police overreach. Communities had to form new alliances during the lockdowns in an attempt to cope with unprecedented circumstances where many vulnerable members of the community fell through the cracks. Tone-deaf government advertising campaigns like “Staying Apart Keeps Us Together” reinforced the inadequacy of these ‘social support’ measures. Nithiyendran proposed ideas of inclusion and togetherness within a makeshift society, where a sense of home is otherwise uncertain and tenuous.

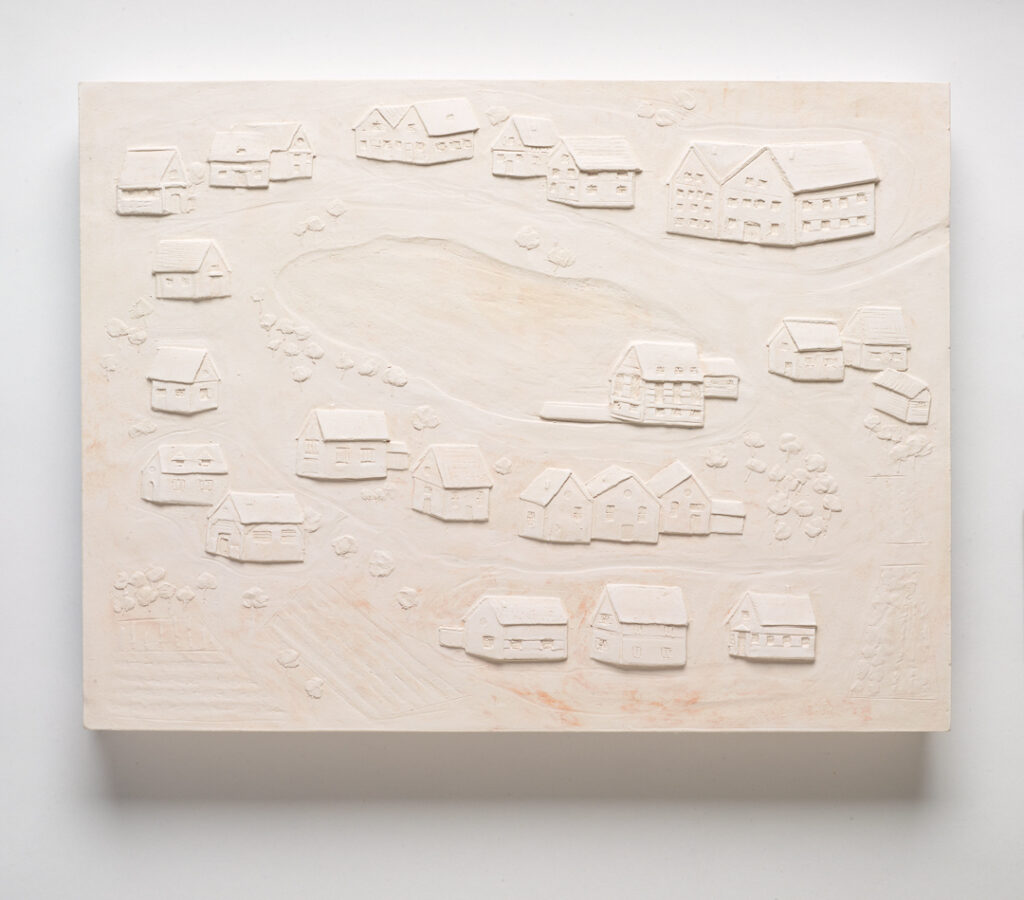

Anna-Bella Papp, “Untitled (retirement homes)” from “Plans for an unused land” 2018, clay, 40.6 x 32 x 2.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Mollie Douglas Bequest 2019 © Anna-Bella Papp, photo Jenni Carter © Art Gallery of New South Wales

For Romanian artist Anna-Bella Papp, who is based in Belgium, the point at issue is not a home, but land. Her family now has the right to reclaim ‘family land’ that smallholder farmers lost when it was collectivised by the Communist Party in 1947. Descendants can follow a lengthy and complex process to prove ownership of these plots and potentially have them returned. Papp’s paternal grandparents farmed in the north-western corner of Romania, close to the border with Hungary, in the town of Chişineu-Criş. In the series of incised white ceramic plaques/plots, “Plans for an unused land” (2018), Papp considers what might be possible if you had such an asset to use as you saw fit. She depicts various community-minded options that don’t involve building a “dream home”, ranging from buildings (artist residency, retirement homes), to the agrarian (asparagus, corn, rhubarb, or strawberry fields, a walnut nursery) in keeping with the family’s history, a sculpture park perhaps, a wind farm, or a freeway.

