Lured by the smell of Turkish coffee, Jacqueline Stojanović discovers the home of Serbia’s Pirot heritage carpet

Boiled Turkish coffee stings me with nostalgia, the recurring sensation that punctuates my social world, my work, and one that reminds me of the changed and changing parameters in which we occupy. Made at home on the stovetop flame in an enamelled steel pot, the method forces the cooker to remain on the side, watching and waiting attentively until the coffee ground begins to boil to the top. Wait too long, or become distracted, and it will boil over. A mess.

It’s called Turkish coffee in my kitchen, but it’s also known as Lebanese coffee, Armenian coffee, Ethiopian coffee, Greek coffee, Bosnian coffee, Serbian coffee—or domača kafa—in many others. I’ve often thought of it as one of those fraught cultural symbols imperceptibly tracing shifts and movements of people and territories over time. Whose was it initially? Whose is it now? I liken that line of enquiry to carpet making. In 2016 I was introduced to hand weaving. Having been given a small children’s loom only big enough to create tapestries measuring 20 x 15 cm, I began to create small-scale woven panels. I was immersed in the joy of experimenting with various warp and weft yarns and creating my own patterns. This pleasure in creating such pictures made of wool eventually led me on a personal research journey to try to understand the history of carpet weaving more broadly. From something so small I wanted to understand how larger flat woven pieces could be and have been created.

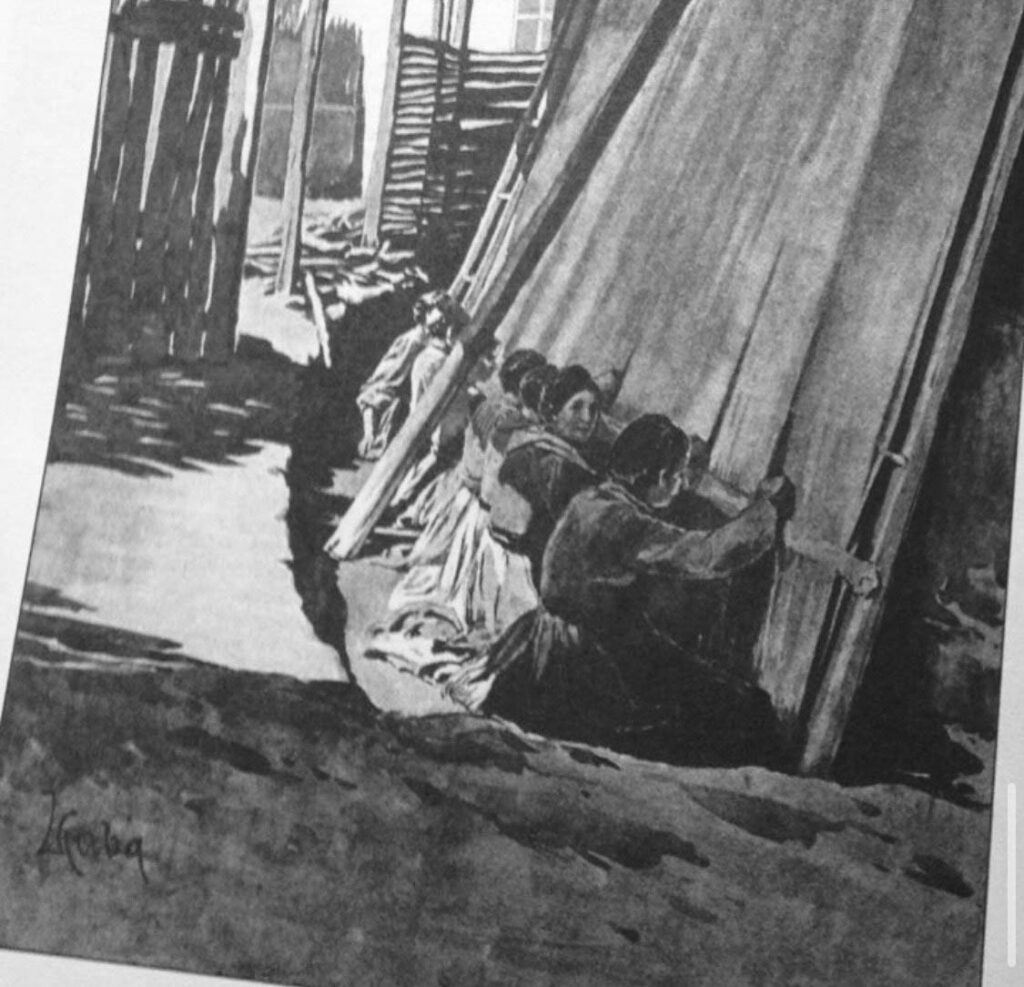

- Pirot weavers, WikiCommons

- Ludvik Kuba, Weaving carpets in Pirot, Drawing, 1896

In the spring of the same year, I fortuitously received an invitation from a friend who was working in Armenia. It was an invitation to come to stay with him in the small town of Arteni bordering Turkey. He explained to me that Armenia is the place where the world’s oldest surviving carpet is believed to have been created, the Pyrazyk Rug. With little hesitation, I booked a plane ticket to Yerevan, the country’s capital, where I arrived a few months later. My time in the Caucasus was rich in impressions and, as expected, only deepened my intrigue in the production of carpets throughout the region. I eventually extended my curiosity and explored areas of Iran, Turkey and Bulgaria overland, impressed to learn of the degrees of difference in the varying techniques practised and technologies developed by weavers, and the end uses for carpets in each place.

