Michael Winkler is impressed by the resilience in the USA, embodied in those who continue to work with iron.

(A message to the reader.)

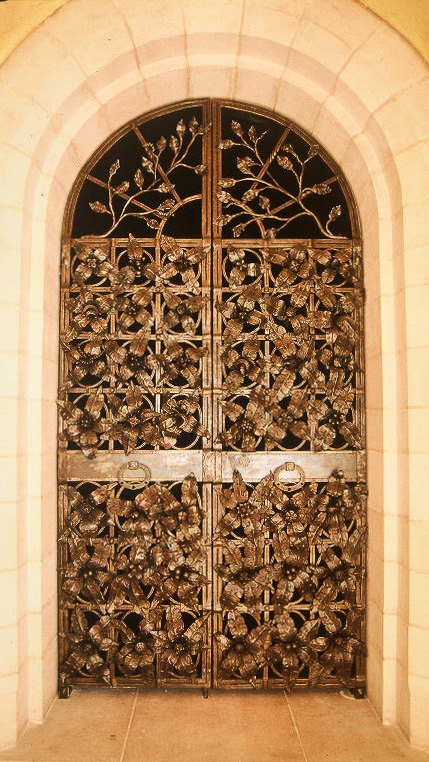

The Folger Gate

Washington DC’s National Cathedral is the sixth-largest cathedral in the world. It perches on the tallest hill in the north-west section of the city, and its spire is the highest point in the national capital. It is Episcopalian but emphasises ecumenism. In a country where church design tends to be quotidian, the National Cathedral is unflinchingly Gothic. This is where the funerals for four US Presidents have been held, and where five of the past six Presidents prayed on the day of their inauguration. It has become the USA’s most important place of worship.

Descend to crypt level and you enter a vaulted space delineated by huge columns that support the piers in the crossing of the nave above. The Chapel of St. Joseph of Arimathea leads to a columbarium which has niches for urns as well as burial vaults. There are three metal gates, designed and made by blacksmith Nol Putnam. All are remarkable, but one stands out.

The Folger Gate was completed in 1993 and installed at the West Columbarium in 1994. It is almost two-and-a-half metres high, weighs 545 kilograms and took 1200 hours to create. It has a design sufficiently bold to confer consequence when viewed from a distance, and innumerable small embellishments to reward close inspection. It is covered in 204 iron leaves and 42 flowers. Every petal and pistil is different. Each rivet head has been incised with an individual design, to catch light and imagination. The grid of densely clustered flowers resolves upwards into a sparse, graceful arrangement of branches in the lunette. Magnificent.

Out of Australia

As a child in rural Australia, I knew about blacksmithing because it appeared sporadically in books, usually as shorthand for virulent manhood. Most of the farms I visited had anvils tucked in dusty workshop corners, and presumably there were farriers who shod horses, but I did not see anyone working hot metal. The only childhood recollection I have of seeing a blacksmith in action was on a family visit to mining theme park Sovereign Hill. I remember the huge bellows, the shocking purple-orange of the embers, and a man in an apron (the forge, along with the barbecue and the Masonic Lodge, being the only acceptable place for an Aussie bloke to wear an apron at that time) turning out miniature horseshoe after miniature horseshoe. My parents bought one for me. It was not much bigger than a matchbox. I think now of that blacksmith, his potential for breadth and expression narrowed to something akin to mass production. Miniature horseshoe after miniature horseshoe. Gawked at by tourists. It was like penning a dolphin in a backyard pool.

My nascent notion that blacksmithing evidenced supreme masculinity would have been bolstered by teenage reading of boxing history. Acclaimed champions such as Jem Mace, Ben Caunt, Eric Boon and Joe Jeanette were blacksmiths. So was sainted Maitland prodigy Les Darcy. Most notably there was Bob Fitzsimmons, “The Fighting Blacksmith’, one of the greatest boxers to ever lace a glove. He carried two stamp punches wherever he travelled, one with his name and the other with a star. He was said to seek out local blacksmith shops when away from home and work at the anvil as a unique form of ring training. The blacksmith-boxing link was also used by Dickens in Great Expectations, where Pip longed to emulate his brother-in-law Joe Gargery, a blacksmith and pugilist. This reinforced my supposition that blacksmithing was hypermasculine, primarily European, and archaic.

