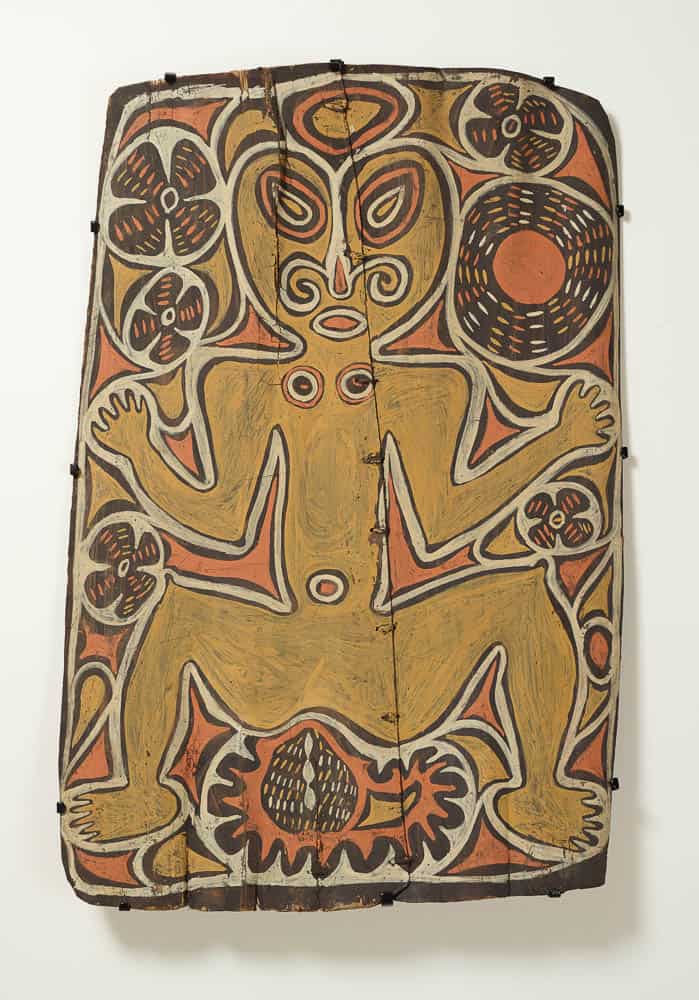

- Wiski Busengin Woknot (c1920–76) Ap Ma people, Kambot village Papua New Guinea Painting from ceremonial house (spirit figure with waterlillies and sun motif) mid-1900s, collected 1965 sago palm petioles, plant fibre, natural pigments 120.0 x 82.0 cm Art Gallery of New South Wales Purchased 1965 © Wiski Busengin Woknot Family

- Men’s ceremonial house (nbad ma) in Kambot village, 1950, photo: Fr. Petrus Beltjens SVD, Archive Societas Verbi Devini, Weltkulturan Museum, Frankfurt am Main

