Geng Xue, Mr Sea, 2013–14, stop-motion animation of porcelain sculptures; tableau/installation of same sculptures, video: 13 min 15 sec, installation: dimensions Variable, Image courtesy White Rabbit Collection Sydney

Welcome message:

Porcelain Encounters and Clouds of Silica

Before I travelled to Jingdezhen in the winter of 2016, my knowledge of its thousand-year history and continuing significance in the global porcelain trade was as almost as sketchy as that of the Europeans who first saw imported Chinese porcelain almost 500 years ago. They speculated wildly about what this fine, white material could be made of, with guesses ranging from “a kind of juice” that coalesces underground (Cardon in 1550), to Scaliger’s fanciful 1557 hypothesis that it was made from eggshells and the shells of umbilical fish, pounded into dust, mixed with water, shaped into vases and buried underground for a hundred years. Marco Polo’s explanation was slightly more realistic:

The dishes are made of a crumbly earth or clay which is dug as though from a mine and stacked in huge mounds and then left for thirty or forty years exposed to wind, rain, and sun […] By this time the earth is so refined that dishes made of it are of an azure tint with a very brilliant sheen.

Had you asked me then about the nature and history of porcelain my response would have been as vague. But in 2015, quite by chance, I encountered Geng Xue’s 2013–14 Mr Sea (海公子), in a Shanghai gallery. The protagonists of her video are jointed puppets made of blue and white glazed porcelain, brought to disturbing life with stop motion animation. Their undulating, trance-like movements through an eerie porcelain landscape of coral-like branches and creepy shadows depict the erotic encounter between a scholar and a beautiful woman—a liaison that ends very badly indeed. Mr Sea was beautifully, seductively nightmarish, and the artist’s technical virtuosity was immediately evident. The work includes an installation of porcelain figurines and backdrops (shown together with the video in Ritual Spirit at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery in 2017) that emphasises both the fragility and the narrative possibilities of the material. I became fascinated by the work of Chinese artists who, like Geng Xue, draw on their history and craft traditions to make work that seamlessly enters the global contemporary.

Mr Sea adapts a story from a famous Qing Dynasty collection of supernatural tales. Pu Songling’s Liaozhai Zhiyi (usually translated as “Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio”) is an extraordinary seventeenth-century collection of 500 fables featuring assorted shape shifters, ghosts, goblins, fox spirits, scholars and demons among its cast of characters. Composed over a roughly 30-year period, many of the stories focus on ill-fated romances between mortals and supernatural beings. This juxtaposition of sexual desire and the uncanny especially interested Geng Xue, as we shall see.

I was already familiar with the work of Liu Jianhua and other contemporary Chinese artists working in the medium of porcelain, but I knew of Jingdezhen only as the place where Ai Weiwei’s famous sunflower seeds were fabricated and painted. Certainly, it had never occurred to me to go there. But life is sometimes almost as randomly strange as Pu Songling’s supernatural stories. In December of 2016, after the White Rabbit Collection had partnered with the UK-based Centre for Chinese Visual Art, the opportunity to visit Jingdezhen most surprisingly presented itself. Professor Jiang Jiehong had initiated a research project investigating the viability of traditional Chinese craft practices and their connection with the work of contemporary artists. Everyday Legend: Reinventing Tradition in Chinese Contemporary Art, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, aimed to examine the decline of traditional crafts in a rapidly urbanising and globalising China, exploring possibilities for their revitalisation by contemporary practitioners. The premise of the research lay in China’s twenty-first century socio-cultural context: can contemporary artists re-examine, re-imagine and engage deeply with tradition yet still be critically reflective? This question dovetailed beautifully with my research interest in relationships between ancient and contemporary Chinese art practices, and the fluxing local/global nature of contemporary art.

So, representing the White Rabbit Collection I joined the first Everyday Legend field trip, studying textile production in Suzhou and porcelain in Jingdezhen. I flew to Shanghai and met Professor Jiang and other project partners, Professor Oliver Moore from the University of Groningen, Professor Lv Shengzhong from China Central Academy of Fine Arts, Nan Nan and Sebastian Liang from Beijing’s New Century Art Foundation and facilitator Hiu Man Chan and embarked on a short but profoundly significant journey. This essay reflects on the significance of Jingdezhen to both Chinese and foreign ceramic artists and explores tensions between local and global, past and present, and between artisans and artists. It raises more questions than it answers, as did the research project itself—it is intended to contribute to an ongoing conversation.

