Liliana Morais follows a Japanese ceramicist who built a kiln in order to make a life between Japan and Brazil.

(A message to the reader in English.)

(A message to the reader in Portuguese.)

Kôgei is the Japanese word for craft, which in Portuguese can be translated as artesanato. Looking at the etymology and meanings of each word alone can give us valuable insights into how each society has looked at, understood, and valued the objects or skills included in these categories (as well as the people who have made/ mastered them).

The word craft has roots in Old English. Its first appearance can be traced back a thousand years ago. Throughout most of its history, it was used as a synonym of “knowledge”, “power”, and “skill”. From the nineteenth century, its meaning shifted to refer to a category of things rather than a way of doing things (being it war, a pot, or horse-riding), as it had been before.

The word kôgei 工藝 is recorded in the Old Book of Tang, from the Chinese dynasty’s name, but its widespread use in Japan only goes back to 1873 when it was chosen as a translation of craft for works to be shown at the Vienna International Exhibition. The ideogram 工 embodies the meaning of “skill” or “high level of technique”. In Modern Japanese Art and the Meiji State: The Politics of Beauty (2011), Japanese art historian Doshin Sato explains that, while gigei 技藝(or “technical art”) might have been the pre-modern Japanese word closest to the meaning of the modern English craft, most craft professions were designated by the ideogram工 (kô) preceded by media. For example, a potter would be called tôkô 陶 and a lacquer worker shikkô 漆工, therefore indicating the centrality of the material for the practice, appreciation, and understanding of these different art forms/ skills.

Finally, the Portuguese word artesanato comes from the Latin word ars, which also conveyed the meanings of “skill”, “technique”, and “talent”. Because of the Eurocentric separation between art and craft that took place in the modern era, artesanato still has a negative connotation, denoting an amateur, low-skilled type of work, often engaged in by women as an income supplement. Thus, most educated craftspeople in Brazil dislike the designation of artesão or artesã (craftsman and craftswoman, respectively) for themselves.

That is why, exactly 60 years after the arrival of the first official Japanese immigrants in Brazil, a community of Japanese craftspeople, most of whom had arrived after the war, chose the word kôgei instead of craft or artesanato to name their association and annual exhibition aimed at promoting Japanese crafts in their new country of residence.

The Kôgei Art Association was created in 1968 to educate the Brazilian public about “authentic” Japanese traditional crafts. However, when the Japanese Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko visited Brazil in 1997, some thought it would be better to change the name in order to highlight the assimilation, adaption, and influence of Japanese immigrants in their society of reception. It was veteran potter Shoko Suzuki who suggested that they changed it from Kôgei to Craft:

I remembered that word from William Morris. He was interested in a high level of handicrafts […]. For me, craft is more international than kôgei. Kôgei is a Japanese thing. […] The reason why we came to this country was not to “be Japanese” or promote Japan. We need to enter Brazilian culture.

Shoko Suzuki (Tokyo, 1929-) had immigrated to Brazil in 1962 after watching a television program on the Japanese national broadcaster NHK about Brazil. The show displayed images of the now-scarce virgin areas of the Amazon Forest and the capital Brasilia, built in a deserted region virtually from scratch, in an ambitious design project by modernist architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012). Those images fed the artist’s desire to leave Japan, after having experienced the horrors of the Second World War, and gender discrimination. She longed to start somewhere anew, somewhere where a rigid tradition and social norms wouldn’t constraint her freedom and creativity. As a woman in post-Occupation Japan, she had had to overcome barriers to find a master to teach her ceramics. At renowned exhibitions such as the Tôtôkai, held by the ceramic art association of the same name founded by potter Hazan Itaya (1872-1963), she was the only woman amongst a group of forty male potters.

After watching the NHK show in late 1961, Suzuki rushed to put her house for sale and gather all the documentation necessary to undertake the official emigration process. She arrived in the Santos port of São Paulo state in Brazil, aboard the Argentina-Maru ship, in May 1962, after a two-month journey. Soon after, she rented a water-and-daub house in Mauá, countryside of São Paulo, where she started gathering and experimenting with local clays, feldspars, and ash glazes made from local plants and vegetables. In 1964, she and her husband, painter Yukio Suzuki, bought a house in neighbouring Cotia, where she immediately started to work on the construction of a Japanese traditional woodfired climbing kiln noborigama (brought to Japan by Korean craftsman in the sixteenth century after the so-called “Pottery Wars”). She used a kiln project that she had been given by a friend, potter Yoshikazu Shinoda, who had studied with Living National Treasure Yuzo Kondo, as a farewell gift. For materials, she used second-hand recycled bricks from the nearby Mizuno porcelain factory that had been set up by Japanese immigrants four years earlier. While building a climbing kiln was not a part of her initial plan, it turned out that the steep inclination of the terrain was perfect for it. She says:

I was not going to build a noborigama in Brazil. But my friend gave me his project, and in Japan, it was a very strict tradition. He was the student of a very important person (…). In those days, potters kept secrets, but he said: ” I will give you this kiln project because you are going to the end of the world”. Then, [after seeing the land] I thought: “I will use it”. The size of the kiln is small and the inclination [of the land] is exactly [right] for the kiln.

