- Artist as Family (Woody with foraged mushrooms), Lake Daylesford, Dja Dja Wurrung country 2016

- Artist as Family (Meg making milk kefir), Tree Elbow Daylesford, Dja Dja Wurrung country 2016

- Artist as Family (Zero licks Patrick holding his 100% acorn sourdough loaf), Tree Elbow Daylesford, Dja Dja Wurrung country 2017

- Artist as Family (Zephyr building the Cumquat with waste materials), Tree Elbow Daylesford, Dja Dja Wurrung country 2016

Patrick Jones describes the myth, arts and ferments that both “claim” and nourish the performance collective, Artist as Family.

Creating the myth

In the creation of the world according to the ancient Greeks, Zeus, the supreme god, calls upon Prometheus, the god of foresight and memory, to distribute the essential characteristics and ecological traits to all the animals. Prometheus’s twin brother, Epimetheus, the god of hindsight and forgetting, becomes jealous and demands that he do the job. So the foolish brother hands out all that is in his basket, but forgets to save a trait for humankind. Prometheus knows that Zeus will be furious and steals fire from the god of industry and craft, Hephaestus, to give to “Man” so that “He” will no longer suffer on earth eating raw meat and being cold. Zeus discovers the theft and the botching of human creation and punishes Prometheus by chaining him to a rock where his cut-and-come-again liver is eaten out every day by an eagle. Later Heracles slays the eagle and releases Prometheus, but in the meantime Zeus has called on Hephaestus to sculpt from clay Pandora, the first woman, who Epimetheus is to marry. Pandora, in earlier tellings, is insight and comes to the union with a jar of all gifts. According to the Hesiod (c. 700 BC) version, Prometheus warns his brother not to open the jar, but Pandora opens it and all “evils, harsh pain and troublesome diseases which give men death” are unleashed upon the world. Hesiod claims: “of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble.” And thus begins the West’s linage of patriarchal narration, that regressed from pantheism to monotheism to consumerism, which still moulds the world today.

Insight to the backstory

In other cultures, in parallel, matriarchal stories, Pandora’s jar contained ferments used to praise and grieve life. By the time of Hesiod, the patriarchy of Classical Greece had reframed the story of the first mortal. Pandora became the reason humankind suffers. After letting loose pestilence, famine, disease and death from her jar, her all-giving narrative transitioned from insight through plant-sentient inebriation and preservation, to hangover and illness. The only “good” effect of her new misogynistic form was hope, it was the only thing left in the jar after all the “evils” of the world were released.

Although simply regarded as a light-hearted feeling about a perceived future, hope is often loaded down as an investment in the agency of others to put things right. This latter, more common use, is not hope at all, but expectation, and part of Pandora’s corruption. “Expectation,” writes Ivan Illich (1970), “looks forward to satisfaction from a predictable process which will produce what we [think we] have the right to claim.” Hence, predictability can only be “claimed” by increasing control of all things, by, in effect, institutionalising the cancelling out of suffering and enigma.

Pandora’s once freely organising yeasts (essential for wild fermentation) are now highly controlled and isolated strains, freeze-dried, packaged and put under economic lock and key. They are another case of autonomous, all-giving life being monetised and industrialised so we get the same flavours, the same predictable outcome. Plato’s world of serious men has become a bombardment of monocultures framed by institutionalised expectation. Fools, poets, fermentors, foragers, musicians, shamans, ratbags and other “radical homemakers” (Shannon Hayes, 2010) are left out of the forum. Only men and women trained to automate and regurgitate the imperatives of Platonic institutions can sit at the table.

Illich saw how the creation story of Pandora, her Titan husband Epimetheus and his twin brother Prometheus, is crucial in understanding our contemporary predicament as technocrats, or what I call hypertechnocivilians, caught up in an unstoppable fixing-wrecking path of city making. He writes that “[t]he history of modern man begins with the degradation of Pandora’s myth…” that “initiation by Mother Earth into mythical life was transformed into the education (paideia) of the citizen who would feel at home in [Plato’s] forum.” The forum, essentially, is the city, a place where only one species resides—Homo citizen—alongside a raft of pests that require continuous poisoning, and domesticated pets who have become like their owners, passive consumers who have their resources transported to them from places they cannot see or sense, let alone have a relationship with.

Later, Eve gets the same treatment as Pandora. The West’s two primary creation myths predate misogynistic society, but as men began to institutionalise, the stories got reworked. The general ideology shifted from an acceptance that life was unpredictable and the flow of gifts between people and the living world would ensure a close labouring relationship with such unpredictability, to one where all the “evils” of the world, which women and wild nature brought into existence, could be controlled through Platonic institutions, Promethean tools and later Pasteurian science.

