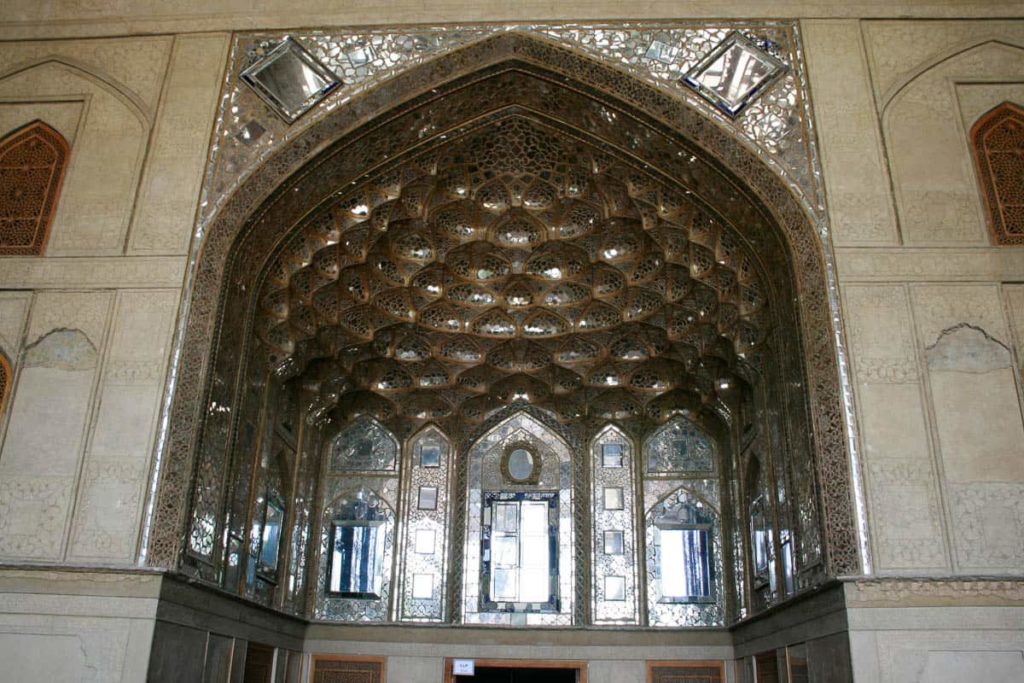

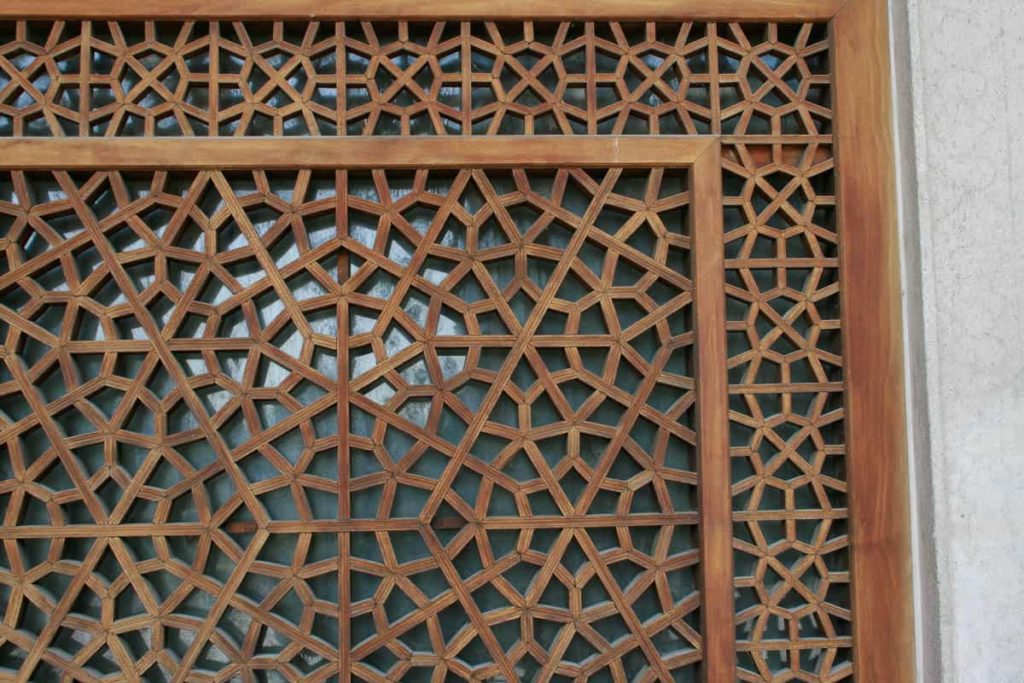

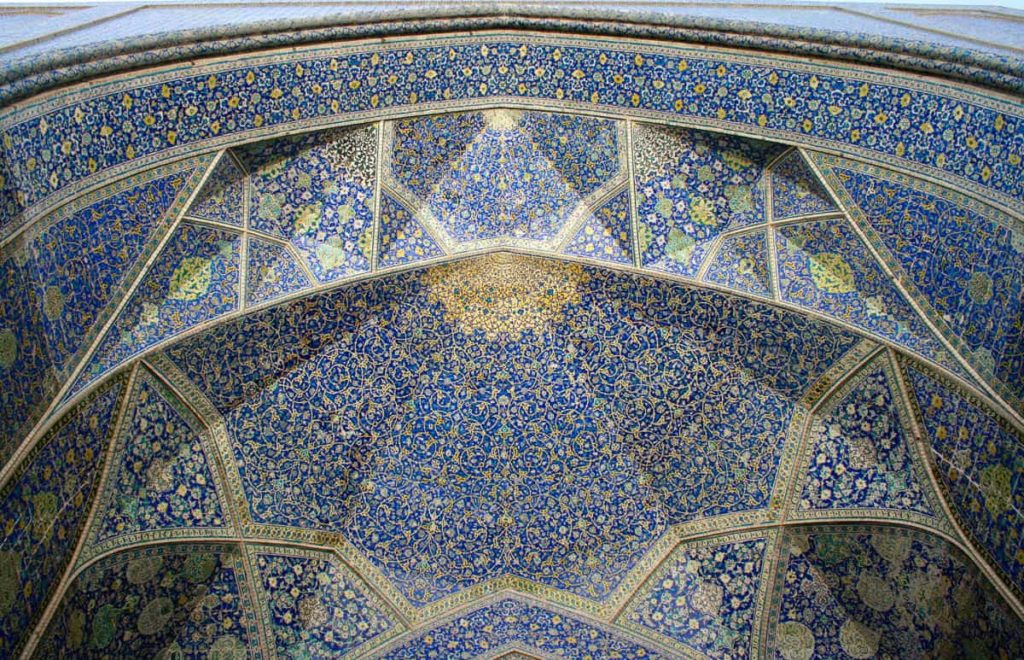

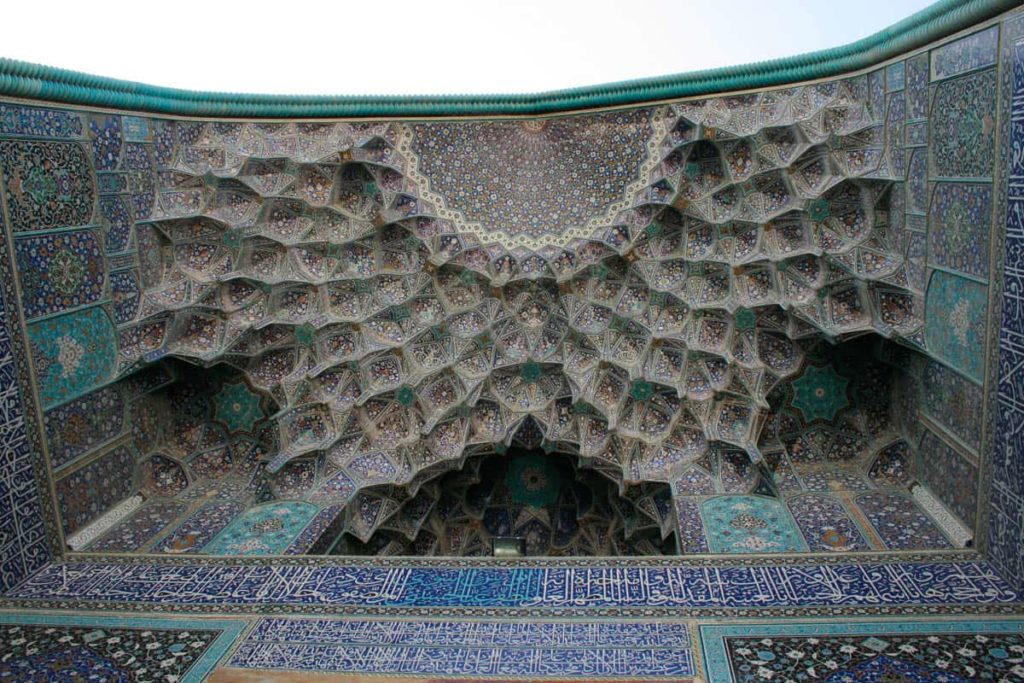

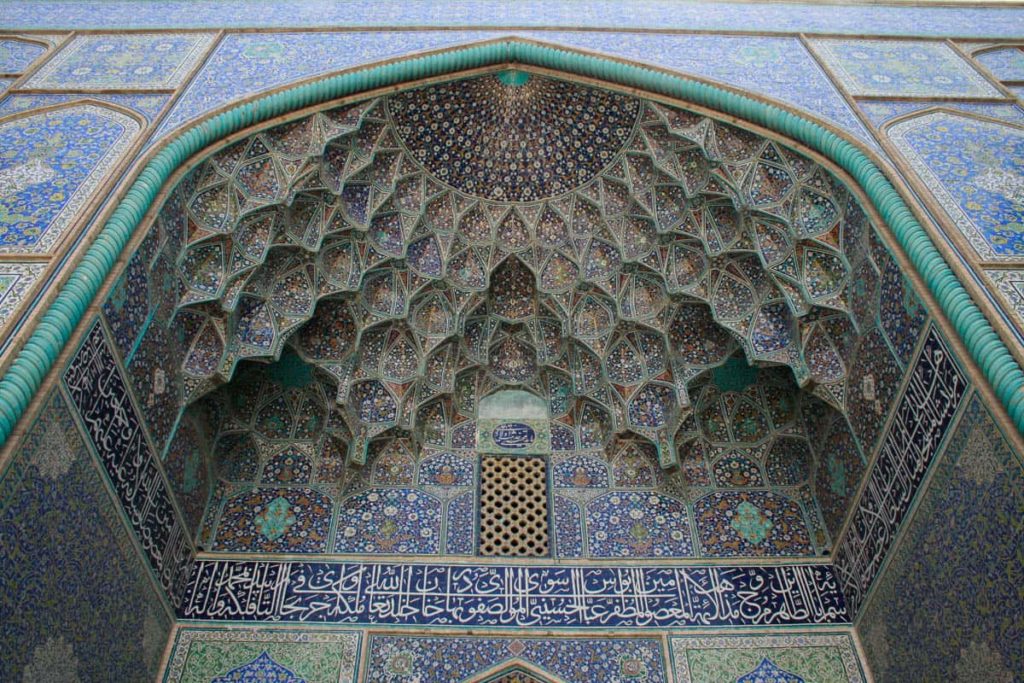

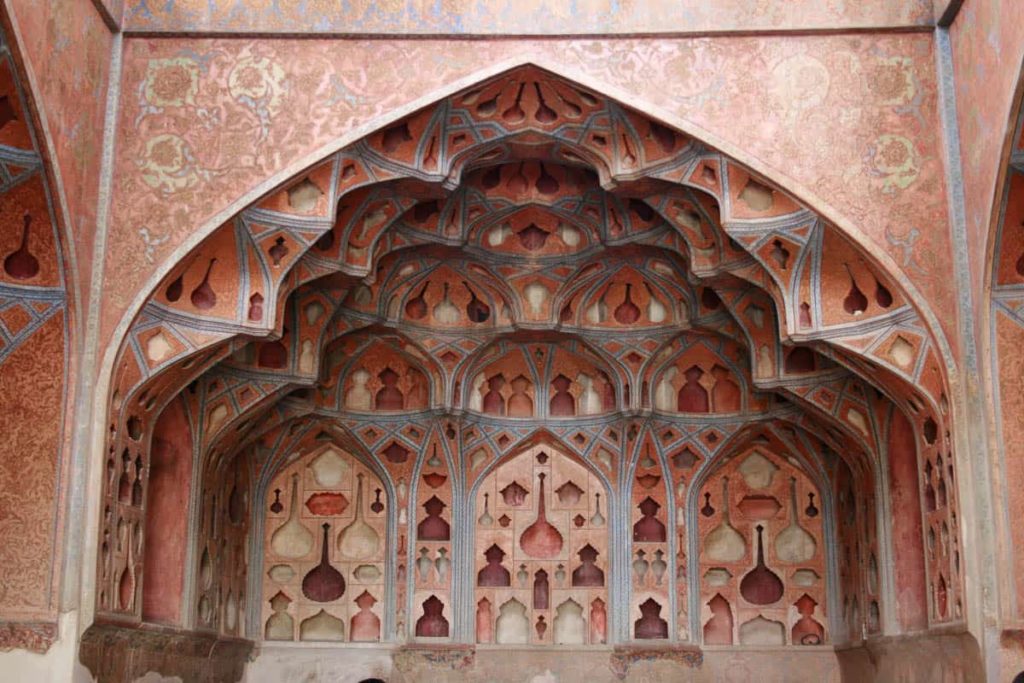

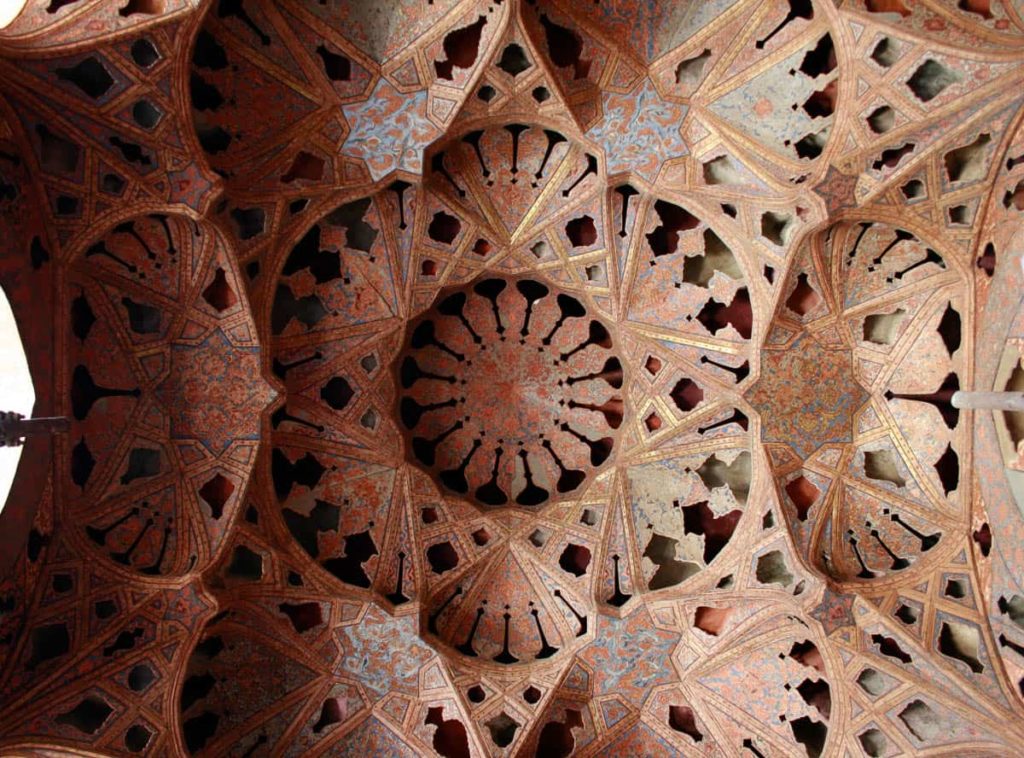

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

- Scene from Isfahan, photo: Merhnoosh Ganji

I had read about Mehrnoosh Ganji. She was a young talented young Iranian woman who had migrated to Australia in 2012 and had continued her passion of becoming a jewellery designer. I had seen her work in pictures, and was looking forward to seeing her and the pieces physically to try and understand more.

You can also download this essay to print yourself as a PDF here.

I met Mehrnoosh in a coffee shop in Melbourne’s Elwood, the day after the controversial debate between Iranian Sydney Senator Sam Dastyari and the One Nation Party Leader Pauline Hanson, where she seemed outrageously surprised to find out he identified himself as Muslim. As someone in a similar situation as Dastyari, born Iranian Muslim but not actively practising, the debate had again stirred up questions about my own multiplicities of identities. How did someone like myself, and may be Mehrnoosh, define ourselves in Australia? It was with this in the back of my mind that I met Mehrnoosh for the first time.