Shoko Suzuki and her husband, Yukio Suzuki, in front of her noborigama kiln named Saigama 彩窯, meaning coloring kiln, in Cotia, Brazil, in 1965. From the Artist’s personal archive.

In Brazil, clay has been fired by indigenous people that inhabited the territory to produce a variety of objects at least for 2000 years. Typically made by women in a domestic setting, it was hand-thrown, painted with a mixture of natural pigments, and fired at low temperatures of around 700°C in simple pit kilns. From the sixteenth century, with the Portuguese colonization, specialized potteries gathered around the coast, and clay was used for both construction and tableware by throwing at the potter’s wheel and firing in updraught kilns that reached about 1000°C. During this time, faience was brought from Portugal and, after the discovery of kaolin in Saxony in 1750, high-quality porcelain was also imported for the use of a few. From the mid-nineteenth century, with mass immigration from Europe, the production of industrial ceramics expanded, led by Portuguese and Italian immigrants, and boosted by new technology. In 1928, the S. Toyoda e Companhia Limitada porcelain factory was established in São Caetano do Sul by the first family of Japanese immigrants in the city, which functioned until 1981.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Theodoro Braga’s (1872-1953) decorative ceramics and Vitor Brecheret’s (1894-1955) clay sculptures have contributed to blurring the boundaries between art and craft transplanted with European colonization. Folk pottery, with strong ties to Brazil’s indigenous tradition, has also been reevaluated in its artistic and aesthetic qualities, with the most notorious representatives being Mestre Vitalino (1909-1963) and the anonymous craftspeople of Vale de Jequitinhonha, in Minas Gerais. More recently, women such as Lygia Reinach (1933-), Ofra Grinfeder (1945-), and Norma Grinberg (1951-) have brought together ceramics and conceptual art, and Kimi Niii (1947-) ceramics and design.

Japanese migrant craftsmen and women such as Shoko Suzuki, Akinori Nakatani (1943-), Mieko Ukeseki (1946-), Shugo Izumi (1949-), Kenjiro Ikoma (1948-) and others have had an important role in the expansion of functional ceramics beyond the realm of artesanato. They are responsible for the dissemination of Japanese techniques such as high-temperature wood-firing and natural ash glazing amongst both the public and practitioners. The hand-made ceramics boom that has taken over Brazil in the past decade has certainly sprouted from the roots they, and those before them, laboriously planted.

In 2006, Shoko Suzuki’s apprentice, Ivone Shirahata built a noborigama climbing kiln following the same design as the plan Suzuki received before leaving Japan, at her studio Terra Bela, named Akebonogama (meaning dawn). It is the third of its kind, after the original one built by potter Yoshikazu Shinoda in Nagano, named Metobagama, and Suzuki’s Saigama.

“I was so happy! I wanted to be in the middle. I wanted to learn by stepping on the floor, alone, absorbing.”

