Khanya Mthethwa

Khanya Mthethwa transforms the traditional Zulu girdle into a fashion item for proud South Africans

This is a peer-reviewed publication written according to academic standards.

As an isiZulu-speaking researcher, I chose the isifociya (girdle) body adornment for study because I wished to identify with the historical cultural practices involved. The isifociya as an object of study and emulation became the focus of my interest, following my experience of observing a female relative tying a scarf around her stomach after childbirth (similar to Figure 3.1). Upon conversing with my mother, I was made aware that this ritual was initially performed with a grass object. However, due to my mother’s Christian beliefs and upbringing, she had limited knowledge of the in-depth meanings associated with the object. Therefore, it became a personal imperative for me to understand the use and symbolic meaning of isifociya, to position myself within a particular cultural identity as an isiZulu-speaking woman. I thus set out to collect the necessary data from both archival sources and through interviews with individuals, considering both the backgrounds of, and influences on, the participants in order to extract relevance.

History of Isifociya

This paper is based on the notion of a post-colonial revival of isifociya, through historical investigation and an attempt to reassert the relevance of an indigenous culture. Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin (2000:168) argue that post-colonialism deals with the effects of colonisation on cultures and societies. Following their lead, I develop the potential of a post-colonial revisiting of a particular tradition of female adornment among isiZulu-speakers. I do this in order to position my own creation of contemporary isifociya adornments.

In addition to a consideration of the literary sources which deal with the practices associated with female adornment, I interviewed two participants in-depth. The first participant was an elderly married Mrs Nyandeni, a 70-year-old isiZulu speaking woman, born in Kwa-Zulu Natal in Nongoma at the Maye village. She is the key informant for this study based on her knowledge of cultural practices. The second participant was a married elderly woman who makes traditional adornment objects. Information was obtained through one-on-one interviews, specifically focusing on the process of making isifociya as well as visuals in the form of photographs and videography.

Figure 1.1 Artist unrecorded, Zulu, South Africa (Msinga region image). Isibhamba/Ixhama (Married woman’s belt). Date unrecorded, acquired 1992. Fibre, beads, brass studs. 7 x 71 cm. Accession number: 1992.09.013. Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum).

Isifociya has not always been an item embellished in beads. Originally, isifociya was only made from grass that was plaited or twisted. According to Nyandeni (2018), isifociya was made from grass that women would manipulate into a belt panel (Figure 1.1). She recalls that there are four different types of grass from which it was made: Isikhonkho, umuzi, incema and ikhwane. Nyandeni (2018) verifies that isifociya was initially made from grass when she mentions that beadwork on isifociya only began when indigenous people began using isifociya as an accessory, and decorated it for use with traditional attire. Figure 1.2 is isifociya (beaded waist panel) currently housed at the Wits Art Museum, which originates from uMsinga region in Kwa –Zulu Natal. The Msinga pattern is a repetition of a triangle motif which grows bigger with each different colour. There is also an inclusion of small arrow shapes in three different colours. The isifociya is embellished with domed brass studs on either end of the belt, which sit on twisted grass which has been stitched together.

Figure 1.2 Artist unrecorded, Zulu, South Africa (Msinga region image). Isibhamba/Ixhama (Married woman’s belt). Date unrecorded, acquired 1992. Fibre, beads, brass studs. 7 x 71 cm. Accession number: 1992.09.013. Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum).

Mayr (1907:638) identifies isifociya as the girdle worn (by women) around the chest and body made of grass or beads (ixhama). According to Bryant (1949: 44), isifociya is a girdle worn by Zulu women after marriage; however, (he continues) when she becomes a widow her isifociya is burned, and she will no longer wear one. This serves as a symbol to the public that she is single and has the potential to re-marry. However, Nyadeni (2018), speaking of her understanding of traditional practice, claims that when a woman became a widow, she would wear isifociya in order to acquire courage and wisdom needed for her to run the household independently.

Isifociya had multiple uses, each deemed important to the wearer. According to Nyandeni (2018) if a woman appeared to be infertile, she would tie isifociya as a prayer item to request the ability to bring life into the world. Nyandeni recalls that a woman would wear isifociya even when she encountered marital problems, upon which her elders would advise that the bride use isifociya as a prayer item. When men had gone to war, married women were expected to tie their isifociya as a means of praying for the men’s safety, so they were not wounded or killed in battle. Therefore, “isifociya was like a bible that the women relied on as means of prayer” (Nyandeni 2018).