Jumaadi, “Boyongan (moving home)” 2019, acrylic on cotton cloth primed with rice paste, 379.5 x 312 cm, collection of the artist © Jumaadi, photo Felicity Jenkins © Art Gallery of New South Wales

Of all the works in the exhibition “Boyongan (moving house)” (2019), is referred to by curator Paton as, “most explicitly a house of dreams”. Indonesian artist Jumaadi combines painting and drawing on an expanse of Balinese cloth. This is made in the village of Kamasan in eastern Bali using a traditional method whereby cotton is prepared with rice paste, sun-dried, and carefully polished. Jumaadi is the son of a fisherman and grew up in a simple stilt house above water. On a steep hillside in the village of Imogiri, south of Yogyakarta, Jumaadi has established a studio compound where he restores antique Javanese homes. These wooden structures, damaged by time and humidity, are up-cycled and made available to the local community as a space for music and performance.

Jumaadi depicts a multi-storey floating dwelling; at once a houseboat, an escape craft, barge, or perhaps an ark or mobile archive. Within the boat is a symbolic narrative that depicts civil unrest and displacement, starting with the soldiers who quashed anti-colonial protests in 1926 in the Dutch East Indies. The figures queuing on the opposite side of the canvas represent around 1,200 Javanese who were subjugated for their dissent and exiled to the remote Boven Digul prison camp in Irian Jaya with their families. When Japanese forces invaded Indonesia in 1942 they overran the colony in less than three months. Some of these exiles were then evacuated to Cowra, NSW in 1942-43, and interned in the Prisoner of War camp with their Dutch overlords. When it was understood that the Javanese forced migrants were already political prisoners, they were released.

Incorporating elements of magic realism, Jumaadi deftly weaves this story of colonialism, culture, and Indonesian independence that reverberates in his own life travelling between Indonesia and Australia. At the bottom of the painting, long lines of workers hold the house aloft on the boat and hold the boat afloat in the ocean. This is reflected in prose Jumaadi has written that reads, in part:

We will carry him on a stretcher, this house, like a soldier shot in the leg. Past the river embankment, rocky path. We will also go through, the road in the village, entering small towns, through the market, until we arrive at the port. Where ships and boats await.And some are eternal.Those who landed and those who departed, those who were free and those who were lost, those who wept and those who prayed far and wide.Then, by boat, we cross to an island over-grown with mangroves. This house will be with us, like a wound, like a pair of legs, like longing, like the smell of the ground on the first rain, like the twilight in Surabaya.

Installation view of Dreamhome, Stories of Art and Shelter showing Igshaan Adams, “Threshold” (2019), cotton thread, cowrie shells, jasper, carnelian, glass and plastic beads, tea, 272 x 232 x 5 cm. Collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales (Purchased under the terms of the Florence Turner Blake Bequest, and with the support of Geoff Ainsworth, AM and Johanna Featherstone, 2021) © Igshaan Adams. (Installation image: Felicity Jenkins © Art Gallery of New South Wales)

Two works by South African artist Igshaan Adams reflect his childhood in the townships of the Cape Flats, many built in the 1960s, where the city’s “coloured” population were moved under the apartheid regime. His three maternal aunts taught him to weave amidst the domestic upheaval when he was taken in by his grandparents due to his father’s abusive behaviour. “Threshold” (2019) resembles the prayer mat gifted to him by a friend during a period when Adams was examining his own faith; an intricate and contemplative veil of strands embellished with a pattern of shells and beads.

“11B Larch Weg (i)” (2019) is the address of a property in Bonteheuwel not far from where Adams grew up; the home of a carer for his grandparents. Adams’ work focuses on the tapyt, a cheap patterned vinyl that lined the floors of working-class homes in his neighbourhood. Removing these aged “vinyl skins” from houses, Adams was interested in the way that the flooring was worn, and the areas that received the most foot traffic in the house. When the “map” of the property was turned into a woven representation, those areas were highlighted. They form a record of where the resident spent her time in household duties, and as part of the wider community when she sat on her veranda. The household trajectory of one woman is also constrained by social, economic and racial factors within a society governed by segregation. This political and racial imperative imposes distinct conditions and impediments on the concept of ‘home’.

