Photo by Cassandra Lehman

Cassandra Lehman reflects on her magical journey through Indonesia, where art extends far beyond the museum.

Indonesia has a population of over 250 million people and is the most populous Islamic democracy on earth. Australia has much to gain in maintaining an ongoing understanding and respectful appreciation for Indonesia and its arts and culture. Since undertaking a residency in Jogjakarta, I have committed my efforts to building a bridge between the two countries and slowly gained recognition as an influential and knowledgeable champion of Indonesian contemporary art. I am dedicated to expanding this conversation and continue to foster the exchange and dialogue between the two countries, through the arts.

Stepping onto the tarmac of Adisutjipto Airport for the first time in 2009, I was blanketed by sticky heat with a whiff of benzene. The atmosphere, filled with animated chatter and scooter engines, instantly transported me back to childhood memories of kampongs and skinny dogs, orchids and prayer calls. As an Australian army brat, growing up in the 70s in Singapore left me with a sense of longing and nostalgia for a home to which I could never return. Thanks to a grant from Asialink, and an artist’s residency in Jogjakarta, I finally found the place to fill that void.

My hosts, the founders of Cemeti Arthouse, Mella Jarsma and Nindityo Adipurnomo, arranged a little kampong house for me close to their own and in walking distance to the gallery. They introduced me around and asked me what sort of assistant I’d like. I requested someone brave, preferably a woman. They excelled in selecting Ina. Nicknamed the Queen of Doctrine and resplendent with animal-rights tattoos, Ina knew everyone and everyone knew Ina. On the back of her motorbike, I began my residency by visiting studios and galleries during the day and attending openings and performances every single night.

In the midst of a mostly commercially driven arts scene, Cemeti, established in 1988, maintained a focus on the avant-garde and launched a number of significant Indonesian contemporary art careers. Landing Soon, their long-established residency program brought Dutch artists together with emerging and established local artists. I found inspiration in the outcomes of these exchanges, the ongoing exhibitions, research, publications and collaborations.

Learning through immersion, I strove to understand the visual language and recognise the cultural signifiers in the profuse artwork. I also became fascinated by the differences between the support mechanisms and driving forces behind Indonesian Contemporary Art and elsewhere.

The Special Region of Jogjakarta, on the island of Java, is a Sultanate. As a university town, the highly transitory population of approximately 3.8 million come from all over the more than 13,000 islands and regions of greater Indonesia. Each region has a unique set of traditional cultural and craft practices, including elements of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and animism.

ISI (Institute Seni Indonesia – Indonesia Institute of The Arts) is arguably the most famous and reputable art college in Jogjakarta and the visual and performing arts, crafts and design scene of Indonesia. ISI was established in 1984, as an amalgamation of visual arts, dance and music schools, dating back to the early 1950s. Making it to ISI is a huge accomplishment in itself, as statistically, there are very few places for the full-time study of art in the country at all, compared, for example, to Australia. In 2009, it was not uncommon for young student artists to already have a following and a collector base before commencing their formal studies.

To become a seniman, or an artist, was generally seen as a viable and worthy career, with potential for great success. Divisions of class and culture didn’t seem to be relevant and I quickly found myself enjoying the inclusivity, mingling with established artists and young students alike, from all over the country. I learned that it’s quite acceptable for young artists to knock on the door of an established studio, to ask for guidance and feedback from “the master” who willingly gave them time.

I was awarded my residency in order to create a project entitled The Museum of the Unworthy. To make a long story short, this involved a creative engagement with the local landfill site, to consider the role of the artist in creating desire, consumption, excess and ultimately, waste. This became a collaborative project with a number of local artists.

The notion of museum is perhaps a somewhat cultural imposition, brought to Indonesia by Dutch colonists. I found this as central in coming to understand the position and framework for this vibrant arts scene. Even before I started, I began to understand how Eurocentric my own education and approach actually was. I had copied Van Gogh’s sunflowers in crayon at the age of 5, after seeing the original in a museum. By contrast, emerging artist Lugas Syllabus, who grew up in a small village, had never seen an exhibition nor had the opportunity to visit a museum until coming to study at ISI.

