One European, the other Aztec. These pieces are united because Albrecht Dürer viewed the exhibition “The objects brought to the king from the new land of gold”, sponsored by Charles V. of Spain I. of Germany. Dürer wrote about seeing the show in Brussels with great admiration in an entry on his travel diary, the 27 of august, 1520. This is one of the few examples of European recognition of the Aztec treasures from an artistic perspective during the time. “Wing of a Roller” by Albrecht Dürer. (1512) Watercolor and gouache on vellum. 20 x 20 cm. Graphische Sammlung, Vienna. B.“Penacho” of the ancient Mexico. (ca.1545) Width 175 cm. Height 116 cm. (col. Ambras). Photo. 2010. Art History Museum, Vienna.

I have been working on a series of pieces that arise from a concern in contemporary practices with glass and with the material history in México. This has inspired me to explore about the significance of bright shimmering objects and its use in prehispanic times. What attracts me of this approach to materials was, how all objects made, map a conceptual and material landscape that is unique and describes its geography and cultural environment.

In order to have a broader, inclusive and contemporary view of glass locally (and globally), it is imperative to acknowledge that most of our ideas of value still derive from an established “colonial perspective”. Today, with recent archeological discoveries and most significantly with the development of material culture and postcolonial studies, we are capable of understanding a suppressed history of materials that was harder to discern before. In order to fathom this, we have to go way back to the shock of the conquest of the Americas, where great cultures where subverted, pushed aside and imposed into a new set of political and economic interests that transformed everything into stories of gold. The prevailing idea that indigenous people exchanged glass for gold, rested in a western optic that recorded this cultures along with their material values, in a condescending way.

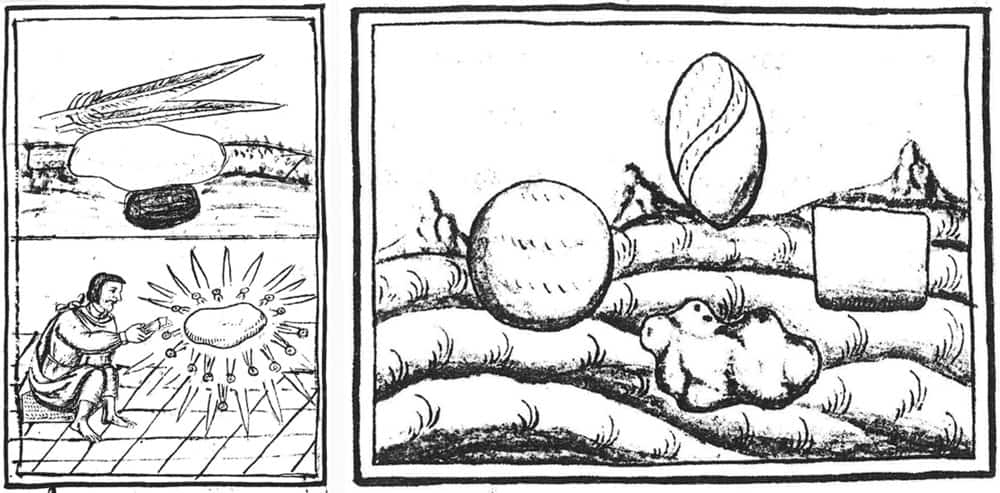

This collage made by the author of the text, it exemplifies the idea of the use of materials for the sake of movement and reflection of light. This are the eyes section of masks found in underworld, they where offerings displaying a range of colors and materials that respond to a sum of symbolisms still far from being understood, yet the eyes respond clearly to light, becoming alive with movement. In other cases we see a spiral drawn in the sclerotic symbolizing the same idea.

We now have to subvert again this idea of “naivetés” into the acknowledgement of an inclusive culture that respects “all things diverse”. For the Mexica[1], using a material to imitate or even substitute another was unconceivable because -each material accounts for its unique characteristics-. This way of thinking was immensely inclusive, and cherished diversity as a greater value. Through the study of Amerindian cultures, scholars like Nicholas J. Saunders[2] in Britain, along with many others, have uncovered how indigenous cultures conceived their material worlds in a wider context. Acknowledging an understanding of a multisensory place where objects dwell and move comfortably across space and through time, thus, integrating completely the physical and the spiritual aspects of life.

Amerindian craftsmen polished and devastated natural glasses. The interest in the material grew from their interest in brilliance, shimmer and from the belief that it represented the accumulation of creative powers that animated and regulated the universe.

They believed in the spiritual and creative power of light and how it embodied their society’s mythic identity.

Their raw material is mined from the earth and shaped by people, and, if we believe Ethno historical sources, they appear to give their owner access to the intangible world of reflections, where souls, spirits, and the immanent forces of the cosmos dwell (Baquedano, 2014, pp.6.).

Today it is hard to understand the difference between “ornament”, merely a decoration in comparison with “emblazonment” which is the use of an emblem. Our ancient world, had a very sophisticated language of elements and materials that made up a garment, a pyramid, or a ritual object, this included origins, attributes, form, color and meaning, all adding up to a newer level of context.

Materiality was “invested” with qualities abstracted from a cultural appraisal of the natural world. Their material culture objectified these qualities while combining them into something different, a sum of all. Every material accumulated qualities to conform a unique meaning.

That is why there was a wide variety of shinny and shimmering materials, metals and alloys where favored variously as they served as conveyors of sacred brilliance, opposed to the European´s interests where only gold, silver, pearls, and emeralds had any real (commercial) value.