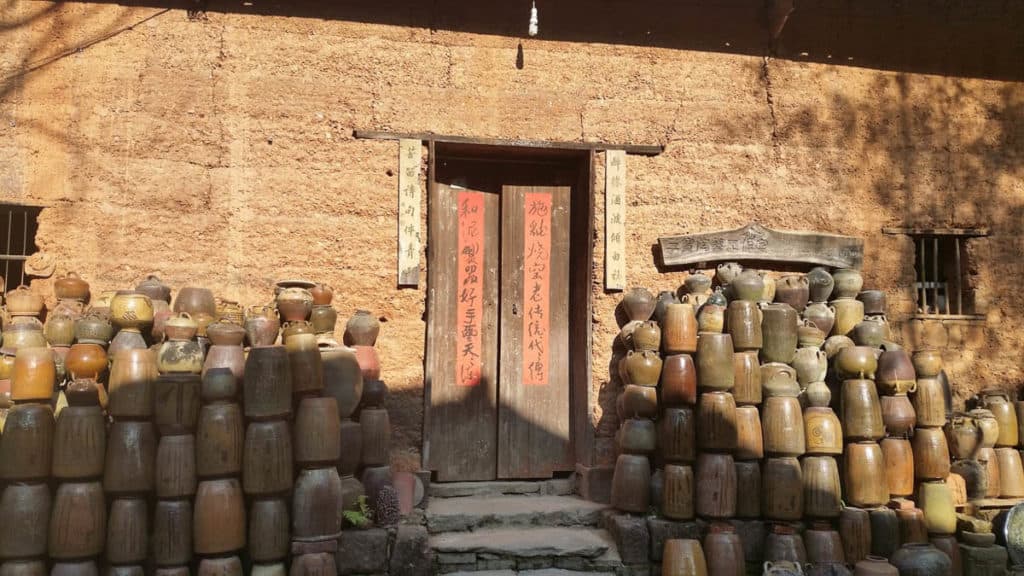

A term used by local artisans of Jingdezhen pottery workshops and kilns—the insiders—describes the outsiders, the throngs of visiting artists, curators, researchers and writers: they are jingpiao, or “Jingdezhen drifters’. The expression derives from an earlier idiom. Beipiao, meaning “northern drifters’, was common parlance in the 1990s and described young artists, musicians and other creatives who drifted into Beijing to make a precarious living there. Today, the term jingpiao describes all the waidiren or outsiders—Chinese or foreign—who find themselves in Jingdezhen. Why does this small, prefecture-level city in one of China’s poorest provinces draw so many people from across the globe? To find out more, I’ve spoken with four artists who make work there, or whose work is in some way inspired by their time there. Liu Jianhua and Geng Xue, whose work is held in the White Rabbit Collection, are discussed in detail, while the Australians Merran Esson and Juz Kitson provide a different point of view. I asked each artist to tell me why Jingdezhen exerts such a gravitational pull on Chinese artists immersed in their own thousand-year-long porcelain history and on foreign visitors.

Common threads emerged in these conversations. The first, and perhaps most significant, was about materiality. It concerned the “stuff” of working with clay, kilns and glazes, the physical labour of working with such materials, and the meaning/s that this embeds into their work. Another was the impact of landscape and the importance of place. In contrast to other art forms that, in this digital age, could be fabricated anywhere at all, it is the specific environment of Jingdezhen that partly explains its allure. This is a place with a long history and an extraordinarily strong physicality, as I discovered myself when I collected ancient shards beside an aggressive flock of geese on a country hillside, watched painters decorating figures of Guanyin and artisans unloading kilns stacked with blue and white vases, or wandered through the “ghost” market asking questions. “Zhende ma?” (is it real?); “Bu zhende!” (not real!) answered the vendors with disarming honesty.