Mehrnoosh was a beautiful and petite young woman with silky dark hair. When we met, she was wearing her signature design The Lotus Transporter, as a pendant. The Lotus Transporter is a 15-sided decorative object that resembles a very modern interpretation of the pomegranate that opens up to the shape of an eye revealing a hidden tiny secret box. Crafted into its sides are delicate red flower petals, and when it closes there are four ruby red garnet gemstones that sit at the top.

As we sat down, and after some short introductions about each other, I was about to take hold of and open up the Lotus Transporter, when a young attractive Anglo waiter came up to take our order, looked at me and at Mehrnoosh, and smiled. “That is a beautiful necklace,” he said. “Where are guys you from?”

This is a seemingly simple question, usually with a straightforward answer. The answer usually gives a sense of belonging and allegiance to a city or a country. But at that moment, in my frame of mind, the question took me by surprise. I looked at Mehrnoosh and smiled.

What was I to say to him? His question had tapped into the very whirlpool of ideas that had preoccupied me.

For Mehrnoosh, and myself, and the likes of us, the answer is not so simple. It opens up questions that transcend belonging to a physical space and instead, it becomes a debate of cultural, historical, social and even political identity.

As I continued to ponder over the Lotus Transporter, I told him, “Where do you think?”

“I’ll think about it,” he said as he walked away taking our orders.

This had not been an uncommon question. But the answer, no matter what I had said, would have opened up a series of expected responses along the same lines.

If I had said, “Persian,’”it would have attracted a predictable response, such as, “Oh, where is that?” Or, “That’s not a country anymore, is it?” Had he been older and more romantic, he might have started to comment on Persian sophistication, culture, poetry, and its contributions to the world. If not, the conversation might have led to carpets, and cats, and perhaps ended with, “Why not Iranian?”

If I had said, “Iranian,” the reaction might have varied, as it usually is. It might have been, “Oh, that’s interesting,” and would have led to questions of more contemporary topics of politics, Islam, and migration. At some point, if he was trying to figure us out, he might have said, “I have a friend who called herself Persian, why is that?”

And the cycle of explanations would have continued.

I am sure that all Iranians who live overseas have, at some point or another, faced this type of encounter, just like Mehrnoosh and I had then. And all have tried to understand this situation as much as explain it. In this process, I am sure none of us have come to an absolute conclusion to identify ourselves as either Persian or Iranian.

As a researcher, I have always been interested in examining how Iranians abroad attempt to straddle and reflect their identity issues, like the one we had just encountered. I have noticed that it forms a strong running theme in their various artistic practices. My meeting with Mehrnoosh was precisely to see how her pieces explore this concept.

To be encountered with the young man’s question in the cafe had set the tone of our meeting, because it highlighted the fact that understanding and explaining one’s Iranian identity abroad has more complicated elements and nuances than a deep personal contemplation of individual perceptions. This identity—how we see ourselves and how others see us—is usually formed in reflection of and negotiation with the way Iran is perceived beyond its borders, by ordinary people like the young waiter. And that divide between Persia/Iran in the Western mind plays a significant part in this conversation.

