Jayde Halls honours her country with a bird identified with the Bunurong men who lost their lives during colonisation.

My name is Jayde and I am a proud Bunurong woman from the Kulin Nation, living on Bindjareb Country in Halls Head, WA. It’s a beautiful place, nestled between the estuary and the ocean, surrounded by bushland and waterways. Living here has deepened my connection to Country in new ways. I would like to acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land, the Noongar people, whose knowledge and care for this Country continues to this day.

My journey with art began when I was a toddler. My Nan, who was non-Indigenous, taught me to paint. She shared techniques and nurtured my love for creativity. Sitting with her, brush in hand, learning how to mix colour and apply it to paper, are some of my most cherished memories. While she didn’t teach cultural stories, she sparked the joy of making art that has never left me.

Nature has always been at the centre of my work. I predominantly use watercolour, but over the years I’ve also worked in oils, acrylics, pyrography, and most recently, I’ve begun exploring digital art. Each medium offers a new way to express story, memory, and connection to Country. Even when I was unsure of how to voice it, the spirit of my ancestors would often find its way into my work, quietly, subtly.

Many years ago, my family held a belief, centred around a rumour, that we were of Polynesian descent. I always questioned this, as I felt a pull in another direction. There were dreams, feelings, and moments I couldn’t quite explain. About 15 years ago, after doing more research into our family line, we were finally able to put that rumour to rest and uncover the truth: we are descendants of Nancy. Our granny, Naynaygurrk (Eliza Nowen), was stolen from her Biik (Country) by colonists, along with other women and children, and displaced to Western Australia and Tasmania. This severed her connection to her land, culture, and language. She and her children were made slaves, and the process of assimilation began.

I’m often asked why I choose to identify with my Aboriginal heritage when I also have British ancestry. The truth is, I acknowledge both, yet my Bunurong ancestors speak louder. No one is forgetting how to speak English or how to make a Yorkshire pudding. What is at risk of being lost are the language, stories, and cultural knowledge of the Bunurong people. For me, there has always been a spiritual connection to Country and the old people, even when we didn’t yet have a “reason on paper” for it.

Some people hold racist and dismissive views, making assumptions about skin tone, calling it “fashionable” to identify as Aboriginal, and ignoring the deep need for connection, healing, and truth. But this isn’t new. This is who I’ve always been. I see cultural continuation as a responsibility to ensure my children know who they are, where they come from, and the language and stories of their ancestors. To keep ignoring the past, or the signs from the old ones, is to continue the genocide and ethnocide of our people, and I simply won’t do that.

Our true Indigenous heritage was hidden because in our own country, it was once more socially acceptable to be a Māori person than it was to be Aboriginal. It was also a question of safety. Children were more likely to be stolen if their true identities were known. Wages were stolen from our people, and my grandfather would not have been able to work for money had he not lied about his identity. It is heartbreaking that this led to a disconnection from culture, language, and knowledge. As I learn more about our stories, our language, and our people, I’ve been humbled and inspired. It has taken my art in a whole new direction.

Although I’ve painted for many years, I was always aware that I was raised outside of culture. My art has always carried echoes of the past, but I was cautious. I didn’t always paint what my soul wanted to; I was conscious of not appropriating stories I hadn’t yet been given. Now that I’ve reconnected, I listen more deeply to my heart. I dream on it, and paint what I see. I paint stories of my ancestors using my own style, but also using symbols we have that are specific to our mob.

I sign my art with the name Babahn Art. Babahn means “mother”, the teacher and storyteller, and reflects my role in carrying and sharing cultural knowledge through my work. I have four children and a daughter-in-law, so the name is quite literal. The name also holds a spiritual connection to Babahn Batayil, Mother Whale, who watches over us and cares for Sea Country. Just as the whale moves through saltwater songlines, Babahn Art is guided by the responsibility to nurture, teach, and carry forward stories that honour our land, our waters, and our people.

