Elisa-Jane Carmichael, From then and now #5, 2018; Photo-Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery

Traditional techniques of woven fibre art are coming to the forefront of Australian art as Indigenous artists and communities across the country continue their twenty-first-century cultural renaissance. Weaving is very closely linked with storytelling in Indigenous cultures and even the now-common word for storytelling—yarning—resonates with the practice that pulls threads together.

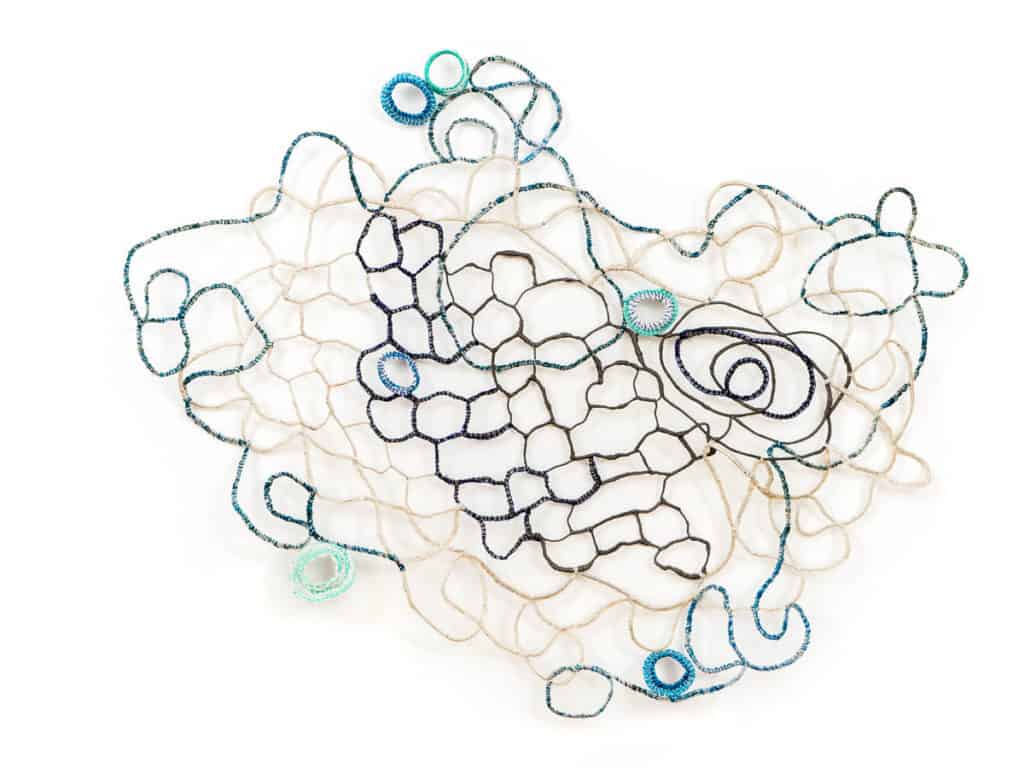

Elisa-Jane Carmichael, We see your hands weave with us, 2018, photo-Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery

Elisa-Jane Carmichael is one such artist who is making her mark in the art world with an extraordinary body of work that pulls many different cultural threads together. As a Quandamooka woman from the beautiful sand island of Minjerribah (Stradbroke Island), Elisa is attuned to the links with her ancestors and explores new methods and materials for expressing an intergenerational sense of what it means to be “saltwater people”.

I first met Elisa through her mother, Sonja Carmichael, who is a leading figure in retrieving a particular form of diagonal knotting unique to Quandamooka weaving. Sonja’s quest to “solve the knot” inspires her postgraduate research project at the University of Queensland, working with myself as an academic advisor. Many other Quandamooka artists are similarly translating their collective cultural renaissance into important academic projects based on Indigenous creative research.

Elisa’s own version of visual storytelling captures this renewal but also recalls the time of weaving’s absence. Traditional Quandamooka weaving techniques almost disappeared after the impact of colonisation and its incumbent cultural suppression and loss of homelands. The story of this loss and cultural reawakening sits over Elisa’s diverse art like an invisible web. Each creative piece is like a knot in the weave of her culture.