My great-great-great-great grandfather was a blacksmith in Silesia. His great-great-great-great grandson was born in Australia with no manual dexterity and a surfeit of uncertainties. For dress-up day in my first year of school, I costumed myself as a schoolgirl, with unhappy results. For dress-up day in my second year of school, I wore Ned Kelly’s armour made from cardboard and silver paint and felt safe and secure. Ned became the most important folk icon of my childhood, almost a talisman. I read and reread the story of Kelly and his gang stealing plough mouldboards and shaping them into armour in a bush forge in 1879, using a green log as a makeshift anvil. This was blacksmithing at the heroic level. (An alternative theory claimed that compliant local blacksmiths made the armour in their own forges, but testing in 2003 by the Australian Nuclear Science & Technology Organisation confirmed that the metal had only been heated to bush forge levels, about 700°C, rather than 1000°C-plus in a professional forge. This testing, at the Lucas Heights nuclear reactor, illustrated how minimally forged metal changes over time; the secrets of the armour’s creation were imprisoned within the object, as if holding time in suspension.)

Small wonder that I associated blacksmithing with male physical prowess, conflating it with the blunt and limited images of manhood that were preeminent in my small country town. The idea that a blacksmith could be sensitive, female or create work beyond the crudely functional was outside my sphere of understanding. Counter examples could be found then, and especially now, across Australia. I discovered two exemplars while wandering on the far side of the Pacific.

Into the USA

Looking at the United States of America is like peering at the ocean through a microscope. The United States – like everywhere, but probably more so – has labyrinthine intricacies lurking behind the façade of singularity. This we know: and yet, while visiting there, I found myself continually trying to resolve delicate nuances into cast-iron generalisations. This is the curse of a stranger in a strange-even-if-familiar land. The traveller extrapolates from instants where time intersects with geography; these apprehensions could be far different if those intersections were a year or a day or a minute later or earlier. They might feel emblematic, but they are flimsy, anecdotal, fleeting.

Blacksmithing, by contrast, produces objects that are the opposite of ephemeral: vigorously extant items that provide sharp contrast to the elusiveness of travel. Blacksmithing stops time. It takes the element Fe, with or without the presence of a small amount of C, and excites the molecules, and shifts atoms from one place to another through physical persuasion, and freezes the resultant form, and creates something unique that from that instant on will resist flood, drought or ice storm and be exactly as it is.

The first time I went to the USA I stayed in a bleak YMCA basement room and trudged through frozen slush to visit every Manhattan gallery I could find. On my second visit, a few years later, I ventured through a panoply of biomes on the west coast, entranced by natural beauty. The third time, I was the report writer on a visit by Anangu and other educators to Native American pueblos and schools between Albuquerque and Taos. I learned and relearned on each incursion that the USA is multivalent, with pockets of the very best and very worst and very middling that humanity can offer.

I returned to the USA because it is – beyond Australia – my richest cultural wellspring. It is home to much of my favourite literature, music, art, and so home to many of my dreams and wonderings. I spent most of my time on this trip in small towns located in poor, overlooked states (New Mexico, South Carolina, Georgia) interspersed with plunges into huge cities. This amplified the awareness of variance.

Yes, certain verities persist. The intertwining of racism and liberalism creates a rope that is knotted around the body politic. Religion is a big deal. The level of economic inequality is mind-addling. There is much that is unresolved in the relationship between non-Indigenous USA and Native Americans. But within each stream, a multiplicity of divergences.

During a month in New Mexico, I went to pueblos and looked at historic pottery and arrowheads and thought about the erasure of Native American culture. This resonated, coming from a country where for a very long time White Out was splashed across the pages of history. I spent my last two days in the USA in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the object that beguiled me most in that labyrinthine treasure box was a bottleneck basket woven by an unnamed Tübatulabal artist in about 1880. I lost track of time, peering through the glass of the cabinet, unable to move past a yearning to hold it in my hands. It was only later that I discovered that the exhibition of works from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection —of which this was part—was controversial. Native American advocacy group Association on American Indian Affairs issued a media statement quoting executive director Shannon O’Loughlin as saying, “Most of these items are not art: they are ceremonial or funerary objects that belong with their original communities and could only have ended up in a private collection through trafficking and looting.” It put me in mind of the ongoing anguish around the Strehlow Collection of sacred objects held under lock and key in Alice Springs. Covetousness is not confined to any one place or time, and interactions that look to be one thing at one moment can appear to be something quite different later on.