Geng Xue, who lives and works mostly in Beijing, stressed the physicality of working with clay, and the sense of place that she found in Jingdezhen:

Jingdezhen is a very small place surrounded by mountains and hills, and when I set up my studio there I worked as if I was living in nature […] I would work with my friends to make clay, make things from clay, and I would work among the mountains. Sometimes we would fire the kiln to make porcelain and stay up very late […] my work contains my own labour and it’s a totally different experience from working in the studio where you are imagining everything. I think in the real environment, in nature, the working state is very different … I can monitor the dryness and wetness of the clay very carefully and I know how to make them, in what kind of shape, and I’m very sensitive about it […] I can feel it with my hands.

That final phrase, “I can feel it with my hands’, appears simple and yet is so complex. Any artist or maker of objects knows exactly what she means. Musing on the same question, Merran Esson quotes Eduardo Paolozzi on how it takes a thousand tiny hand movements to create a work of art. She wrote: “These words have inspired me for over three decades, capturing the spontaneity that happens when I work directly with clay. The word ‘touch’ is integral to what we do.” Knowledge and understanding are experienced as unified elements of the making process; thought and action are not separate. For some Chinese artists this reflects Daoist beliefs in the harmonious balance of yin and yang.

Juz Kitson has also been influenced by the landscape around the city, and by her wanderings through the chaotic streets of Jingdezhen:

Often, I’m directly influenced by my immediate surroundings and the natural landscape and mountainous ranges. For example, Yellow Mountain and areas around Gaoling have found their way into my drawings. I’m constantly visiting the street produce and meat markets and antique stalls to see what will find its way into the works, often making moulds of obscure vegetables or visiting traditional Chinese herbalists/medicine doctors.

Merran Esson’s response is more equivocal, although she realises in retrospect that her experiences at the Jingdezhen Pottery Workshop in 2008 may have influenced her more than she realised. She remembers that for the first several days it was overcast and grey: “I didn’t realise I was living in a cloud of silica.” But on the third or fourth evening there was a big wind. When she woke, she suddenly understood that Jingdezhen is surrounded by mountains. Having always made works referencing specific landsapes, whether Scottish hillsides, the Snowy Mountains in NSW or, more recently, the trees of the Monaro, Esson wondered whether she could, or should, incorporate the shapes of this Chinese landscape into her work. She was struck, too, by the enormity of Jingdezhen, the scale of production, the sheer number of kilns, factories, workshops:

I found China almost too much, it was too overwhelming […] China excited me, and it frightened me, to be perfectly honest. The influence it had on me was that it made me realise I am but a small cog in the wheel of international ceramics. If you go to China and you have the whole wheels of Jingdezhen, which I call the kilns of the world […] there’s so much going on there […] if you have that at your fingertips then you can put out a body of work that can support the international market …

… The big pot factory really opened my eyes to the size of the kilns and the potential of what anybody can do in China. It excited and scared me – partly because I realised that there were people there who could help me, but it would take me away from the handmade […] the enormity of the mass production and wondering whether we would all be sending our work to Jingdezhen one day…

Juz Kitson’s first response to Jingdezhen was not dissimilar, but she has returned many times, enthralled by what she found:

What surprised me the most was the infrastructure, the enormous industrial spaces and run-down buildings, piles of porcelain shards and silica dust covering the streets, a city bustling with artisans working around the clock […] The work ethic amongst the town has certainly had a profound effect on my practice, I relish long studio days, working day and night to create intensely meticulous handcrafted installations.

The reason I keep going back, like so many other foreign artists, is the accessibility to materials, glaze technology and firing techniques used in Jingdezhen that are inaccessible to me in Australia. The quality of the material is the highest I’ve experienced world-wide. There is a frantic energy to the city, a constant buzz of production, everyone meeting daily deadlines. A universal thread that brings the Jingdezhen locals, Chinese Nationals and International “drifters” together is our common obsession with the material.

Chinese Porcelain: A Global Brand

When I arrived in Jingdezhen in December 2016 with the Everyday Legend research team, we were guided by celebrated contemporary artist Liu Jianhua, who had been apprenticed there in his uncle’s workshop as a boy. This gave the group an entrée into workshops, artist residencies, factories and conversations with locals that would not otherwise have been possible. We examined dragon kilns snaking up hillsides, visited the newly opened Taoxichuan Art Museum and Art Precinct, San Bao Ceramic Art Village and its workshops and artist residencies. We watched kilns being packed, fired and unpacked, and porcelain ranging from kitsch ornaments to contemporary artworks in production.

