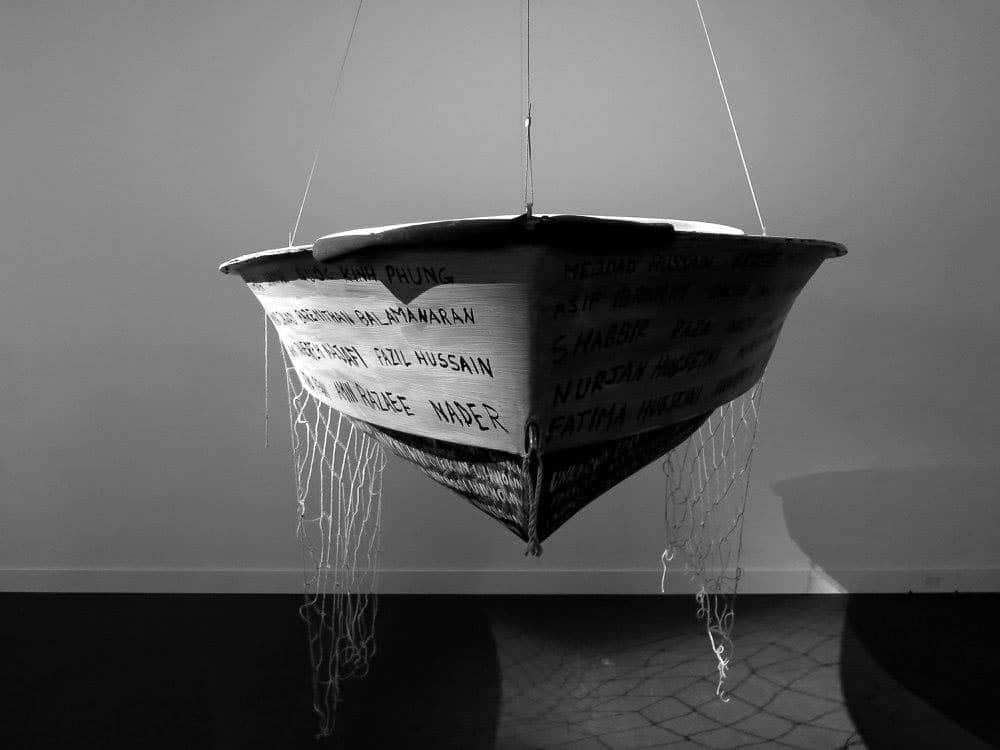

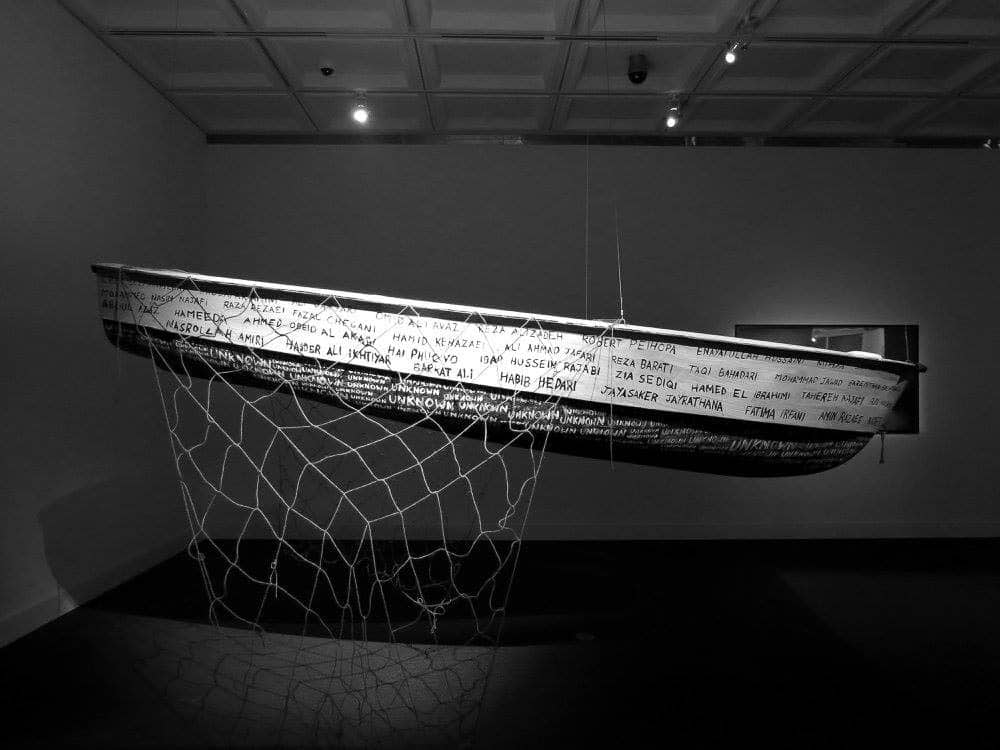

Call Them Home is a mixed-media installation piece I made in 2016 as a memorial to those who have died while seeking asylum, be it on the way to Australia, within the detention centres, or as a result of the trauma endured through Australia’s asylum seeker processing program. The work consists of a fibreglass boat with hand-woven fishing nets made from twine draped over it, suspended from the ceiling of a gallery.