The lack of connection to the creation trio of the west’s most telling myth has significant ramifications. Pandora represents insight, Prometheus foresight and his foolish brother hindsight. Our predicament as a people knowingly and actively killing off the world’s biospheres comes from the foregrounding of Prometheus and the backgrounding of Pandora and Epimetheus. This is the world in which we live today, the dominant control ideology of the West, transported and militarised into every reach, every culture. The silencing of Pandora, our shamanic brewer of cultured ferments, and the collective amnesia or disappearing of Epimetheus, our precautionary principle (the god who is there to warn us that technology, although a form of memory, is also a form of forgetting), leaves only Prometheus at the table—total mastery.

Beer, rather than hope or expectation, was what remained in the jar in the folktales of tribal Africa. The chemistry of grain or root, water and freely organising yeasts, which in turn became the shamanic ferments handed down through generations of women worldwide, were the magic gifts bestowed on humankind to aid the grieving and praising of life. For “fermentation is intimately connected,” writes Stephen Harrod Buhner (1998), “to travelling in sacred realms.” And it’s political too, he continues, “[t]he normal range of human consciousness and the behaviour that derives from it has never been so narrowly defined as in our time. This narrowing process (an attempt to provide a safety net not inherent in life itself) is becoming ever more extreme.”

In earlier cultures, women made the kefir and mead, kvass and beer. Light meads brewed by fermenting banksia flowers in water were once common in Aboriginal communities, as were gum sap ciders in Tasmania, according to Maggie Brady’s (2008) research. Indigenous and peasant women across many countries were, or fragilely remain, in alchemical relationship with the invisible, microbial wildernesses of their homes and homeplaces. To the imperialist patriarchs, fermentation was a threat to order, because it carried on a relationship with undomesticated, autonomous life. Increasingly urbanised and suffering from that which overcrowding brings, women made the malnourished and barely living alive again through their various brews. The early cities could only survive, and this is still true, on entertainment and fermented substances to help people grieve what has been lost in human culture since civil domestication. Gin, which cost nothing to make, contributed to establishing Australia, argued Robert Hughes (1986) in his The Fatal Shore. The impoverished classes (peasants who’d lost their means of economics by being kicked off the Commons) were wallowing in the English cities inebriated, hopeless and thieving to such an extent the authorities had to find more land to dump the petty-thief dispossessed, which triggered the dispossession, massacres and systematic ruination of Aboriginal economies and cultures. Entertainment and alcohol are still the primary self-medicating substances used to treat systemic depression, a step before the big pharmaceutical companies are called upon. The entertaining fool Epimetheus and the brewing shaman Pandora are today a corrupted sideshow controlled and sanitised by big money interests.

Only those children who do well at school, who learn to sit still in their seats and become well adjusted to hypertechnocivility, go on to become members of the forever marching global corporate army, barging into autonomous life, working in science, politics, international relations and business, forever working towards predictability, certainty and non-suffering. But even after such early successes in their economic ladder climb, living in well-appointed anthropocentric boxes, cars and offices, they too become depressed. There is no escaping the hollowness, the gaping holes in the ground dug out by leviathan machines to enable our extractive economy, our culture. The only treatment is relationship, an enigma that can’t be packed into a pill and on sold.

“Depression,” says Martín Prechtel (2014), “is a LACK of grief. Grief is RAGE that don’t wanna have a home.” Prechtel (1999) writes of Tzutujil initiation for young men at the time of leaving their mothers and desiring others. “Before initiation most men try to fill that young hollowness, that empty place carved by the fire flood of desire, with something that will continue the flood, trying to fill the hole with more of what made it hollow. That hollowness is Death itself, and it is in Death’s kingdom that the root of all possibility and beauty resides. Desire,” he continues after explaining how, as part of his initiation, a boy must try to steal his mother’s prime cooking pot, “is Death’s shovel, and digs the hole where one’s heart once beat.”

The stealing of the supreme tool of the mother, which is used daily to nourish the family, is so distressing for everyone that the boy will never steal again, never bring about such suffering to kin or community. But the stealing of the pot is his first dug hole of hollowness, of separating, it is his own breaking the bonds with that most loved of beings in order to become a man. However, in the Tzutujil community, he is not alone. His grief is supported by his fellow initiates, mentors and elders, and the whole village including his mother, despite her great suffering and loss.

“If a young man should attempt to fill that holy hollowness,” Prechtel continues, “with alcohol, food, women, fighting, war, ruthlessness, business, or anything else that resembles the delicious inebriating quality of that first hole dug into his life by desire and Death, then he will always be courting Death. He will probably either find his death or begin destroying things.”