No visitor to Jingdezhen can fail to be awed by its long history. Commercial pottery production is generally agreed to have developed during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE). Wares from Jingdezhen soon caught the eye of the imperial court and the emperor decreed that all imperial porcelain was to come from its kilns. The town was renamed the township (zheri) of the Jingde emperor. This was industrial-scale production long before the Industrial Revolution changed the face of Europe. Porcelain from Jingdezhen was exported to the Middle East, Korea, Japan, South and Southeast Asia and it may well be the world’s first global brand, continuing unabated for more than a thousand years. Even during the dark years of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), the factories pragmatically churned out statues of Mao instead of Guanyin figurines. Jingdezhen’s prosperity waned during the Reform and Opening Up period in the 1990s, but its decline has been arrested in recent years by the arrival of contemporary artists from inside and outside China and new studios, workshops and artist residencies, as well as by the growing international reputation of Chinese artists creating work with the assistance of Jingdezhen’s artisans and expert porcelain painters. One such artist, with generational ties to the porcelain centre, is Liu Jianhua.

An Everyday Legend: Liu Jianhua

Liu Jianhua, Autumn Leaves, 5000 porcelain leaves, dimensions variable, installation view and detail, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection

Liu Jianhua, Autumn Leaves, 5000porcelain leaves, dimensions variable,installation view and detail, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection

At the age of twelve, Liu (b.1962) was sent to Jingdezhen to work with his uncle, Liu Yuanchuang, a well-known artisan and artist. By the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed in the Jingdezhen Pottery and Porcelain Sculpture Factory, where he spent eight years learning the demanding techniques required to produce the finest porcelain By 1985, though, frustrated by a production line approach to porcelain that appeared to allow little room for creativity, Liu was one of only two students from Jiangxi Province selected to train in Fine Arts at the Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute, where he majored in sculpture. There he discovered western modernism, and the innovations of the “85 New Wave” movement that was reinvigorating Chinese contemporary art.

After graduation in 1989, Liu was sent to Kunming to teach sculpture, where he became friends with the avant-garde artists of the Southwest Art Group, including Zhang Xiaogang, Ye Yongqing, Mao Quhui and Tang Zhigang. Thinking back on this time, he said:

I can tell you that I was quite tired of porcelain when I left the factory, because I had been dealing with that material for such a long time […] if I just stayed in the factory I could see what my life would be until I retired, just like the older craftsmen that were working day by day on the same thing […] So, after I got accepted by the university I just thought that I would never touch this material again. I’d even given away all the tools to other people.

Later, in the early 1990s, it occurred to Liu that perhaps porcelain—this material that he knew so well—could after all be a solution to the questions of materiality he was exploring. He describes this revelation as like a search for the right idiom: “I decided it could be my own language.’

Liu Jianhua is particularly well-known for an ongoing series of 容器 or Vessels. Displayed in groups as installations, these celadon-glazed, non-functional objects reveal Liu’s deep immersion in porcelain history. He recreates traditional ritual vessel forms such as stem cups and wine vessels. Other shapes allude to modern, mass-produced objects. The glaze recalls Song Dynasty porcelain from the Longquan kilns, which Liu believes was “the peak of Chinese culture or spirit”.

Liu Jianhua, Vessels, 2009, porcelain, 3 pieces: 23.7 cm diameter x 10.7 cm, 27 cm diameter x 7.6 cm, 28.2 cm diameter x 12 cm, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection Sydney

The three vessels in the White Rabbit Collection appear at first to be filled to the brim with red liquid. On closer inspection, however, we see that they are not bowls at all; the top of each vessel is flat, glazed with red lang yao hong (sang de boeuf), a blood-red copper glaze first developed in Jingdezhen during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Some have interpreted this as a reference to the bloodshed and destruction of the Cultural Revolution during the “Smash the Four Olds” campaign. In a conversation at Beijing Commune gallery, however, Liu told curator Demetrio Paparoni that he was thinking about the vanishing of entire dynasties:

I wanted to make a reference to my culture and my past, that run through my veins. I wanted to highlight the fact that during the Sung [sic] dynasty plenty of extraordinary pottery objects were created […] today this culture doesn’t exist anymore.