I was puzzled in Atlanta’s High Museum of Art to see words by Jonathan Williams emblazoned in huge letters on a wall of the exhibition Way Out There: The Art Of Southern Backroads: “We rootless Americans are epiphytic. We make up beauty out of the air, and out of nowhere.” The neighbouring exhibition was Hand To Hand: Southern Craft Of The 19th Century. Its masterworks included quilts, baskets, pots, a chest of drawers. Their beauty may have been ineffable but the processes by which they came into being were not remotely epiphytic.

A more compelling counterview to Williams’ airy assertion was put by Dr Peer Marzio, who told the American Craft Council 2006 National Leadership Conference, “When this country was first settled, most of the people who came were conservative Protestants. They were against what was going on in European society… they were against the visual arts. They believed that making valuable objects and embracing them was a sin… They believed that “artistic” objects, whether they were paintings or chalices or garments, were getting in the way of the individual’s relationship to God. To them, art and craft represented pride and greed…”It made me think of my upbringing in rural Australia where expressing a longing for beauty was regarded as deeply suspect behaviour – and yet the best tradespeople were acknowledged throughout the region, and the quality of their handiwork admired. Just don’t call it art, craft or beautiful.

The National Cathedral provokes reflection on religion and nationalism, but also on what lasts. It is a reasonable assumption that Nol Putnam’s gates will be there for a very long time. By contrast, in 2017 two stained glass windows commemorating Confederate generals were removed from view at the Cathedral. This was a direct response to the massacre in Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church when white supremacist Dylann Roof opened fire on praying parishioners. Objects have to live within the world. So do makers, rising to the myriad challenges of maintaining focus on a vocation despite the distractions and pervasive pessimism of contemporary life.

Smithing

How does the Folger Gate function within its environs? It stands deep inside the USA’s most prominent Christian building, but it is not an overtly religious object. It is neither sword nor plough-share. It was privately funded but has no function of exclusion. It pretends no link to Native American or African-American culture, but its maker is an avowed anti-racist who laboured for years to improve educational opportunities for marginalised students, most particularly Native Americans.

Many enslaved people were trained as blacksmiths, increasing their value as an “asset’. This is explicated by the remarkable James W. C. Pennington, the first African-American to take classes at Yale University, in his memoir The Fugitive Blacksmith. Lady Emmeline Stuart-Wortley, visiting the USA in the 1840s, wrote of “a large number of slaves, who seemed to be forging their own chains” — but this was an observation on African-American blacksmiths at Washington Navy Yard. At that time they were paid 80 cents per day while their white counterparts doing the same work were paid $1.81.

Of all the crafts, blacksmithing has the clearest link to settler culture. There was at least one blacksmith on the Mayflower. It is extremely likely there was a blacksmith or someone with those skills in the English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia from 1607, and in the Spanish settlement at St Augustine, Florida founded by a conquistador in 1565. First Nations people in different parts of what is now the USA worked with native copper, but this was very different to the primary tasks of the early blacksmiths: creating tools for subduing the land and the people living on it. There is a close link between blacksmithing and armoury, as well as farrier work, wheelwrighting, toolmaking. The word “smith” is said to come from Proto-Germanic root words meaning both “skilled worker” and “to smite”. The Folger Gate can be regarded as the great-great-great-great grandchild of funerary gates made in Silesia (and Germany, as it then was, Italy, England) in the 1700s. There are examples of gates from that time that share the same overall shape as the Folger Gate, the same cruciform central design, and even similar smithed flowers and foliage. Skilled workers have been smiting hot metal to create gates appropriately grand and appropriately sombre for prominent burial sites for several centuries. A family resemblance remains. Unlike cast iron, no two blacksmithed pieces are identical. The gates are authored works, playing with ideas of repetition within a matrix of constant variation.

