Helen Wyatt is a Sydney artist who first began making jewellery while studying Fine Arts at the University of Sydney in the 1970s. Mark Stiles spoke to her on the eve of her latest exhibition, Thresholds, at Studio 2017 Project Space, North Sydney. Thresholds was a joint exhibition with Brisbane based artist Paola Raggo. While based in Sydney part of the time, Helen is also currently a Masters research student at Griffith University’s Queensland College of Art in Brisbane.

How did the idea for Thresholds come about?

For me, I had done a show called Watermarks last year, based on the mangrove stands along the Brisbane River. I was interested in the mangroves as sculptural forms with their wonderful aerial root systems but the more I learned about their ecology the more interested I became. They have a huge role to play as fish nurseries, water and soil purifiers and so much more. Mangroves in cities are often found when an area has been taken over by industry. They become edgelands collecting debris and are often despised. In Brisbane, as elsewhere, the local council has tried to reinvigorate them and that interested me too. What I got from this was the idea of mangrove stands as liminal zones where land and water meet, but also nature and industry, and how these trees reveal tensions in the evolution of place. That stimulated my interest in history as well.

This is not the first time you’ve made work inspired by a time and place, is it?

No, I’d actually done an earlier show called Ruby Street, based on a street in Marrickville near Airspace Gallery and SquarePeg studios where I had participated in their Drawing through Journey project. I looked at the retaining wall along the middle of the street, noticed all the plant growth on the wall, and thought about this as a subject for some work, but when I investigated the kinds of plants a whole history began to emerge—traces of native habitation like tree ferns grew from cracks; date palms that had been planted in the Depression as a job creation scheme had reproduced in one part of the wall; struggling olive trees reflecting Mediterranean migration similarly sprouted in another part. The wall itself was marked by services, paint and engravings. I realized it told a story and so I tried to make pieces that, in turn, told the story of Marrickville itself.

Which brings us to the subject of narrative jewellery…

Yes. It’s not an approach that necessarily privileges beauty and simplicity but it’s a very productive one. What I make are small relief sculptures really, art that you can wear, that invites you to look at things in ways you haven’t before and makes you want to know more about what’s being referenced. But because people make their own connections and tend to make up their own stories based on these pieces there’s an interesting tension there.

The idea of narrative does open doors, doesn’t it?

Yes, because there’s another tension as well. All story telling implies sequence and completeness, but this isn’t always true in art. There may be sequence but there is no standard conventional narrative structure – it’s not usually time-based unless you are incorporating time-based media like video. My pieces imply stories rather than tell them. For contemporary jewellery artists like me, who came of age artistically in the nineteen seventies and eighties, we experienced a time of great openness about what you could and couldn’t do, and I’ve benefitted from that. I was drawn to the idea that jewellery is art that you can wear, and art that makes you think – the magazine Art Jewellery Forum consciously advocates that approach.

What else have you taken from that period in your practice?

The openness to thinking and subject matter comes first, but there was a liberating and subversive thing about rejecting preciousness as well, by using ordinary materials and so on, as Susan Cohn documents in her academic research. In those ways I’m quite conservative now; other people are much more experimental but I do believe I am conceptually experimental. At this point I’m tied to traditional metalsmithing—I might make a piece inspired by rat bones I found under my house but the skeletal remains will be reproduced in gold, silver or brass. My adult son who lives overseas proudly wears them as they remind him of home!

What about the other issues that appeared at that time, like the environment and conservation for example?

Well, I wish climate change was at the forefront of all people’s thinking now, but like most of my art jewellery colleagues, I do try to make work that is produced in an ethical and sustainable way. I’m very conscious of the environmental costs of mining for precious and base metals as well as for precious stones.

How do you get around this?