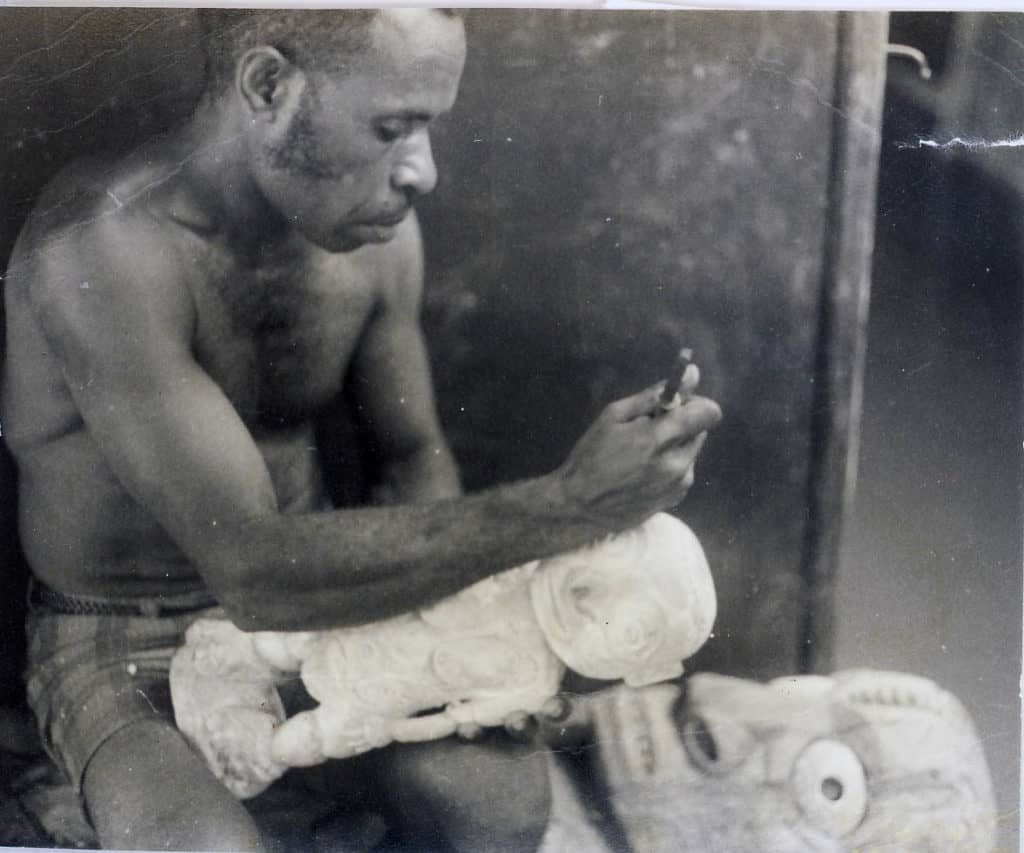

- Ignas Keram carving, Kambot 1973 Photo: Helen Dennett

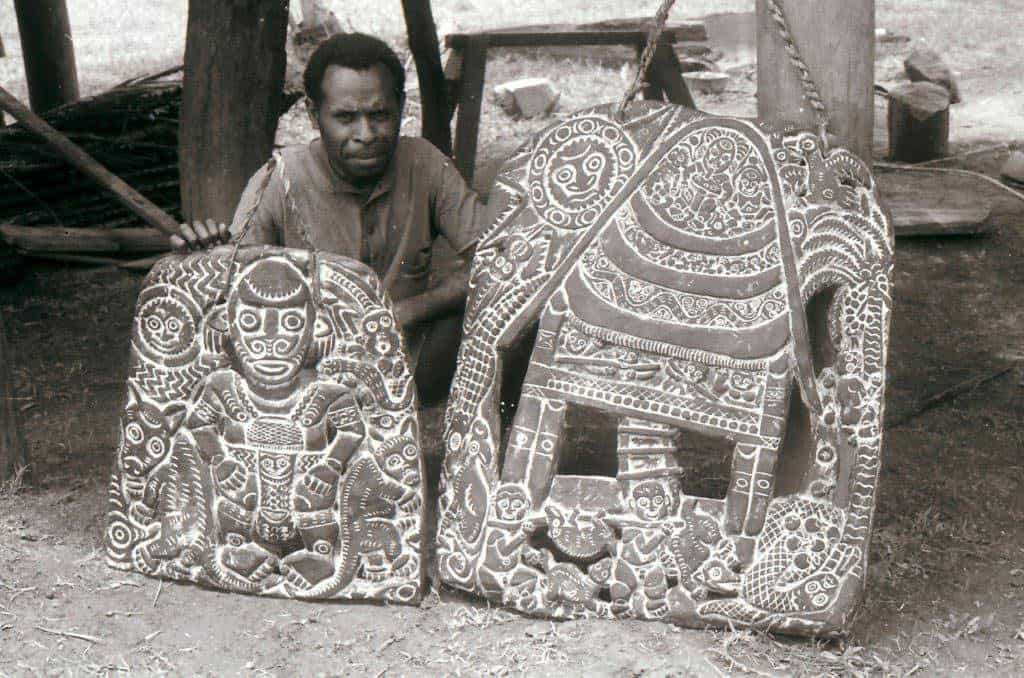

- Ignas Keram with two of his ‘storyboards’, Kambot 1974 Photo: Helen Dennett

- Wiski Busengin Woknot, Zacharias Waybenang and Kiri (l-r) with a ‘storyboard’, Angoram 1974 Photo: Helen Dennett

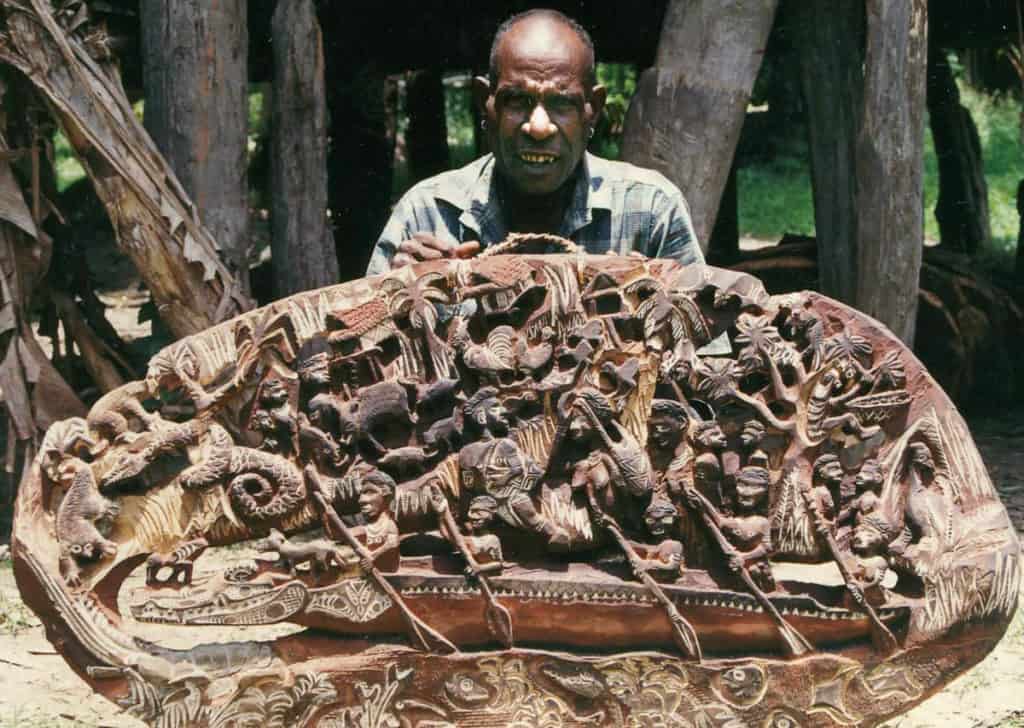

- Zacharias Waybenang with one of his ‘storyboards’, Kambot 1996 Photo: Helen Dennett

- Rudolph, Harry and Carl Waybenang with their ‘panggal’ paintings, August 2018, Kambot village, Photo: Helen Dennett

- Kambot dancers wearing sago-palm-frond skirts, August 2018, photo: Felicity Jenkins

- Sago-palm-frond skirts, Kambot village, August 2018, Photo: Helen Dennett

- Haus piksa, Kambot village, August 2018 Photo: Felicity Jenkins

- Natalie Wilson filming Harry and Rudolph Waybenang painting ‘panggal’ panels, Kambot village, August 2018, Photo: Felicity Jenkins

- Carl and Rudolph Waybenang preparing ‘panggal’ panels, Kambot village, August 2018 Photo: Felicity Jenkins