Usually, for the non-Iranian mind, the term Persia encapsulates the mysterious East. It brings forth all sorts of exotic sensations and a mystic allure, interrupted by the 1979 revolution. The sudden exposure of Iran on the world stage after the hostage crisis, when the modern Iranian nation state, its people and leadership became synonymous with Islamic extremism, totalitarianism, and human rights issues, challenged and shattered the relatively positive image the country previously had. For those who migrated out of Iran, specially soon after the Islamic revolution, the image of the modern nation of Islamic Republic of Iran, brought negative associations, even leading to discrimination.

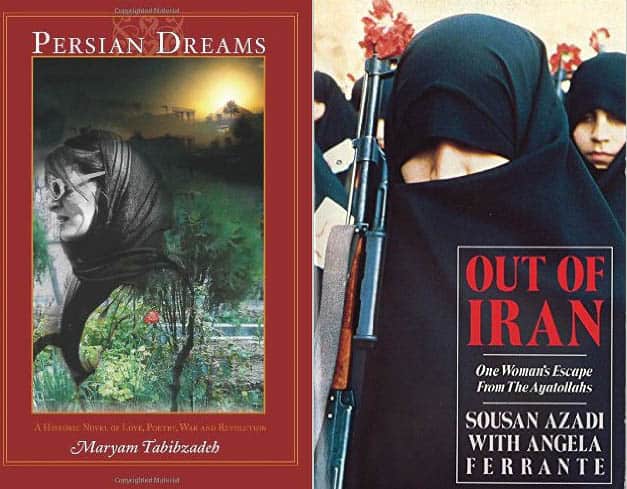

Iranian cultural producers abroad have often used this Western associated division to reflect the kind of message they want to portray. Looking at some of the titles in the body of Iranian writing in English over the last three and half decades makes this clear. Titles such as Sattareh Farman-Farmanian’s Daughter of Persia, Afshin Molavi’s Persian Pilgrimages: Journeys Across Iran, Maryam Tabibzadeh’s Persian Dreams, Dalia Sofer’s Septembers of Shiraz, automatically attract the readers to a sense of allure, a journey inwards into the exotic.

On the other hand, titles that use the word Iran in many cases are often immediately linked with a negative association to the nation state of Iran. For example, the titles in the works of Sousan Azadi’s Out of Iran: One Woman’s Escape from the Ayatollahs, Banafshe Serov’s Under a Starless Sky: A Family’s Escape from Iran, and Iran Awaken: One Woman’s Journey to Reclaim her Life and Country, immediately conjure up images not as positive, drawing less on the allure of Persia, but highlighting issues of the modern Iranian nation state.

Despite this, while we Iranians often play between how we want to be projected in a particular situation beyond the borders of Iran, the fact of the matter is that the seeming duality of identity is not new for the Iranian soul. Inside Iran, there is often no need for its explanation. Distance, and an outsider’s perspective, only brings it to our attention.

From my viewpoint, and I would assume for most of my countrymen, to be identified as Persian or Iranian is not a matter of difference or duality to be broken down as such—unless of course for some ethnic groups who are fighting for their rights for independence to separate themselves from the modern Iranian nation state. To me, this is instead a reflection of the existence of the ongoing straddling of tradition and modernity that has forged the modern Iranian identity inside Iran over centuries, the epitome of which was highlighted rather recently, in 1935, when the Shah changed the name of the country to its modern counterpart of Iran.

People like Mehrnoosh and I, who were now sitting across each other in a cafe in Melbourne, bonding over her creations, we are people whose sense of identity has been constructed under the push and pull of expanding empires, Islamic invasions, and modern influences. Our grandmothers were the ones unveiled under the guise of modernity only to be veiled again by Islamic traditions. We live by three different calendars every day, celebrate the Zoroastrian New Year Nou Rouz, and throw religious ceremonies in honour of various saints turning up in branded American and European clothing and miniskirts. We are the ones who will equally enjoy a traditional Persian poem sung by classic Iranian singer Shajarian as much as one followed immediately by Madonna. In all this, we are equally Persian, carrying with us the deep traditions handed down to us, as we much as we are Iranians, living in the modern Iranian Islamic nation state.

Yet, this is not an easy condition to be in. We both knew this, I thought, as I watched Mehrnoosh lay out the other pieces of her work on the table. It is one that continuously calls for negotiations and reconsiderations of values and belief systems. In this shifting world, there is always the question of what are the traditions worth hanging onto, and what are the ones we must let go in order to be modern citizens? More importantly, what are the values, ideas, and shapes that define us as individuals with an identifiable thread to a specific culture and tradition?

And I could see this theme of negotiating the traditional and the modern reflected in Mehrnoosh’s jewelry pieces.

But this is not a new concern. Throughout recent Iranian history, particularly since Iran’s encounter with modernity as early as the late 1800s, Iranian artists in various fields have tried to grapple with, draw upon, and represent the meeting point of tradition and modernity to express themselves and their situation.

This can be traced back to as early as the Qajar Shahs’ burgeoning encounter with Europe in the nineteenth century, to their import of Western art forms and mediums into their courts, and through their encouragement of this exchange by sending Iranian students to study overseas on scholarships. When they came back, the students brought with them Western influences, in all areas of life, previously not seen in Iran. This was something that reverberated through the entire country, with ongoing reflections in cultural and artistic practices. With the advent of technology, and the accessibility of these new mediums to the masses, and the introduction of Western influences on everyday Iranian life, artists thus began to employ these new imported forms and blended them with their own Iranian tradition to express a new content that reflected their current situation.