Epimetheus is supposed to be the countermeasure to his brother’s powerful tools. As twins, Prometheus and Epimetheus should operate as two sides of the same coin, as technics and amnesia, masterfulness and forgetting, seriousness and foolishness. They are supposed to operate as Yin and Yang, as seemingly opposing, but complementary forces. Today, however, patriarchal imperialism, camouflaged as development or globalisation, has completely erased Epimetheus, and as a result we no longer have checks and balances or feedback loops. Instead we have the interrelated crises of climate change, trashed biospheres, aggregating urbanisation all due to resource non-accountability—not being in Epimethean relationship with the materials and tools we require for making life. We have silenced the forgetting hindsight god of our most revealing myth. He is no longer a warning, a precaution, a measure, a fool to behold and pose the question: Is this technology appropriate?

Pandora offers us ferments brewed in her jar as either delicious inebriation to enrich and praise life and be “claimed” (Martin Shaw, 2016) by our grief and the living of things. OR, and this is where Epimetheus’s absence is so revealing, as a death wish of substance abuse, always filling, forever draining her jar. The global growth economy is exactly this, forever draining the jar filled with the giving of the flowering, fruiting earth, but never involved in giving back. Instead, once empty, the jar is thrown away and a new one made so that today islands of floating plastic sludge exist, slowly breaking down, not into a life-giving brew, but a toxic soup killing all in its wake. An empty jar is unthinkable to the world’s richest one billion Homo citizens. Going without has become immoral. Our water must be mined and trucked from some far away place, refrigerated and come in plastic bottles, which are discarded after one use. As soon as we discard them it is as though they never existed. There is no relationship we can have with these vessels, no regard for the petroleum pollutants required to make them, or the oil wars that have raged for more than 100 years to keep the pipelines open for their production. It has become accepted that creeks and rivers are polluted and thus bottled water is regarded, like predictable alcohols, as a magnificent Promethean fix, and not to be challenged.

By contrast, “[o]ur elegant and strange old mentors,” writes Prechtel (1999), “not only instructed the boys how to momentarily rob their mothers [of their supreme handcrafted pot], but then, after this was accomplished, they moved on to teaching the boys how to be drunk. They taught them how to be drunk on the alcohol made from the Flowering Earth itself while longing for the love of the Goddess. In other words how to be drunk without filling the hole. In this way, one kept from becoming a drunk.”

Similarly, writes Michael Meade (1993), “if the fires that innately burn inside youths are not intentionally and lovingly added to the hearth of community, they will burn down the structures of culture, just to feel the warmth.” That is, if boys grow into men who are Promethean only, who silence Pandora and ignore Epimetheus.

How stories come forward

- Artist as Family (lunch table where all the food has a known origin point), Tree Elbow Daylesford, Dja Dja Wurrung country 2017

