The Greater Together exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, curated by Annika Kristensen, included eight artist projects that explored the nature of collaboration and cooperation as a mode of action. The exhibition was particularly innovative in opening up the “fifth wall” of the gallery. While the “fourth wall” might be considered the line dividing artist from audience, the “fifth wall” reveals the usually invisible labour that often underpins gallery work, including technicians, gallery attendants as well as the economic systems that funds the wages and infrastructure. Greater Together expanded the frame beyond audience participation to make more transparent the relations involved in its production. As well as works inside the gallery, the WORK/SHOP, developed by Laura Couttie, engaged artists to develop product for sale specifically for the exhibition.

Of particular interest is Standard Length of a Miracle by the Stockholm-based Goldin+Senneby. Over the past ten years, Simon Goldin and Jakob Senneby have explored virtual worlds, offshore companies, withdrawal strategies, outsourcing and subversive speculation. Recently their project Zero Magic recreated short selling practices in a hedge fund as a performance involving a professional magician.

Goldin+Senneby’s work for Greater Together opened up the social relations of the “art world”. Standard Length of a Miracle consisted of a real full-scale mature oak tree that was erected inside the gallery space, with branches pressing against the walls. To accompany this, they commissioned a short story from Johan Hassan Khemiri about a drycleaner who dreams of becoming an artist, changes his name to a more Swedish “Anders Reutersward”, but after several failed attempts tries to get a job as a gallery attendant. The concept issues from the artist’s long-standing fascination with the surrealist philosopher George Bataille’s secret society, Acéphale, that met under an oak tree in 1936, and their interest in the parallels of the “mysterious” machinations of contemporary capital finance. The story is read by one of the real gallery attendants at 2:12pm each day. Goldin+Senneby commissioned local fashion designer Annie Wu to create uniforms for the attendants (and other gallery staff) made entirely from clothes left behind in dry cleaners.

The gallery also commissioned two artists who work with wood to make objects out of the tree for the duration of the exhibition. Jessica Hutchison and Alex Jack had studied sculpture at VCA before collaborating on a number of projects together. Rather than use their own names, they adopted the moniker “Simon&Jacob” from the Christian names of the Swedish artists. This made overt the nature of the commission as a form of outsourcing.

Certainly, it’s not every day that you see objects being crafted inside a contemporary art space. In hi-viz vests, Alex Jack and Jessica Hutchison articulated their works for Garland while moving between the oak branches they were carving and the children under their care.

✿ How did you get involved in this project, what was the selection process and terms of your engagement?

The gallery was looking, on behalf of Goldin+Senneby, to engage two “female identifying” woodworkers to work self-directed in the gallery for the duration of the show to make crude furniture and other “use-value” objects (with little more than a chainsaw) from the severed limbs with the aim of forming a “meeting place” beneath the tree.

The gallery said that Goldin+Senneby were particularly looking for non-male woodworkers, and ideally woodworkers that would be interested in working together, so as to extend the idea of the exhibition and their own collaboration. It was communicated to us that their preference to work with non-male woodworkers stemmed from their interest in working with people who may have an understanding of being a minority in society (as is the case for the character in the text, who describes the experience of being a migrant in a largely white Swedish community). They are also, as artists, interested in being, in their words, “an equal opportunities employer”.

For Goldin+Senneby, the tree represents sovereignty, and its wood is capital. As we form part of a process of the conversion of sovereign equity into objects of value, it was necessary, despite the obvious logistical challenges, that we make the furniture in the gallery in view of the audience—we are Labour-manifest.

✿ What has been your approach in responding to the brief?

As arts-workers performing labour-manifest within Goldin+Senneby’s economy, we too are interested in the dynamics of power relations: the accessibility of contemporary art—access to opportunity in cultural work and the speculative investments that artists make. More broadly, it has led us to contemplate how we are, by virtue of our participation in this work, implicated in the enduring struggle between labour and capital.