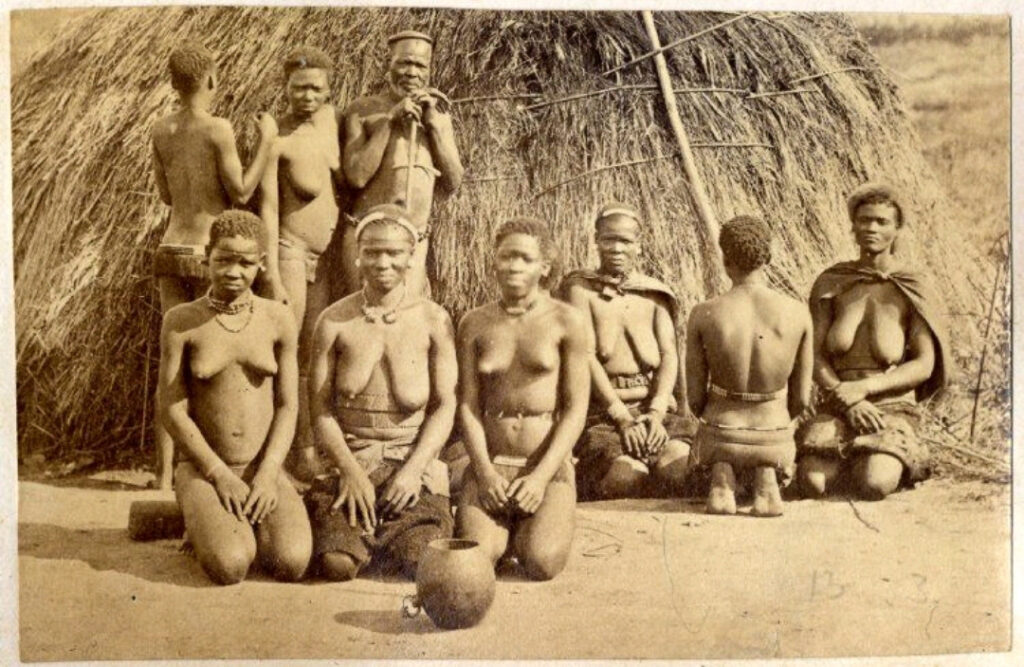

Figure 2.1: Photographer Unknown. Family Group, Natal. 1800s. Silver Gelatin Print. 1080 x 703 cm. Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town.

Figure 2.1 depicts an isiZulu family posing in front of an indlu (dwelling) hut. The beaded adornments worn by the women are identification markers that distinguish the different stages in their lives. In this image, isifociya is shown as integral to everyday life. Considering that the women in the photograph are both young and old, and wearing adornments that vary; I will attempt to give a description of the different stages in a Zulu woman’s life in relation to waist panels.

Figure 2.1 illustrates only one elderly male wearing isicoco, who may be the husband surrounded by his daughters and wives. The image depicts five girls, each identified by a string of beads with square beadwork covering their lower bodies, or wearing a loin dress with fringes. Of the five girls, one is dressed in a cloth instead of a fringed loin dress. Mayr (1907:634) explains that when a girl wears a string with one square piece of beadwork as a loin dress, this is called isigege—this can be identified in the girl standing next to the old man and the girl on the left-hand side in the front row. Mayr (1907:636) further elaborates that as the girls grow, so does the size and kind of loin dress they wear. One of these, called umaydika or isiheshe, has fringes and is the same size as the square beadwork piece. The isiheshe is a fringed girdle made of strings with a bead border—seen on the girl on the far left side of the old man and the one in the front, on the right side of the married woman. Nyandeni (2018) argues that girls, who are in their maiden phase, wear umutsha (loin cover) as a signal of their status as unmarried, and toddlers would wear umginqo (apron girdles) made of imizi during times when there were no beads. Marilee Wood (1996:158), however, states that umutsha is a name that applied to all types of loin covers worn by both sexes during puberty onwards, but the construction of umutsha dictated which sex the beadwork adorned.