In Jingdezhen this sense of loss and memory is omnipresent: fragments of vessels discarded and smashed long ago lie everywhere in the surrounding countryside. The vanishing of societies erased by forces of dynastic change is a conceptual thread that runs through Liu’s practice: the fragility of fine porcelain echoes the fragility of culture.

Porcelain Poetics: Geng Xue

Geng Xue, Mr Sea, 2013–14, stop-motion animation of porcelain sculptures; tableau/installation of same sculptures, video: 13 min 15 sec, installation: dimensions Variable, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection Sydney

Geng Xue (b.1983) is from a younger generation, but she is as immersed in porcelain history as Liu Jianhua. Her chosen medium reflects her deep interest in traditions of Chinese culture, inflected by her study of film and animation techniques in Germany. Geng’s subjects generally emerge from Chinese classical literature or Buddhist texts: “All the stories are the artery of Chinese history,” she says. She has made a study of ancient ceramics and paintings in museums and archaeological sites including Dunhuang, Xi’an, Luoyang, Jingdezhen and the Longquan celadon kilns. Like Liu Jianhua, she most admires “sexy” Song Dynasty porcelains:

I use them as examples or models to guide my study and even replicate; they appear very clear, very transparent and very beautiful […] such beautiful, simple shapes and with very beautiful sexy glazes. And I think I have learned a lot from ancient Chinese culture and tradition […] Without the thousands of years of history of porcelain in China, without this foundation, I think my work cannot be empowered.

For Mr Sea, however, she turned to the blue and white cobalt glaze introduced to China via the Silk Road from Persia. Blue and white porcelain is so inextricably associated with Chinese cultural traditions in the popular imagination that it has come to symbolise Chineseness. Jingdezhen is filled with blue and white wares, real and fake, right down to the streetlights along the main roads of the city.

Geng animated multiple hand-made figures and objects to reinterpret the story of a young scholar who sails to the shores of a mysterious island where he falls under the spell of a beautiful girl. It was the tragedy of erotic obsession in Pu Songling’s tale that particularly interested Geng Xue, with its positioning of female protagonists as sirens or femmes fatales. The violent arrival of a terrifying serpent with a slithering, segmented body, and the alarming hint that the beautiful girl and serpent are actually one and the same, brings their ill-fated affair to a bloody conclusion.

Geng Xue built, glazed and fired every element of the sets and characters, experimenting with lighting and camera angles to make an ancient allegory of doomed love relevant to the modern world: “I think that what you desire and what you fear are just the same, and the things you desire can even destroy you,” she says. The technical virtuosity with which both Geng Xue and Liu Jianhua employ construction, firing and glazing techniques ensures that porcelain can convey complex contemporary ideas. I wondered whether the experiences of Australian craftspeople in Jingdezhen might provide a different prism through which to examine the significance of the medium, and the continuity of the ancient porcelain capital as a centre of knowledge and transcultural exchange.

