Sitting in Ah Xian’s Beijing apartment in late 2014, near the end of my first year of PhD study and third month in China, I became aware of a quality of ceramics now central to my research. This quality, dimly conceived at first, came into focus while we wandered Panjiayuan market later that day, as Ah Xian was searching for gemstones for his Evolutionaura busts and I for souvenirs to take home to Adelaide. Two decades earlier, Ai Weiwei had browsed these same stalls following his return to Beijing after twelve years in New York. He too was searching for souvenirs, not as mementoes of time overseas, but as aides-mémoires to breathe life into his distant memories of a changed city.

Nostalgia and the material anchors of memory were habitual preoccupations of that year in China, during which I looked back not only on Adelaide but also on England, my birthplace and childhood home. The recollection of this unearthing of roots, passage across the world, and navigation of gaps in knowledge, remembered or acquired, became another theme in my research. It inspired a fascination with artistic expressions of displacement in ceramics, the most global of media. For Ah Xian, Ai Weiwei and the other two artists whose works attracted my attention (Sin-ying Ho and Liu Jianhua) ceramics are vessels for remembrance of people and places past/passed. They bridge cultural and geographic divides and preserve a wealth of associations with past, present and future, safeguarding memories of self, home and nation.

Evolutionaura is a variation on a theme that has been central to Ah Xian’s work since 1998, when he began his most well-known project, China china (1998-2004), a series of over eighty porcelain busts of family and friends. His attraction to porcelain, or china—so intimately tied to the country of his birth that the two are synonymous in English-speaking contexts—grew from his desire for a medium more alluring than the plaster with which he had been working. In 1995, four years after seeking political asylum in Australia, he met Wu Yan, a young woman who had moved to Sydney from Jingdezhen, once China’s “Porcelain Capital”. Wu put him in touch with Jingdezhen-based scholar Zou Xiaosong and finally, in May 1996, Ah Xian travelled to the city himself. From this moment on, porcelain became much more for him than just an alternative to plaster.

Ah Xian, Evolutionaura1: Turquoise-1, 2011-13, bronze, gold, turquoise, 54 x 43 x 29.5 cm; collection and courtesy of the artist.

Before Ah Xian set foot in Jingdezhen, however, he returned to his childhood home in Beijing for the first time since leaving China. His mother had fallen ill, compelling a reunion tragically denied when visa complications delayed his arrival until two days after her death. When he travelled south to the Porcelain Capital, the frustration of a life divided between cultures must have been etched in his mind. Perhaps porcelain could bridge this divide, repair his fragmented memories of a home left behind and make whole a vision of China’s past that had become increasingly obscure. 1.Ah Xian, “Self-Exile of the Soul,” TAASA Review 8, no. 1 (1999): 7–8 The prevailing theme of his work from 1998 reflects this motivation: commemorations of family and friends, including those who accompanied him to Australia and those who stayed behind. Studying these portraits in Ah Xian’s apartment, where they sit on chairs, tables and cabinets, their features softened by a layer of Beijing’s ubiquitous dust, I realised that they’re not, as some have argued, morbid facsimiles. Like the clay from which they’re formed, they exude a reassuring physicality: creases and wrinkles of skin, undulations of muscle and contours of posture give flesh to the spectres of absent loved ones who haunt the memories of those who remain, standing guard against the threat of slow oblivion.

Ah Xian, China China: Bust 19, 1999, porcelain with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration, 28 x 40 x 20 cm; collection and courtesy of the artist.

Ai Weiwei’s turn to ceramics was also inspired by memories of home and family. Ai was born in Beijing in 1957, the same year his father Ai Qing (1910-96) was purged by apparatchiks for whom he had once written poems of praise. Ai and his family were forced into exile in Shihezi, in far northwest Xinjiang. Two decades later, they were at last permitted to return to the capital. Perhaps to escape the summer heat of the city, or give his father time to adjust, Ai Weiwei made a detour to Handan, in Hebei, spending three months in a ceramics factory where he created a series of sculptures that included his first published work: a small ceramic owl. He developed a fondness for ceramics long before this through his father’s treasured collection of souvenirs and gifts, amassed at the height of his fame as a state-sanctioned poet. From an early age, Ai learned the value of ceramics as fragile yet powerful vessels for fleeting memories.