The girls, who wear the small fringe girdles, wear these as signifiers of the phase before puberty. However, girls who reach puberty begin covering their bodies from the waist to their knees with a cotton blanket (Mayr 1907:1936). This is evident in Figure 2.1 on the girl kneeling with her back towards the camera. Two of the girls are wearing what appear to be belts, made using the rolled umbhijo technique, but smaller in width compared to those worn by the married women. When showing this image to Nyandeni (2018), in an attempt to gain more understanding on how these waist panels differ, she explained that only girls who have reached puberty who would wear this type of waist strip.

Bryant (1907:610,622) claims that a pregnant bride would wear bound over her chest an apron (isiDiya) made out of duiker-skin concealing her breasts and abdomen, this she would wear only once and only during her first pregnancy. Once the woman has given birth, isiDiya became a sack which the mother would use to carry her baby on her back. Mayr (1907: 640) argues that a Zulu bride would wear an apron (umbodiya) of buck or goatskin, until the birth of her first child.

The married woman in the middle, in the front row with two girls on either side of her, wears isifociya wrapped around her stomach twice. According to Bryant (1907:613), the reason she wears her isifociya this way can be attributed to the fact that, following childbirth, woman would be tightly bound twice around their abdomens with rope (umKandzi) of plaited umTshiki grass. Once the umbilical cord of the baby had fallen off, the woman would remove her umKadzi band and replace it with Umqila (a temporary isifociya). Mayr (1907:613) states that for a period of two or three months the mother of a newborn abstains from eating certain foods until further notice from the elder wives, who alert her when this waiting period is over. It is during this period that she must discard her umqila waist belt and wear an isifociya newly made of grass. Nyandeni (2018) argues that a woman was instructed by her elders to wear isifociya as means of maintaining her figure and physique, and for the woman to regain her strength after losing blood during childbirth. In Figure 2.1 the women at the back on the far right corner are wives who have their shoulders covered with a cloak called ibhayi.

Isifociya and the body

When one dresses the body, this process entails a number of actions that can be considered as ritualistic behaviour. As a form of ritual practice, a married woman ties isifociya for the first time as a wife, thereafter she wears it on a daily basis reflecting the ritual in the form of a routine. This research provides an analysis which explores the behavioural patterns associated with the wearing of isifociya by isiZulu women. Isifociya was traditionally worn on the body from morning until the evening. A woman would wear isifociya with the understanding that it forms part of her role as a wife in her household, but it also came with her acknowledgement of tradition. As a wife forms part of a larger community, a woman would adhere to the social constructs of her community to avoid being labelled an individual with ill intentions, thus she would wear isifociya as means of protecting her household (Nyandeni 2018).

Therefore, isifociya becomes more than just an object, but an object which communicates a women’s social status, and becomes entrenched into her very being. Isifociya would serve as a marker which associated the female body with body adornment rituals and a specific indigenous cultural or linguistic group. A woman’s body movements were not restricted by isifociya, although wearing it for the whole day would leave imprints and lines on her stomach. These imprints become evidence of the object encountering the body, and serve as a recollection of the body’s lived experience. It is only when isifociya was worn “out” that it would cause physical discomfort for the wearer. However, backing it with a cloth, as seen in numerous museum examples, would remedy this problem (Nyandeni 2018).

