- Ngozi Omeje, Connecting Deep

- Ngozi Omeje, Connecting Deep

Ngozi Omeje shares her journey through the soothing medium of clay and how it helps honour her family and inspire good works.

I reside and work in Nsukka, in Enugu State, eastern Nigeria. I make some of the ceramics artworks at home and in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts where I teach ceramics.

The local ceramic artists depend on exhibitions or commissions to sell their ceramic artworks. Sometimes, gallery representation is through art fairs. The traditional potters sell their pots in the rural markets and also traders buy for retail. They also get commissions from the bee farmers for quite a large number of pots.

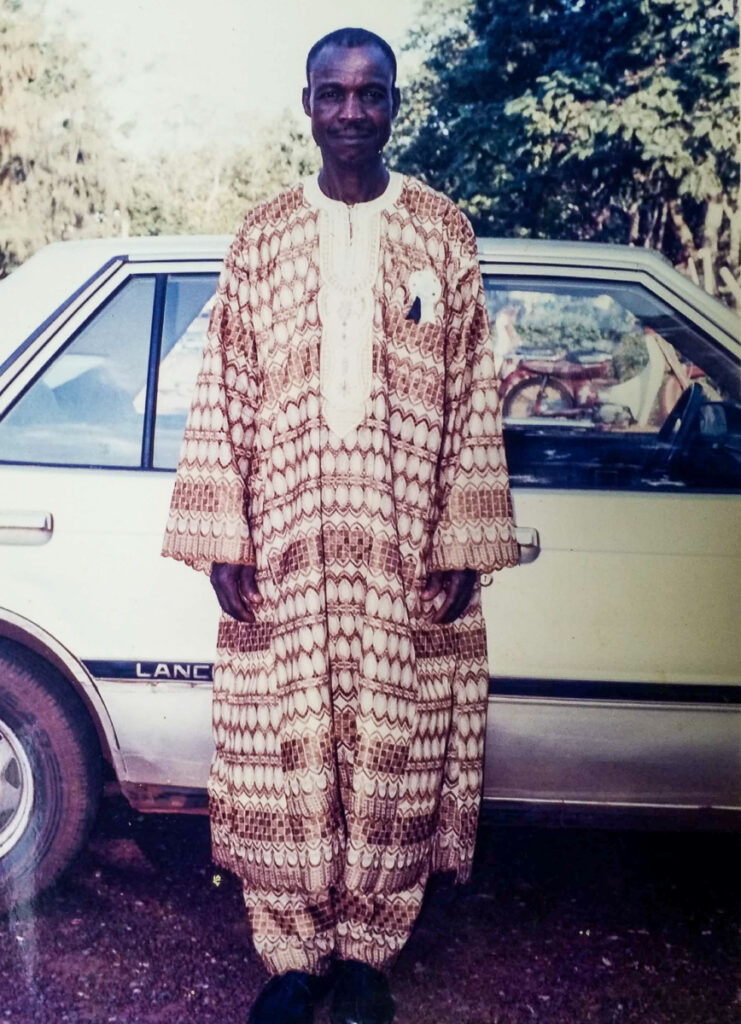

Fortunately, I was born a Gemini, on the 14th June 1979, to Lazarus Omeje’s family in Nsukka. Both parents were skillfully talented. My father majored in metal construction and my mother was an apprentice in a tailoring and weaving establishment while she conceived me.

My mother established her own tailoring shop after I was born. I grew up beside the foot pedalling sewing machine, playing with the offcuts. I attribute my creative ability to those exposures. I have tried sewing as a young girl, tacking offcuts together with stones to make pockets which could only hold its contents just for a while before losing up. Hammering pieces of cloth with stones to join them was a sign of creativity, producing to meet a need which was not recognized as such in those years.

✿

As a young girl, I remembered moulding a lizard with sand mixed with water. However, when the sand dried, I tried lifting up the lizard which disintegrated. Dismayed, my father informed me that there is a different type of sand used for modelling which is called clay. Patiently, I waited to get hold of clay since there was no deposit around my vicinity.

