By contrast with the retail story, e-commerce promises to convey more of the stories of the handmade objects on sale. Aerospace engineer David Moorhead looks critically at its benefits for the craftsperson. To accompany this article, we will develop a listing of the major Indian e-commerce platforms and their particular innovations.

An aerospace engineer writing about craft, that seems a little odd, right? Well it’s true, my name is Dave Moorhead, I’m a 36 year old aerospace engineer who, through a Masters of Industrial Design combined with a passion for socially focused design, came to have an appreciation for the hand crafted, the act of creating it and the people around the world who have a mastery of the many different styles and techniques. I have two desires for this article. The first is to talk about how I came to have this appreciation for the handmade; and, second, to offer up some perspectives on craft, artisans and e-commerce that were the result of research for my Masters Degree. But before diving in, it’s important to acknowledge that, as a 36 year old, caucasian, middle class male, I unavoidably have a social and cultural lens that reflects my “western” upbringing. I don’t claim expertise and I acknowledge the limitations of my perspectives because of my background. Despite this limitation, it’s my hope that my perspectives, appropriately interpreted, are applicable by people of all cultures.

Before I did my post graduate study I’d never taken much more than a passing interest in craft or master craftspeople, i.e. artisans. I was an aerospace engineer who, whilst having an appreciation for “making” thanks to unconventionally creative and resourceful parents, had always been far more focused on problems, their resolutions and the physics of how things work. But in 2014, I was in the process of changing, of formalising a growing interest and passion for design and a desire to be involved in design that had an impact on people, not complex aeronautical machines. To do this I’d started a Masters of Product (Industrial) Design at Swinburne University in 2012 and it was through this lens of learning that I came to be doing a mini-thesis project focused on artisans. One part of which was to explore how to help artisans from places that still had a craft tradition (like India) to design more effectively for the e-commerce market.

To research this topic, I had read through many academic papers current at the time, reviewed a large number of artisan focused e-commerce websites, interviewed an academic expert in craft and cultural storytelling, interviewed the owner of an artisan focused e-commerce marketplace website, interviewed the leader of an artisan business and design course in Gujarat India and, met and interviewed 10+ Gujarati artisans who had studied design and business to help develop their skills and start their own businesses.

As my research progressed and my understanding of craft traditions in different countries developed, I was struck by the difference in inherent value that a crafted product seemed to have by comparison to a mass produced one. Whilst crafted products are equally intended to make money through sales, I learnt that they were imbued with a different “value” due to their provenance. Somehow their “story” allowed me to connect with their creation in a way I couldn’t with the mass produced. Whilst this concept wasn’t completely new to me having experienced craft markets in Australia, it took on new depths of meaning when considering countries that had their own unique craft tradition still in existence. This medium of crafted products seemed to communicate or record culture and values as much as mediums like art, music and writing.

This new understanding led me to explore further the important work of organisations like Kala Raksha Vidhalaya (KRV). KRV pursue a dual purpose of preserving the traditional craft forms and designs and helping artisans develop new skills to make a living from their craft. This dual purpose, that I came to realise was critical to the restoration and maintenance of a strong, relevant and valuable craft tradition, is often impossible for other organisations to pursue. This is because many working in this space are most focused on capacity building.

This higher level of understanding was balanced against a growing sense of the challenges of e-commerce. I was particularly influenced by the raw pragmatism and “facts of life” advice that came from my interview of an artisan focused e-commerce marketplace owner. This interview helped me step away from the dangers of a romanticised, patronising and paternalistic perspective on artisans and an unreasonably positive view of the benefits of e-commerce.

At the end of this research project my relationship with, understanding of and appreciation for craft, artisans and artisan-made products had completely changed. The most fundamental thing that I had learnt was an appreciation for the characteristics that sets a crafted product apart from the mass produced, i.e. the skill, culture and story of the person who invests significant time and passion in the making of a series of individual products that can richly reflect their culture and context. This understanding was cemented in my mind and heart after meeting many artisans in Gujarat. Having the privilege of interviewing them about their craft, its cultural tradition and their vision for its future was capped off by purchasing some of their work directly from them. Because of this experience and the story of their production and purchase these items have become artefacts of incredible value to me.