Blacksmithing produces objects that endure. We drove eight hours north to visit Nol Putnam’s forge and stopped overnight at a highway motel. In the morning I hooked into the free breakfast: orange juice, tinned fruit, yoghurt, a biscuit and gravy, a bagel with cream cheese and grape jelly, coffee. At the conclusion I deposited the following into the trash can: one plastic cup, one Styrofoam cup, one Styrofoam bowl, two Styrofoam plates, one plastic yoghurt container, one plastic cream cheese container, one plastic grape jelly container, two plastic spoons, one plastic fork, one plastic knife. Multiply that by every person having a hotel or café breakfast across the United States, and multiply that again by the number of days in a year, or a lifetime. The USA is sinking under one-and-done disposable goods. This is the fifth straight year that more than 17 million new cars have been purchased across the country. How can the land where excess is smiled on as kindly as success avoid submersion in landfill? What can ironwork communicate to this and coming generations about the value of sustainable objects?

Nol

(Sounds of Nol’s smithery as background sound for reading.)

Nol Putnam met blacksmithing at its lowest (USA) ebb, and has spent most of the last half-century helping to revivify it. He is tall, sinewy, straight-backed, with a vigorous moustache and thick grey hair. We visit him at his Virginia house and sit at a long wooden table that used to belong to his mother. He has made sweet yeast buns and coffee. While talking, we watch the arrival and departure of a pair of eagles through his living room window while his noble dog Jack slumbers. A more convivial scene could not be conjured.

Even beyond his work, Nol fascinates. Born in Massachusetts in May 1934, he has deep taproots in Virginia soil, equipoised with Boston Brahmin heritage. He can trace blacksmithing to his great-great grandfather John Turner Lackey of Virginia (whose son was said to have had a forge, and whose son—Nol’s grandfather, Henry Ellis Lackey – was a naval engineer skilled in working with metal.) His parents divorced when he was young and Nol became the seventh of eight children in a blended family.

“My father came from the aristocracy of New England, people influential in education, medicine, science, politics, law,” Nol says. “One relative was President of Harvard. Another advised President Kennedy. I have cousins who helped get us into the Vietnam imbroglio.”

The past is present as Nol talks. He confides that when locals talk about “the war’”they are referring to the Civil War, not more recent conflagrations. ( “The red animal…the blood-swollen god.” – Stephen Crane.) One of Nol’s great-great uncles bivouacked about a mile from where we are sitting, en route to Gettysburg fighting for the Confederates under General Lee. He has at least ten relatives who were killed fighting for the Union, buried not so far away at Bremo Bluff. “Wars are idiotic anyway, but this one – fought over the right to enslave people, although now of course they change it and say it was about states’ rights – it really pitted families against one another.”

His abhorrence of war does not mean he devalues service. He believes his three years in the Army were formative, as well as helping him get through college via the GI Bill. The day he was discharged was the day the Cuban Missile Crisis began. (A curious side point: at least one source, Garrett Graff, claims that the lower level of the National Cathedral where the Folger Gate now stands was intentionally flooded during that October 1962 crisis to provide emergency drinking water if hostilities intensified.)

He studied history, became a teacher at Lenox School in the Berkshires, and led a successful education program for Native American students. By 1972 he was worn out, had a teetering marriage, and quit. He walked out with diminished energy, an uncertain future, a raft of ongoing close relationships with former students, and a book he souvenired called The Art of Blacksmithing by Alex Bealer.

At that time most of the major crafts had undergone a process of rediscovery in the USA. Blacksmithing, Nol says, was the last. “Blacksmithing has never been considered an “art craft’. Your hands are dirty. You are blue collar. When we started our national blacksmithing organisation in the 1970s we scrounged junkyards for old tools. Then we started making stuff that the metalsmiths looked at and the American Crafts Council looked at and they didn’t think it fitted what they wanted. In the end, finally, they decided it was a craft, not whatever else they’d deemed it to be.”

At this time Nol had minimal income, was living on a farm where he milked one cow by hand each day, and had created a little forge in a tumble-down chicken shed. “I had my dad’s stone hammer, two pairs of tongs that cost three dollars each and the wrong kind of coal. I would open up The Art of Blacksmithing, find something to make and do what I could.” For the next five years this meant making hooks, fireplace tools, hinges. “At night my shoulders would ache so badly I’d want to cry, but we weren’t starving to death. We were relatively self-sufficient, and I was stubborn. I knew I didn’t want to make armour, knives, jewellery. I wanted to do bigger architectural ironwork: gates, railings, balustrades. But to get there I had to go through a lot of years of learning to master the material, what you could and couldn’t do with it.”