Like most practitioners, I use recycled silver and I collect my waste materials. I try to use the most benign chemicals I know of for soldering; I get the etching chemicals I need second-hand from a friend who’s an etcher, and I dispose of them afterwards in a responsible way. I haven’t gone as far yet as the artists who explicitly use rubbish in their work, like the plastic netting collected from fruit and vegetable packaging (I have a great brooch made by Majella Beck who did just this), although recently I’ve begun to experiment with recycled timber.

Just going back to history now, you’ve been thinking a lot about industrial history…

Yes, that’s the background to the Thresholds show, which was based on the White Bay power station near where I live in Rozelle. I love the variety of forms the building gives you, but the details of its history, from the broken windows to the decommissioned machinery, are all fascinating too. But I’m not the pioneer here, for example, Rohan Nicol—currently leading jewellery at ANU—made some wonderful pieces in 2004 based on the old Pyrmont incinerator designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Eric Nicholls. It is now sadly gone but it was a Sydney landmark for decades. I saw the pieces up close and personal when I went to the Powerhouse Museum recently. I was examining his work and their collection of mid-19th century goldfields jewellery. I was thrilled to be granted special access to see them. The very valuable gold pieces are wonderfully realistic images of gold mining, with mounds of tailings, men with hats and shovels, and surrounded by Australian flora and fauna – capturing a view of an industrial wasteland albeit artisanal and picturesque.

What I got from seeing Rohan Nicol’s work was this contemporary celebration of industrial architecture, of industrial history, done in an incredibly minimal way, where he had captured the essence of the relief sculptures that used to cover the Pyrmont incinerator. So I have tried to do something like that with the nearest and most important disused industrial building near my house, which was the White Bay power station. Google were about to refurbish it and make it their Australian head office but they have just backed out, so I have it all to myself!

Can you talk about some of the pieces in Thresholds in more detail?

Tanked is a necklace that plays with the verticality of the structure as well as its structural supports. It is this verticality that strikes visitors to the site and leaves them awestruck. However, it is also the surface and details that are so engaging. This piece is a necklace that bends at two points to adjust to the body. Its length is adjustable. I like its flexibility, subtle colour, layering and riveted construction, and, of course, its focus on detail.

The Mothvine brooches play with the aspect of this ‘edgeland’ where this vine and privet bush are vying to take over the site. These pieces capture the explosive aspects of the mothvine vine that doubly wraps around what it can find and tears itself apart to release thousands of seeds that lead to massive infestation. I found myself capturing the beauty in this scourge.

Pigeon Ground brooch. The infestations of mothvine are also accompanied by those of pigeons. The surface of the power station is punctuated by birds that make safe havens in the brickwork and the timber. I had taken a photo of a blacked-out window and in the corner sat a cooing pigeon. The building feels battened down – as indicated by the window, albeit this quest to block off nature fails. In this work I have exploited firescale to capture the engaging quality of that closed off surface. I was very happy with this piece because of its painterly quality in the silver but also in the variable patination.

Barrier brooch. This piece plays with the folded fabric that barricades dangerous surfaces in the edgeland around the site. The piece exploits the folded nature of the fabric and the posts that attempt but fail to keep it up. Shadows are an important element, revealed by the saw piercing at the back of the piece.