- The Waybenang family, including Zacharias (pale green shirt) and his brother Ignas Keram (black shirt) in front row, Kambot village, August 2018Photo: Felicity Jenkins

- Ignas Keram and Helen Dennett viewing image of ‘panggal’ panel by unnamed Kambot artist in AGNSW collection, Kambot village, August 2018 Photo: Felicity Jenkins

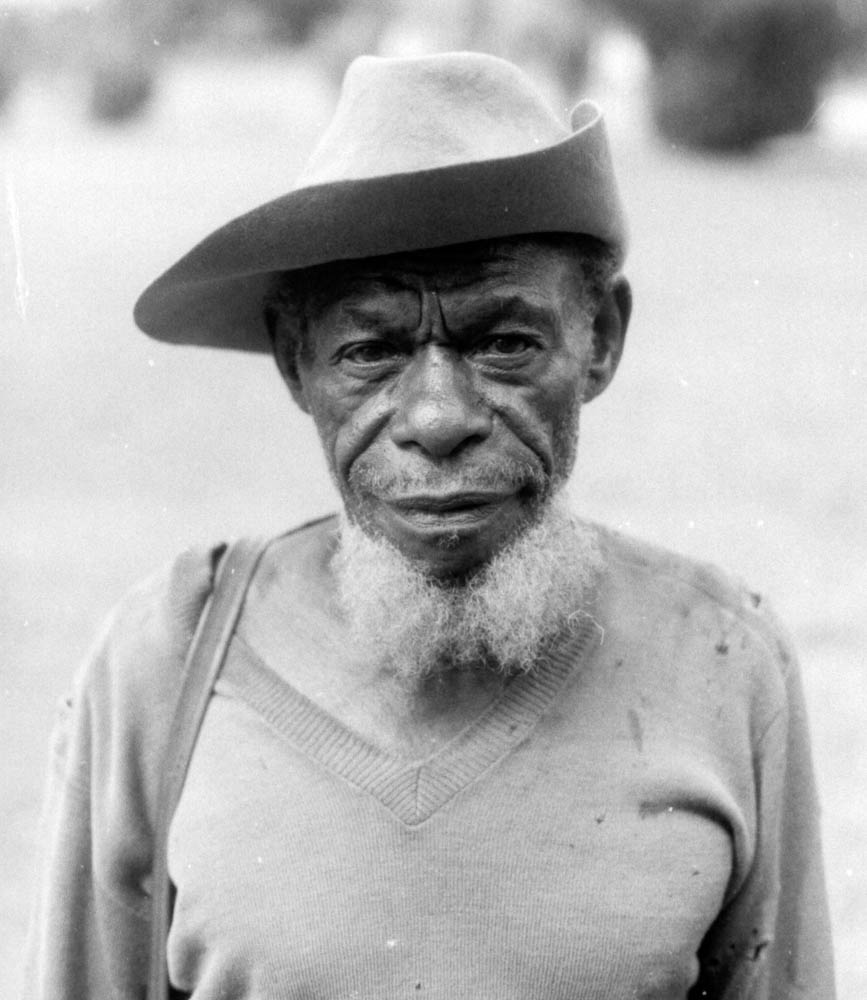

- Simon Nowep in Angoram, c1974, photo: Helen Dennett

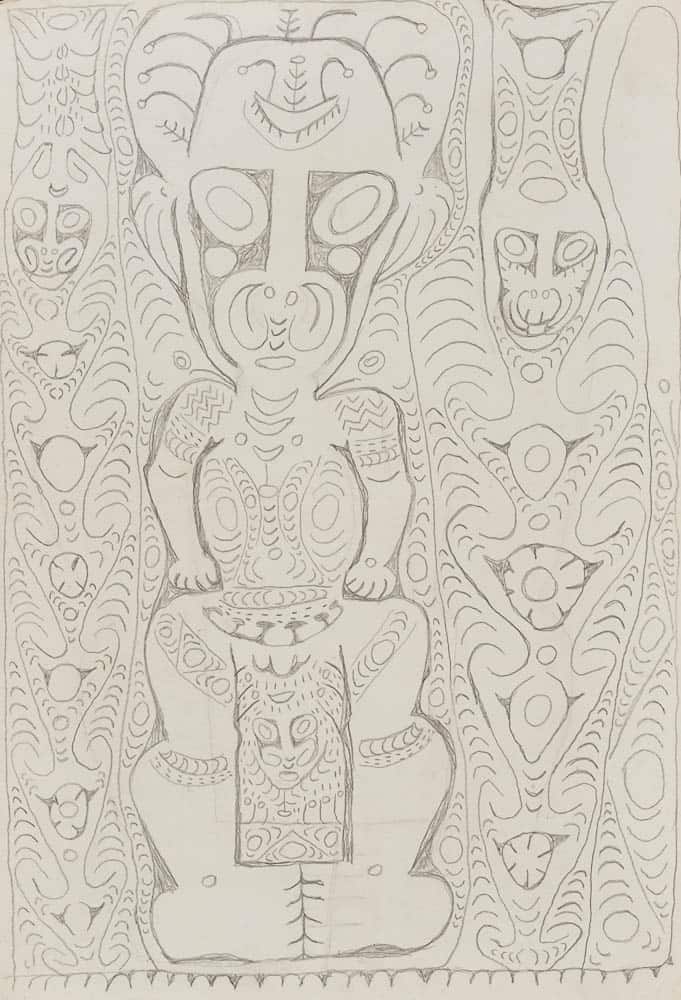

- Simon Nowep (c1902–84), Ap Ma people, Kambot village East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea Mopul 1973-73 pencil on buff wove paper 56 x 38 cm Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Mollie and Jim Gowing Bequest Fund 2017, © Simon Nowep Family

The last golden rays of sunlight sweep across the river. A canoe slowly glides downstream, smooth ripples fanning out in its wake, as the wooden paddle dips in and out of the water. Swollen grey clouds loom above the silhouetted forms of majestic garamut trees.

As I sit on the banks of the Keram River, a tributary of the great Sepik River of Papua New Guinea, the sounds of water lapping, crickets, chickens and the gentle laughter of small children playing, wash over me. Like most days on my trip, I feel the oppressive humidity pressing down on my skin, now glazed with a mingling of sunscreen, mosquito repellent and sweat. Travelling in the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea is not an easy undertaking, especially for someone who sits in a climate-controlled office in a major art museum every day. The experience of seeing this majestic country and meeting its people first hand, however, far outweighs any discomfort.