Standard Length of a Miracle is rich with interconnecting themes. There are stories within stories, some overt and some coded, and seemingly dispirit narratives that if followed, interconnect and overlap. It’s like an inexhaustible labyrinthine puzzle, with many “ah-ha” moments to be discovered if you have the time and inclination to follow the trails. Their practice is equal parts brilliant and infuriating in its complexity, because to be implicated, to be an element of the work, necessitates that you examine your relationship to the multitude of co-existing elements. As such it led us into areas of inquiry that our respective practices may not have taken us otherwise.

Unlike the other elements that are appropriated or commissioned independently and then brought into proximity by the artists composition (i.e. the clothing or the story), our contribution unfolds over time, and in the presence of the work, an audience and in the context of the curatorial concerns of Greater Together – collaboration, the value of work, and how best to work together in the face of the financial and environmental crisis.

While commissioning arrangements tend to be tacit, economics is central to delegated performance. And while artists generally deploy outsourcing as means to increase unpredictability, in a broader context, outsourcing is essentially a loophole that allows multinational companies to absolve themselves of legal responsibility of unregulated and exploitative labour conditions. So, the question is: how does Goldin+Senneby’s practice of “deferred responsibility” through “acts of withdrawal” and outsourcing replicate the exploitative practices of multinational companies? And what are the implications for the host institution acting as “employer” in commissioning cultural workers?

After paying the arborist, riggers, install crew and management their waged labour entitlements, the institutions “not for profit” budget could only stretch to a combined fee for two people of $1200 for the woodworking component of Standard Length of a Miracle, with a minimum of 6 days in the gallery to execute the task. As is so often the case for our woefully underfunded cultural institutions, it was necessary to compensate with cultural capital by association and named acknowledgements as “equal collaborators”. This form of speculative investment on behalf of artists is what drives down our capacity to be fairly remunerated, which in turn limits such opportunities to those who are in a position, financially, to make that investment, resulting in the problem of only the voices and perspectives of those more fortunate, being represented in the cultural sphere.

This line of enquiry is in step with the broader curatorial premise of Greater Together. To paraphrase Ben Eltham at ACCA’s All Conference event, Artist’s Labour and the Speculation Economy: “cultural labour is engaged in a kind of tournament within a supply and demand economy which drives down wages. It’s ‘winner takes all’ in an increasingly unequal society”.

✿ So why did you say ‘yes’?

We undertook this project not for financial remuneration, nor for a speculative exchange of cultural capital. We undertook this project because it was an opportunity to work together. With studio space becoming increasingly less affordable and the significant costs of hiring exhibition space and promoting a show, this was an opportunity to work collaboratively in response to an important and useful curatorial premise. For us it was the opportunity to access meaningful work— that was the payoff.

Seeing as “if we wouldn’t, someone else (probably) would”, we decided to take the opportunity to explore our ontological motivation for work. A motivation that goes beyond the “rational” economy of contractual labour exchange—a self-actualising variant of work that artists are compelled to undertake, irrespective of financial remuneration. And subsequently, the implications of artist’s seemingly inexhaustible willingness to contribute vast quantities of what amounts to in-kind capital within the inherently exploitative neoliberal “stretch and extract” climate of financialisation that permeates our cultural institutions, and increasingly, our personal lives.

This perplexing tendency of artists over-giving is described by Johan Hassan Khemiri in the story central to this work, Standard Length of a Miracle:

…whether the glass is half empty or half full I am at the ready with a carafe, I pour and pour until the glass overflows, no one will leave the room thirsty when I’m around, and when I say water I mean water in the metaphorical sense, water as a symbol of my torrents of creativity and my infinite stubbornness […] if you ever end up with nothing in the gallery you can use my art, you don’t even have to pay me, my pieces would be perfect here…

Or perhaps there are answers to be found with the thinking of George Bataille who refers to The Accursed Share, the part of an economy’s wealth that cannot be recuperated and must be squandered on art. He speaks of a “general economy” whereby the expenditure or consumption of wealth, rather than its production can be the primary object:

We accumulate wealth in the prospect of a continual expansion, but in societies different from ours the prevalent principle was the contrary one of wasting or losing wealth, of giving or destroying it. Accumulated wealth has nothing but a subordinate value, but wealth that is wasted or destroyed has, to the eyes of those who waste it, or destroy it, a sovereign value: it serves nothing ulterior; only this wastage itself or this fascinating destruction. Its present sense: its wastage, or the gift that one makes of it, is its final reason for being, and it is due to this that its sense is not able to be put off, and must be in the instant. But it is consumed in that instant. This can be magnificent, those who know how to appreciate consumption are dazzled, but nothing remains of it.

However, under neoliberal capitalism, this instinctive consignment of labour that artists issue forth in the production of culture is getting us into trouble. In not conforming to a traditional capitalist labour relation to capital, we have inadvertently become the perfect neoliberal workforce: flexible, competitive, willing to work for nothing and a little bit hungry.

✿ What are you working on in the space? What are your plans for the wood?

In the spirit of collaboration and as an extension to the muddled notions of authorship, we work under the moniker Simon&Jacob and relinquish our individual named identities. Clothed in hi-vis utilitarian work-wear that contrast the sheer fabrics and bespoke tailoring worn by the institution’s staff, we reference class-based power relations and infer solidarity with the proletariat. We are a union for collaboration.

In an extension of the narrative of tearing down a symbol of sovereignty (the tree) and using its assets to create a meeting place, we assume that citizens might utilise this space to contemplate how to re-organize a society and its capital. Through functionality, text and metaphor, these furniture objects will serve to facilitate some form of reorganisation. A forum to confer on ideas such as equity, trade, difference, individualism, inequality, class and ideology by way of kinaesthetic interaction.

The arrangement of the furniture will be in response to how we witnessed the audience engaging with the work—an intimate space conducive to listening to Jonas Hassen Khemiri’ story as it is read aloud.

These are some of the furniture objects that are in the process of being made:

Considering the notion that the financial crisis is, in fact, “a crisis of imagination”, No Alternative bench suggests that its unequal-ness is innate. Not so far away, however, is an Alternative step: a block of wood that fits under its short legs to make it equal, It can be reconfigured by those that need a seat so that quite a number of people can sit comfortably.