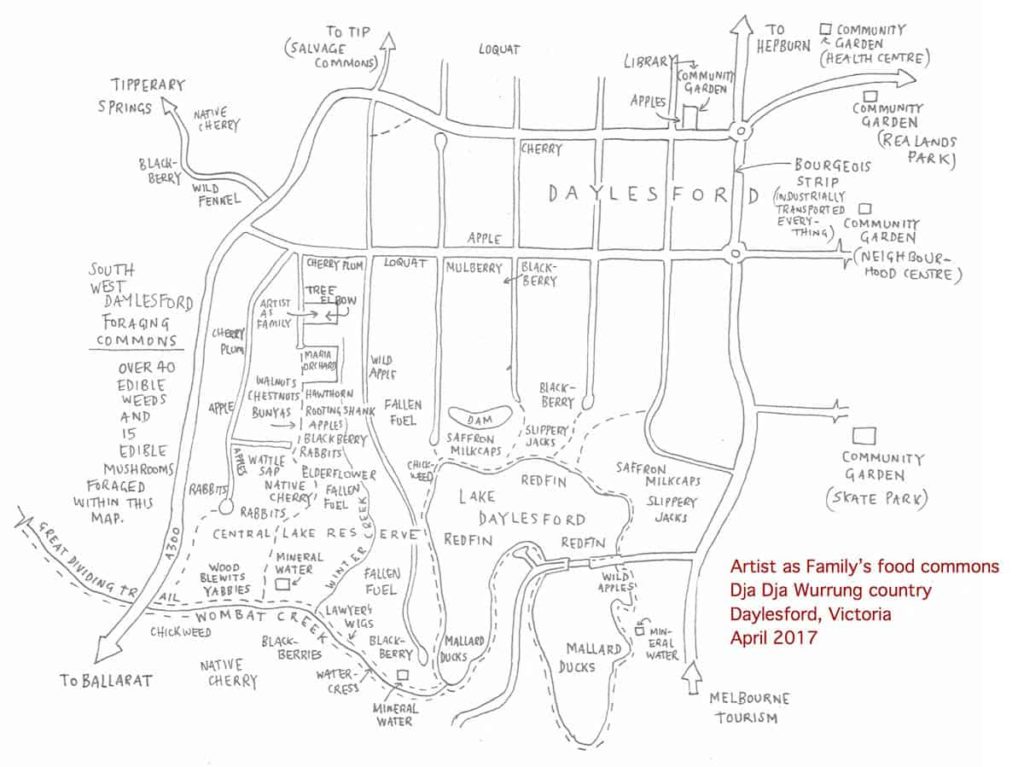

- Artist as Family (food commons map), line drawing, 2017

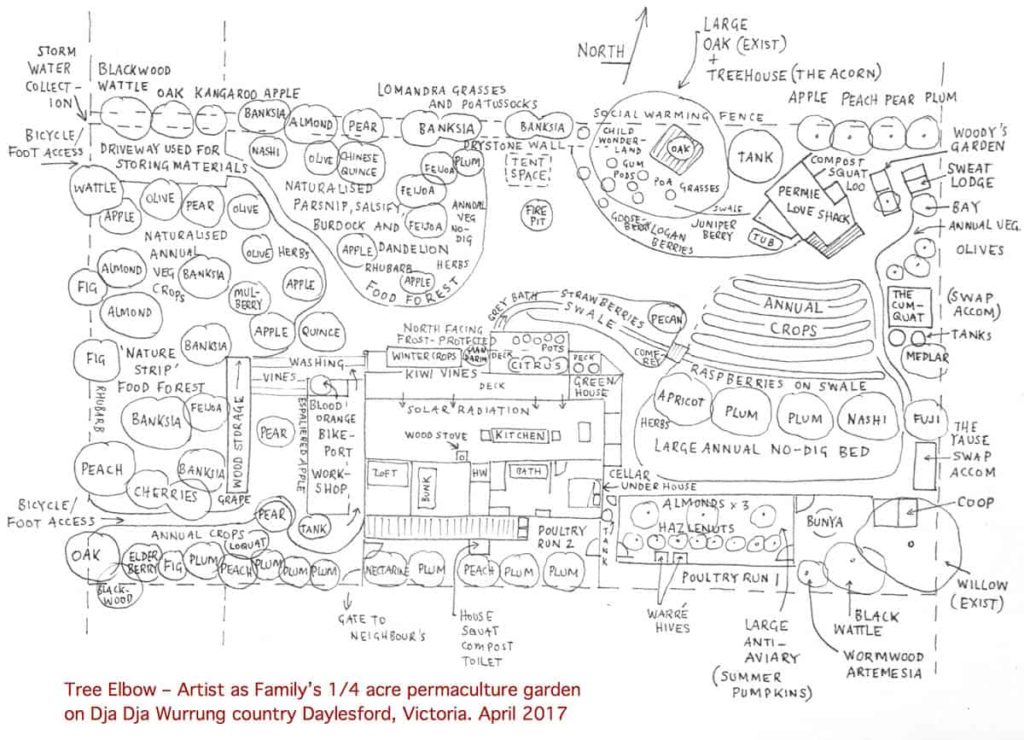

- Artist as Family (Tree Elbow home garden map), line drawing, 2017

- Artist as Family (SWAPs Connor and Marta harvesting from the garden), Tree Elbow Daylesford, Dja Dja Wurrung country 2017

The etymology for the word culture is from the Latin cultura, which means to cut, to cultivate the soil – to dig the poem, to sow the grain, to ferment the beer, to handle the living in order to make more life possible. It’s an agrarian word, which like poesis essentially means to make or produce.

In the performance practice of Artist as Family, of which I’m one of five members, fermentation is an everyday alchemical relationship with the original matriarchal Pandora. She is gut intelligence. Insight. Artist as Family has established our own forum, which we call the fermenting table and nothing whatsoever upon it is under lock and key, or is isolated. Here, there are no expectations, just relationships with the invisible, autonomous, sometimes explosive ecologies of our homeplace. Mothers or SCOBYs (symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast) reproduce autonomously and they are gifted out of the house into many others. By taking in these alive fermented foods, whose origin points we know intimately through our labours, we can now see the gut-stemming anxieties of the West—the constantly unsettled, gluten-intolerant, Crohn’s-colitis-leaky-gut pathologies of Plato, Prometheus and Pasteur, and other representatives of the West’s misogynistic, monocultural smothering of the intuitive, unpredictable, enigmatic intelligence of Pandora.

It is easy to control people with fear crusades—from household germs to global terrorism—when their economics are so abstracted away from any intimate relationship with a walked common ground. In his book Sacred Economics, Charles Eisenstein (2011) writes that “[t]he distant origins of our things, the anonymity of our relationships, and the lack of visible consequences in the production and disposal of our commodities all deny relatedness. Thus we live without the experience of sacredness. Of course, of all things that deny uniqueness and relatedness, money is foremost.” And with such denial, economic resilience is forfeited while fear and expectation are used as political tools.