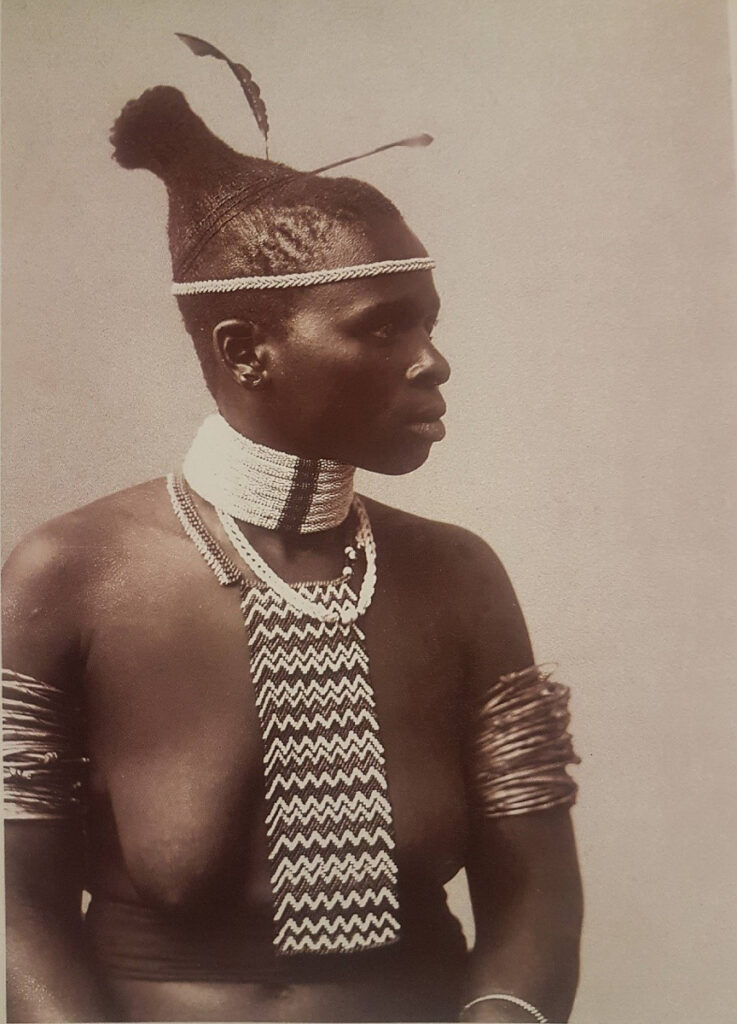

Figure 3.1: J.E. Middlebrook. Studio photograph of a married Zulu woman. 1880s. Beads, Grass, metal bangles, cloth.541 x 884cm. (Photograph courtesy Museum Africa).

Being a contemporary jewellery designer, I explore how a particular form of Zulu adornment may be used in the contemporary context. Because there is limited documentation of pre-colonial cultural practices and adornments of the Zulu people, I have tried to develop a means of translating the knowledge I have gained through my research using contemporary jewellery techniques. Nyandeni attributes the change in traditional ways of dress and cultural customs to Christianity, which was introduced to indigenous people via colonialism and which is evidenced by my mother’s lack of knowledge. Her answer to the question: “What do you think is the cause of loss of cultural practices like the wearing of isifociya?” was: “It is definitely with the arrival of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus Christ which encouraged us to lose our traditions” (Nyandeni 2018). Before answering this question, Nyandeni shared her regret for the loss of cultural practices.

This response, therefore, shows that despite post-colonial changes, the cultural practice of isifociya is important to the preservation of the knowledge of Zulu cultural practice. In an attempt to work towards a cultural revival and re-discovery of one’s selfhood, the course of decolonisation begins. Nayar (2008:3) claims that decolonisation is the process whereby non-white nations and ethnic groups in countries such as Africa strive to secure freedom (economic, political, and intellectual) from their European masters. Decolonisation seeks freedom from colonial forms of thinking, to revive native, local and vernacular forms of questioning, and the capsizing of European categories and epistemologies. Biko (1978:70) states that the traditional inferior-superior black-white complexes are a deliberate creation by the colonialist. Biko (1978) furthers explains how, specifically in South Africa, national consciousness must fight a number of dynamics (traditional complexes, the emptiness of the native’s past and the question of black-white dependency, to name a few) in order for a noteworthy revolution to occur.

The debate as to whether human artefacts generate meanings that are salient in a culture, or whether a culture creates artefacts which represent the types of meaning it gives to events, is reminiscent of long-running controversies in psychology (Smith & Bond 1993:36). Despite these debates, this research presents an artefact located in the history of amaZulu which has over the years transformed, as to the way in which it is both made and worn on the body. It is this change which requires further investigation.