The people of Kambot village first saw westerners when members of the German-led 1912-13 Sepik River Expedition sailed up the Keram and marvelled at the enormous nbad ma 1.François Lupu, ‘Notes sur la circulation de trois objets dans la basse vallée du Sepik’, Journal de la Société des océanistes, n°40, tome 29, 1973, pp. 313-323. (haus tambaran in Tok Pisin; or men’s ceremonial houses) that lined the riverbanks. In May 1929, the Crane Pacific Expedition, financed by Chicago’s Field Museum, travelled to the Keram and photographed and filmed Kambot and the spectacular nbad ma. With their vast overhanging gables – said to resemble the open jaws of a crocodile – the nbad ma were adorned with paintings on sago petioles of spirits from the Kambot pantheon, including the paramount ancestor Mopul 2.Natalie Wilson, Melanesian art: Redux, Exhibition Guide, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2018, cat no 18.. By 1933, Father Ignaz Schwab of the Society of the Divine Word had established a mission there. World War II deeply affected the lives of those in Kambot, when the Japanese invasion of New Guinea brought destruction to the region. During the 1950s, Australian patrol officers occasionally visited the village, largely to offer War Damage Compensation to the Ap Ma people, whose villages were decimated during the war. Other missionaries came and went, followed in the 1960s and 70s by artefact dealers and anthropologists 3.Natalie Wilson, ‘Travelling north’, Look, Art Gallery Society of New South Wales, Sydney, Jan-Feb 2019, pp 24-25..