In our family I make the daily beer, cider, firewater and sour breads, and bring the wood in from the forest to warm our home and keep the conditions right for the proliferation of microbial life. Meg makes the kefir milk and raw milk cheeses, cultured butter, yoghurt, kvass, meads, sauerkraut, jun, vinegars, lacto-pickles, rejuvelac and her special winter-time medicinal brew she calls “mistress tonic”. Each with their own chemistry and set of life-giving ecologies. Nothing we consume in our home is pasteurised. Very little requires money. We are neo-peasant, radical homemakers who apply ecological principles to all our labours, and this constitutes our practice of art, our culture making, and our very gendered form of feminism. In our homeplace, Prometheus, Epimetheus and Pandora co-reside in equal measure. Prometheus and Epimetheus twin as “appropriate technology”, Pandora as intuition, ecology and hope without expectation.

With four and a half year old Blackwood (Woody) as her eager apprentice, Meg passionately tends the long table set up in our little kitchen where things go-gas and glug and perform age old rituals. While Woody is a passionate advocate and student of fermented drinks, his older brother Zephyr has reached a ripening age where for the moment antibiotic-effect soft drink is more seductive to put into his gut. He finds money, works jobs for, and even steals to supply his habit of lab chemicals and refined monocultural sugars (Coca-Cola, et al.), products augmented by ad men and big dollar campaigns that target the young in a manner not too dissimilar to how child sexual predators operate: undermine the commonsense of mentors and elders, seduce with cheap treats, groom with tantalising images and prime to exploit.

For a culture of uninitiated people there are many holes that need to be filled and fires to be lit, and the people who want to grow money know this well. Zephyr’s initiation process, as it has been haphazardly curated by me and loved through many community friends, helps to counter the pervasive ad men, and Zephyr is growing up learning that despite his youthful weakness for gloss, brands, sugar and other poisoned gifts, no one can make choices on his behalf.

For Meg and I, Pandora is a goddess. She brings praise into our home and sings health forth into our living through her ferments contiguous with her and our grief. We feed her our walked-for and gardened fruits, avoiding as much as possible the rampant spread of glyphosate (another example of Prometheus without Epimetheus), and she returns us brewed gifts from the forest and gardens we tend. It is Pandora who provides for the transmission of beneficial microbes from mothers to their children at birth. She provides not just beer but all the brewed up gifts of the body and homeplace that flow in unregistered regard.

When our midwife Sally drove Meg and I to hospital, after three days of labouring at home, we were told by the obstetrician to go straight into surgery for an emergency caesar. After several hours and having once more weighed up the information presented to us, we again declined her insistence for surgery. Meg was still attempting to vaginally birth Woody. The obstetrician tried to shame us by saying we were being irresponsible, stating in her view caesar-section is the preferred method for women birthing today. Annoyed by what I perceived as Promethean intransigence, I questioned her about what I’d read on immunological succession: the transmission of the health-giving microbes from mothers to their children through the birth canal. Evidently not used to being challenged she stormed off, irritated, unable to respond to my beseeching desire to protect my child and my partner from her ideological position. We never saw her again.

But with all the hysteria of the hospital environment, it became apparent Woody was not going to birth himself. His heartbeat began showing stress, Meg’s temperature started to rise and it was then we agreed to the surgery.

When Woody was finally taken from within Meg, which was quite a procedure where we gripped each other’s hands and I smothered her forehead with my lips, our tears commingling, holding on to life together, we were relieved by two things: that Promethean science enabled a safe delivery (and a car for one day), and that Epimetheus and Pandora were there too in equal measure. Pandora, operating through Sally’s love and wild pharmacopeia knowledges and in Meg’s abundant and health-filled bodily ecologies. Epimetheus, through my reluctance to let the institution push us around, as our precautionary principle.

Woody was so deeply engaged in his birth canal, and for quite some time, that it would have been impossible for him not to have received his handed down kit of immunity microbials. If we had rushed to hospital three days earlier when we observed meconium in his waters, and given over to the fear-mongering arena of an institution that must degrade the intuition of patients despite all the mistakes, deaths and traumas made in hospitals by experts, rarely discussed, he would not have received his Pandorean gifts.

When he was born I was struck by a thick caking of substances on his crown and I knew, without science lab, medical degree or microscope, he was delivered by all three gods, and the many others who have followed our peoples in travelling succession from far and wide.

Today, Woody is a child brimming with aliveness, and our intuitive parenting knows it is because of his deep and original engagement with cultured life, with his indigenous maternal microecology, handed down, mother ancestor to mother ancestor, contiguous with the handed-down autonomous health of his home-birthed older brother, born in the small house I built with my own poet hands.