My research and experience in Gujarat left me with some personal insights and conclusions about what is lost and what is gained when artisans sell their products online using e-commerce as a transactional interface with local, national and global customers. Garland Issue 5 seeks to explore the link between storytelling in craft and its interaction with the market medium of e-commerce. My insights and conclusions will hopefully provide one perspective on what can reasonably be expected from the e-commerce medium in this context.

I will start with my perception of the limitations and downsides of e-commerce or “what is lost”. The most powerful insight I personally had when comparing my experience of reviewing artisan focused e-commerce websites with my experiences in Gujarat was that e-commerce can’t fully replace face to face interactions over craft. Why? I think it’s simply because we are social creatures, optimised for direct interactions and no matter how good the “digital” experience and medium is, it will never replace a person to person interaction.

This idea leads neatly onto the next limitation, that is, e-commerce’s effect on culture. My personal sense is that the online world and e-commerce, as one of its key marketplaces, tends to have a culture neutralising effect. In many contexts, this effect is desirable offering the potential for a globalised and thus a more uniform experience and exchange, greater opportunities, larger markets and more people to interact with. However, this effect seems to me to be a negative when considering the sale of craft online. It limits the story that a craft piece has by taking away the personal, social geographical and cultural context that the craft piece was created and sold in. A clear example of this for me is the certainty that I would not have the same love and appreciation for my handwoven silk scarf purchased from the artisan himself in his home in Gujarat as I did for one I purchased from an online store from my home in Australia.

The final limitation I found builds on the previous two limitations, that is, because e-commerce lacks the ability to create real interpersonal interactions and has a culture neutralising effect it cannot be the basis for supporting or developing a culturally important tradition of craft. These traditions need people, communities and place. This conclusion might seem obvious, but it was important for me because I’d seen and read many hopeful and hyperbolic reviews, articles and marketing spiels that hold up e-commerce as a likely saviour for craft traditions and for artisans struggling to keep making a living from their craft.

So what does e-commerce offer and how can these limitations be worked with? What is gained? Well, keeping the above limitations in mind, I think e-commerce is an essential market to be targeted by artisans. This is due to its universal convenience, low overhead, unparalleled local, national and global reach and its potential, when combined with social media and internet based messaging services, for multifaceted marketing and brand development.

Despite its limitations, I don’t believe that e-commerce should be ignored by artisans of any culture, just that it should be used by them with realistic expectations of its effectiveness as a tool that could serve their goals, both in business and the ongoing mastery of their craft. To do this I believe artisans need to design products specifically for e-commerce that maximise what craft can offer in contrast to mass produced products.

This doesn’t mean designing “westernised” or “culturally neutral” products, but it does mean designing specifically for the e-commerce customer demographics/characteristics within the limited customer interactions achievable. The challenge is to find ways to translate the richness of the craft art-form its cultural tradition and heritage, and the artisans own story and style, into products and product purchasing experiences that allow the customer to engage with the product’s provenance and perhaps the artisan themselves. These experiences should provide a taste of what the craft offers and act as a signpost for customers to seek “real” life interactions with the artisans.

One way a handcrafted product could effectively set itself apart and exploit the power of e-commerce is to find ways to weave stories into the product designs, both in how it looks and how it functions. The artisan might also seek to give the product the ability to form and hold new stories through its use and ownership. Why? My sense is that stories are a universal language of our humanness, compelling and attractive to us all. With storytelling technology now more widely available than ever before, artisans can create new craft product experiences by combining digital storytelling of themselves and their craft tradition with stories told through their craft.

My research of and experience with, hand crafted products and the people who make them has changed my personal perspective permanently and added a richness of understanding to my life. This experience also taught me something both obvious and yet often forgotten in writing about artisans. There is no “universal” way an artisan as a person can be characterised, nor a set of universal advice on how “they” should behave. There is a very real risk of being paternalistic and arrogant and this should be resisted. In my interactions with artisans of all cultures, I found each individual approaches the creation of the handmade from many different perspectives due to their personality, culture and socio-economic situation. These perspectives can often be ones that are pragmatic and unromantic, ones that don’t gel with the often romanticised view that we in the West so often apply to the tradition of craft and the manner in which craft should be created and sold.

Acknowledging all these limitations and risks, this Aerospace engineer turned craft appreciator sincerely hopes that the ideas, perspectives and reflections offered in this piece are of value to the continued discussion of the handmade.