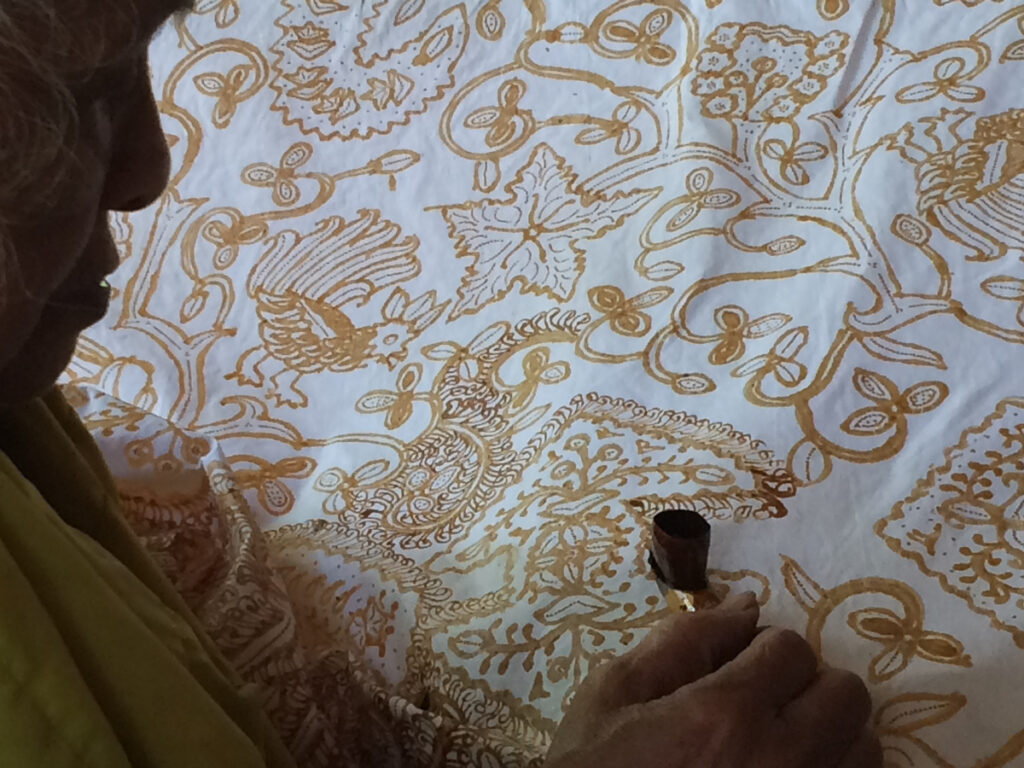

Batik artisan, Mbah Bar (Bariah) Imogiri Village, photo by Cassandra Lehman

I visited several museums in Jogjakarta during that first trip. My favourite was the Museum Biologi Universitas Gadjah Mada. I was utterly fascinated by the dank and outdated displays and stained cardboard labels. Taxidermy specimens stood in vitrines surrounded by little piles of their own shed fur. Specimen jars contained unrecognisable biological matter, half-submerged in brown liquid. Elsewhere, I distinctly remember a display case containing a set of stained oven mitts.

This neglect was in stark contrast to the glamourous, atmosphere controlled shopping malls and soon to follow, the architecturally designed commercial art galleries and hotels springing up around the city.

Indonesian government places a high value in preserving traditional culture. Batik patterns are worn with pride, different shapes and colours signify different regions, some patterns are reserved for royalty or high officials or for ritual purposes. Contemporary art is not seen in the same light, however, and perhaps this is reflected in the fact that although there is a batik museum, there are no government-funded museums for the contemporary arts.