While the circumstances of Ai’s first encounter with ceramics ensured that the intimacy of private recollection remained central to his use of the medium, it was their cultural resonance that took priority following his second return to Beijing, in 1993. His family’s homecoming had marked a watershed for Ai Qing, who soon reclaimed the literary authority he had enjoyed before 1957. Ai Weiwei, however, struggled to find his place in a city caught between the anxieties of the past and hope for a better future. After his brief foray into ceramics, Ai was among the first students at the reopened Beijing Film Academy and soon joined the Stars, pioneers of contemporary art in China. Yet his agitation persisted, and in 1981 he left Beijing in search of a new life in New York.

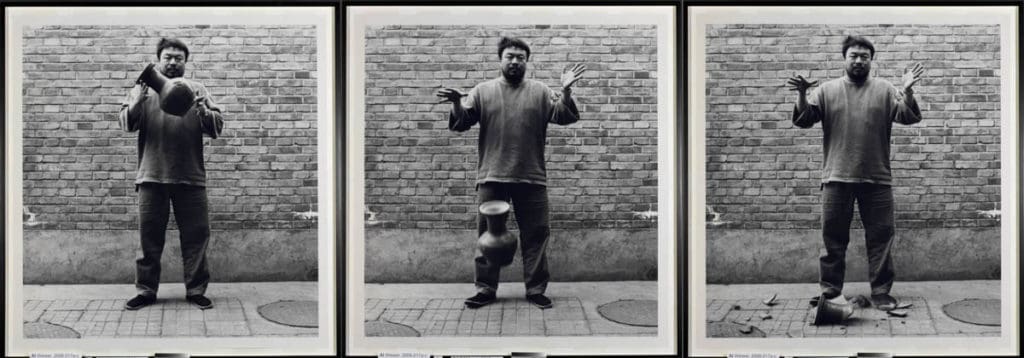

Like Ah Xian, Ai was ultimately drawn back to China by tragic circumstances, returning in 1993 to spend time with his ailing father. His return inspired a deeper engagement with ceramics, out of which some of his most iconic works emerged, including Dropping a Han-dynasty urn (1995). The changes in the physical and political landscape of China in his absence, mirrored by his father’s aging, illness and eventual death, inspired a renewed fascination with classical Chinese culture. Much of Ai’s time was spent with his brother, a ceramics connoisseur, searching Beijing’s markets for mementoes of long-forgotten dynasties. Reunited with a sibling-turned-mentor and a father who had once seemed capable of enduring the worst humiliation defeated by his own frail flesh, Ai found comfort in ceramics as a vessel for the origins of his personal and cultural identity. While Ah Xian has used the physical immediacy of clay to reunite friends and family separated by time and distance, Ai Weiwei transformed the same material into a vessel for a comparably estranged heritage just as fundamental and reassuring, just as immanent and essential.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han dynasty urn, 1995, gelatin silver photograph, three sheets: 180 x 169.5cm (each), purchased 2006. The Queensland Government’s Gallery of Modern Art Acquisitions Fund. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

Eight years after Ai Weiwei left New York, Sin-ying Ho arrived in the city to take up an Associate Professorship at Queens College. Her relocation was not inspired by a desire to find her place in the world but marked the culmination of a decade of academic study in ceramics that began with her departure from Hong Kong for Toronto in 1992. One thing she had come to share with Ai was a vision of ceramics as vessels for a heritage from which she felt isolated, even in Hong Kong. Sin-ying’s father, too, had been forced into exile: as the son of a landlord in Guangzhou, he realised the persecution he would face if he remained on the mainland after the founding of the People’s Republic and chose to seek asylum in the British-ruled New Territories. His flight became a crucial episode in Sin-ying’s self-mythology and a counterpoint for her own “return” to southern China in 1996, seeking the roots of her ancestral identity. Rather than Guangzhou, however, her passion for ceramics inspired Sin-ying to travel to Jingdezhen in neighbouring Jiangxi province, arriving just a few months after Ah Xian.

Sin-ying Ho, Identity (detail), 2001, porcelain with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration, digital decals, 28 x 30.5 cm; collection and courtesy of the artist.

