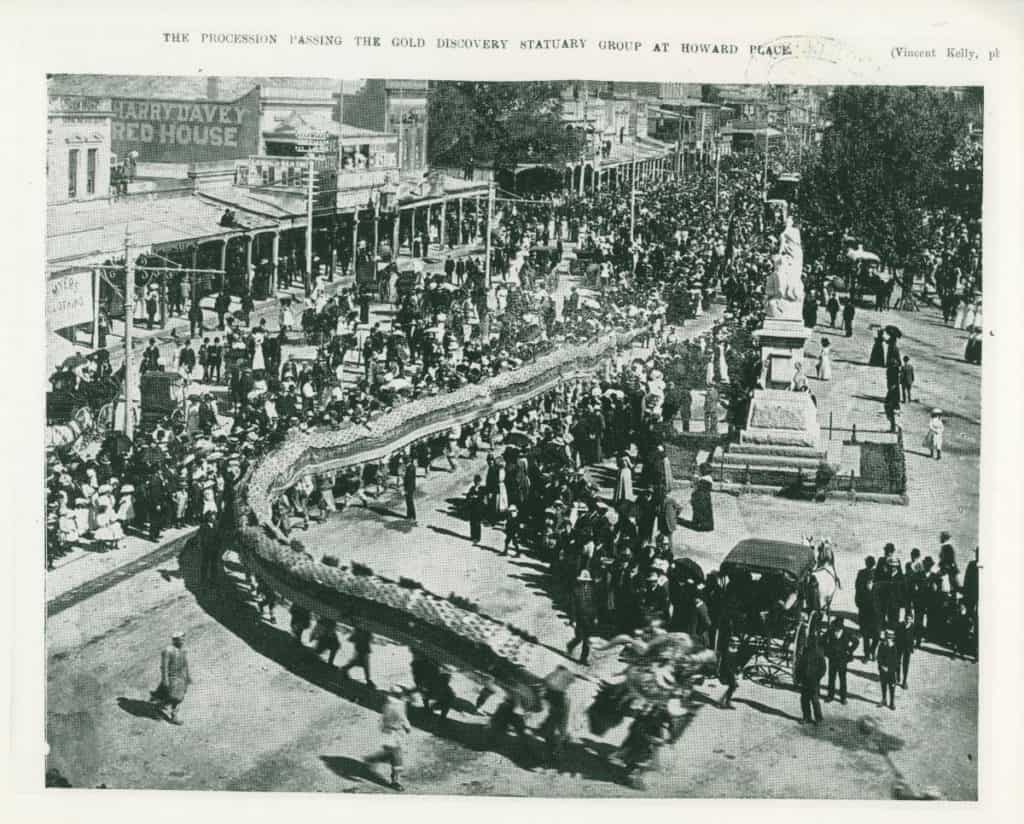

The dragon Loong in Bendigo’s Easter parade, 1911. (Collection Golden Dragon Museum. Photographer: Vincent Kelly)

The processional dragon collection at Bendigo’s Golden Dragon Museum has a breadth of styles and eras that seem to be unparalleled in the world – the late Qing dynasty Loong, pre-world War II Yar Loong, the night dragon; half a century old Sun Loong, and the brand new Dai Gum Loong, with several smaller dragons acquired over the past 27 years. The iconic dragons familiar to Bendigonians are large-headed, and long-bodied, with glittering mirrored scales, made in an opulent and imposing style that has its origins in old Canton, that is in the city of Guangzhou and its surrounding regions adjacent to the Pearl River Delta where so many miners and migrants had come from to the Australian goldfields.

The earliest dragon in Bendigo arrived in 1892 as a new star attraction in the city’s annual Easter Fair, an event in which the Chinese community had been participating since 1879 in order to raise funds for the Bendigo Hospital and the Benevolent Asylum.

Bendigo’s Sun Loong parading in the annual Easter procession, 1980s. (Collection Bendigo Chinese Association)

Dragon making is unfortunately not an official job description in the Chinese language (and neither is the literal title dragon maker)—rather the craftsmen who have made Bendigo’s dragons are said to be masters of za zuo, which can literally be translated as “tying work”, has been rendered as “ligation arts”, and which is commonly referred to in Hong Kong as paper craft. The basis of the head of a parade dragon is a skeletal frame of wicker or bamboo that has been carefully bent and then fastened into its final shape by paper ties. The frame is then covered with layers of material and other decorative elements that form the skin of the dragon’s face. Individually hand-made mirrored scales are attached to a cloth skin that is draped over the bamboo hoops that are both attached to the carriers’ poles and which also act as the ribcage or supportive skeleton of the dragon’s body. Coloured skirts hang below the scales, completing the body. A master of za zuo, of paper craft, might also be a maker of dancing lions, unicorns, and temporary ceremonial items.

When it became clear late last decade that Sun Loong, who had been made in 1969 by Hong Kong’s Lo On Kee workshop, would have to soon be retired from the parade, aside from raising funds for the project the pressing issue was also the possible lack of contemporary masters still capable of making old style Cantonese dragons. Modern social media proved helpful in finding and making connections with masters of the craft, and in June 2016 myself and Golden Dragon Museum general manager Anita Jack visited three men in Hong Kong who were reputed masters of the za zuo craft. By May 2018 it was decided to award the contract to Hui Ka Hung of the Hung C Lau workshop.