Introduced species: Australians in Jingdezhen

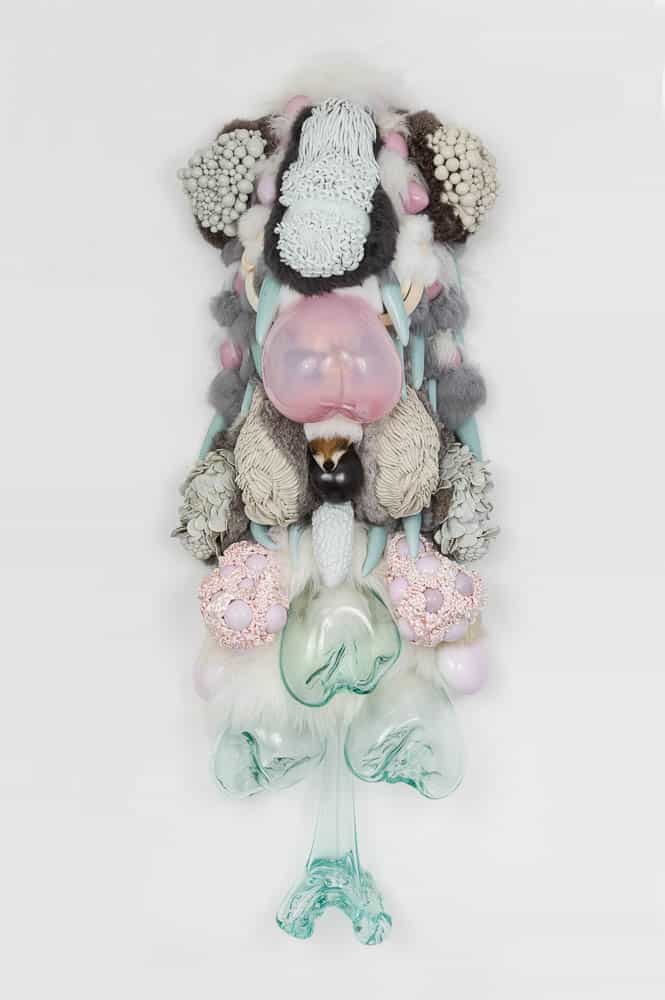

Juz Kitson, Native; That which is the subtle essence, 2017, Jingdezhen porcelain, merino wool, marine ply and treated pine, 80 x 46 x 20cm, image courtesy the artist

Juz Kitson first travelled to Jingdezhen in 2012, courageously arriving “cold” without a pre-arranged studio. She immersed herself in the sculpture factories and experimented with new porcelain clay bodies, firing techniques and mould making, working towards a major installation for Primavera 2013 at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. After six weeks, like so many others before her, she was hooked:

I was fascinated by the potential limitlessness of the city, the “everything is possible” mentality and the buzz [that] the city radiates. It was inevitable I would decide to set up a permanent studio in the sculpture factory and I have been splitting my time between Jingdezhen and rural NSW for the last six years.

Kitson’s response was not unrelated to the aims of the Everyday Legend research project. She was interested in how a place with more than a thousand years of porcelain history continues to thrive, and she was keen to learn traditions that she could recontextualise in her own work. And, she added, “I’ve always been fascinated by the age-old divide between craft and fine art.”

Kitson created what she describes as a “second home” in the Taoxichuan Sculpture Factory, where her studio sits above a huge 28 burner public gas kiln that is fired every second day. Jingdezhen for her is about materiality and access:

… the access to a vast array of greenware factories, blue and white painters, traditional glazes, for example, copper red which can take a lifetime to develop, and access to it in Jingdezhen is simply walking into one of the many glaze shops and purchasing it by the litre …

Jingdezhen has significantly influenced the scale and ambition of her work:

Given access to the large-scale kilns and glazes, I’ve been able to focus directly on conceiving work and developing techniques and new ways of making through constant experimentation and realising works in a short period of time, able to decide if a work is worth the pursuit or continuing, for my practice that is hugely significant. It’s also the time to focus I find so enriching, there are less distractions as I become fully engrossed in studio time.

Juz Kitson, Life and everything in-between, 2017, Southern Ice porcelain, Jingdezhen porcelain, blown glass, part fox pelt, merino wool wild goat hide, rabbit fur, boar tusks, marine ply and treated pine, 126 x 46 x 27cm. Image courtesy the artist

Juz Kitson’s work also reflects on exotic and introduced species, perhaps in part inspired by her complicated experience as a long-term outsider/insider in Jingdezhen. Kitson’s work, Native; That which is the subtle essence, reflects her experiences in and of China and was made in response to witnessing a Chinese lion dance. She is particularly interested in ceremony and ritual and her work often incorporates shamanistic or talismanic elements such as bones and hair. She sourced the porcelain body (called Pig’s Fat Porcelain in English) from Fujian Province. The work references exotic fruits and flowers, carnivorous plants and invasive introduced species. She says, “They are introduced, alien, exotic, indigenous and non-indigenous, native and non-native species living outside their native distributional range […] invasive species that can cause damage.”

For Kitson, works such as these represent the fragility of an ever-changing world, but they also reflect her sense of herself as a jingpiao drifter, a waidiren or outside person in a Chinese city. Jingdezhen has always been a site of cultural exchange and transnational encounters, a place of many tongues and one language—porcelain. Notions of the exotic, the alien and the “introduced species” have been associated with the porcelain trade since the first shipments from China arrived in Europe, feeding an insatiable demand that has never ceased.