Eventually, winter came around and I was due to arrive in Serbia, where my relatives were expecting me for Christmas and the winter holiday season. Upon my journey to meet them in Belgrade, I passed through the southeastern city of Pirot, and there I was looking forward to meeting a community of weavers who continue to practice carpet making, the traditional Pirotski čilim.

The city of Pirot is renowned for these traditional carpets, which are created in a flat woven style on an upright tapestry loom. Bold in colour and unique in their geometric arrangements, the symbols of the carpets are significant to the country and represent the everyday world around the people who live on it, symbols like the dragon, the turtle, the cross, and more recently, the bombe (bombs). Behind an alleyway of the city’s industrial centre, I visited the small weaving workshop of Pirot called Damsko Srce, a co-operative whose name can be translated as Lady’s Heart.

- Čilim weavers, Damsko Srce, Pirot, 2016

- Čilim weavers, Damsko Srce, Pirot, 2017

I entered and it smelt like coffee, Turkish coffee.

As the co-op’s name suggests, the carpets are typically produced by women, who have inherited their carpet-making skills from the generations before them. Slavica Cirić, the Director of Damsko Srce, greeted me warmly. She was enthused to describe the co-op’s activity to a young Serbo-Australian woman traversing continents specifically for woven knowledge. From loom to loom, I followed her as she explained to me the labour-intensive processes involved to create a true Pirot carpet, with Damsko Srce being the sole authorised user of the geographical indication (GI) “Pirotski čilim”.

The sound of the weavers’ fingers plucking warp threads and beating their piles created a strange rhythm within the studio. It is a small room with upright looms evenly spanning the perimeter, the walls a pale shade of lilac. The focal point at the far end wall of their workspace is an impressive Pirot carpet measuring roughly 2 x 4 m. The design of the carpet was familiar yet distinctive. It brought to my mind visual memories from weavers’ studios in Armenia, Turkey, and Bulgaria: places not too far away in distance or memory. I learnt that the concentric motifs are ancient forms, and echo those seen on Egyptian ceramics and Cyprian vases, reflecting the older influences which have shaped the carpet-making tradition through centuries. The organised manufacture and official co-operative of čilim weavers in Pirot was founded 122 years ago, but the practice of čilim weaving in Pirot more generally dates back to the Middle Ages.

While the carpets remain an important symbol of Serbian folk tradition they take strenuous time and effort to complete. On average, a weaver at Damsko Srce works 176 hours to weave just 0.8 square metres of a carpet, an astounding amount of time spent concentrated at the loom. But what surprised me moreover, was that there were just ten women active while I was there. This figure greatly impacted me, since as recently as 1965, over 1,800 women lived and weaved in Pirot. This sudden decline in the cultural practice is a result of migration, rural exodus, economic instability, and brain drain across the inter and post-war years of the country.

The symbolism of each carpet’s motifs is now generally remembered by an older generation. These days it is found less in the contemporary homes of Belgrade. Additionally, with strict rules to ensure quality standards, the warp threads of the carpets are made from the white wool of the pramenka breed of sheep that graze the mountains surrounding Pirot, which is now unfortunately an endangered species. Given the decline in the current daily practice of weaving there, the carpets are recognised as UNESCO cultural heritage artefacts. Protective as it seemed, I couldn’t help but wonder whether such an accreditation might limit their market growth, with their display most likely seen in the contexts of the antique store, dignitaries’ offices, and the ethnographic museum.

I didn’t know whether to call the coffee Turkish anymore.

The time spent in Pirot imbued me with new curiosities about those shifts in cultural values, practices and displays. I lamented deeply how quickly knowledge can become lost, but was ultimately grateful to have encountered those ten women who were keeping a tradition alive, hands and hearts weaving beautiful carpets together.

About Jacqueline Stojanović

Jacqueline Stojanović lives and works in Naarm/Melbourne. She is a visual artist, weaver and educator engaged with an expanded textile practice that considers histories of the handmade through the processes of weaving, drawing, assemblage, and installation. Taking the position that weaving is an ancient carrier of culture, Stojanović explores past and present personal cultural narratives; adopting the language of abstraction and approaching weaving through an open use of materials from the industrial to the domestic. She is currently based in Prato, Italy, as the artist in residence at Lottozero: Centre for textile design, art and culture, where she is developing a new body of work for upcoming exhibitions in 2023. Visit www.jacquelinestojanovic.com and follow @malarugs.

Jacqueline Stojanović lives and works in Naarm/Melbourne. She is a visual artist, weaver and educator engaged with an expanded textile practice that considers histories of the handmade through the processes of weaving, drawing, assemblage, and installation. Taking the position that weaving is an ancient carrier of culture, Stojanović explores past and present personal cultural narratives; adopting the language of abstraction and approaching weaving through an open use of materials from the industrial to the domestic. She is currently based in Prato, Italy, as the artist in residence at Lottozero: Centre for textile design, art and culture, where she is developing a new body of work for upcoming exhibitions in 2023. Visit www.jacquelinestojanovic.com and follow @malarugs.