Today, few visitors to PNG travel to Kambot. When I arrived in August 2018, I was travelling with an Australian woman well-known to the people of Kambot. Helen Dennett had lived at the government station of Angoram from 1973 to 1975. Dennett encouraged artists, who would bring work to sell at the Angoram haus tambaran shop, to take pencils and paper back to their villages and to make drawings and recall important stories and legends. Two Kambot artists, Ignas Keram and Zacharias Waybenang, brought back drawings by another artist that impressed Dennett. She travelled to Kambot to meet the artist, Simon Nowep, who was then in his early 70s. A leading artist and a highly respected elder in his village, Nowep produced 90 drawings for Dennett between 1973 and 1975. Over four decades later, 75 of these drawings were acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, where I work as a curator of Australian and Pacific art.

I had wanted to return to the village with Helen Dennett, to meet some of the artists whom she had supported all those years ago, many now in their 80s. I also wanted to film some of the younger artists who are following in their footsteps, learning the traditional methods of painting Kambot’s ancestral mythological figures and ancestral spirits on sago petiole panels, known in Tok Pisin as panggal. Most importantly, I hoped to repatriate historical photographs of Kambot that had been taken over the past century, to give back to the villagers some of their history; not only images of the village itself, but as many pictures as I could find of objects now held in museums around the world, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

We were enthusiastically greeted by Zacharias Waybenang and his family, including three of his nine children, sons Harry, Carl and Rudolph. Zacharias has trained his sons in the Kambot tradition of painting on panggals and all are proficient in carving objects known as “storyboards”. Fashioned from the buttress root—or lenang—of the lendɘma tree 4.Roberta Colombo, Le storyboards di Kambot, PhD, University of Urbino, Italy, 1988-89, pp 45, 77-78., these “storyboards” are carved in openwork and semi-relief, and depict both mythological stories and scenes from everyday life. The people of Kambot welcomed us with singing and dancing, the women wearing their beautiful shredded-palm-frond skirts, rustling as they swayed.

Harry, Carl and Rudolph spent a day with me, demonstrating the steps required to complete a panggal. They prepared the dried and flattened sago petioles with an undercoat of black pigment, a mixture of charcoal and water. After the panels had dried, outlines of white clay were applied with brushes, delineating the figures and shapes across the surface, and drawn freehand with confidence and finesse. Finally, touches of orange ochre were added to some of the forms. The young men lamented the deterioration of the only nbad ma that remains in Kambot village, and the waning knowledge of most Kambot men in the skills of painting and carving.

Time spent with Zacharias, his brother Ignas Keram—a renowned carver—and village elders Gregory Wongio and Betika, together with many of the younger men of Kambot, gave us all an opportunity to discuss the images of works now found in museums around the world. It also underscored the need for researchers like myself to visit these communities now, before much of the knowledge held by these village elders is gone forever. I was delighted to discover that Gregory Wongio was, in fact, the son of the artist Wiski Busengin Woknot, who had lived and worked in nearby Wom village. Gregory was able to identify two works that had been collected in 1965 by the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ former deputy director Tony Tuckson, for the Gallery. Incredibly, they were by his father Wiski and now it is possible to give a name to this previously “unnamed artist” in the AGNSW collection. I was also able to meet one of Simon Nowep’s children, Simon Maru, and some of his grandchildren, to assure them that Nowep’s drawings were very much appreciated in their new home at the Gallery in Sydney.