I analysed texts from Achille Mbembe (2015), Ngugi wa Thiong’o (2004) and Steve Biko (1979) to examine the cultural context of decolonisation in the post-colonial space. Furthermore, I considered perceptions of self and the environment as raised by Vukile Khumalo (2000), Thiong’o, Mbembe and Biko in relation to decolonisation and the post-colonial. For this paper, I gathered data using specific methods and, as a designer who is bringing her own skills and ideas to the process of collecting data, I participated in practice-led research. Practice-led research forms part of qualitative research. The methods used to collect data for this research included interviews and a survey.

In an attempt to recover aspects of a particular cultural heritage, decolonisation becomes the point of departure for this paper, by analysing how colonialism influenced changes in the elaboration of existing cultural practices among amaZulu. This provides a useful framework for this research aimed at reinterpreting aspects of Zulu heritage through adornments. Colonialism provided opportunities for settlers to examine the “others” among whom they were located, and allowed them a prerogative to document the lifestyle and events that occurred in Africa, mostly from their own perspectives. Unfortunately, this also meant that these Eurocentric accounts are often skewed, and crucial information was often omitted, missed or discarded.

The term “Eurocentric” refers to the notion of a worldview centred on European civilisation. Mbembe (2015:9) questions what being “Westernized” means. He defines Westernisation as a canon that characterises the truth in a way where the production of knowledge neglects other epistemic traditions. Such epistemic centrality is seen in many phases of cultural production in a globalised modern world. Therefore, his definition of Westernisation is an archetype that centres knowledge and culture on a Eurocentric epistemic principle (Mbembe 2015:9). Lisbeth den Besten (2011:18) argues that the origin of Western jewellery can be attributed to the use of specific materials and techniques, for example, how gemstones are set and included in jewellery pieces. However, we tend to overlook the fact that there has been a multitude of influences on European jewellery over the past five-hundred years that make it difficult to define or assert it as “Eurocentric” in style.

Contemporary jewellery, framed in a Eurocentric context, is beyond the postmodern. Den Besten (2011:18) argues that “contemporary jewellery” implies that it has been made now and of our time, whereas the term actually covers a period of time spanning at least forty-five years, and this assumption is therefore imprecise. Contemporary African jewellery designers appear to associate authentic jewellery with design specifications that are of European style and manufactured in precious metals. In contrast, the jewellery examined in this paper is made today using materials that do not conform to the dictates of the European canon, by using Zulu adornments and the identity markers associated with the Zulu people as its source. It becomes imperative to discern what defines my jewellery as South African, and what cultural influences I am drawing from to arrive at designs that have a South African aesthetic.

Therefore, as a South African and isiZulu-speaking designer it is important to me to use sources that are located in my own cultural context, which inform my designs and expand my understanding of indigenous knowledge around jewellery. I make modern or contemporary jewellery with a South African (specifically Zulu) aesthetic that includes an understanding of how the jewellery relates to the human body. Carol Boram-Hays (2015:29) emphasises that in order to maintain their culture, the indigenous people from Nongoma have realised that their traditions must remain relevant by being flexible enough to reflect the lives and concerns of modern people. The concept of contemporary jewellery according to Den Besten (2011:15) goes beyond the preconceived notion that contemporary only involves the traditional baubles, bangles and beads, but extends to photography, installations and performances. The intention of this project is, therefore, to design and make jewellery that will be worn and exhibited on a human body through performance.

Concerning the interviews for this study, the proposed study population for investigating traditional aspects of the isifociya was initially limited to four married women between the ages of 45 and 70, chosen on the basis that varied responses founded on age differences would be attained. However, only two women participated. These interviews were semi-structured. Participants were chosen with the understanding that they are knowledgeable in cultural practices and keepers of the community’s traditional customs. The choice of participants’ locations was based on where Zulu history might still be traced.

The participants spoke of cultural practice and how cultural values defined the function of isifociya. It became evident that a woman in her role as wife, and her ability to bear children, cannot be dissociated from the occasions which mark the wearing of these belts. When Nyandeni was asked what other functions isifociya had besides that of being worn after childbirth, she explained:

Even when she became a widow, a woman had to wear isifociya in order to acquire courage and wisdom needed for her to be able to run the household.

From Nyandeni’s response, one can derive how cultural practices are carried out in accordance with social constructs of a married woman’s role in her household. Isifociya serves as an object that is integral to her role as matriarch, and from which she draws strength. There is a level of responsibility and power attributed to a woman’s role, which is respected and reinforced by her elders.