Zero, the Jack Russell wonder dog, came home with us one day as a timid, quivering little sack of skin and bones. He slept with us every night for seven months until he rose out of this attachment into the tough little man-dog he is today. This sweet, intuitive, rough-coated barker, a hunter of rats and rabbits, and more than anything, love-giver, produces some of our best medicine. His dog lick is a gift to the whole family. Dog saliva contains antimicrobials capable of killing bacteria such as Staphylococcus, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus. Animal behaviourist, Cindy Engel (2002), believes “the saliva of all mammals is an excellent disinfectant, and one type of antibody, IgA, that is particularly common in saliva is active against viruses such as polio and influenza.” All this accounts for why my unschooled, intuitive grandmother always told me to let a healthy dog lick your wounds, and why I’ve always regarded her wisdom, because a dog just wants to do it and a dog-licked wound always feels becalmed.

Our lifeway of radical biology enters and is entered by all domains. When I am with Meg, and we have had a glass of the wine that I yearly ferment with wild yeasts and the grapes that grow on the back of our public library that permaculture friends planted twenty years ago, my mouth is awash with love of both the private and intimate, and of community togetherness.

No one in our house washes very often. The boys, well, because they’re boys and we’re not pedantic parents. We adults just occasionally as we’re adamant water savers and have come to a neo-peasant realisation that it’s not necessary to wash any more than is required. Our skin’s microbiomes benefit from this. We have grown up past Alexis Wright’s (2006) analysis of the intruder, that “everyone of the white skin jumped into their showers and scrubbed themselves hard for this is what high and mighty powerful people did when they felt unclean.” We don’t have this sense of shame anymore. Meg will occasionally wash her hair with a gentle home-brewed shampoo and I will occasionally use a similar swale-safe soap, but generally water is the only substance we use. In summer we swim at the lake where we fish for redfin. In winter we will run the occasional bath or cook-out cold season toxins in our rough-cut, wood-fired sauna we’ve dubbed the Cookhouse.

It is the little places of hawthorn and ringtail drey, the secreted, grown over, left alone mushroom and rabbit places of our walked worlds that have called us home. For home is the flow of gifts between enigmatic entities –neighbours, friends, SWAPs (social warming artists and permaculturists, who come to live and learn with us), community others and the communities of the living in the near forest. Life in this emplacing forest isn’t an ideological polarisation of good and bad species. All is life, all is food, all is labour, all is relationship. Reconciliation is learning from the interrelations of old-timer and newcomer species of our homeplace, observing and interacting with their common interests and their courageous adaptation, despite their grief, which this country bares for what has been done to it by the forces of Platonic imperialism. “[T]o be of a place,” writes Martin Shaw (2016), “to labour under a related indebtedness to a stretch of earth that you have not claimed but which has claimed you,” is a more sober directive. We have intimate responsibilities to the homeplaces that have claimed us, which no bureaucrat, mortgage broker, policing authority or politician can account for, or manage. If we let go of the Promethean tools, the fixing and improving devices that as a culture we can be so smug about, then we will witness Epimetheus and Pandora returning to our lives. For Artist as Family, this has been a ten-year transition from big abstract culture to what Shaw (2016) calls “slow ground stories.” The bigness of the Prometheus-Epimetheus-Pandora creation myth has great currency and agency within the intimacy and smallness of our home and community ecologies.

Afterwords on the way to summary

Lesser known than the expulsion from the garden, the Prometheus-Epimetheus-Pandora myth remains a significant cultural mirror reflecting back to we one billion first world Dorian Grays, more or less clueless as to how the mirror got there and who framed it. “The stories we need,” writes Martin Shaw (2016) “turned up, right on time, about five thousand years ago. But they’re not simple, neat, or painless… And what’s more, they have no distinct author…” These stories have been interpreted, re-interpreted, lovingly tended as well as ideologically reframed to become our cultural memes.

In Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound (c. 430 BC), Prometheus boasts: “Yes, I caused mortals to cease foreseeing their doom.” And the Chorus retorts: “Of what sort was the cure that you found for this affliction?” Prometheus replies: “I caused blind hopes to dwell within their breasts.” Chorus: “A great benefit was this you gave to mortals.” It is worth noting that between the time of Hesiod and Aeschylus, the first stamped coins were made by the Lydians.

In the Aeschylus retelling, Pandora becomes “blind hopes,” the smothering of death, the suppression of grief, and therefore, as Prechtel (2014) suggests, the killing off of praise and the falling into numbness and depression. The controlling Western patriarchies of the past five thousand years have been forever in the business of causing blind hopes to dwell within our breasts. To protect us from suffering, to institutionalise our spirits through religion, school, sport, entertainment, drugs and alcohol so that our grief and praise for the aliveness of animate, vegetal life is buried or sanitised and our means for economic and (thus) cultural independence is forever being clipped and moulded.