On our final night in the village, we invited everyone from Kambot to the Waybenang haus win (communal “rest house”) to view historical photographs and films I had brought with me. As the sun set, the flickering glow of images thrown onto my strategically hung bedsheet from a battery-operated mini-projector, illuminated the faces of the men, women and children who had gathered to witness the haus piksa (cinema). Images of Kambot from the film Jungle islands, filmed by Sidney Schurcliff during the 1929 Crane Pacific Expedition, elicited much excitement but also sorrow, with many mourning the abandonment of so much of their traditional way of life over the past 90 years. However, bringing this important visual record of Kambot back to its people has afforded younger generations an opportunity to recall and reinvigorate the dynamic creative forces that have lain dormant for decades. It is my greatest wish that more Sepik communities might benefit from others undertaking similar journeys to my own, and that these historical visual records are reunited with the people to whom they belong.

Author

Natalie Wilson is Curator of Australian & Pacific art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, where she has worked since 1998. Natalie holds an MA (Art History & Theory) from the University of Sydney. Since 2006 she has curated many collection-based exhibitions at the AGNSW. She was awarded the 2011 Art Gallery Society of NSW Staff Development Scholarship to conduct research in PNG, where she travelled in the Highlands and along the Sepik River. Natalie was awarded the 2012 AGNSW Moya Dyring Studio Residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, where she developed the exhibition Plumes and pearlshells: art of the New Guinea highlands, held in 2014 at the AGNSW. In 2015, she organised the touring show Painter in Paradise: William Dobell in New Guinea, in collaboration with the SH Ervin Gallery. Following her Sepik journey in August 2018, Natalie curated Melanesian art: redux, held recently at the AGNSW.

Natalie Wilson is Curator of Australian & Pacific art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, where she has worked since 1998. Natalie holds an MA (Art History & Theory) from the University of Sydney. Since 2006 she has curated many collection-based exhibitions at the AGNSW. She was awarded the 2011 Art Gallery Society of NSW Staff Development Scholarship to conduct research in PNG, where she travelled in the Highlands and along the Sepik River. Natalie was awarded the 2012 AGNSW Moya Dyring Studio Residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, where she developed the exhibition Plumes and pearlshells: art of the New Guinea highlands, held in 2014 at the AGNSW. In 2015, she organised the touring show Painter in Paradise: William Dobell in New Guinea, in collaboration with the SH Ervin Gallery. Following her Sepik journey in August 2018, Natalie curated Melanesian art: redux, held recently at the AGNSW.

References

| ↑1 | François Lupu, ‘Notes sur la circulation de trois objets dans la basse vallée du Sepik’, Journal de la Société des océanistes, n°40, tome 29, 1973, pp. 313-323. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Natalie Wilson, Melanesian art: Redux, Exhibition Guide, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2018, cat no 18. |

| ↑3 | Natalie Wilson, ‘Travelling north’, Look, Art Gallery Society of New South Wales, Sydney, Jan-Feb 2019, pp 24-25. |

| ↑4 | Roberta Colombo, Le storyboards di Kambot, PhD, University of Urbino, Italy, 1988-89, pp 45, 77-78. |

Comments

Dear Natalie,

I am very happy to read this article about your time in Kambot! I was there a couple times in 2014! I traveled with Elizabeth Cox and I also met Helen Dennette. We should exchange experiences! I was there as a documentarist working together also with the Museum of Culture in Basel, Switzerland and I did there the documentary Kanu belong Kram: https://vimeo.com/172908511

Lets see when we can go back to Kambot!

best regards – Daniel

Thank you so much Natalie for putting together what I just read. I’m from Kambot and have been away from my people since 1994 after completing high school.

I did my primary school grade 6 at Kambot and all the names you collected with the story are clear. These are my uncles and by now have passed on.

No words can express how thankful I am to access and read what you have documented for Kambot.

Thank you Natalie for a well documented piece of history for my village; Kambot. You came from a far away land to visit my village and to remind us of our rich unique art culture and we are very grateful. Apart from the ‘haus tambarans’ and the arts, Kambot also has a unique chief village system. The chiefs are by birth rights. My father’s uncle from his mothers side was of the last village chief-line. His name is Dambun. Ingas Keram and his brothers are my father’s cousins and they also have certain rights to the village arts. Simon Nowep is a village elder and also an artist by village rights.

Thank you.