Stereotypes and the body

In an effort to preserve their culture, amaZulu incorporated materials accessible to them, and integrated these into their traditional attire. It would seem they adapted their ways of dress as a form of resistance to colonialism, and as a celebration of their cultural identity. The use of isifociya as a source of inspiration for this study presents an opportunity for me to use the object as a tool, which allows the body to inform the jewellery-making process. The use of isifociya is culturally inclined, and the wearer’s experience of it can be attributed to how the body carries the object. Thus isifociya can be translated into a contemporary ornamental jewellery piece by locating it within an art jewellery design category. Jivan Astfalck (2005:23) argues that,

Behind every art jewellery piece object, stands a “speaking person”, who is constantly involved in dialogue with the world around herself. Art jewellery is perfectly placed to explore and communicate the nature of our conflicted existence, as well as the pleasure of being alive. This is because of its intimate relationship to the physical and cultural body.

Isifociya is associated with Zulu culture, which is rooted in a past previously perceived by Europeans as “primitive” and “exotic”. This cultural object is thus loaded with symbolism, history and indigenous identity that demands for a sharing of the history entrenched in it. Astfalck (2005:19) argues that in order for jewellery as an art practice to exist, it must be associated with the historical and traditional roots found in its materials and processes, adornment and ornamentation. The history associated with Zulu beadwork, according to Nettleton (2014:96-98), indicates that beaded objects sometimes included waste items of Western manufacture which were used to create forms of resistance and cultural persistence. These items were more prevalent among indigenous people who interacted with the modern machinery of commerce. They differed from those who remained in the villages as they wore items that absorbed Western influences. These beaded items, therefore, served as markers of migrant identity alongside more traditional forms of beadwork (Nettleton 2014).

Therefore, the translation of isifociya into a contemporary jewellery ornament gives the jewellery a significance which surpasses the superficial. Art jewellery utilises the human body as a catalyst for meaning. It is not restricted to being worn as a status symbol or as an object of delight, but for purposes of transmitting meaning or content, similar to the manner of fine art. However, it differs from fine art in that its meaning is physically carried by a human body (Besten 2011:60). The unification of fine art and jewellery presents an opportunity for me to create and decide on an end product, and which site of the body the object will adorn. Astfalck (2005:20) suggests that art jewellery does not address histories informed by other art disciplines, but that the jewellery object is a framing device for these disciplines. Therefore, my end product will encompass the cultural aesthetic of isifociya and use it as a framing device which integrates traditional jewellery techniques.

However, the challenge was whether the resulting piece of jewellery could be deemed wearable or not. Using isifociya as a point of reference provided a framework from which to work, concerning design aesthetic, materials, shape, scale and comfort. The challenge was to produce pieces that achieve wearability like that of isifociya, but also allows for body movement, although the design may constrain the body to some degree. How one perceives the body dictates the way in which a subject may view the object. This allows the body to transmit and add meaning to the piece. According to Besten (2012:125) the French philosopher Maurice Merleau- Ponty is of the view that the body is not an object, but the subject itself formed by the lived experiences of the body’s senses.