Doris Salcedo, “Untitled” 2007, wood, concrete, metal and fabric, 189 x 233 x 82.5 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 2007 © Doris Salcedo, photo Jenni Carter © Art Gallery of New South Wales

The potential contents of the “dream home” seemed of less interest to curators Paton and Catt, perhaps because the potentially “loaded” nature of objects complicated the curatorial narrative. Certainly “Untitled” (2007) by Doris Salcedo, who lives and works in Bogotá, Colombia, demonstrates the way that domestic objects can bear witness to more insidious societal problems. A fairly standard wooden wardrobe is filled with concrete to express the terror and paranoia of the families of people killed or “disappeared” in the country’s decades-long civil conflicts and drug violence. Where the home and its contents should be a safe and familiar area, here the contents are stifled and blocked; no clothes laid out for coming days, clattering hangers, or small children playing in the space.

Salcedo, who has sought the testimonies of many victims and their families, conveys the fear of retribution, the suppression of normal behaviour, and the discreet desperation experienced by these traumatised individuals. The mundane aspects of life are on hiatus, as the missing person within the domestic sphere is neither publically marked nor mourned. They are beyond the reach of their families who live with the physical reminders of that loss. The person has been imprisoned or murdered by unseen forces, but the evidence of their life remains like a series of shuttered relics from a stealthy atrocity.

Installation view of the Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter exhibition in the new building at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, featuring works by Jeffrey Gibson, (l-r) “Speaking to the Trees Kissing the Ground” (2022), acrylic paint on canvas inset in custom frame, acrylic velvet, acrylic felt, glass beads, plastic beads, vintage pinback buttons, turquoise beads, abalone, artificial sinew, nylon thread, cotton canvas, nylon and cotton rope, 177.8 x 134.62 x 10.16 cm. (Purchased with funds raised from the 2023 Art Gallery of New South Wales Foundation gala dinner; and support from David Apelbaum and Werner Schmidlin; Peter Braithwaite; Michael Lao and Gary Linnane; Chrissie Jeffery and Richard Banks; Patricia Jungfer and Robert Postema; Victoria Taylor, 2023). “The Stars Are Our Ancestors (Kissing Chair)” (2022), acrylic paint on wood, bronze, Perspex, glass beads, canvas, 240 x 145 x 152.5 cm. (Purchased with funds provided by Mark Hughes, 2022). Collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales (both). The Stars Are Our Ancestors (2022), acrylic paint on canvas inset in custom frame, acrylic velvet, acrylic felt, glass beads, sea-glass beads, druzy crystal, vintage pinback buttons, vintage plastic arrowhead, seashells, abalone, artificial sinew, nylon thread, cotton canvas, nylon and cotton rope, 175.3 x 99.1 x 10.2 cm. Collection of the artist. © Jeffrey Gibson. (Installation image: Zan Wimberley).

The final space in the exhibition was occupied by an exuberant installation by Native American artist Jeffrey Gibson, “The Stars Are Our Ancestors” (2022). He created a “family room” that resembles a house museum or historical recreation, but the period Gibson depicts is somewhat more interstitial; perhaps the recent past, or sometime in the future. Made in collaboration with designer Aimee Jeffries and Sydney craftsmen Oscar Prieckearts and Kazu Quill, “The Stars Are Our Ancestors (Kissing Chair)” (2022) is Gibson’s interpretation of the nineteenth-century tête-à-tête chair, but with room for a ‘third wheel’ in the conversation. Sitting in proximity became highly fraught during the pandemic, acknowledged with the coloured glass panels built into the chairs. These allude to the millions of plastic barriers used to demarcate points of public interaction in stores and communal spaces where people resorted to shouting at each other to be heard through masks and thick panels; one of the more absurd and counter-productive aspects of pandemic ritual.

Gibson refers to wall pieces like “Speaking to the Trees Kissing the Ground” and “The Stars Are Our Ancestors” (both 2022) as “new whimsies”, portable objects that can bring a familial energy to a new and uninhabited space such as Sydney Modern. As Paton remarks, “modern art museums hardly have a reputation for fostering colour and decoration. Behind their pristine white spaces lies an assumption that austerity equates to intelligence.” Gibson provided the decoration to enliven the starkness of the gallery, inviting viewers into his futuristic parlour. “Seeing the stars as witnesses to the story of the planet and people, the universe becomes our shared space. It all becomes more intimate suddenly”, he contends.