After primary education from the Central Primary School Isiakpu, Nsukka in 1990, I was admitted into Urban Girls’ Secondary School, Nsukka in 1991. Unfortunately, there was no art teacher for the junior class, so I chose the French Language. And there was no French teacher for senior class, I opted to offer science-oriented subjects, but was advised otherwise by my sister because of the inherent creativity in my family.

Thus, the story of my life as an artist began, having fallen in love with art in secondary school.

✿

In the year 2000, I gained admission into the University of Nigeria, Nsukka to study Fine and Applied Arts. Second semester of the first year, I was introduced to the long-awaited clay.

The cooling nature of clay was so temperate and the calming effects were extremely alluring. Escape became impossible. Specialising in ceramics was the only option. In furtherance of that, in 2004, I was introduced to ceramics exploration by Ozioma Onuzulike in a course, the Exploration of Indigenous African Ceramic Ideas, Forms and Materials. Ever since then, exploring ceramics has become my craving. Combining clay with found materials where necessary accentuated my statements.

✿

My first solo exhibition was in 2018 titled Connecting Deep featuring eight elephants. It was held in the Centre for Contemporary Art Lagos, Nigeria. I shared the idea with the founder of the Centre, Bisi Silver, about making an elephant that will be cut down by the audience as a separation rite of a loved one. She suggested that there are family members to mourn the departed, which means it should not one but several of them mourn the other that was cut down.

So, that’s how I decided to configure the number of my immediate family, which was eight. Recently, I wanted to include the extended family that gave support by adding to the number of elephants, but El Anatsui during a studio-visit suggested twenty in number. I am yet to get a space to exhibit them.

Connecting Deep is a herd of eight elephants composed of suspended leaves. The suspension was achieved through the use of strings that allowed me to draw in the audience, not just as spectators, but as co-creators of the installation. But the audience participation was articulated as a representation of something else: the administration of coup de grace.

It was a tribute to my father. The elephant is for me a figuration of my father whose accomplishments and personal attributes such as care, love and strength of will, are gigantic like the elephant. This also earned him the title of Oruimenyi (the strength of an elephant), given by his mother. All these came to a halt at the moment of his death. Not to say that the cutting of the leaves that form the elephant points fingers at people as the cause of his demise, the cutting suggests shared memory that will transcend into collective memory.

In traditional Igbo society, symbolic names attributed to the elephant are so many. Names like Ononenyi (someone on elephant), Enyikwonwa (the elephant carrying a baby), Udoakpuenyi (you cannot put a rope around the elephant’s neck), Nnabuenyi (the father is an elephant), Ohabuenyi (the community is an elephant) and so on. All these names point to the enormous strength of elephants. Aside from the strength, elephants share 60% emotional abilities with human beings. They celebrate birth, mourn and reunite after a long period of separation.

Symbolically, Connecting Deep is a re-enactment, using figures of elephants to close the gap or yearning for a departed loved one. It focuses on pulling experiences from others in the form of narrative.

The production processes were documented as well as the separation rite. So the pile of clay shards will be in grave-like form. The grave that holds the energy of the departed and is being remembered by the legacies left behind. His legacy for me is with the grits he taught me through hard work. The documentary of the elephant playing alongside the grave will connect to the audience as they internally pictured memories of their love.

✿

My involvement with the international ceramic scene with Dionne Haroutunian, the founder of Sevshoon Art Centre, who came to my department in Nsukka for a printmaking workshop supported by the US Embassy. It was during the workshop that she saw my installations during our MFA final assessment that happened the same time with the workshop. Thus, she invited me to make a permanent installation at the Centre in Seattle, USA.