Why did his aspirations transcend the conventional parameters of the blacksmiths’ shop? Nol points to where I am sitting. This was the place at his mother’s table sometimes occupied by the artist Alexander Calder when Nol was a child. “He would drink wine, fall asleep for ten minutes, call for more wine, then pull out wire and a little pair of pliers from his back pocket and make a doodad. He was a family friend along with people like Malcolm Cowley (author and editor), Van Wyck Brooks (Pulitzer Prize winner), painter Peter Blume. They would drink bad wine, eat spaghetti and talk about the war. It was this rural but cosmopolitan intellectual atmosphere, and by osmosis things were coming in.”

This sensibility found its ideal conduit, “the first day I lit a fire, grabbed a piece of scrap iron from the junk pile, heated it, put it on the anvil, hit it – and it moved. That just blew me away. That’s when I decided I would become a blacksmith. Smithing is a long and dirty road but that amazement and joy at seeing hot iron move, that hasn’t left. Iron is infinitely flexible, a beautiful material to work. You can cut it, you can chisel it, you can twist it, pound it together, draw it out, then it’s just up to your imagination what you do with it.”

Jack is roused from somnolence and we embark on what might be the best “commute” in the country. The journey from Nol’s home to his workplace is a one-minute walk over a creek, past a duck pond, through softly sighing trees to his purpose-built forge. It contains thousands of tools, most homemade. This has been his working space since 1992 and he moves through it with economy and fluidity. Nol himself has written of “the dance of the mind and a dance with the anvil’. He heats a piece of pure iron and makes some telling blows with one of his hundred-odd hammers, then continues the process with a foot-operated pneumatic hammer. He demonstrates his control over this fearsome machine by using it to close the open drawer of a matchbox without creasing the cardboard.

As he shapes the blunt metal into a delicate leaf, he reflects on moving from making small utilitarian objects to large architectural pieces to sculptural forms. “Romans invented the file. Neanderthals invented the hammer. The things we do have not changed all that much. How we see it, how we move it, what we create with it, that’s changed. There is some extraordinarily beautiful ironwork currently being done, it’s almost classic but it’s new, taking Art Nouveau forms and going off into the ether with that. It blows me away and stands against that unfortunate rush towards universality and sameness.”

The iron is pushed back into the fire and emerges glowering with 1100°C heat. Nol smooshes it against the anvil with the rounded peen of his hammer as easily as a chef shaping pastry. He incises the central vein of the leaf using a pedal hammer and handled chisel, tilting its head to move the line forward. When the leaf is finished he rubs it with a home-made elixir of beeswax, linseed oil and turpentine. The dips and curves in the metal change colour as it turns in the hand. He has long embraced the maxim of Bauhaus architect Mies van der Rohe: “God is in the details’.

This philosophy is extant in his National Cathedral gates, where every rivet and bloom is subtly varied. He is embarking on another commission for the same venue: a contemplative bench, a candle holder and three crosses. The cathedral has work by fifteen of the USA’s great blacksmiths from Samuel Yellin onwards. What does it mean to Nol to be asked to make work to sit in perpetuity beside that of his finest predecessors’? “I don’t think about it,” he says. “I really can’t. Don’t.” His voice falters. He slips for a moment under a wave of emotion. He is making work that is, in his words, “all but timeless’, but the human body is less resilient.

He knows his blacksmithing days are drawing to a close. This will probably be his final great work. “Physically, I’m tired. It is getting harder, and I’m not much interested in miniatures. I know that there is something out there I am going to do that will involve the knowledge I’ve gleaned from these past years, but I don’t know what that is yet.”

This is a tough realisation for someone who not just loves but embodies his profession. “Blacksmiths link the four elements: earth, fire, wind and water,” he says. “Iron has a great mythological history. People who could work iron were accorded a status that other folks didn’t have. On the steppes of Asia the tribes were ruled by a triumvirate of the prince, the shaman and the blacksmith, and no decisions were made without all three concurring. In West Africa a blacksmith was the only craftsperson allowed to ask the King for the hand of his daughter in marriage.

“Priests in Egypt had iron that came from the sky – meteorites. That was the first iron that was worked and was more precious than gold. There is always alchemy afoot in the fire. It’s a wonderful, rich history that comes down. It is a connection to the land. Iron oxide is what makes our blood red. Iron gives colour to the trees in the fall. It is ubiquitous.”