Her earlier art focused on translating traditional fibre techniques into wearable art but this has flourished into an oeuvre involving painting, woven objects and sculptures, and some poetry. A 2018 solo exhibition titled Will we swim together tomorrow through the Saltwater waves? is virtually one continuous conversation with ancestors writ large across space. Paintings are about weavings, weavings about stories, and stories about ancestors.

Elisa-Jane Carmichael, Time has passed and pieces are missing, 2018, photo-Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery

The woven wall sculpture titled Time has passed and pieces are missing is a signature piece in this regard. It is a basket adrift from its function as a carrying vessel. A gaping void in its centre seems to advance off the wall and act like a lens that penetrates through absence into presence. As we look into this void we can feel the woven world stirring, no longer sleeping. The story is then taken up in acrylic paintings such as From then and now #5. Elisa describes this image as telling the story of how, when she started to work with ungaire (Minjerribah’s freshwater swamp reeds), she called on ancestors to guide her towards the woven string used for guylai (women’s looped bags used to carry shells and food). The painting is composed of fragments of a weaving process that seem to float through time, like a snapshot of cultural memory.

We don’t often think of weaving as something that narrates history, but that is exactly what Elisa achieves with her recent free-standing woven sculptures. Her first was created whilst on an artist’s residency in the Central Australian desert. It was an initiative to help strengthen Saltwater people’s dialogue with desert cultures. Elisa was living outside town in a beautiful rural property framed by ruby coloured mountains. She loved the desert, but it also prompted her to miss Saltwater country at home. Elisa drew on this distance to create a piece that reflected all of her Saltwater experiences and techniques as a kind of composite of Quandamooka weaving.

Discarded wire found on the property was fashioned into a large cylindrical frame for the weaving, signalling how the desert was a catalyst for Saltwater memories. Elisa then wove ungaire fibres brought from home across the frame using string knotting and looping, coiling, and other techniques that were handed down by elders, taught by missionaries in the community, or part of the this generation’s new vocabulary of fibre art. The transparent column is now part of the University of Queensland’s Art Collection.

A similarly cylindrical large woven sculpture will be the centrepiece of Elisa’s exhibition at the 2019 Cairns Indigenous Art Fair. It is a collaboration with her mother and combines traditional ungaire with “ghostnet” marine debris fishing line, and delicately iridescent red emperor fish scales that are native to Minjerribah. These interwoven materials express the blends of people who form the Quandamooka community, and the fusion of past, present and future.

Large gaps in the fabric of the weaving again register the absences of cultural practices caused by colonisation. There is a strong sense of dialogue within the piece with the top half involving ghostnet fibres and the lower half woven from traditional fibres. The ghostnet panels include the recently reclaimed Quandamooka diagonal knot, whose presence mirrors the reclaimed land that was part of the Quandamooka successful Native Title claim of 2011.

Synthesis of Quandamooka’s cultural presence and historical absence again feature in the twenty baskets that accompany this piece. They incorporate more of the native pandanus leaves as fibres and each has the centre missing in acknowledgement of weaving reawakening from a long sleep. This latest work also signals a new development in Elisa’s concern to accentuate the individuality of weaving practices. The sculpture uses more embellishments of shells and decorative woven techniques to demonstrate how weaving expresses individual personalities at the same time as involving a collective Quandamooka culture. It is the new generation flowering in the footsteps of ancestors.

Elisa-Jane Carmichael, We see your hands weave with us, 2018, photo-Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery

Elisa-Jane Carmichael, From then and now #5, 2018_Photo-Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery

Sonja Carmichael + Elisa Jane Carmichael, Jalo Boma (after the burn) tears from the sea, 2019, photo-Louis Lim_6

Sonja Carmichael + Elisa Jane Carmichael, Jalo Boma (after the burn) tears from the sea, 2019, photo-Louis Lim

Elisa-Jane Carmichael, Alive (detail), 2018, photo-Louis Lim. Courtesy of the artist and Onespace Gallery

Author

Sally Butler is Associate Professor of art history at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. Her special areas of research and teaching include Indigenous art of the Australia Pacific region, and she is the current Guest Editor of a Special Issue of ARTS on Australian Aboriginal Art and Cultural Tourism

Sally Butler is Associate Professor of art history at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. Her special areas of research and teaching include Indigenous art of the Australia Pacific region, and she is the current Guest Editor of a Special Issue of ARTS on Australian Aboriginal Art and Cultural Tourism

Comments

They are gorgeous and I would like some. Where can I buy them