Italian art conservator Michaela Anselmini was appointed as the first official conservator to the Sultan, at the Kraton (palace) of Jogjakarta. She has been championing art restoration and preservation, teaching and working in Indonesia for a number of years. In 2019 I accompanied a group of international museum benefactors on a tour of Indonesia, as an expert curator. We were privileged to witness Micheala and her team working at the Kraton on the restoration of three major portraits from the 1800s. The master painter, Raden Saleh is considered the first great Western-trained Indonesian artist. As the subjects of the Raden Saleh portraits were the Sultan and his wives, the paintings are therefore considered sacred objects and treated with the utmost respect and reverence. Rituals had to be performed before the conservation could begin, and before touching them, staff must bow to the paintings. The portraits had suffered damage from the humidity and until an air-conditioned and atmosphere controlled space could be provided, the conservations studio, initially, was in an open-air pavilion.

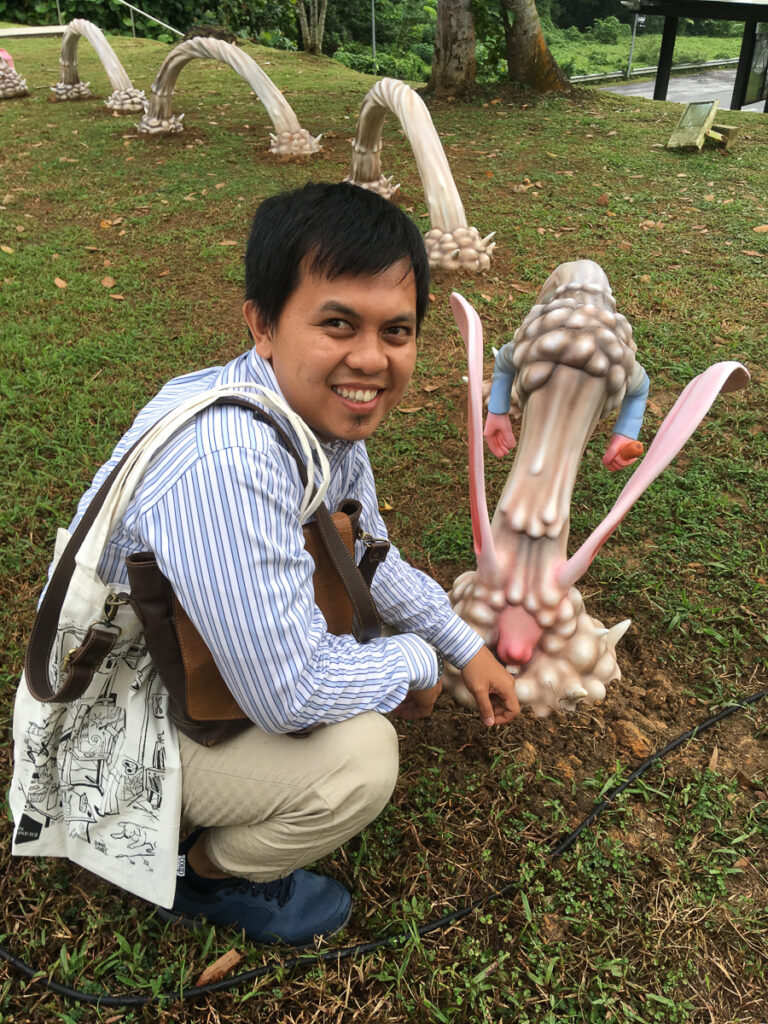

Lugas Syllabus with his work Catch Yourself If You Can. Disini Festival , Gilman Barrack . Singapore 2018. Photo by Cassandra Lehman

Jakarta’s recently opened state of the art, architecturally designed museum, Macan, focuses on modern and contemporary art from Indonesia and around the world. It appears outwardly to be a state-run institution but was actually built to house a private collection. Over the past decade, I have visited a number of private homes and museums, some with outstanding art collections. I wondered about the consistency or lack of collection policies, record keeping and management for these collections. ISI, for example, has for decades been collecting one work from each graduating student. I learned this on a tour of the faculty when I asked about the large pile of dishevelled paintings, randomly stacked in a busy corridor.