He is acutely aware of his place along the timeline of blacksmithing. He says that the USA way is to understand the traditions of the craft but not be bound by them. He draws comparisons with sword makers of Japan or blacksmiths in France and Germany, all places where the traditional structures of the profession endure. He sees the benefits and deficiencies of that rigidity but is grateful to have worked within the national ethos of flexibility and self-reliance.

“In this country, tradition gave way to necessity,” he says. “The capacity to make do from what you have is a good skill. Tradition is something to stand on but can be an inhibitor. I like working out my own problems. I will often go to bed with a particular problem I’m trying to solve and wake up in the morning with an answer. I rely heavily on intuition, dreams, or I go for a long walk with Jack and something will appear.”

One blacksmithing tradition he values highly is the responsibility to pass on knowledge. A very small example: many years ago Maine’s Bud Ogier showed him how to make a ladybug on the head of a rivet. Nol estimates he has since taught hundreds of people in workshops the same technique.

A tradition he is less interested in is the retention of blacksmithing as the domain of men. “Surprisingly, males are finding that women have many and varied interests,” he notes dryly. “I have a friend in Penland, Elizabeth Brim, who took feminine images (such as tutus, pillows, strappy sandals) and created them from metal in an eminently masculine environment and blew everybody’s socks off. Ellen Derkan from Iron Maiden Forge creates lingerie in iron and has runway shows. My young friend Caitlin Morris is a very thoughtful person I’ve had wonderful conversations with about male and female approaches to life and blacksmithing. She’s going hammer and tongs, to coin a phrase.”

Nol turns off the light in his shop, whistles up Jack, and we walk the 125 metres back to his house. He is weary from hours of smithing the day before. He has some designs he wants to work on, as well as the memoir he is writing. He says they are equally taxing on the brain but easier on the joints. As he lopes over the stream, loose-limbed and upright, it is hard to believe his physical powers could be waning.

Before we leave I ask him a provocative question: when mass-produced items can be purchased cheaply, why bother with something expensive and bespoke? “It is the difference between feeling in your hand a wood-handled screwdriver and a plastic-handled screwdriver,” Nol says. “It’s aesthetic. It looks better, feels better and in some way it is a call back through the years to the way we lived.”

Travelling south from Nol’s eyrie we pass Carl Sandburg’s latter life abode below Table Rock, North Carolina. Sandburg wrote that “smoke and blood is the mix of steel’.

Caitlin

(Sounds of Caitlin’s smithery as background sound for reading.)

A wending drive through cloud and forest up and over the Blue Ridge delivers us to the John C. Campbell Folk Art School in Brasstown. This is almost a second home for blacksmith Caitlin Morris. It is where she took her first class as a curious beginner a decade ago, where she spent four months in 2017 as a live-in fellow developing her smithing and tutoring skills, and where she is now a sought-after sessional teacher. When we arrive she is heating strips of mild steel with an oxy-acetylene torch and shaping them into signage brackets. There are about a dozen people working noisily in the shop. Caitlin is in the middle of the maelstrom. Her movements are precise, her demeanour calm, and she works in harmony with the two people assisting her.

This is a long way from Vermont where she spent her childhood and studied Psychology and Communication Disorders at university. She progressed to a satisfying job as Director of Operations for a small business doing Veterinary Pathology. Then she discovered blacksmithing. The story goes that she wanted a new hobby, made a list of every idea in an Excel spreadsheet, then clicked the alphabetise button. Blacksmithing zipped to the top of the list. It became an enthusiasm, then a passion, and now a vocation. “No-one in my world was doing anything like that,” she says.

Even in 2019, however, she is routinely categorised not as a blacksmith but as a female blacksmith. The day before our catch up a man took her photo and then said “You don’t look like a blacksmith’. “Just those six words,” Caitlin says – and the fact that she has counted them indicates something. “Every time I am in public blacksmithing I hear something along those lines. Statistically I am still an anomaly, but the numbers of women are increasing.”