Author

I’m an engineer and designer with a passion for socially focused design, who is currently living in Brunswick, Melbourne. Two years out from my Masters of Industrial Design I’m still working in the aerospace industry, but am in the process of starting down a new path more aligned with my passions and world view. I’m currently working on side projects in the Prosthetics and Orthotics industries along with designing and building my own furniture.

I’m an engineer and designer with a passion for socially focused design, who is currently living in Brunswick, Melbourne. Two years out from my Masters of Industrial Design I’m still working in the aerospace industry, but am in the process of starting down a new path more aligned with my passions and world view. I’m currently working on side projects in the Prosthetics and Orthotics industries along with designing and building my own furniture.

Platforms

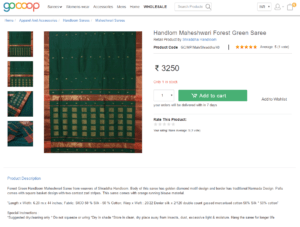

GoCoop – www.GoCoop.comInnovation: gathering together the handloom cooperatives into a common internet platform GoCoop is a platform for craft cooperatives, so it is dependent on them for information about the products. Products are linked to the cooperative and consumers can rate each product. Statement from GoCoopGoCoop is India’s first global marketplace for weavers and artisans and is the winner of government of India’s 1st National Award for Marketing of Handlooms (eCommerce). We at GoCoop truly believe that technology can drive social change. Our dream is to enable sustainable livelihoods for weavers and artisans through a simple, transparent online marketplace platform. We call this “Crafting Change”. At the same time, we deliver great service, good quality authentic products at best prices to our buyers. We are building the global marketplace with a great team of people with deep expertise in textiles, design, marketing & technology. GoCoop currently supports over 50,000 weavers and artisans through 250 co-operatives selling over 10,000 products. There is a wide range of exquisite handwoven silk, cotton & khadi sarees, dress materials, stoles, dupattas, home furnishings & men’s wear. The platform showcases over 50 handloom varieties from over 40 clusters that are an integral part of the rich cultural heritage of India. GoCoop, unlike other eCommerce portals, actually works closely with the co-operatives and community-based organisations at the grass-roots to enable them to sell their products online and also in managing the process of packing and shipping to buyers. GoCoop also supports the artisans through training and educational workshops. GoCoop’s unique development model is based on creating identity and awareness for Indian artisans and handcrafted products. The skills and capacity of the weavers and artisan co-ops are developed through training and other capacity development initiatives for improving the products and preparing the artisans further for eCommerce. The objective is to not only provide marketing linkage but also improve their quality and efficiency in the process. Over the next five years, GoCoop aims to empower a million weavers and artisans through the global marketplace.

|

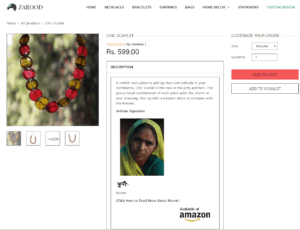

Zarood – www.zarood.com

Innovation: providing the personal philosophy of the artisan Zarood has the most extensive information about the makers of their products. When you click through the product, you find a link to the artisan. This includes not only a brief biography but also the artisan’s personal point of view. See example. Zarood claim to return 50% of the product cost back to the artisan. As well, 2% of the sale goes to their social foundation, Nav Chetna Seva Sansthan, which supports art forms in India. |

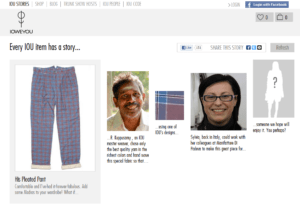

IOU Project – iouproject.com

Innovation: making the consumer visible in the supply chain IOU Project was one of the most innovative e-commerce sites. Consumers could click through to gather details about the Spanish artisan who assembled the garment and the Indian weaver who produced the cloth. The consumer was also encouraged to upload an image of themselves wearing the garment. It also recruited consumers to become Trunk Hosts, which would be events that gathered interest. The average cost was quite high, but the packaging included many tags that highlighted the imperfections as signs that the garments were authentically handmade. The website seems to have fallen into disrepair in recent times. |

Gaath

|

|

|

Comments

Very interesting and thanks for the references to the various online platforms.