As Nicholas J. Saunders has mentioned, the presence and use of this materials evoked an act of transformative creation by implying the trapping and converting of luminosity, in other words: recycling—“it also meant fertilizing the energy of light into brilliant solid forms via technological choices whose efficacy stemmed from a synergy of myth, ritual knowledge, and individual technical skill” [3].

The most appreciated characteristic of glassy objects was its reflection and the movement provoked by its glare. But other qualities, like those associated with the “Smoking Mirror,” where very much appreciated. Black mirrors made out of highly polished obsidian (volcanic glass) had a dark ephemeral reflection; these reflective devices were powerfully ambiguous because they shone with a “dark light.” They were connected with Tezcatlipoca “Lord of the Smoking Mirror”, one of the most intriguing and complex deities of the Mesoamerican world, associated with rulers, warriors, tricksters and sorcerers. The obsidian ( ytztli ), was considered a manifestation of Tezcatlipoca because of its semantic proximity, both where associated by materiality / invisibility and with its omniscience / omnipresence-[4]

The British Museum has one of this “Smoking Mirrors”, part of Dr. John Dee collection. Dr. Dee was an Elizabethan mathematician, astrologer and magician who had a deep interest in optics, “glasses” and in all the occult; he used this piece as a ‘shrew-stone’, a tool for his occult research.

In Aztec culture, iridescence was also considered a part of the sensory experience, and when expressed in movement it could speak more than objects themselves. This civilization left countless of objects that dialogued with space and light around them and in turn established a link with the Cosmos. Certainly not different from the way we use glass as an artistic medium today, these objects were also present in rites and ceremonies of daily life, therefore, they not only referred to creation, consumption and use, but also to a sense, an idea of continuous transformation and perception by those who watched or used them. <<The subjacent similarities between iridescence, light and reflection is expressed in materials like feather works, polished wood, burnished pottery, greenstones, obsidian, rock crystal, gemstones and a wide variety of shinny minerals and metals, also meteorological phenomenon, fire, water, natural mica[5], hematite, pearl of shell, pyrite, turquoise, jade, seeds, blood and semen>> [6], this last three materials where also symbols of fertilization and therefore of recycling.

It is clear that today many of these material objects have lost their connection with site specificity, cause and effect, and with ritual and movement in use. The same has happened to the work with craft. Today, we live in a time where the idea of art, and its making moves between the edge of new technologies and individualism, and the exclusivity of an artist, by the marketing of the “self”. We know more of the specific and less of the diverse. We forget how we used to “use and understand materiality”. We let ecosystems die, we let species disappear and substitute or forget them. With glass, we may be captivated by the thought of creating new techniques of working with it, but we seem to have lost interest in the ones appreciated before through other cultures and across time.In sum, what has motivated me to write this paper is to start a dialogue, and to put in the table some notions and concepts about a different sense of understanding past objects related to “glass” contextualize them and look into its value.

This collage made by the author of the text, collecting various examples of skulls made with natural glasses, carved and polished representing Mictlantecuhtli. I must say that some skulls represented here that are considered fakes, because they where made in the 1800 and where sold and traded in Europe. Others are neither pre-Hispanic nor fakes, but modern.

Further Reading

[1] Is a Nahuatl word pronounced [Mēxihcah], The Mexica are the Nahua people who founded Tenochtitlan and where rulers of the Valley of Mexico and other territories during the time of the arrival of Hernán Cortés. They are known today as the Aztec Empire.

[2] A British archaeoligist and anthropologist. Professor in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Bristol. Nicholas J. Saunders has investigated and published extensively on material cultures, aesthetics of brilliance, symbolism and colour in the landscapes of Mesoamerica, South America, and the Caribbean.

[3] Nicholas J. Saunders, “Stealers of Light, Traders in Brilliance: Amerindian Metaphysics in the Mirror of Conquest”, 1999: 246.

[4] Tezcatlipoca:Trickster and Supreme Deity. Editor: Elizabeth Baquedano. University of Colorado, Boulder, Texas. 2014 .University Press of Colorado

[5] For the Aztec, mica (metzcujtatl) was excreted by the moon, symbolized cosmic forces, and possessed a soft, buoyant light (Sahagún 1950-1978:Book 11:235).

[6] Nicholas J. Saunders, “Stealers of Light, Traders in Brilliance: Amerindian Metaphysics in the Mirror of Conquest”, Anthropology and Aesthetics, núm. 33, 1998: Published by the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, pp. 225-252.

Author

Valeria Florescano lives and works in Mexico City. Her former education as a graphic designer and being in a family of historians has been crucial to her development and work with glass since she first experimented with this material years ago. In 2010 she completed a MFA on sculpture at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (UNAM). Her goal is to show her artwork, travel and work in a wider international level in the future, and to devote to her studio “Fuego conJuego, Juego conFuego”, where she practices and projects concepts mostly blurring the limits between art, design and craft. If you are curious of her work please visit http://valeriaflorescano.weebly.com/.

Valeria Florescano lives and works in Mexico City. Her former education as a graphic designer and being in a family of historians has been crucial to her development and work with glass since she first experimented with this material years ago. In 2010 she completed a MFA on sculpture at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (UNAM). Her goal is to show her artwork, travel and work in a wider international level in the future, and to devote to her studio “Fuego conJuego, Juego conFuego”, where she practices and projects concepts mostly blurring the limits between art, design and craft. If you are curious of her work please visit http://valeriaflorescano.weebly.com/.

Comments

Valeria muchas felicidades, que interesante proceso…quiero mi calavera!