This is borne out by her teaching career, through Ms Caitlin’s School of Blacksmithing in Frederick, Maryland. “A lot of folks specifically seek me out because they are looking for a female teacher. I don’t have the height or strength that some other people have so I teach from my own body’s understanding of what’s going on, my body mechanics. When I was taught, I had someone give me a two-by-four and tower over me and yell “Hit it! Hit it harder!” It’s interesting to see that is still predominantly how people are taught. If I see someone struggling to hit the metal hard enough to make it move, I will take them aside and say, “That approach does not work for everybody; here are the secrets and what needs to happen, because that brute force approach has never worked for me.” It reconfirms to me that I’m in the right place doing the right thing.”

“When we made things, we accumulated a certain kind of knowledge, we had an awareness and an understanding of how materials worked and how the human form has evolved to create from them.” – Alexander Langlands

A focus on becoming a better teacher has taken time away from her own making in recent years. At the same time, she is energised by being on the leading edge of a new paradigm in disseminating blacksmithing knowledge. The old apprenticeship model is barely present in modern-day USA. Instead she has learned through classes, conferences, the internet, books, and informal interactions with other blacksmiths across the country. In turn, she places a high priority on playing her part as a knowledge conduit. “The most important thing of all is to pass on information,” she says.

Caitlin is one of the founders of The Society of Inclusive Blacksmiths, an organisation “dedicated to intentionally fostering equity, diversity, and inclusion in the field of blacksmithing’”that met for the first time in Portland, Oregon in August 2018. The group’s philosophy is that, “There are demographically underrepresented groups in blacksmithing from the hobbyist to professional level, and this is detrimental to the field. The absence of the voices, creativity, and economic participation of these populations is damaging to the members of those underrepresented groups who do Blacksmith, in the form of increased likelihood of harassment or harm, and a decreased likelihood that they will continue to Blacksmith due to a variety of real and perceived barriers. This lack of diversity also limits the craft, and by fostering a broader participant base, the SIB encourages a community that expands and re-imagines what blacksmithing can be.’

“My gender has nothing to do with the actual metalwork I’m doing, but it can be a challenge in a variety of ways because folks aren’t used to considering people like me in this profession,” Caitlin says. “That shows up in everything from the height and size of tools and safety equipment to the way people interact with me. I take advantage of people’s surprise by saying, “If I can do this, you can do this.” But I am already looking past gender to the other barriers people face such as race, physical or mental challenges, and other visible and invisible things that make it harder to get into blacksmithing. I am so delighted I got an opportunity to work with a woman in a wheelchair last week. I’ve worked with folks who do not have stereoscopic vision. I dream of designing a fully accessible blacksmith shop from the ground up with spaces where I could work with people with a variety of physical limitations. With blacksmithing, you can’t touch hot metal directly so we’ve developed tools to overcome the challenge of not having fireproof hands. So much of this technology is already assistive; it just needs to go a bit further.”

She has a lot of affection for the blacksmithing community, while noting that many members have a dramatically different world view to her own. “Blacksmithing is a lens through which I can see people beyond their political beliefs,” she says. At the John C. Campbell School there is an unwritten rule that politics is not discussed. This serves to throw the focus back onto the thing that unites participants: a shared joy in the skilful transformation of hot metal.

“In blacksmithing you are generally working without a lot of colour. It’s monochromatic but you have the texture, you have the light, and you have the form. That limitation is fantastic because it really challenges you to pay attention to the different ways the object can be seen. I love to engage with things at the “How-the-heck-did-they-do-that?” level. There is great satisfaction in working through challenges. And there is the incredible, almost gut-level reaction to the beauty of the metal itself.

“The moment when I fell in love with blacksmithing, my teacher was making a leaf and the metal was glowing these most beautiful sunset colours. That rosy orange-red colour in a dark room is just spectacular. The way that the metal moves, the way I can see myself getting better every time I am at the forge – or every other time, anyway – all that is part of what I get out of it,” she says.

There is also the pleasure of meeting someone like Nol Putnam. “I took a tour of the National Cathedral and saw amazing blacksmithing work, and the Folger Gate is gorgeous. It was so exciting to see that masterwork then be able to go to the source and ask Nol lots of questions. The requirements of air flow and privacy, the different density of leaves in different parts of the gate, it is brilliantly done. To be honest, most of the conversations that Nol and I have are not about the technical aspects of blacksmithing, which is what I talk about with most smiths. The conversations with Nol are focussed on art and beauty. His thoughts and meditations on beauty, line and form are so special to me.”