Merran Esson, Potshot, 2009, slab constructed stoneware clay with copper glaze, 64x44x43cms. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Greg Piper

Merran Esson’s viridian green glazed work, Potshot, was created in 2009, the year after her visit to Jingdezhen. It’s stoneware, not porcelain, but reveals an artist musing on her responses to her time in the city, which had come about after several earlier visits to China. Esson resists overt references to Chinese influences in her work, fearful of falling into a form of Chinoiserie, and wary of Western artists “hoovering up” Chinese knowledge and expertise in a form of colonialist plunder. Yet in Potshot, memories of Chinese bronzes and Tang Dynasty vessels in the museums in Xi’an are evident. Esson commented wryly that she had perhaps originally been unaware of the influence, but having once seen those bronzes, she could not “unsee” them. Her vivid green glazes, at first suggesting oxidisation on ancient vessels or recalling the colour of jade, are present once again in her recent award-winning series inspired by the trees of the Monaro.

So where does this leave us with the big questions? Is Jingdezhen a place where art meets craft, past meets present and local meets global? Following the first Everyday Legend field trip in 2016, a workshop/seminar was held at Shanghai’s Minsheng Art Museum, where the participants were joined by contemporary artists Jin Feng, Yang Zhenzhong and Zhou Xiaohu to discuss the issues. How resilient are Chinese traditional practices? How can artists engage with them in ways that are respectful of the skills of the often poorly paid artisans and workers in Jingdezhen? How can traditional crafts be living things that avoid a self-conscious self-orientalisation? And, given the conceptual nature of much contemporary art, what is the role of the materiality of practice, the physical act of making? It seemed there were more questions than answers.

Everyday Legend is not the only research project to engage with these questions. The Central Academy of Fine Arts and Jingdezhen Municipal People’s Government staged an exhibition in Jingdezhen’s Taoxichuan Art Museum in 2017: Echo of Civilization: To Ingenuity examined the creative transformation and innovative development of traditional artistry including jade carvings and ceramic sculptures—and the Chinese zither. For the 2017 Venice Biennale, the China Pavilion, curated by Qiu Zhijie, represented the notion of buxi or “continuum”, with the work of two contemporary artists and two craftspeople who worked publicly, turning the exhibition space into a kind of workshop. Chinese art historian Wu Hung describes such approaches as a “conversation with history” in which artists and artisans “translate, transform, appropriate and refigure” traditional crafts.

Merran Esson, Red Porcelain Bowl, 2015. 15 x 13 x 16cms. Wheel thrown and constructed Southern Ice porcelain with copper red glaze. Image courtesy the artist. Photo by Greg Piper.

Merran Esson’s red porcelain bowl, thrown using Southern Ice porcelain in 2015, suggests that memories of China have been incorporated seamlessly into her ongoing preoccupation with the Australian landscape. Using an Australian porcelain body and a copper red reminiscent of Jingdezhen red glaze, she reinvents the ancient form of the vessel, just as Liu Jianhua has done. Esson told me that the first time she saw Liu’s celadon vessels she was so moved that she was reduced to tears. She has long been a fierce defender of the hands-on work of the artisan and recognised in Liu’s vessels the many years of practice and physical labour that produced such virtuosity. The tension between the hand-made ethos and the industrial-scale fabrication processes of Jingdezhen was foremost in her mind as we spoke. Esson raised a concern that caused her some unease in China, one that was also discussed within the Everyday Legend team. The relationship between visiting artists in Jingdezhen (whether Chinese or foreign) and the local, mostly anonymous, craftspeople who make or paint their work remains an unequal one: it privileges certain kinds of knowing over other kinds. In Jingdezhen this question preoccupied me, too, as I stood in front of an installation of black and white photographs memorialising hundreds of workers in one of many now obsolete kiln sites. Outsiders and insiders in Jingdezhen engage in complex negotiations between cultures, each shaping and changing the discourse in unexpected ways, but the “conversation with history” in Jingdezhen continues across divides of generation, nationality, gender and class with a common language: porcelain.

Note: the quotes from the artists are taken directly from transcripts of the interviews with Liu Jianhua, Geng Xue and Merran Esson, and from emails between the author and Juz Kitson, lightly edited for sense. The work of Liu Jianhua and Geng Xue is held in the White Rabbit Collection, where the author is the Manager of Research.