Sin-ying first came to clay in the mid-1980s. Initially, she viewed it as little more than a pleasant diversion from her primary vocation: theatrical performance. It was only after moving to Toronto that ceramics gained meaning as vehicles of a Chineseness that seemed irretrievably distant in her own mind but, for those around her, defined the artist in straightforward terms. Arriving in the Porcelain Capital four years later, however, she realised the extent to which this identity had been complicated by her global passage, and even by the different forms of Chineseness to which she had grown accustomed in Hong Kong.

Rather than a prodigal daughter welcomed back with open arms, Sin-ying found herself greeted as a “foreign guest” defined by her affiliation as a student at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. She discovered that her memories of Hong Kong, while parallel to some extent with those of Jingdezhen’s residents, were not identical. The China she recalled was a cosmopolitan, quasi-independent city of six million, under British rule and so divided along cultural and linguistic lines. Jingdezhen, however, in 1996, could boast a population of just over one million, mostly speakers of the Gan dialect and workers in a ceramics industry suffering the effects of sudden privatisation.

Yet ceramics didn’t lose their appeal for Sin-ying and instead gained value as an ideal medium to express such dislocations, as attested by her first work in clay, Identity (2001). Emblazoned on the belly of this seemingly unremarkable jar, transfers of Sin-ying’s Hong Kong ID card, British National (Overseas) passport, Chinese travel visa, US Green Card and Canadian passport jostle with cobalt-blue motifs that, on closer inspection, dissolve into repetitions of her several names: Sin-ying Ho, 何善影, Cassandra. The quintessential blue-and-white vessel is thereby transformed into a vehicle for the global passage of the artist’s fragmented self, charting her movement across overlapping personal, cultural and geo-political dimensions of recollection and commemoration.

Liu Jianhua, Obsessive Memories, 1996-99, glazed porcelain, 51 x 44 x 31 cm; collection and courtesy of the artist.

While Sin-ying, Ai Weiwei and Ah Xian have found in ceramics a closer attachment to personal, ancestral and cultural memory, Liu Jianhua is distinguished by his efforts to distance himself from such ties. Paradoxically, he also boasts the longest relationship to clay, dating back to 1974, when he left home at the age of just twelve to apprentice with his uncle, a master ceramicist at one of Jingdezhen’s ten state-owned factories, where he remained until his resignation in 1985 to study at a local art school. Working on the assembly line with colleagues who had spent the last twenty years in the same place, each playing their part in the manufacture of an interminable lineage of identical porcelain products, Liu came to associate the medium with a lack of imagination, blind adherence to past models, and a numbing of creativity. Desperately seeking to extricate himself from this cycle, he abandoned ceramics in favour of more “artistic” media, seeking inspiration in the modernism of Auguste Rodin, Antoine Bourdelle, Aristide Maillol and Constantin Brancusi. His earliest exhibited pieces reflect these motivations: deliberately unfinished, atavistic totems of rough-hewn wood far removed from the pristine surfaces of factory porcelain. These archaic but vigorous forms reflect a mindset divided between a desire, on the one hand, to forget professional training and, on the other, a yearning to recall more primal sources of creativity.

Liu Jianhua, Life Series: The Erect Body, 1989, unglazed terracotta, 50 x 40 x 3 cm; collection and courtesy of the artist.

By 1999, Liu had come to terms with his past enough to return to porcelain for a series that pairs women’s bodies in brightly-coloured qipao with voluminous sofas and bathtubs. Like Ah Xian, he was drawn (back) to clay by his search for a medium more alluring, both visually and to the touch, than the fibreglass in which he had been working. Yet he also recognised its symbolic resonance as a distillation of cultural memory. The same could be said of the central motif in his first ceramic series, Obsessive memories (1998-2000), the qipao or cheongsam, a long, fitted dress closely tied to a certain era in Chinese history.

