Welcome message:

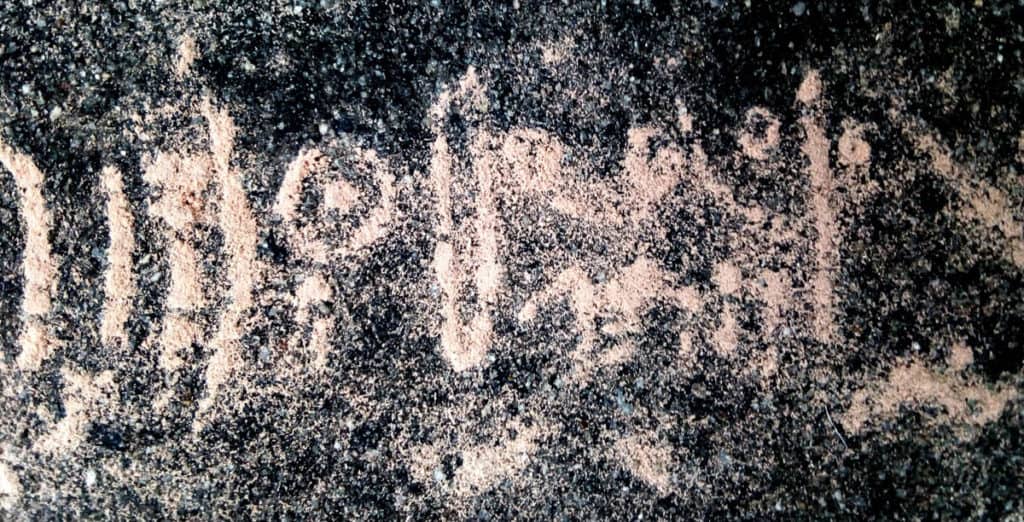

This serpent story was made by carving a boondi, or wooden club, although in my clan we would call it a yuk puuyngk, or law stick. I thought it was an appropriate medium for exploring the different laws of time and space for First and Second Peoples.

I studied the first and second laws of thermodynamics and yarned with elders and experts about these things (along with a bunch of old dead white guys), then stored that knowledge on my inner maps of the Great Dividing Range, which is the body of the Rainbow Serpent. It divides nothing, by the way, but connects systems along a massive song line. Parallel is the Great Barrier Reef, another serpent in carpet snake form, which is a barrier to nothing, by the way, but another infinitely connected story. Indigenous knowledge is kept in such song lines, so that’s where I stored that data, which I also carved into the club as a mnemonic to help me remember it.

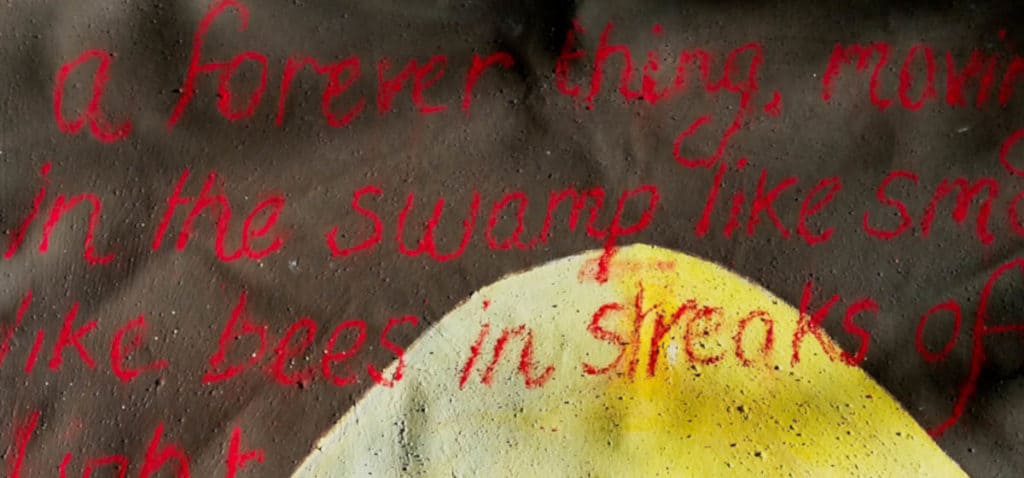

Around the head of the club, I etched an image of the Ouroboros to represent Second Peoples’ law and the second law of thermodynamics. But the three-dimensional nature of the club gives this two-dimensional image an additional layer of meaning, a truth that is revealed when you roll the stick across clay. An image appears of an endless procession of snakes, head to tail, representing the First Peoples’ law and the first law of thermodynamics.

First Peoples and Second Peoples seem to have a fundamental disagreement on the nature of reality and the basic laws of existence. It all comes back to notions of time, and the existential acrobatics required for Second Peoples to make time run in a straight line, to create a beginning, middle and end of things. First Peoples’ law says that nothing is created or destroyed because of the infinite and regenerative connections between systems. Therefore time is non-linear and regenerates creation in endless cycles. Second People’s law says that systems must be isolated and exist in a vacuum of individual creation, beginning in complexity but simplifying and breaking down until they meet their end. Therefore time is linear, because all things must have a beginning, middle and end.