✿

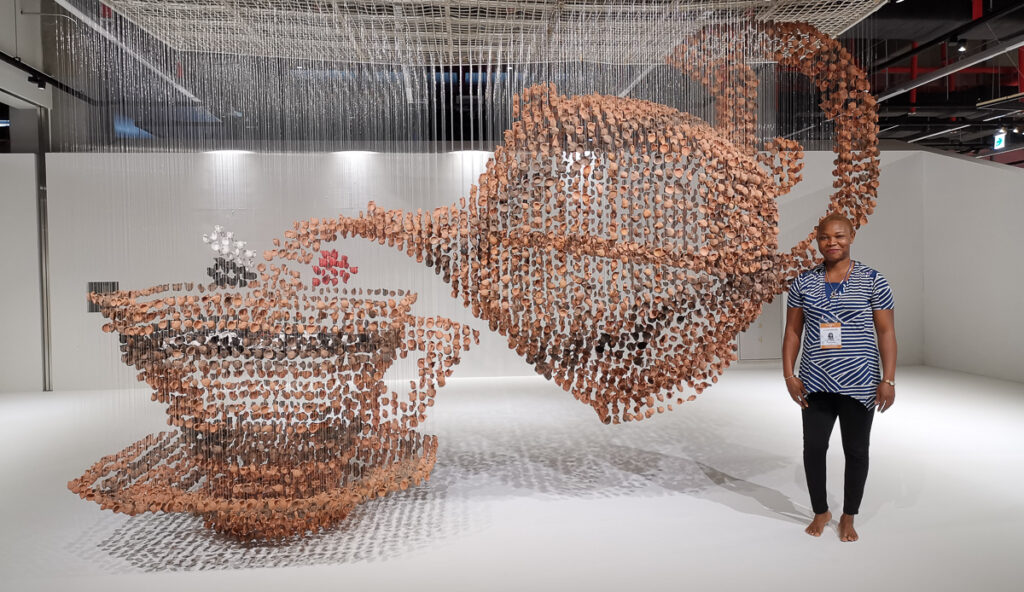

Last year I was invited to show at the Cheongju International Craft Biennale. Think Tea, Think Cup is configured with thousands of tiny cups. Together, these tiny cups fashioned a single big cup with a saucer and a pouring teapot through suspension.

Think Tea, Think Cup discusses passions, dreams and individual’s driving goals. The artwork is motivational in context as well as symbolic. Its metaphoric symbolism interrogates the micro efforts, despair and hope, rise and fall, all the interludes that accumulate into macro wins, successes or dreams accomplished. The content, tea, symbolises our dreams. And the container, teapot and cup, symbolize the rigorous journey before attainment of dreams.

Think Tea, Think Cup will make clear to the audience that they are their own genie. A single step makes a difference to our destination. It must not be a straight-line journey: continuous movements to the goals will lead us there.

✿

The Nigerian traditional pots that I would like to revive are the ornamental pots of Ehandiagu and Nrobo pottery communities, both around my locality. Since the widespread of Christianity, these ornamental pots which were largely adorned with decorative accessories have been abandoned. They were abandoned because they are decorative items for the traditional worshippers’ altar.

So I am particularly interested in these items because of the aesthetics lost to the fear of pagan worshipping. Inherently, if I reform the shape of the pots and use the same decorative accessories, then I will be able to reconnect to the eroding pottery forms in a contemporary way.

✿

Ehandiagu Honey pot with the cover

Because of the hot weather in my country, fired clay in the form of ceramics has a soothing calmness for the bees. This is the singular reason why pottery making for the traditional potters is very lucrative. However, the firing temperature of these pots is low; they are fired between 460 and 510-degree centigrade through open firing. Most of the pots are lost during honey harvest because the farmers have to crack the pot to access the honey and also kill the bees through an open flame.

Thus, having considered the calmness of the clay pot, I plan to make a pot that can be open in half with two side pockets. Opening the pot in half will allow the honey to tumble out in a ball-like form and the bees will be in the pockets during harvest. Therefore, you need not smoke nor kill the bees to harvest the honey. The ball-like mass of honey (the sphere) informs the name of the beehive which is still under design –Honey Ball.

Author

Ngozi Omeje teaches at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Her work can also be found in the [Re]-entanglements exhibition. Ngozi can be found on her Facebook page and blog.

Ngozi Omeje teaches at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Her work can also be found in the [Re]-entanglements exhibition. Ngozi can be found on her Facebook page and blog.

Comments

This was brilliant. Thank you so much for sharing your story and journey. I am very inspired even more because I am planning a pottery exhibition inspired by pottery in Nsukka and will soon embark on a research excursion to Enugu. Thank you for sharing your work.