Carried Away: Bags Unpacked, Exhibition Entrance, 2019, Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira; photo: Max Lemesh

Held close to the body, whether slung askew across a shoulder or closely strapped to the back, bags are objects that have the ability to disappear right under our noses.

Ubiquitous, they can blend into the background, becoming the backdrop to the items they carry. Carried Away: Bags Unpacked is an exhibition that shines a light on bags themselves, showcasing 155 bags from the collection of Auckland Museum.

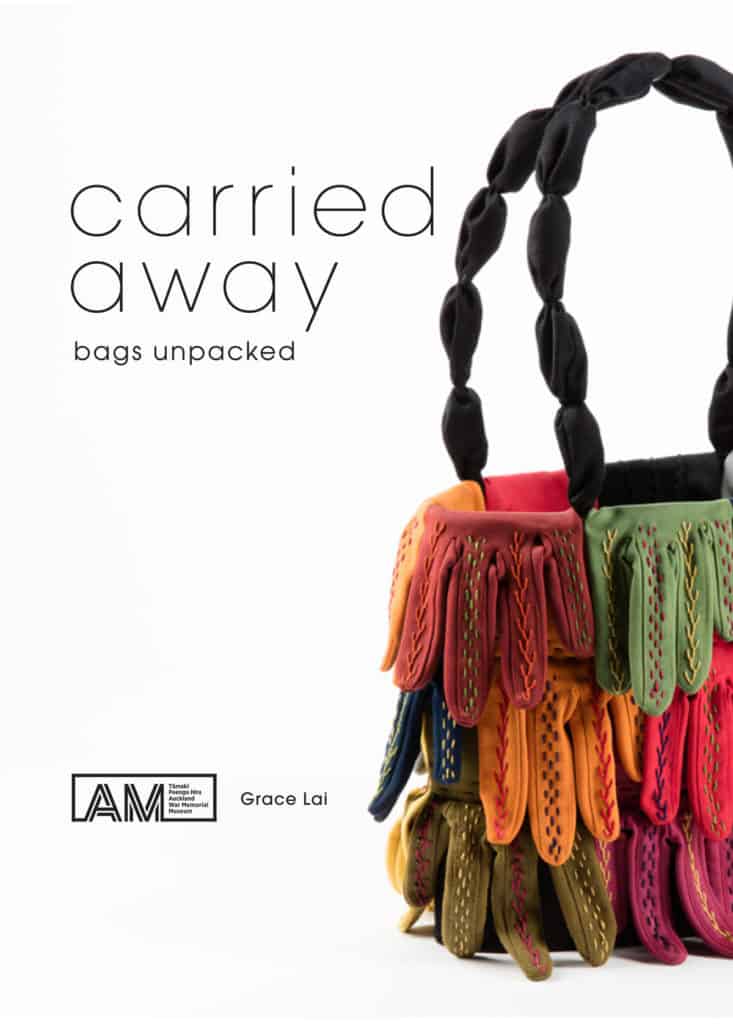

Carried Away: Bags Unpacked, Publication, 2019, Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, photo: Max Lemesh

Bags include the enchantedly beaded to the rustically constructed, ones made from bull kelp to ones blown from glass—it is a visual delight. The range in forms signals the diversity of a common object. It hints at the different function and meaning bags can carry, across culture and time, that bags carry more than just physical items, they can convey stories of the individual and the collective. In order to capture some of the rich histories, the exhibition where possible includes extended object labels, as well as, an accompanying book of the same name. The publication inspects the essential qualities of an object that comes to inform its identity and onto which society attributes ever-changing meaning and values. As always, there are more stories than word count allows. The following is one chosen from the cutting room floor that explores the rich web of connections tied to a rather unassuming bag that is on display.

Sanitary Pad Bag, 1950s, plastic and cotton, 160 mm x 380 mm. Collection of Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, 1996.180.19.

Crinkly plastic coloured milky green, much like the palette of mint toothpaste, and overlaid with an off-white floral motif is folded into an accordion pleat. Sewn shut at one end and edged by yellowing lace trim on the other where two cotton ties are attached, functioning as fastenings. Why this fabric? Why this pattern? The combination of kitsch design and simple construction are hardly elements that inspire poetry. Yet what this plastic bag lacks in presence, it counters with the rich and complex history it is embroiled within. Made in the 1950s, likely in New Zealand, the bag is made to hold sanitary products. While the purpose is singular and straightforward, a different picture is painted when a wider historic context is taken into consideration.