References

Elliott, Gordon, 2006. Aspects of Ceramic History, Vol 2, GWE Publications p.45

Esson, Merran., 2019, An Interview with Merran Esson, Sydney

Esson, Merran., 2016, The Stuff of Life, The Australian Journal of Ceramics [accessed 5 May 2019]

Geng, Xue., 2018. An interview with Geng Xue, Beijing

Gillette, M., 2010. Copying, Counterfeiting, and Capitalism in Contemporary China: Jingdezhen’s Porcelain. Modern China, 36(4), pp. 367-403.

Gladston, P., 2012. Problematizing the New Cultural Separatism: Critical Reflections on Contemporaneity and the Theorizing of Contemporary Chinese Art. Modern China Studies, 19(1), pp.

195-270.

Gladston, P., 2014. Contemporary Chinese Art, A Critical History. London ed. London: Reaktion Books.

Gladston, P., 2014. Somewhere (and Nowhere) between Modernity and Tradition: Towards a Critique of International and Indigenous Perspectives on the Significance of Contemporary Chinese Art Tate Papers, no.21, Spring 2014, London: Tate.

Huang, E. C., 2012. From the Imperial Court to the International Art Market: Jingdezhen Porcelain. Journal of World History, 23(1), pp. 115-145.

Kerr, Rose and Wood, Nigel, 2004. Science and CIvilisation in China. Vol 5 Part 12: Ceramic

Kitson, Juz., 2019 An Interview with Juz Kitson (email)

Leidy, D. P., 2015. How to Read Chinese Ceramics. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Leverhulme Trust and Birmingham City University Centre for Chinese Visual Arts, 2018. Everyday

Legend, Birmingham: Birmingham City University Centre for Chinese Visual Arts.

Liu, Jianhua., 2018. An Interview with Liu Jianhua, Shanghai

Liu, J., Undated. More Spiritual Than Realistic: Demetrio Paparoni interviews Liu Jianhua [Interview] Undated.

Lucie-Smith, E., 2008. Foreword: Liu Jianhua. In: D. Dan, ed. Regular – Fragile: Liu Jianhua. Beijing: Arario, p. 5.

Miller, M. a. T. Z., 2014. Scissors, Paper, Poetry: the interaction between Chinese folk art and contemporary practice. Journal of Illustration, 1(1), pp. 101-121.

Pierson, S., 2009. Chinese Ceramics. London: V&A Publishing.

Tan, E., 2008. Transformation of the Everyday. In: D. Dan, ed. Regular – Fragile: Liu Jianhua. New York: Arario, pp. 36-39.

Wu, H., 2012. Negotiating with Tradition in Contemporary Chinese Art: Three Strategies. [Online] [Accessed 28 January 2019].

Author

Luise Guest researches and writes about contemporary Chinese art. Her writing has been published in a range of online and print journals including The Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, Art Monthly Australasia, The Art Life, Daily Serving, Randian and Artist Profile and her book, Half the Sky: Conversations with Women Artists in China was published by Piper Press in 2016. She travels to China regularly to interview artists for the White Rabbit Collection, where she is the Manager of Research. Luise is currently undertaking PhD research at UNSWAD, examining the work of female artists who subvert conventions of ink painting and calligraphy. She is also a very bad student of Chinese, although she dreams of being fluent one of these days.

Luise Guest researches and writes about contemporary Chinese art. Her writing has been published in a range of online and print journals including The Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, Art Monthly Australasia, The Art Life, Daily Serving, Randian and Artist Profile and her book, Half the Sky: Conversations with Women Artists in China was published by Piper Press in 2016. She travels to China regularly to interview artists for the White Rabbit Collection, where she is the Manager of Research. Luise is currently undertaking PhD research at UNSWAD, examining the work of female artists who subvert conventions of ink painting and calligraphy. She is also a very bad student of Chinese, although she dreams of being fluent one of these days.

Comments

Dear Luise,

I am really interested in your paper. Could you share it with me. I am a PhD researcher in Lancaster, UK who is also currently studying crafts and craft community in Jingdezhen. Hope we can have some chat. I am orignially from China near Jingdezhen. You can fellow me on Twitter: @XiaofangZhan.

Best wishes,

Xiaofang