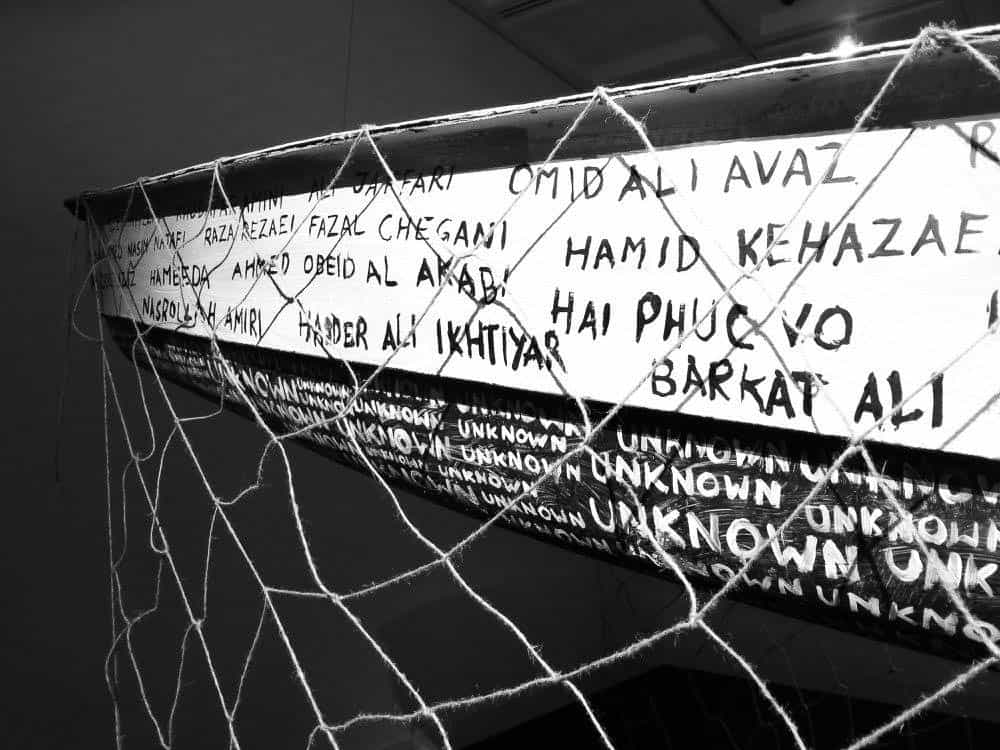

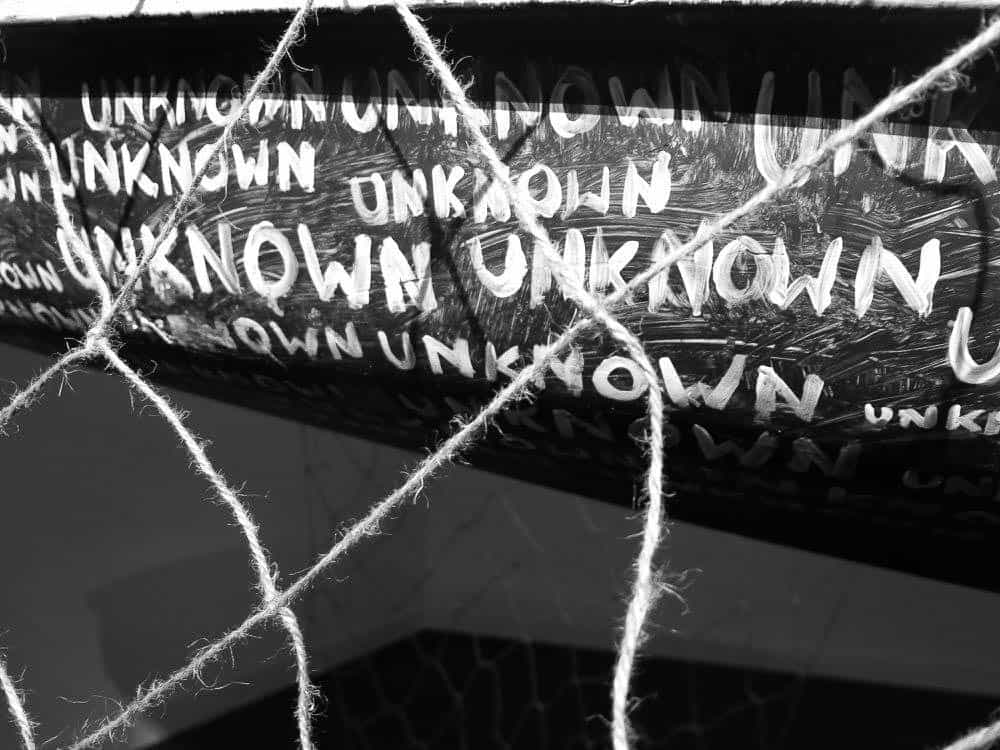

The boat is painted with names of people who have died either making the journey to Australia or in detention, with multiple “unknowns” below the waterline to indicate the people who were lost to the ocean, without any record of themselves of their identities.

The work came about as the entanglement of many ideas and experiences. My own parents fled during the war when Bangladesh seceded from Pakistan, leaving in the middle of the night on boats that took them around the tip of India to modern day Pakistan. While their experience is very different from what people are facing today, the reality remains that my existence is down to a combination of circumstances including that my parents, separately, sought refuge by boat. As such, the idea of displacement and asylum is one that is woven into my identity and reflects in the creative work that I do.

In Australian detention centres, it is a recorded practice that people are referred to by their boat numbers. Each maritime arrival is given a designation: a 3–letter prefix to stand for the boat, followed by 3 numbers to indicate the order in which they disembarked from the boat. Stripping asylum seekers of their identities and referring to them as boat numbers is one of the myriads of ways that the asylum seeker processing program dehumanises people. The piece seeks to subvert this, in allowing the boat to carry the names of the very real people who lived—and died—while reaching out to Australia for help.

Each one of the names carries a story. Some of these stories are known—Reza Barati, for example, was the first person killed in the Manus Island detention centre in February 2014, and his death was reported in mainstream media in Australia. Others, such as Meqdad Hussain’s story narrated by his nephew, are lost to the world, only remembered by family members who survived the journey to Australia and subsequent experiences in detention.

And what of the unknowns? There are countless ones. Available records indicate nearly 2000 deaths at sea of asylum seekers attempting to reach Australia by boat. These numbers are approximate, gleaned from first-hand accounts and media reporting of incidents, but conversations with asylum seekers reveal that there are many more boats that simply vanished, presumed lost and all on board drowned, that have never been officially recorded.