Aristotle invented that idea, that sequence, which is ironically called the Growth Metaphor. For him, the end (telos) is the principle of every change. It is a strange kind of curse that demands an illusion of infinite growth while simultaneously insisting on inevitable decrease and annihilation. Second Peoples and their captives are required to believe wholeheartedly in this deception, in order to ignore the first law and experience time in a straight line.

We can’t blame Aristotle for this, however. The idea was present in northern cultures previously (if you adhere to a timeline view of history), in the form of a foundational civilising mythology of the Ouroboros. This was a metaphor representing infinity—a snake in a circle, eating its own tail. However, it contained the same curse, the same contradiction as the Growth Metaphor: how can this serpent be a symbol of infinity if it will eventually eat itself?

In the first law of thermodynamics, energy is neither created nor destroyed, it only changes and moves between systems. In the second law of thermodynamics, entropy or decay increases in a complex system as it inevitably breaks down, giving rise to what physicists call “the arrow of time”—but only in a closed system. Perhaps the desire to create closed systems and keep time going in a straight line is the reason for Second Peoples’ obsession with creating fences and walls, borders, great divides and great barriers. In reality, we do not inhabit closed systems, so why choose the second law of thermodynamics to create your model of time?

When we see that arc in the sky, that Rainbow Serpent, we are only seeing one part of it, and it is subjective, just for us. If we move the rainbow also moves, only appearing in relation to our standpoint. A man on the next hill will see it in a different position from where we are seeing it. The Serpent loves the water because that is what allows us to see him and he communicates with each of us this way, but he is not an entity of water. He is an entity of light. That doesn’t mean he isn’t dangerous. You have to wash any oil off your hands and mouth after eating if you go down to the water’s edge, or he’ll make you sick. He can take you up, if you’re lucky, but he can bring you down as well.

The part we are seeing there in the wet sky, or in the fine spray coming off the front of a speeding dinghy, is just a line across the edge of a sphere. Those spheres are infinitely overlapping, spiralling inwards and outwards, extending everywhere that light can go (or has gone or will go) and the Rainbow Serpent moves through this photo-fabric of creation. He goes under the ground too, but so does the sphere.

Ah, but is he a wave or a particle? I guess that depends on how you’re looking at him, but we would see him as a wave, a snake, because he is constantly in motion across systems that are constantly in motion and interwoven throughout everything that is, was and will be. There are infinite variations of him in all shapes and sizes throughout the world—wyrms, dragons, ureus and many different names in different regions, taking the shape of the spirit of those places. He was always there and always will be, unless people keep trying to make him eat his own tail.

I can’t see him properly though because I’m colour blind. Optometrists tell me this is because I’m not a “full-blood”. Apparently the blacker you are, the less likely you are to be colour blind. So I only see the Serpent as a vague, thin streak in the sky. However, it makes me look elsewhere for him, finding knowledge in unexpected places. My impairment also allows me to see the camouflaged snake in the grass that nobody else can spot on the ground in front of us as we walk and yarn, so it’s a useful impairment. Every viewpoint is useful and it takes a wide diversity of views for any group to navigate this universe safely, let alone to act as custodians for it. I stand in this gully and see him in one place, you stand on the hill and see him in another, and he gives us different messages that we are supposed to share with one another.

My subjective view of Rainbow Serpent helps me to perceive problems with the timelines we are all forced to inhabit today (although it also makes me miss appointments and write in logic sequences that are difficult for most people to follow). The “arrow of time” proposed by physicists is based on what happens to systems in a vacuum, but we don’t live in a vacuum. It works in lab experiments and is a real, observable phenomenon in closed systems. It is a true law. It’s just the wrong law to apply to beings living in open, interconnected systems.

This is an edited extract from Tyson Yunkaporta’s new book, Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, out through Text Publishing on 3 September 2019.

Author

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, an arts critic and a researcher who belongs to the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He carves traditional tools and weapons and also works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne.

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, an arts critic and a researcher who belongs to the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He carves traditional tools and weapons and also works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne.

Comments

Tyson brings Indigenous knowings across Western beliefs and makes it all very readable and exciting. Keep an eye out for his latest book, ‘Sand Talk’. It will have you walking through each day in a different, lively way.

Dear Tyson, Thank you for writing this book and article. I am a neurodiverse person and I see that thinking differently is a challenge to the self, not to change that thinking, but to find your own way that works with it. Sometimes that way does involve growth, which is change, but not forced. I struggle with time and intractable thoughts of the nature of light. I seek growth and I see in your words that I am not alone. I am grateful to know this. Thank you. You are a wonderful person.

Kindest regards,

Andrew (which means ‘manly’).