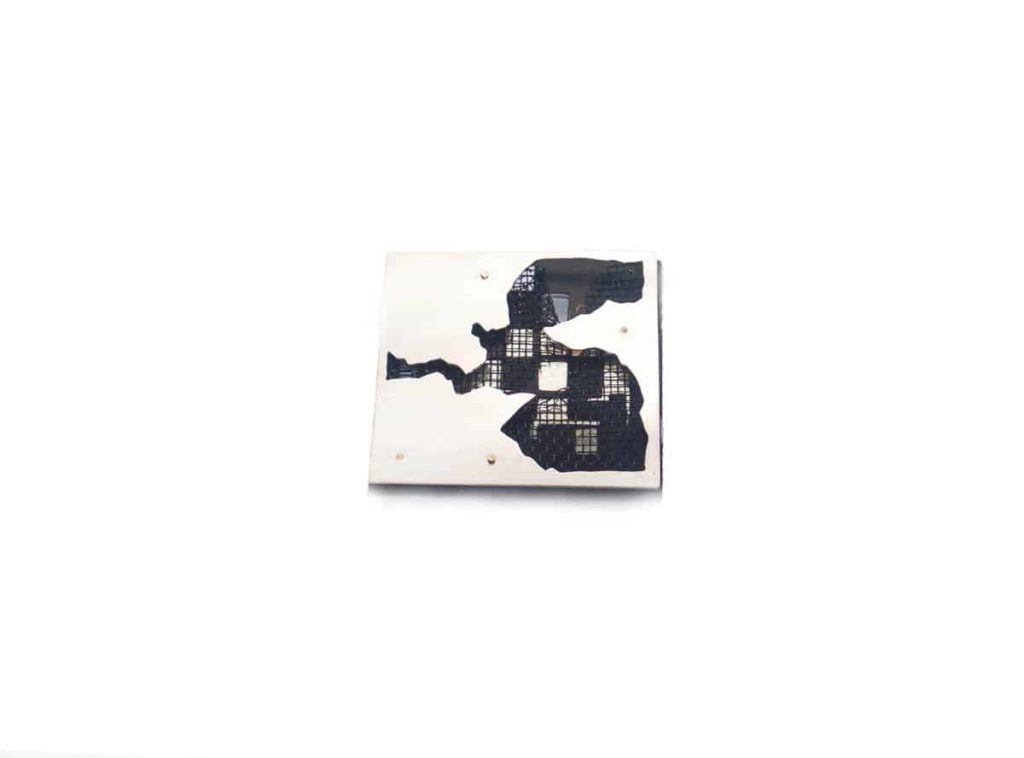

The Broken Window brooch plays with the layering that is the White Bay Power Station. The place is a huge rabbit warren where building has been added to building with scant regard for what is behind or next to any new construction. Consequently, life is revealed through layers; reflection stares back at you; screens suggest depth but obscure vision; glass is broken in strange and engaging ways. Surprisingly, the broken glass implies the Bays precinct itself – a site for major and contested development.

Rail brooch. Even the concrete ground has weathered into fascination. Cut across by rails it confounds someone trying to make sense of the place. I drew directly on brass with a lumicolour pen and etched with ferric chloride. I really like the direct action of making work in this way. The backplate is highly polished and reflects light through the punctuation of the brass surface.

What is coming next?

There is so much more in that site to explore and that is my immediate challenge. However, I am also keen to revisit the idea of a journey that takes me through an industrial landscape in transformation – rather like Iain Sinclair does in his literary works. Consequently, I am keen to go for a walk …

Author

Mark Stiles is currently a writer living in Sydney. Previously he had a short career in architecture and then a longer one in filmmaking, as a writer/director of documentaries. Recently he’s been teaching at various Sydney design schools. His interests lie in the history of Australian architecture and design. To this end he’s co-written a chapter in the anthology Sydney’s Martin Place (Allen & Unwin 2016) and is researching a proposed biography of the nineteenth century colonial architect James Barnet. He also curated several group shows, including: 2011 Meditation Suite (Gallery East, Clovelly), 2013 Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin Centenary Tribute (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2015 Japan : Australian Perspectives (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2016 An Unbounded World (Gallery East, Clovelly)

Mark Stiles is currently a writer living in Sydney. Previously he had a short career in architecture and then a longer one in filmmaking, as a writer/director of documentaries. Recently he’s been teaching at various Sydney design schools. His interests lie in the history of Australian architecture and design. To this end he’s co-written a chapter in the anthology Sydney’s Martin Place (Allen & Unwin 2016) and is researching a proposed biography of the nineteenth century colonial architect James Barnet. He also curated several group shows, including: 2011 Meditation Suite (Gallery East, Clovelly), 2013 Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin Centenary Tribute (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2015 Japan : Australian Perspectives (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2016 An Unbounded World (Gallery East, Clovelly)