From Hesiod onwards, the matriarchal mysteries associated with the chthonic realm, or underworld, became evil. According to the patriarchal institutions of Promethean technics, Platonic rationalism and Pasteurian science there is no such thing as mystery, there is no underworld, no poetics, no flowering earth, no big-bellied waning moon beheld on a drunken bicycle riding the home hills in the middle of the night tracking alongside a beseeching desire to stay in that delicious moment with the old bigness, your young, barely-hatched story attached by the pull of the light and the effort of the climb. Just ploughs and crops, labs, trucks, bitumen roads, cargo ships, packaging and the distributing of the spoils. For the distribution of resources is the great project of digi-industrial globalisation. The food that has come from the flowering, fruiting earth is transformed from precious, life-giving gift into prosaic, lifeless commodity. “Perhaps our work in the present time,” writes Gail Thomas (2009), “is to recover the Pandora image of [the] ancient matriarchal religions as a key to experiencing the chthonic psychologically, not as evil but as mystery and as cultural fermentation.”

For Artist as Family, culture is the dying process, it is fermentation—the true Pandora. It is the capturing of death in delicious inebriation, to behold or hold up for short brilliant moments grief and praise in the same intoxicating and unpredictable instance. There is no expectation here. No certainty, no holding on to the moon. Through Pandora we embrace uncertainty, we roll with her exquisite ambiguity and grace, and familiarise ourselves with her autonomous forageable foods as much as cultivate a garden. Displacement may come one day. Our resilience is our “near ground” art and craft. This is a Promethean jug, holding Pandorean brews, given to we Epimethean fools to tell and retell the grieving-praising slow ground stories of our transition away from what Deborah Bird Rose (2011) calls “man-made mass death.”

It is our intention that our boys, Zephyr and Blackwood, will leave home knowing how to turn waste into useful things, how to repair and service their means of mobility, how to build small temples of eloquence and regard, how to capture and store energy, how to grow, preserve and ferment their food, how to fish, snare, hunt and make tools for such retrieving, how to steward their local environments and share their knowledges with community friends, and those who need or ask for help.

Despite what they become, where their adult interests will lie, they’ll be prepared to adapt to whatever their future brings, to become elders not focussed on money and property, substances and polluting distractions, but on caring for the health of all the living, and keeping the gods of their intimate, walked lands nourished on the biophysical gifts of their own making, speaking with eloquence and without war, but not in sentences that roll over and with ease enable unjustness or a dwelling within blind hope.

After two decades of work, where from the vista of Epimethean hindsight I have clumsily put myself through an initiation of sorts, formed and been formed by my community where I play a role of labouring in all manners and measures, I have come to understand that culture is our daily bread, gardened fruits and forest meads, the origins of which, and our relationships to, are the forms of all that we are. For culture is the propensity to sing more life into life and to nurture the operations and ecologies that make this possible. In all our neo-peasant activities, mobilities, energies and brews that call us home to what Prechtel calls our “indigenous soul,” we can become again ecological performers of culture.

But there’s a bind here. A discomfort coming that the bourgeois strains of the dominant culture will resist.

Climate change is the return to uncertainty, a return to Pandora the goddess. Institutionalised men and men-like women will throw all the Promethean tricks, thefts and tools they can muster at such aggregating uncertainty, and cause even more rampaging to the fruitings of animate life. The simple brilliance, cleanliness and apparent innocence of a heart monitoring app on a smart phone comes with it the Epimethean backstory of mines, contamination, violent war and rape from hunting blood minerals (conflict minerals) in the Congo. No technic that springs from hypertechnocivility is innocent. As “civilisation’s absurd imperative,” writes Prechtel (2015) “goes rushing past in its never ending state of emergency,” the money (and thus the agency) of such reckless and unaccountable destruction will dry up before the last tree is standing. The central ideology of the west’s modernity, that humankind can construct certainty through institutions and defy the enigma and poetics of the flowering of animate and vegetal things, will perish into the layers of dust already regarded as the Anthropocene.

When we return to intimate homeplaces, where the animate and vegetal burrow deep into our minds with their wildness, terror and grace, and when we return to peace, for the idea that humankind is only destructive and opportunistic is another fallacy that keeps us locked inside the global wrecking ball, writings like this will seem absurd. That people actually spent their time arguing for the diverse fruitings of their small loved patch of ground where economy and culture in mutual regard congregate, will be unimaginable. What’s key to this transformation of culture is the initiation of boys into the sacred realm of the goddess of fermentation, producing nourished boys with becalmed guts who commit no violence towards womenfolk and the flowering goddesses of all the small places. With nourished guts, our boys will hear the lessons of the foolish god of forgetting, and playfully counter their delicious Promethean bravado with warrior-regard who champion the sacredness of the feminine flowering fruiting ground. Diverse cultures will flourish again, localised in story and place, and the big stories of creation will become less abstract, more grounded in intimate details and senses that allow for life to become praised in its unpredictable manners of operation. “I think it’s time,” writes Shaw (2016), “we went looking for the small gods again.”