Privately owned museums are subject to the personal tastes, preferences and interests of their owners. To my mind, capital and the market rather than the sanction of museums has seemingly validated the Indonesian arts scene. For better or worse, as a result, contemporary art in Jogjakarta has become a “rock star”.

Artjog is a unique, annual art fair modelled similarly to an art biennale, curated and run locally as a commercial venture. For the opening of Artjog 13, in 2013, as the guest of one of the featured artists, I found myself swallowed up in a crowd of at least 1000 mostly young people, all trying to pay the hefty entry fee and get in the door. The level of excitement was unlike anything I’d ever witnessed at a gallery, museum or art fair in Australia or elsewhere. Filtered through 250 million people, the artwork that permeates to the surface in events such as this is preferred by not just the local community and collectors but increasingly, by the global art market.

The themes that run through the works are rich and ripe for researching. In the past decade, I have often been asked to write, curate, speak and assist with the English translations for catalogues, artist’s statements, essays, didactics and articles. Much of what I have learned about Indonesian traditional crafts and cultures has been through these interactions.

- Jumaadi, Cassandra and Fauzia Harumi at the opening of Jumaadi – House of Shadow at artisan, 2019, Photo by Mick Richards

Writing for Lugas Syllabus about his imagery, drawn from the stories told to him by his grandfather, led me to the myths and legends of the Gumay people of Sumatra and the unknown origins of the Monoliths of the Pagar Alam region. Writing for Jumaadi brought me to an appreciation of the rice primed temple paintings in the Kamasan region of Bali. Jumaadi’s use of intricately cut buffalo hide led me to research the history of wayang and to recognise the motifs in the work of others such as Entang Wiharso. Heri Dono’s work taught me about more recent histories and colloquialisms.

Over the past decade, I have slowly shifted my life’s focus to building a bridge between the two countries. I have conducted a number of tours and visits for students, academics, collectors, artists and benefactors, introducing them to the fabulous and fascinating world of art from Jogjakarta and Indonesia. I have eaten humble meals in villages and dined with billionaires. I have learned that there is much still to learn. This work has taken me down an unexpected path, although I am no longer a practising artist, my life is full and I could not be happier. I am only slightly embarrassed to admit that, although I have never really learned how to speak the language, I manage to get by with what I call “one-word bahasa”. I always look forward to stepping onto the tarmac again, to be blanketed with the warmth and humour of my second home.

Author

With over two decades of industry experience, Cassandra Lehman has worked as a curator, gallery director, arts policy writer, and theatre production manager. She has travelled extensively, gaining a wealth of knowledge and experience in working with Australian, Torres Strait Island and Aboriginal artists, and South-East Asian arts communities. Cassandra graduated with a Master of Visual Arts from Queensland College of Art, Griffith University in 2002 and currently lives in Brisbane, where she is co-curator at Artisan. Passionately committed to broadening audiences for the contemporary arts, Cassandra’s primary focus continues to be challenging audience perceptions and extending intercultural understanding through the arts.

With over two decades of industry experience, Cassandra Lehman has worked as a curator, gallery director, arts policy writer, and theatre production manager. She has travelled extensively, gaining a wealth of knowledge and experience in working with Australian, Torres Strait Island and Aboriginal artists, and South-East Asian arts communities. Cassandra graduated with a Master of Visual Arts from Queensland College of Art, Griffith University in 2002 and currently lives in Brisbane, where she is co-curator at Artisan. Passionately committed to broadening audiences for the contemporary arts, Cassandra’s primary focus continues to be challenging audience perceptions and extending intercultural understanding through the arts.