The disposal of feminine products after use is probably not something that is at the forefront of most minds. In New Zealand, modern public toilets are expected to be equipped with a sanitary bin, tucked in the corner of every cubical, easily accessed. However, this was not a luxury for women in the past. Women’s rights, unfortunately, did not reach the private space of the bathroom. The invention of manufactured products that specifically cater to the Time of Month was only commercially available since 1888. Although, this released women visited by their monthly friend from having to wash their home-made towels, yet, their disposal was not considered for some time after.

Prior to the Second World War many public places in New Zealand, like schools and the workplace, did not consider the need for sanitary waste disposal. Even when the absence of disposal facilities was addressed, initially, no thought was given to the placement of disposable units so that they were accessible. Barbara Brookes & Margaret Tennant’s research revealed multiple recollections of the ordeal women in New Zealand faced during Moon Time. Janet Frame recalled walking with, “soiled sanitary towel in hand for all to see, from the lavatory, across the tiled echoing floor, to the incinerator at the far end of the room.” Despite their availability, many women during this time still felt more comfortable to carry their used sanitary products until they got home to discard them.

This situation was magnified when taken outdoors. A 1996 report carried out by Pip Lynch, commissioned by the Department of Conservation of New Zealand, underscores the lack of information regarding the management of menstrual waste outside. The document concludes that the most hygienic and green method was to encourage women, who had the painter’s in, to use the “carry-home” bags provided by DoC. This came with the suggestion that the bags could be available in dark colours with air-tight closures to facilitate products coded red to be carried home.

Knowing the context in which the plastic sleeve was made transforms the rather unassuming bag into an essential tool for women. It facilitated and concealed their Lady Business, particularly useful in the event of wearing a pocket-less dress. The need for camouflage reflected a time when a sense of shame was associated with a natural biological function. Peppered throughout the article are euphemisms associated with menstruation (see if you can spot them all) that reinforces the stigma of menstruation as something taboo. Some of these terms are still used today, just like the cousins of this sanitary bag continue to exist, albeit in different forms and have altered functions. Although the disposal of sanitary waste is no longer a pressing issue, menstruation and their associated products are still not fully welcomed, nor embraced, in the open. Instead, they are generally confined to the shadows of a pouch or pocket.

Here the everyday object, the sanitary bag, unroots the social issues of gender inequality that framed its creation, illustrating that it is a concern that continues to have agency today.

Carried Away: Bags Unpacked 13 July – 1 December 2019, Auckland War Memorial Museum New Zealand

Further reading

Grace Lai. (2019) Carried Away: Bags Unpacked. Auckland: Allen and Unwin.

Barbara Brookes & Margaret Tennant. “Making Girls Modern: Pakeha Women and Menstruation in New Zealand, 1930-70.” In Women’s History Review, 7:4 (1998), 565-581.

Pip Lynch. “Menstrual Waste in the Backcountry.” In Science for Conservation, 33. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand (1996).

Author

Guided by a curiosity for the stories told by objects that are overlooked or dismissed, Grace Lai, is interested in seeking out the webs of connections between material and immaterial culture. This philosophy was developed during her time as an Alphawood Scholar at SOAS University of London. Today, Grace is an art historian and curator at Auckland Museum, where she leads the exhibition, curation, and development of the Applied Arts and Design Collection. Currently, her research is focused on expanding the collection and discourse of contemporary New Zealand practitioners, which has seen her get carried away by bags.

Guided by a curiosity for the stories told by objects that are overlooked or dismissed, Grace Lai, is interested in seeking out the webs of connections between material and immaterial culture. This philosophy was developed during her time as an Alphawood Scholar at SOAS University of London. Today, Grace is an art historian and curator at Auckland Museum, where she leads the exhibition, curation, and development of the Applied Arts and Design Collection. Currently, her research is focused on expanding the collection and discourse of contemporary New Zealand practitioners, which has seen her get carried away by bags.