Hinges, hooks, embers

Time is remorseless. Nol’s blacksmithing days are drawing to a close. One day Caitlin will hang up her apron and hammer for the last time. What happens to all the knowledge encoded in their muscles and bones? What is a maker who cannot make any more? Where does the making go? Does it terminate somewhere between the mind (or the heart) and the hand, like an electrical short? Does it remain entombed within the body of the maker-who-cannot-make, or does it go somewhere else? Is it imprinted within the material that is no longer shaped – an idea, a potential, sleeping within the unshaped form? Beethoven’s deafness did not stop him from composing. Nor did Milton’s blindness stem his poetry. But a maker’s work is only realised through the doing. The vision, the thinking, the potential is as ephemeral as steam if the work remains unmade. More reason to create while time allows.

There is a pretty epigram that most Google hits attribute to Bob Dylan: “The purpose of art is to stop time.” (If it seems too direct for the elliptical Dylan, that’s because it probably is. Certainly he said to Allen Ginsberg in a 1977 interview, “You can make something lasting. You wanna stop time, that’s what you wanna do.” This idea is hardly new, dating at the very least to Schopenhauer from the century prior who wrote that art “plucks the object of its contemplation out of the stream of the world’s course, and has it isolated before it… It therefore pauses at this particular thing; the course of time stops…” Whether stopping time is – in all or part – the purpose of art and making is at least arguable, but it is one by-product or function.

John Rawlings, a ceramicist and painter from Montana, gave me a different perspective on the art-stopping-time idea. “What they have discovered therapeutically is that when people are making things the clock that is in their brain stops ticking,” he said. “The horror of dragging time in hospitals disappears because if people are engaged in that creative process producing work, all of a sudden time goes. I believe that making art is prayer. It depends what god you’re praying to. The best parallel I have is a prayer wheel. You come, you spin it, and something happens.”

How did blacksmithing help me make sense of the United States? I envision the USA as a cephalophore – a saint carrying his/her own head. So much in this sprawling polyglot is wonderful but it labours under the leaden weight of carrying the bizarre Trump and his acolytes. While the signifying-nothing sound and fury rages, there are people doing work that is true, making things that will outlast the current political pitifulness, outlast every person alive today, outlast even the Styrofoam in the hotel trash can. (Well, perhaps not that.)

People are making and teaching and sharing. This is a valid and valuable response to the Age of Despair, to create that which is sustainable and beautiful. We can hope that blacksmithing, no longer monogendered, will open further to people across the economic spectrum, to people of different racial backgrounds and with different physical capacities. And perhaps some of these future smiths will create work as marvellous and as enduring as the Folger Gate, and pass on their own knowledge with the open-heartedness and skill of Nol and Caitlin. These, crucially, are some of the things that last.

Further Reading

Bealer, Alex The Art of Blacksmithing, Harper & Row, 1969

Einstein, Albert via Saturday Evening Post interview 26 October 1929

Ginsberg, Allen interviews Dylan, Bob 28 October 1977

Graff, Garrett M. Raven Rock: The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself While the Rest of Us Die, Simon & Schuster, 2018

Langlands, Alexander Craeft: An Inquiry into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts WW Norton & Company, 2017

Marzio, Dr Peter, in “Shaping the Future of Craft’, American Craft Council 2006 National Leadership Conference, Houston, Report. ACC, 2007

Ms Caitlin’s School of Blacksmithing

“Native American group denounces Met’s exhibition of indigenous objects’, The Art Newspaper:

National Cathedral, Washington DC:

Pennington, James W. C. The Fugitive Blacksmith; or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States, Charles Gilpin, 1849

Putnam, Nol & Berger J. Lines in Space Blue Moon Press 2010

Sandburg, Carl “Smoke and Steel” in The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg, Harcourt, 1970

Schopenhauer, Arthur The World as Will and Idea Vol. 1 Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. 1909

Society of Inclusive Blacksmiths

Author

Michael Winkler is a writer who lives in Melbourne/Naarm, Australia. He is currently researching hidden grief, and completing a project on pain artiste Joe Grim’s visit to Australia in 1908-09. You can find our more here: www.michaelwinkler.com.au

Michael Winkler is a writer who lives in Melbourne/Naarm, Australia. He is currently researching hidden grief, and completing a project on pain artiste Joe Grim’s visit to Australia in 1908-09. You can find our more here: www.michaelwinkler.com.au