Hui Ka Hung and his assistants began work on the dragon in June 2018. The first task was making the around 7,000 mirrored scales. Layers of paper formed a base upon which the material pattern and decorative mirrors were stitched. From left to right a single oblong scale has the following features: a strip of white rabbit fur which borders the scale’s edge; a painted gold strip of the scales exposed paper base; a thin strip of green material with scalloped edging; an elongated red material strip bordered with gold thread and which runs back towards the right along the top and bottom edges of the scale and on top of which is stitched a series of small circular mirrors set in a metal mount; next within the compass of this elongated semicircular outer red strip is a strand of grey-blued patterned material; a layer of patterned gold coloured material follows next, and this borders a black coloured oblong section on which a similarly shaped brass mounted mirror is stitched. Each scale is, when removed as an individual piece, shaped like a sergeant’s chevron, and the central mirror echoes this with one rounded end and one pointed. The scales are then stitched together in horizontal rows which are sown onto a cloth “skin”—each preceding row slightly overlaps the one behind it, giving the dragon’s body the similitude of a real scaled creature. In the case of a Chinese dragon, the scales are meant to recall those of a fish, hence their glittering, shining, nature.

Mr Hui Snr stitches scales in his son’s workshop in Shau Kei Wan, Hong Kong, 2018. Photo credit: Billy Potts.

Work on the head began later in the year. Aesthetics, cultural tradition, artistic inspiration, and practical engineering all combine in the production of a traditional Cantonese dragon head. Master Hui had visited Bendigo earlier in 2018 to gain direct knowledge of and inspiration from Bendigo’s historic dragon and processional collection. Although the brief had been very particular about the scales, the head of the dragon was left to the maker’s personal creative choices. The making of the dragon head was carried out with a great deal of secrecy and images of its construction were embargoed on social media to ensure the surprise factor when he would eventually be unveiled. Master Hui chose to undertake a bold design in keeping with the dragon’s equally bold name, Dai Gum Loong, the Great Golden Dragon. Trimmed extensively with wool and rabbit fur, his multihued features glittering with small circular mirrors in brass casings, he has a striking and modern appearance that is combined with elements that are deeply traditional (such as the use of mirrors and fur trimming). The profusion of coloured silk pom poms are also traditional and come from the culture of Chinese opera—the presence of pom poms signals the importance and high status of a character on the stage and likewise advertises the regal status of a processional dragon.

Master Hui Ka Hung (right) and his nephew Hui Siu Kei apply the first layer of coloured cloth to the dragon’s head. Photo credit: Cheung Ho Lam

Master Hui puts the finishing touches to Dai Gum Loong’s head near the end of the project in January 2019. Photo credit: Cheung Ho Lam

Dai Gum Loong was designed to make an impression on the large stage that is the Easter parade at Bendigo. He made his debut processional appearance on Easter Sunday 21 April 2019. His 125-metre long body glittered with 100,000 mirrors distributed across the 7,000 handmade scales that decorate him from neck to tail. His 27 k.g head was carried for only 20 paces at a time by the team of specially selected head carriers who took in turns to help bring the dragon to life as he twisted and turned chasing after the carriers of the flaming pearl and the teaser in front of him – behind them over 60 body carriers acted as the dragons “legs”, bearing him along the length of the parade route on his maiden journey (they too had relief carriers on hand to take over the burden when needed). At the completion of the parade, Dai Gum Loong was backed in tail first into his permanent home in the Golden Dragon Museum’s main gallery, on a ramp which runs in a spiral around the inside of the building’s circular outer wall. There the Great Golden Dragon rests until next Easter when he will be reawakened, the latest dragon to continue a tradition unbroken in Bendigo since 1892.

Author

Leigh McKinnon is the research officer at the Golden Dragon Museum, Bendigo, Australia and is a research affiliate with the Centre for Religious Studies at Monash University. The Golden Dragon Museum is dedicated to conserving and interpreting Central Victoria’s rich Chinese heritage, and in his work at the museum Leigh has written publications on local historical themes, assisted in exhibition content, and provided advice and research support to people endeavouring to trace their Chinese-Australian family heritage. The museum’s processional collection, parts of which are still in use and which spans a time period ranging from the 1880s through to the present day, has been a particular area of interest for Leigh. His research work on the documented history and surviving examples of Qing Dynasty and 20th-century Cantonese processional dragons informed the brief for Bendigo’s newest parade dragon, Dai Gum Loong.

Leigh McKinnon is the research officer at the Golden Dragon Museum, Bendigo, Australia and is a research affiliate with the Centre for Religious Studies at Monash University. The Golden Dragon Museum is dedicated to conserving and interpreting Central Victoria’s rich Chinese heritage, and in his work at the museum Leigh has written publications on local historical themes, assisted in exhibition content, and provided advice and research support to people endeavouring to trace their Chinese-Australian family heritage. The museum’s processional collection, parts of which are still in use and which spans a time period ranging from the 1880s through to the present day, has been a particular area of interest for Leigh. His research work on the documented history and surviving examples of Qing Dynasty and 20th-century Cantonese processional dragons informed the brief for Bendigo’s newest parade dragon, Dai Gum Loong.