The fishing nets, made with twine and draped over the sides of the boat, tell another story: that of the fishermen turned people smugglers due to the impact on their livelihoods from overfishing and legislation. They too have a story to tell, as many of them are forced to seek out alternative means of livelihood when faced with the collapse of family trades. They too face detention, with Australia infamously jailing minors in adult prisons or holding them in the centres with adult men. Their stories are tied up with the experiences of asylum seekers, woven and knotted like the twine that trails from the boat but ultimately, they are viewed differently: sometimes as profit merchants, other times as unwilling participants in a system that they are unable to walk away from.

The work was first displayed as part of the Here&Now16/GenYM exhibition at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in Perth. On the day of the exhibition opening, news came through of another death, this time of Omid Masoumali, an asylum seeker who self-immolated in desperation at the regional processing centre in Nauru. As the artwork was already installed, at the time it was not permitted to be changed and updated in order to include the most recent name. In response, a group of activists instead staged a silent protest, standing in front of the work with their arms and crossed above their heads, wearing t-shirts with the name “OMID” on them.

Since that first display, there have been 14 more deaths, either in detention or in the community. The majority of these deaths have been ruled as, or are suspected to be suicide. Psychological trauma has been cited as a key factor in a number of these deaths. The installation is a living piece, recording these deaths as well, reflecting and memorialising and serving as a visible reminder of the very real impact of Australia’s asylum seeker policies.

(Records of deaths taken from the Australian Border Deaths Database as well as from individual accounts from asylum seekers)

Author

Marziya Mohammedali is a wordsmith, photographer, designer and artist based in Perth, Western Australia. Her practice focuses on narratives of dissent, identity, migration and transition, working for social justice through multidisciplinary creative practice. She is the Creative Director of Jalada – A pan-African writing collective and has exhibited her work internationally.

Marziya Mohammedali is a wordsmith, photographer, designer and artist based in Perth, Western Australia. Her practice focuses on narratives of dissent, identity, migration and transition, working for social justice through multidisciplinary creative practice. She is the Creative Director of Jalada – A pan-African writing collective and has exhibited her work internationally.