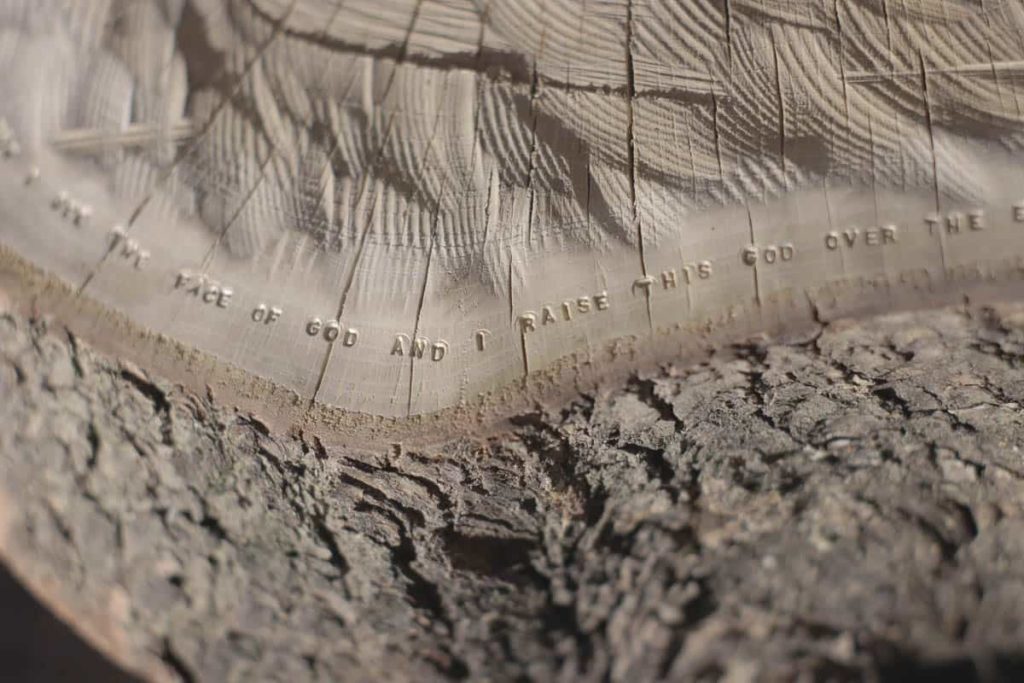

Referring to Goldin+Senneby’s interest in magic, Rand and ‘I’ (The Hovering Step of Financial Instability) appears to float just above the ground. Inscribed in very small text is an Ayn Rand quote that speaks of the origins of individualism and its ideology.

I am done with the monster of “We,” the word of serfdom, of plunder, of misery, falsehood and shame. And now I see the face of god, and I raise this god over the earth, this god whom men have sought since men came into being, this god who will grant them joy and peace and pride. This god, this one word: “I.”

The step has a smooth ball carved into the centre of the base that it balances on and can be stood upon by one person who has to continuously shift their weight to keep a level footing and maintain stability. Sometimes the gallery attendants read the story from it. When they do, it forms an embodiment of their experience of the precarious nature of casual work.

Capital finance trades on difference and inequality. Trade Out the Differential is a seesaw bench that necessitates collaboration. For it to accommodate two or more people, it requires the users to cooperate by positioning themselves so as to trade out their weight differences and sit comfortably. Through co-operation they both benefit and become untradeable.

Horizontalidad left and right refers to horizontalism as a means of organising society. Universally inclusive, it has a rhizome-like structure it can be accessed and participated in, with any degree of understanding.

Referring to the rallying cry of groups across Europe and South America opposing globalized capitalism: “Ya basta!” or “Enough is enough”. The anti-neoliberal social movement motto is exemplary of its popularity and ability to rally diverse ideologies under a common goal. In this climate of income inequality, where eight of the world’s richest individuals have amassed wealth equal to that of half of the world’s poorest, the notion of what constitutes “enough” is an idea worth thinking about.

In the quintessence of Standard Length of a Miracle, let us end at the beginning:

Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.” Milton Friedman

Artists

Alex Jack and Jessica Hutchison both studied sculpture at the VCA. They collaborated on a number of projects including A Common Thread (1998) Housework, Dance House (2006) Owner/Occupier, PB Gallery (2005) Lost and Found, Cardinia Public Art Commission (2006). Alex then went on to study Art in Public Space at RMIT, creating work in Melbourne laneways and inner northern public spaces, often collaborating with communities such as Collingwood Housing tenants and Ozanam House tenants to generate these works. Jessica has over the years extended her practice to include photography, video art, site-specific installation and film. Last year she exhibited Common at Counihan Gallery and her short documentaries including I Look at Diamonds for a Living (4min), No Measure of Health (9min) and Hell is Other People (20min) have won awards and screened at festivals such as Clermont-Ferrand in France and others.

Alex Jack and Jessica Hutchison both studied sculpture at the VCA. They collaborated on a number of projects including A Common Thread (1998) Housework, Dance House (2006) Owner/Occupier, PB Gallery (2005) Lost and Found, Cardinia Public Art Commission (2006). Alex then went on to study Art in Public Space at RMIT, creating work in Melbourne laneways and inner northern public spaces, often collaborating with communities such as Collingwood Housing tenants and Ozanam House tenants to generate these works. Jessica has over the years extended her practice to include photography, video art, site-specific installation and film. Last year she exhibited Common at Counihan Gallery and her short documentaries including I Look at Diamonds for a Living (4min), No Measure of Health (9min) and Hell is Other People (20min) have won awards and screened at festivals such as Clermont-Ferrand in France and others.