This was something that could be seen throughout the arts. In literature, for example, we can see how Western and modern influences have affected the Iranian story telling form. For instance, the novel as a form of literary expression in Iranian literature only became popular with the Iranian writers’ encounter of it in earnest only in the early 1900s. People like Mohammad Ali Jamalzadeh and Sadegh Hedayat, who were heavily influenced by Western literature, could be considered some of the pioneers of exploring the overlapping of Persian language with modern Western forms leading to the exploration of some amazing and unique narrative voices to emerge from Iran. Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl, a Kafkaesque novella, can be named as one of the forerunners of this tradition.

We see this in in film production, too (a Western construct imported into Iran by the Qajar Shahs in the early 1900s), which has consequently led to the modern form being used to visually express some of the most spellbinding narratives, drawn from traditional Persian literature. The master of this combination, no doubt, could be named as the late director extraordinaire, Abbas Kiarostami, whose films like Where is the Friend’s Home?, among others, visualizes certain poetic resonances in Persian literary tradition.

In short, it can be said that Iranian artists have continuously grappled and drawn inspiration from the congruence of their traditional sensibilities and modern influences—the very landscape that forms their everyday life in Iran.

I was thinking about these things, and how we would even begin to convey and demonstrate this complexity to someone like the young waiter, as I chatted with Mehrnoosh and looked over the Lotus Transporter carefully.

- Mehrnoosh Ganji, Lotus Transporter, 2014, Sterling silver, fine silver, enamel, garnet, blue topaz, citrine, dimensions (6 x 3 x 4cm)

- Mehrnoosh Ganji, Lotus Transporter, 2014, Sterling silver, fine silver, enamel, garnet, blue topaz, citrine, dimensions (6 x 3 x 4cm)

It was obvious that the piece that I was holding was a tangible reflection of our collective experiences, the very idea I had been thinking about. Elegantly designed, meticulously handcrafted (not only the Lotus Transporter, but also the other objects that were displayed on the table) encapsulate and recount the harmonious tensions, reflecting the visceral force that have formed the Iranian sense of identity over the years. As wearable, elegant masterpieces Mehrnoosh’s work demonstrates to me the complexities of modern Iranian experiences.

I emphasize that the piece, like the Lotus Transporter, encapsulates the complexities of modern Iranian experiences because, although it carries with it very subtly elements of a Persian symbol, the pomegranate, there is nothing traditional about it. In fact, the object itself as a whole is extremely modern. There are right angles, straight lines, and sharp edges, all of which are telling of a modern piece of jewellery or architecture.

Yet, the red ruby gems, the soft petals crafted on the sides, and the fact that when it is closed it resembles a modern interpretation of the pomegranate, bring in elements that speak of a tradition deeply embedded.

It is through the juxtaposition of the sharpness of the edges, something very modern, mixed with the softness of the petals, curves that represent tradition, that Mehrnoosh has captured the complexities of contemporary Iranian experience. Her work is the essence of how we would define ourselves. Like us, it is not completely modern, not completely traditional. It is a well-balanced harmonious blending of the two, leading to a unique form resting in between the two realms.

When I held the piece, and opened it up, I understood why she has called it the Lotus Transporter. In different cultures, the symbol of the lotus is one of rebirth, purity, and transcending into other realms of existence. And the Lotus Transporter in its shape and the ruby gems, reminded me of a red juicy pomegranate, and transported me back to memories of my childhood in Iran.

Growing up as a child in Tehran, during the Iran-Iraq war, on cold winter nights, when the electricity would be cut off without warning, my family would sometimes cuddle together under a korsi my grandmother had set up and we would eat pomegranates under the light of small oil lamps or candles.

“Anaar is a fruit from heaven, each seed containing the universe within it” my grandmother used to say as she would crack open the rough exterior of a pomegranate just enough for us to see the glistening juicy sweet and sour pearls that hid inside, anticipating their texture and taste under our tongue. “So you must respect and savour every seed and hold it dear,” she would say as she would hand out the cut fruit, as we carefully, but with great hunger, dug in, our whole body involved in savouring and enjoying every little ruby pearl without letting any drop.

It would be years later, when I had been away from Iran for some time, where the Persian pomegranate was a rare and expensive jewel, even then, not satisfying the palette fully with the taste of nostalgia, that I began to appreciate every little ruby drop, and associate its memory, its shape, texture, and colours with the homeland and the tradition that I had left behind,

And I was not alone. Many others, feeling the same nostalgia—a nostalgia beyond our current time—have, throughout thousands of years of history, also associated this fruit with an ancient Persian culture and the nuances that it carries. Rightly so, for this is one of the oldest and first fruit trees to have been domesticated since around 6000 BC, and its many seeds have made it a symbol of fertility, celebration, and continuation of the cycle of life.