Since it opened in 2023, Sydney Modern has been awarded the Sir John Sulman Medal for Public Architecture (2023), and the Apollo Magazine Award for Museum Opening of the Year (2023). Although the Art Gallery of NSW has achieved its “dream home”, this ostensibly “celebratory” exhibition had more troubling undertones revealing alienation, disenfranchisement, and trauma. The initial triumphalism that greeted the project has already been overtaken by long-standing budgetary problems for the institution. Maintaining the vast space and the grounds was always going to depend on significant revenue from exhibitions and events, consistent funding support from the NSW government for many decades, and continuing engagement with major sponsors and philanthropists. The final of nine commissions for Sydney Modern, “the fire is not yet lighted” by Indigenous artist Jonathan Jones remains unfinished. Conceived as a “living artwork” and intended for the public Art Garden connecting the Vernon building with Sydney Modern, it was also the most expensive project at a rumoured cost of $15 million. The commission has reportedly been the subject of several disputes about scope between Jones, other contractors, and the gallery’s executive team.

By March, 2024 the Art Gallery of NSW had a $4 million funding shortfall and signalled that it was intending to cut jobs across nine gallery departments. The NSW government announced a “top-up” payment to avert a looming $16 million fiscal hole and indicated the gallery would be subject to an audit of its finances. If Sydney Modern represented the pinnacle of a customised space to house art held in trust for the public, perhaps it has also become emblematic of overreach, unrealistic expectations, and a poor business case. Non-ticketed collection exhibitions like Dreamhome, however worthy, don’t inspire a surge of patrons to fill depleted coffers. It was not until the Louise Bourgeois exhibition opened in late November 2023 that Sydney Modern hosted a major international show. The artist’s bronze sculpture “Untitled (No. 7)” (1993) was included in Dreamhome, and while Bourgeois’ work is renowned it is not a “crowd pleaser”.

Since May 2022 the Reserve Bank of Australia has imposed thirteen consecutive interest rate rises, fuelling mortgage stress and pummelling household budgets. In his essay, Kohler asserts, “the fact that one of the three least populated countries on Earth contains the world’s second-most expensive housing is a national calamity, and a stunning failure of public policy”. Dwindling opportunity is also making the path to home ownership far harder for many of those patrons whom the Art Gallery of NSW hopes to attract, resulting in an unfortunate corollary between audience and institution. Having achieved the “dream” of a second campus, the gallery’s hierarchy seems unprepared for the obligation of greater fiscal discipline and a schedule of compelling programming needed to maintain it. This complacent attitude could be interpreted as a “too big to fail” default position. However, the failure to anticipate post-pandemic budgetary constraints suggests a lack of accountability at a time of considerable economic hardship throughout the country.

About the artists

Igshaan Adams’ site-specific installation Lynloop (Toeing the Line) (2024) (until 15 February 2025) is at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), 25 Harbor Shore Drive, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, MA 02210

Jeffrey Gibson represents the United States of America at the 60th Biennale di Venezia with The Space in Which To Place Me (until 24 November 2024) Giardini della Biennale, Sestiere Castello, 30122, Venice: His first solo exhibition at a UK museum, no simple word for time (until 4 August, 2024) is at the Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia, Norfolk Road, Norwich, UK, NR4-7TJ:

Jumaadi has a survey exhibition ayang-ayang (shadow-shadow) as part of the Tales of Land & Sea project (until 16 June 2024) at Bundanon Art Museum: 170 Riversdale Road, Illaroo, New South Wales, 2540

Simone Leigh’s work is in the group show Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend An Inch (until 4 August 2024) at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum, 20 North Main Street, Providence, Rhode Island, United States of America, RI 02903:

Curated by Frances Morris, the exhibition Phyllida Barlow.unscripted (until 5 January 2025) is at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Durslade Farm, Dropping Lane, Bruton, UK, BA10-0NL:

Samara Golden will create a new installation (28 September 2024-12 January 2025) at the Nasher Sculpture Centre, 2001 Flora Street, Dallas, Texas, TX75201:

About Inga Walton

Inga Walton is an arts writer and consultant based in Melbourne, Australia who writes widely about fine arts, fashion and textiles, film, and popular culture. Her work has appeared in over thirty Australian and international publications; she has authored numerous catalogue entries and essays and contributed to several books.

Inga Walton is an arts writer and consultant based in Melbourne, Australia who writes widely about fine arts, fashion and textiles, film, and popular culture. Her work has appeared in over thirty Australian and international publications; she has authored numerous catalogue entries and essays and contributed to several books.