I now sense that the flow of gifts established between such gods (the hawthorn, wood blewit, chickweed and wild apple gods, to name a few), and our neighbours, loved ones and broader community, is establishing the grounds for post-human-centric economies—sacred economies that give to the possibility of regenerating cultures that are once again sacred.

Works cited (in order of appearance)

Hesiod. The Theogony. The origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed c. 700 BC.

Illich, Ivan. Deschooling society. Harper & Row, New York 1971

Hayes, Shannon. Radical Homemakers: Reclaiming Domesticity from a Consumer Culture. Left to Write Press, Richmondville 2010

Buhner, Stephen Harrod. Sacred and Herbal Healing Beers: The Secrets of Ancient Fermentation. Siris Books, Boulder 1998

Brady, Maggie. First Taste: How Indigenous Australians Learned about Grog. Alcohol Education & Rehabilitation Foundation Ltd., Deakin 2008

Hughes, Robert. The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding, Alfred A Knopf, New York 1986

Prechtel, Martín. Grief and Praise part 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6h3JNOCTYc Emowell Project YouTube channel, 2014

Prechtel, Martín. Long Life, Honey in the Heart: A Story of Initiation and Eloquence from the Shores of a Mayan Lake. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, New York 1999

Prechtel, Martín. The Smell of Rain on Dust: Grief and Praise. North Atlantic Books, USA 2015

Meade, Michael J. Men and the Water of Life: Initiation and the Tempering of Men. Harper, San Francisco 1993

Shaw, Martin. Scatterlings: Getting Claimed in an Age of Amnesia. White Cloud Press, Ashland 2016

Eisenstein, Charles. Sacred Economics: Money, Gift & Society in the Age of Transition. Evolver Editions, North Atlantic Books USA 2011

Engel, Cindy. Wild Health: Lessons in Natural Wellness from the Animal Kingdom. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2003

Wright, Alexis. Carpentaria, Giramondo, Sydney 2006

Thomas, Gail. Healing Pandora: The Restoration of Hope and Abundance. North Atlantic Books USA 2009

Rose, Deborah Bird. Wild Dog Dreaming: Love and Extinction, Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press 2011

Author

Patrick Jones’ work is a poethical redress of the economies of homeplace; a performing of culture that is accountable to the resources and communities of life required to make it. This practice he calls permapoesis. His work surveys his familial and communal emplacing on old Dja Dja Wurrung country in central Victoria. It borrows from the economic lifeways of Aboriginal people and enacts modes of lifemaking akin to his own indigenous and peasant ancestries. Jones’ practice calls into question what is art, where does it reside, who is it for, and what communities does it belong to or stand upon? Can art, Jones’s practice investigates, be a thing lived? Can it be a resource? Can it be a homeplace; a performance of everyday ecological functioning?

Patrick Jones’ work is a poethical redress of the economies of homeplace; a performing of culture that is accountable to the resources and communities of life required to make it. This practice he calls permapoesis. His work surveys his familial and communal emplacing on old Dja Dja Wurrung country in central Victoria. It borrows from the economic lifeways of Aboriginal people and enacts modes of lifemaking akin to his own indigenous and peasant ancestries. Jones’ practice calls into question what is art, where does it reside, who is it for, and what communities does it belong to or stand upon? Can art, Jones’s practice investigates, be a thing lived? Can it be a resource? Can it be a homeplace; a performance of everyday ecological functioning?

Patrick Jones is one-fifth of the performance collective Artist as Family. In 2010 Artist as Family was commissioned to produce Food Forest, as part of the exhibition In the balance: Art for a changing world at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. In 2011 Jones was awarded runner-up in the Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize For New and Emerging Poets for his poem Step by step, which was recorded by Radio National’s Permeate series in 2012. In 2014 he was awarded a doctorate from Western Sydney University for his thesis Walking for food: reclaiming permapoesis. Also in that year Artist as Family was featured in Art & Ecology Now (Thames and Hudson). In 2015 Jones co-authored with his partner Meg Ulman the ecological travel memoir The Art of Free Travel (NewSouth), which was shortlisted for an ABIA in 2016. In that same year Jones’ practice was mentioned in Keywords for Environmental Studies (NYU Press). In 2017 his essay, “Reclaiming accountability from hypertechnocivility, to grow again the flowering earth” was published in Perma/Culture: Imagining Alternatives in an Age of Crisis (Routledge). Patrick Jones blogs @artistasfamily and @permapoesis.