In Iran, throughout recent history, the pomegranate, and its flowers, have had a prominent presence with numerous artists, writers, and designers, drawing inspiration from its form, colour, and texture to depict, maintain or critique important essences of our culture. This reference to the pomegranates as a marker of Iranian identity—amongst other motifs—has also spilled across the borders with the Iranian diaspora, carrying even more weight and urgency than in Iran.

This is why reference to the pomegranate is seen across numerous platforms of artistic expression by Iranians living abroad. It features, for example, prominently in the visual art works of Sara Rahbar, and Iranian-American installation artist living in New York. In a series of staged photographs addressing the conflicted issues of her Iranian-American identity, one marred by the continuous political tension and war, she depicts an Iranian woman (herself) wearing a white dress, and an American flag wrapped around her as a skirt, next to an Iranian looking man wearing an army uniform. The subjects both look deflected and worn out. Featuring in the background of her work, there is always a number of pomegranates, a reminder of the tradition left behind.

Susan Rahbar, #13 After You, A series of 24, Photography 2007, photo: Boback Ghourchian. For more examples, see website www.sararahbar.com

Many Iranian writers in English, too, draw on the image of the pomegranate to create fascinating and enticing titles such as Pomegranate Soup (Marsha Mehra), Pomegranate Sky (Louise Soraya Black), and Pomegranate and Roses (Ariana Bundy). In these titles, the reference to pomegranate not only carries with it nuances of a rich cultural tradition left behind for the writers, but it also gives readers a point of entry into the culture depicted.

While from a historical and aesthetic perspective, I understand the reasons why the pomegranate has become a symbolic fruit of the Persian culture, I also believe that there is another reason why it could be seen as the right fruit to draw upon to represent the Iranian identity and sentiment.

Contained tightly in the rough, dry and difficult to crack exterior of the pomegranate, unknown to many around the world, are hiding, sometimes bursting to come out, clusters of juicy, sweet and sour seeds.

To me, this is the epitome of the Iranian identity. Centuries of political, social, and religious forces have constructed a society where what’s public, seen and shared is significantly and surprisingly different to what’s unseen and held private. We have grown up in a world of interiors and exteriors, of walled houses, veiled women, and invisible barriers. Forced to abide to the rules of changing monarchies, governments and allegiances, we have had to learn to be law abiding citizens, reflecting and growing a tough exterior, changing shape to survive, while tightly holding onto, protecting and hiding our unchanging private essence and nature.

And now, for the first time, I was holding an actualized representation of this through Mehrnoosh’s unfolding pomegranate shaped Lotus Transporter. What makes this piece even more symbolic of the message it conveys is that when I opened it, it contained a secret hidden compartment revealed only if the centre of the piece is lifted up. A tiny little section, it is big enough for a few seeds of pomegranate, a space which Mehrnoosh describes is for carrying the wearer’s deepest secrets. A space where, one’s deepest sense of identity can be protected, like a pearl, encapsulated and intact, surrounded by the combination of the visceral forces of tradition and modernity that had led to its complicated construction.

- Mehrnoosh Ganji, Splendid sun, 2014, sterling silver, fine silver, 18 ct y gold, enamel, 50mm x 70mm x 20 mm

- Mehrnoosh Ganji, Splendid sun, 2014, sterling silver, fine silver, 18 ct y gold, enamel, 50mm x 70mm x 20 mm

Another object that was laid out on the table in front of me was Splendid Sun. It is a wearable piece that transforms from a bracelet to a pendent. As a bracelet, it is a six-sided star that is hinged together with a small lock and key. Inside each section of the six triangles that forms the stars are decorated with green and blue enamelled patterns, also in themselves playing with the six-sided star pattern. Although they look alike, each is slightly different.

This object transported my imagination to the patterns that I used to see throughout my childhood. Mehrnoosh told me that this piece has been in the making for years for her as well. When she was living in Iran, she would wander into the mosques in Isfahan and spend hours staring at the shapes and pondering on the geometrical patterns. Isfahan, is one of the oldest cities of Iran, without a doubt, one of the cradles of Persian culture and civilization. As a child, it was my dream to go to Isfahan. Seeing the patterns in the Splendid Sun, I was reminded of the first time I visited the city myself in my pre-teens. I will never forget the sense of awe and amazement that the myriad of patterns and shaped imprinted in my mind, the meanings of which I have only understood recently.

This pattern has a very deep meaning. It is a replication of the symbolic and sacred geometrical patterns of Islamic architecture. The philosophy of this shape originates from the desire to depict the harmony between the realms of heaven and earth. If we were to break down how the star shape is formed, it is made from the union of a circle and a square. The circle is the symbol of the heaven and the square the symbol of earth. The combination is the star form.

Constructed from the rough edges of the square and the roundness of the circle Splendid Sun, to me, is the ultimate representative of the Iranian identity, the combination of which forms this intricate and harmonious shape of the star.

To see this shape materialize like this, into a modern piece of jewellery, was a surprise for me. As a bracelet, this piece is extremely bold. The wearer would certainly be noticed for their bravery to carry this confidently on their body. But despite the boldness and its call for attention, to me it also conveys a sense of distance and inaccessibility. Each protruding side of the star sharply gives a sense of protection of the tiny green and blue patterns reflected from the inside. They are reflected, but they are untouchable and unreachable by others. Like the thick skin of the pomegranate, they are the parts of our tradition and heritage that we hold, reflected to the outside world, but yet protected by the exterior that guards it.