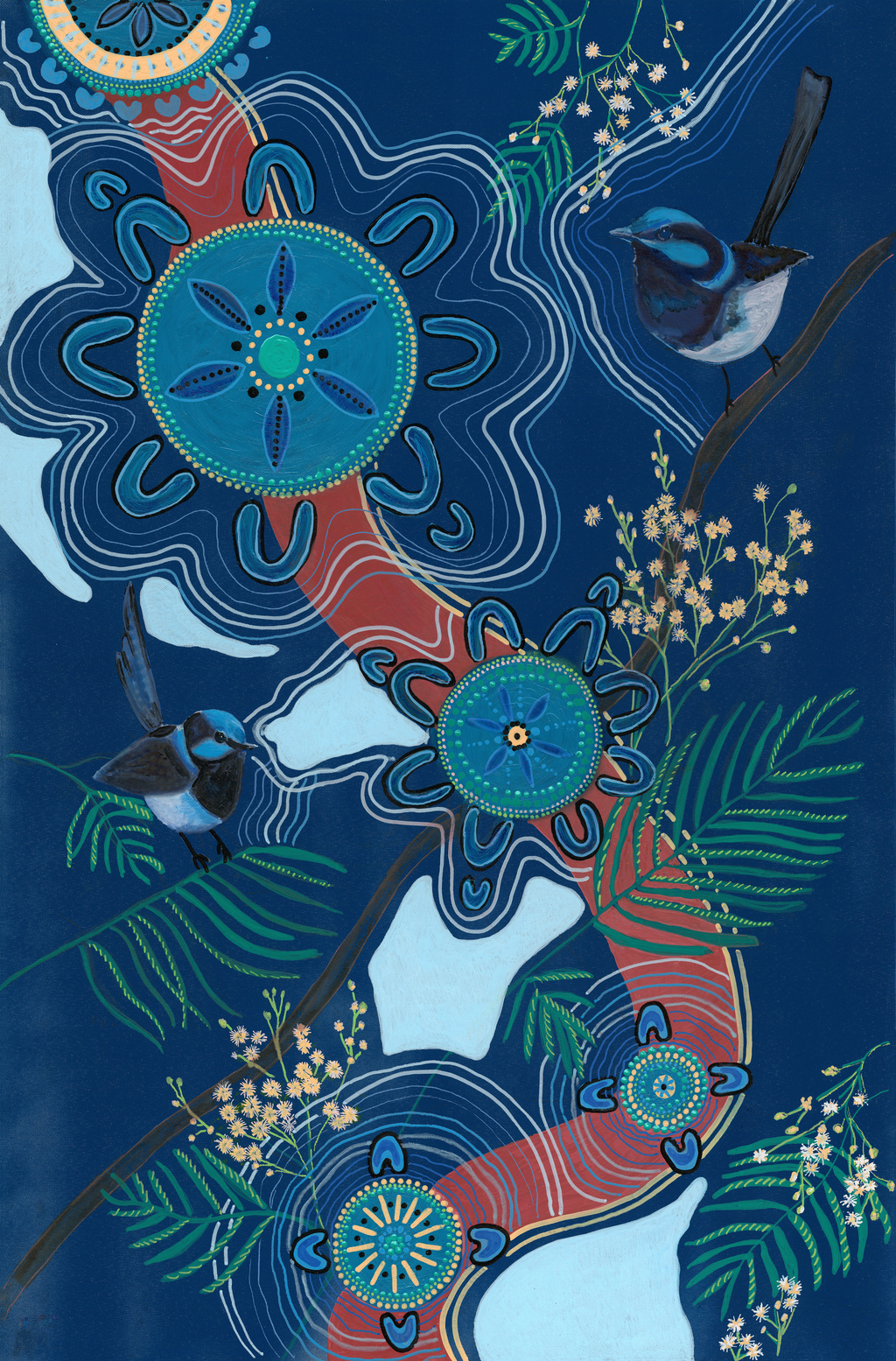

The artwork depicts the coastline of Naarrm (Melbourne), adorned with meeting places significant to the Bunurong people. These locations are not just physical spaces; they are imbued with cultural and spiritual significance. The songlines painted in the piece represent the pathways that our ancestors travelled, routes etched into the memory and soul of our people. Nature itself sang these routes, guiding our movements and connecting us to the land.

The black wattle that features in the piece was used by our people as a source of medicine, tools, food, and shelter. When the colonists arrived, they exploited the tree for the tanning industry, leading to its near extinction. There is a heartbreaking story (and several tragic accounts) that whilst Bunurong men slept, they were killed by wattle bark collectors. In my artwork, the wattle serves as a symbol of resilience and endurance. Despite the hardships and exploitation faced by our people, the black wattle endures, much like our culture and identity.

The blue fairy wrens in this piece are male, representing the men whose lives were lost for the sake of industry.

The inclusion of the blue fairy wrens is deeply significant to me. They’ve followed me around since I was a young girl. You’ve got to be careful what you say around these little, gossipy birds; they’ll tell all your secrets. In this piece, they are the witnesses. They have seen the desecration of our Country and countrymen, and they carry the secrets of the slaughter. The blue fairy wrens in this piece are male, representing the men whose lives were lost for the sake of industry.

Living on Bindjareb Country has shaped my creative journey further. The bush, the waterways, the estuary, and the ocean all offer a deep sense of connection and calm. While I’ll always belong to Bunurong Country, I’ve learnt to listen to the land here too. Country has a way of speaking, and it’s helped guide my hand and heart.

Creating this piece has been a deeply personal and cathartic experience. It has allowed me to channel my emotions and experiences into a visual narrative that honours my ancestors and acknowledges the pain and resilience of our people. This piece was chosen by the Land Council for their uniforms, which I’m incredibly proud of. But I’d love to see more Bunurong representation in Naarm. On a recent trip home, my husband and I noticed how little Bunurong-specific art was visible in places like the Koorie Heritage Trust or Clothing the Gap. We have incredibly talented artists in our community. I suspect that many are hesitant to place their work in the public eye, maybe out of fear of scrutiny, or because the stories are sacred and not always for public sharing.

Through my art, I continue to explore and express my heritage, ensuring that the stories of the Bunurong people are not forgotten. They live on, through memory, through song, through Country, and now, through paint.

About Jayde Halls

My business name is “Murrup Bulayt Designs by Jayde Halls”.