Qipao first gained popularity during the early decades of the twentieth century in the Republic that arose following the collapse of the Qing dynasty. Although inspired by women’s desire for equal political participation, they were appropriated by government propagandists as an expression of patriotic womanhood and national essence, like the kimono in Japan or sari in India. 2.Antonia Finnane, “What Should Chinese Women Wear? A National Problem,” Modern China 22, no. 2 (April 1996): 113–17. For Liu, qipao also conjured memories of his youth during the Cultural Revolution, when displays of sexuality and femininity were forcefully repressed and therefore gained, for Liu and other young men, an erotic fascination.3.Yuting Yan and Jianhua Liu, “«嬗变中的刘建华:艺术转变的内在逻辑 - 阎玉婷对话刘建华» [The Evolution of Liu Jianhua: Internal Logic for Art Transformation – Yan Yuting in Dialogue with Liu Jianhua],” Eastern Art, no. 3 (2009): 41. Obsessive memories evokes the power of memory to play on our desires, exposing the shared obsessions that fuse our most intimate fantasies with public narratives of national and cultural identity. Ceramics, as vessels for domestic ritual as well as nation-building myth, are an ideal vehicle for this exposé, though before Liu could excavate such symbolic residues, he first had to overcome the pressure they once exerted on him, when the weight of tradition had seemed a burden too great to bear.

Liu Jianhua, Games, 1999-2000, glazed porcelain, 56 x 56 x 9 cm; collection and courtesy of the artist.

In Garland’s first Quarterly Essay, published in 2015, Julie Ewington wrote of ceramics as vessels “for hiding in, for hiding secrets, for entering the unknown … [as] receptacles, not only for past histories and memories, but for our own present selves.” Although penned with South Australian artist Kirsten Coelho in mind, the relevance of these words can be extended to include a range of ceramic vessels, including works by Ah Xian, Ai Weiwei, Sin-ying Ho and Liu Jianhua. While they may not fit our usual, functionalist image of a vessel as a container intended to hold liquids, they conform perfectly to Ewington’s imaginative definition of the term. For each artist, it is the ability of ceramics to transport us across vast distances or to open a passage to the obscurities of the past that qualifies them as vessels for the safeguarding of memories that might otherwise be lost in their passage through time and space.

Author

Alex Burchmore is a Canberra-based art historian and arts writer. He recently received a doctorate in Chinese art history from the Australian National University’s Centre for Art History and Art Theory, where he works as a sessional lecturer alongside his duties as Publication Manager for Art Monthly Australasia. His PhD dissertation, soon to be adapted for publication as a book, focused on the use of porcelain by contemporary Chinese artists to communicate transcultural narratives of history and identity. In 2018, he received the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand’s annual award for “Best Scholarly Article in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art” and, in 2019, the inaugural “Oxford Art Journal Essay Prize for Early Career Researchers”.

Alex Burchmore is a Canberra-based art historian and arts writer. He recently received a doctorate in Chinese art history from the Australian National University’s Centre for Art History and Art Theory, where he works as a sessional lecturer alongside his duties as Publication Manager for Art Monthly Australasia. His PhD dissertation, soon to be adapted for publication as a book, focused on the use of porcelain by contemporary Chinese artists to communicate transcultural narratives of history and identity. In 2018, he received the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand’s annual award for “Best Scholarly Article in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art” and, in 2019, the inaugural “Oxford Art Journal Essay Prize for Early Career Researchers”.

Related stories

Tom Nicholson ✿ On repatriating an ancient mosaic

Elisa-Jane Carmichael ✿ Weaving with ancestors

Making clay precious in jewellery

Imagining a nostalgic future: The cosmic ceramics of Douglas Black

Ceramics Southern Africa: Down to earth connections

Touchstones:The sensual work of studio potter Jane Sawyer

References

| ↑1 | Ah Xian, “Self-Exile of the Soul,” TAASA Review 8, no. 1 (1999): 7–8 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Antonia Finnane, “What Should Chinese Women Wear? A National Problem,” Modern China 22, no. 2 (April 1996): 113–17. |

| ↑3 | Yuting Yan and Jianhua Liu, “«嬗变中的刘建华:艺术转变的内在逻辑 - 阎玉婷对话刘建华» [The Evolution of Liu Jianhua: Internal Logic for Art Transformation – Yan Yuting in Dialogue with Liu Jianhua],” Eastern Art, no. 3 (2009): 41. |

Comments

Most inspiring read. Lots to digest from a personal and creative journey in the context of a digital and global society.