That the piece transforms by folding into itself for me is telling of our abilities to transform our identities and reflect them as we wish. By folding into itself to completely hide the star, this sacred shape—revealing a modern hexagonal form to be worn as a pendant—reflects our abilities to pick and choose how we want to be seen. The lock and key is symbolic of who has access to this dimension. While the patterns are now showing, juxtaposed onto the modern hexagon, the star made from the combination of heaven and earth, our deep secret identity, can be protected and hidden. What is chosen to show now is only the modern façade with touches of tradition exposed.

The title of the piece, Splendid Sun, was curious to me. In Iranian literature and art, the sun is usually a symbol of power and eternal presence. Unlike in other cultures, it is also, not depicted as round. The representation of the sun in Iranian traditional arts is usually like a star with different sides, flaring out from it, like the star depicted in Mehrnoosh’s piece. Like the sun that will rise, from the east to the west, our life will continue no matter how we perceive ourselves and our identities anywhere in the world and in whatever form, Iranian or Persian, we choose to take.

Of all of the pieces, the most interesting, for me, is the bracelet entitled Brick Spaceship. With straps that clasp like a watch, the object has a round disk with a purple gem in the centre with intricate gold threads that zigzag across it sharply to form a flower with many petals like a lotus. This disk opens. When I lifted it, I expected there to be a timepiece. Instead I saw a reflection of the patterns that formed the lotus on top carved out, but not as sharply and with more roundness, into the section below.

That there was not a timepiece, and instead a many petalled lotus, for me spoke volumes. Lotuses are symbols of eternity, renewal and rebirth, to me, they are the essence of timelessness. The lotus, hidden, where I was expecting a timepiece, was a reminder of timelessness. Timelessness not only of us and the shared human condition, but the timelessness of our continued attempt to make sense and grapple to find and define a sense of identity.

To me, the piece reflects another way we could view our identities—as timeless and spaceless, not as Iranian, Persian, or Australian, but as human beings connected to a larger timeless and spaceless network of infinite intelligence that governs our world beyond the limits of time and space constructed by the mind.

When we asked for the bill, the same waiter came back.

“Did you think about it?” I asked.

“Yes. But I don’t want to guess. I don’t want to offend you. Tell me, where you are from?”

Too bad we had to go. Instead of answering him, I wanted to take hold of Mehrnoosh’s pieces, open them up and say, “:=Let me show you…and tell you a story…”

But there was not enough time. Instead, like the Lotus Transporter that was now folded into a pomegranate around Mehrnoosh’s neck, I decided to hold the sense of mystery inside. I also could not tell him, “Planet earth” (without sounding rude or crazy) as I had wanted to reflect my meditation on the Brick Spaceship. So, instead, I took another form, “Australia.” I said.

He smiled. There was more question in his eyes, but we left, all of us, pondering.

Postscript

I was reminded of a video clip that I often watch by a modern Iranian singer, Aidin Joodi. In it a young man in western clothes is transported into a desert in search of his own sense of self. The song is a reflection of the complicated definition of our identities. Let me translate it for you:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLSSZico9lU

Reality is neither in color nor smell,

Nor in the sounds and notes,

Nor in this or that,

Neither in the wine nor the chalice.

I am neither the teacher nor the student,

Not the word or the message.

I am not hello or how are you,

Neither black nor white.

I am not what you say I am,

I am not what you want,

I am not the sky or the earth,

I am not chained to anyone’s definition or their slave.

I am not a mirage,

Nor am I a cup of wine for your lonely heart,

I am not enslaved,

nor am I sent from the above,

I am not knocking on any doors of bars, mosques, or prayer spaces,

I am not heaven or earth,

This is what I am made of.

I will tell you in secrets and whispers:

Until someone doesn’t hear these treasured words,

you will be how they define you.

You are the life of the world,

You don’t know,

That you are the point of love,

You are the garden of heaven.

I praise you,

who heard this message,

and didn’t fear and woke up,

so that you don’t settle for any broken down definition

and see nothing but the light in yourself

and connect to the flower of eternity.

You are not only a part of the whole,

you are the whole,

wake up!

More reading

The Iran/Persian opposition is not always as black and white as mentioned there. There are debates and studies about the various responses and effects of this type of literature that I didn’t have time to discuss. The study of diasporic Iranian writing in English has been the subject of many studies and scholarships over the last decade and half from across the globe. I have done an extensive study of the complexity of this body of work elsewhere. See my book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution. (IB. Tauris, London 2015)

Author

Sanaz Fotouhi is an Iranian-Australian writer, scholar, and filmmaker. She has a specific interest in diasporic and migrant literatures and arts. Currently, she is the assistant executive director of the Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. She is also one of the founding members of the Persian International Film Festival in Australia.

Sanaz Fotouhi is an Iranian-Australian writer, scholar, and filmmaker. She has a specific interest in diasporic and migrant literatures and arts. Currently, she is the assistant executive director of the Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. She is also one of the founding members of the Persian International Film Festival in Australia.