- Shoko Suzuki’s potter’s wheel

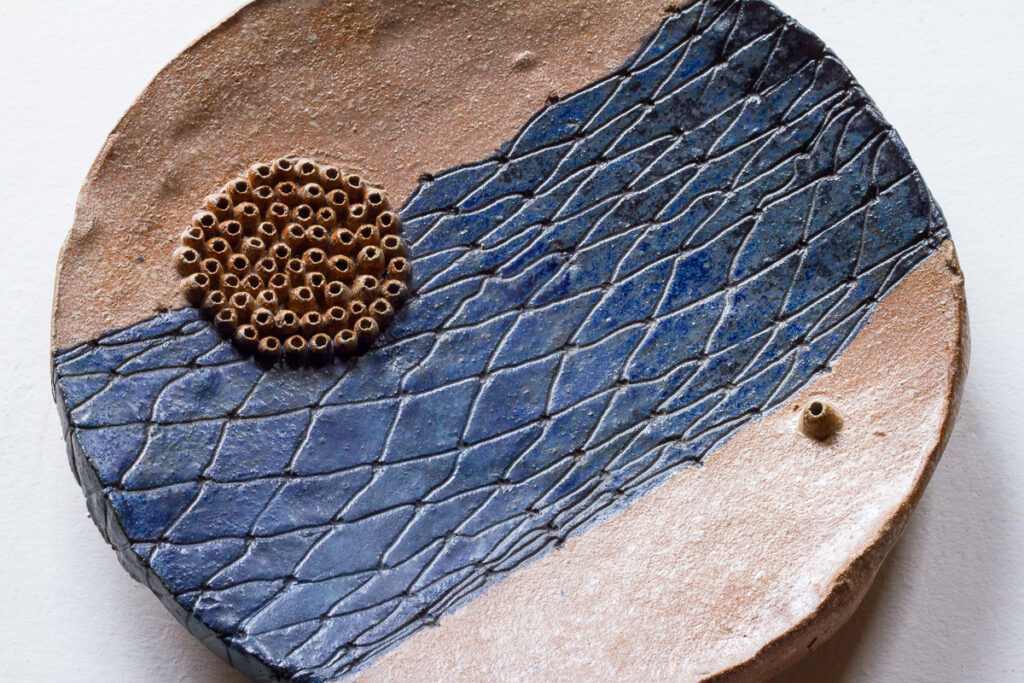

- Natural ash glazes in process of preparation

Shoko Suzuki spent two years doing clay and glaze tests in her new kiln before showing her work publicly. In 1967, she called members of the Japanese-Brazilian community to the official kiln opening at her studio, an event that ended up assembling a total of 800 people. In 1975, Suzuki displayed her ceramic work at a solo exhibition at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), one of the most renowned art museums in Brazil, and the first Japan-born ceramic artist to do so. In 1984, she finally had the opportunity to admire Niemeyer’s modernist constructions first-hand when she went to Brasília for an exhibition at the Federal District Cultural Foundation. And in 1995, she returned to Japan for the second time after leaving for Brazil, for a series of exhibitions in commemoration of the Centenary of the Brazil—Japan Friendship Treaty held at The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Art and other institutions around Japan. The exhibition was called “Contemporary Japanese-Brazilian Artists” and she was the only ceramicist in a group of 37 artists. In 2017, Shoko Suzuki received an Order of Merit by the Japanese government for her outstanding contributions to Japanese culture.

During one of her visits to Japan, an old potter friend, looking at Suzuki’s ceramic works at an exhibition, said that she was no longer “Japanese”. Suzuki laughed joyfully when telling me this story at her studio: “I was so happy! I wanted to be in the middle. I wanted to learn by stepping on the floor, alone, absorbing.”

This article is based on my Master’s Thesis titled Duas Mulheres Ceramistas entre o Japão e o Brasil: Identidade, Cultura e Representação [Two Women Ceramists between Japan and Brazil: Identity, Culture, and Representation], University of São Paulo, 2014. All Japanese names are in the order or Name-Surname.

About Liliana Morais

Liliana Morais holds a B.A. in Archaeology and History from the University of Lisbon (2007), an M.A. in Japanese Culture from the University of São Paulo (2014), and a PhD in Sociology from Tokyo Metropolitan University (2019). She is currently an Adjunct Professor at various universities around Japan. She was a curator of the exhibition From Japan to Brazil: the Voyage of Oriental Ceramics, held at Caixa Cultural Salvador. In 2014-5, she worked as a research collaborator at the Cunha Ceramics Cultural Institute, where she published the book Cunha Ceramics: 40 years of Japanese Ceramics in Brazil (ICCC, 2016, in Portuguese). As a researcher, she is interested in looking at art and material culture through the lens of mobility, transnational migration, and transcultural exchanges. Her scholarly work is based on qualitative research methods such as ethnographic fieldwork, participant observation, and oral history.

Liliana Morais holds a B.A. in Archaeology and History from the University of Lisbon (2007), an M.A. in Japanese Culture from the University of São Paulo (2014), and a PhD in Sociology from Tokyo Metropolitan University (2019). She is currently an Adjunct Professor at various universities around Japan. She was a curator of the exhibition From Japan to Brazil: the Voyage of Oriental Ceramics, held at Caixa Cultural Salvador. In 2014-5, she worked as a research collaborator at the Cunha Ceramics Cultural Institute, where she published the book Cunha Ceramics: 40 years of Japanese Ceramics in Brazil (ICCC, 2016, in Portuguese). As a researcher, she is interested in looking at art and material culture through the lens of mobility, transnational migration, and transcultural exchanges. Her scholarly work is based on qualitative research methods such as ethnographic fieldwork, participant observation, and oral history.

Comments

Adorei a matéria.

Hi Liliana, I am not sure if we met in Cerdeira Artist Village in Lousa Portugal this summer 2023 while I was in Marc Lancet’s workshop. I mentioned that I lived in Brazil when I was a young girl and now living in Ireland. Hope we can meet again in the near future. Warmest wishes, Mien