The making of a contemporary Isifociya

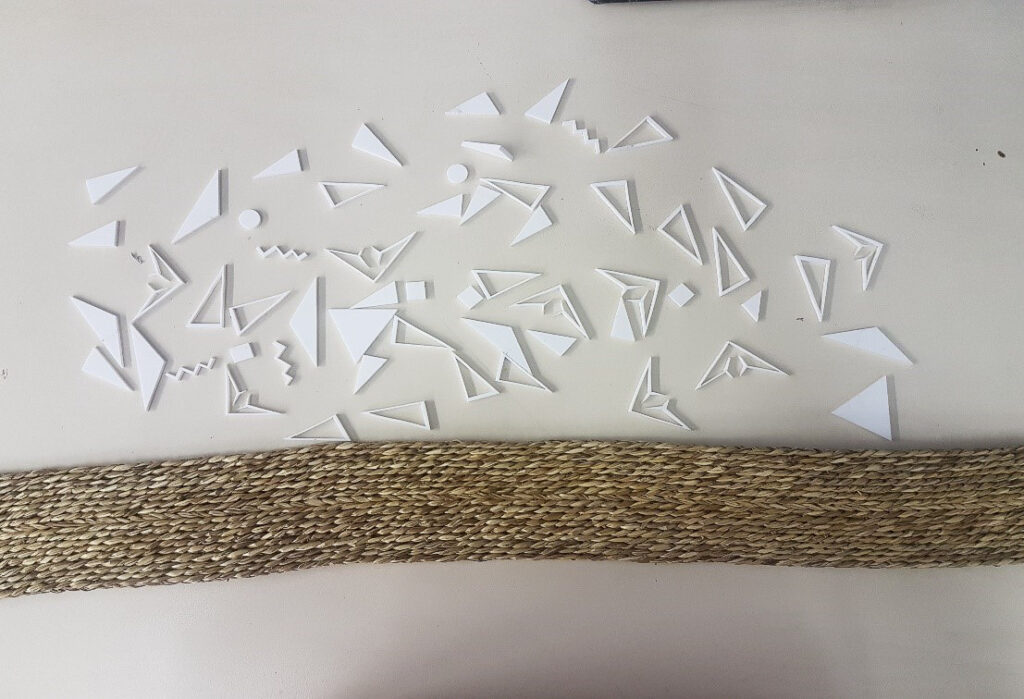

Initially, this experimental process began with an attempt to incorporate techniques which involve the use of technology, however, the theoretical literature and my research findings gradually led to a different approach. The first experiment uses laser-cut perspex pieces which are geometric in shape. The images below illustrate the various stages of my experimental process. The aim was to gauge the aesthetic appeal of attaching perspex on isifociya. As pleasing as the incorporation of perspex is to the eye, the designs would need to be developed to ensure that attaching the pieces would not be untidy, and would be adaptable to the movement of the isifociya belt on the body.

Figure 3.7: Nokukhanya Mthethwa. isifociya. 2018. Grass and perspex cut-outs. 4032 x 3024 cm (Photograph by author).

Figure 3.8: Nokukhanya Mthethwa. Isifociya. 2018. Grass and patterned perspex cut-outs. 4032 x 3024 cm (Photograph by author).

Second belt–Silver Buckle Isifociya

To the second belt, I added a silver buckle element. I felt this would reference Eurocentric approaches and therefore fit well into a contemporary era. However, in retrospect, I questioned if this element was contradictory in the context of my research. Making metal the dominant material on this belt would conform to the idea of ‘contemporary’ denoting being about specific techniques or metalwork. As a result, for this belt, the silver elements were discontinued and only the buckle remained as a silver component. In doing so, the grass remains dominant and the buckle transforms the isifociya into a fashionable piece without overpowering the main material.

Figure 3.8: Nokukhanya Mthethwa. Isifociya. 2018. Grass and patterned perspex cut-outs. 4032 x 3024 cm (Photograph by author).

Figure 3.12: Nokukhanya Mthethwa. Completed Isifociya belt. 2018. Sterling silver, grass. 4032 x 3024cm (Photograph by author).

Third belt – Cowrie Shell Isifociya

The concept for this belt gave rise to the idea of using found objects, which correlates with my research on redefining contemporary art jewellery. In a South African context where our economy is largely unstable, people may opt to acquire found materials which are easily accessible and affordable. Therefore, regardless of the influence of theoretical literature on my design, it is important that the materials I use in developing my jewellery are well-considered. Furthermore, utilising cowrie shells allows the object to appear a predominantly indigenous cultural item.

Figure 3.13: Nokukhanya Mthethwa., Cowrie shells and grass. 2018 (Photograph by author).

Figure 3.15: Nokukhanya Mthethwa. Sewing on the string. 2018 (Photograph by author).

Figure 3.17: Nokukhanya Mthethwa. Completed cowrie shell isifociya, 2018. Cowrie shells, sterling silver granules, grass. 4032 x 3024 cm (Photograph by author).

The process of constructing these pieces allowed me to activate a cultural consciousness, in acknowledging indigenous peoples as my source of inspiration. As a modern Zulu woman, my involvement in the making process adds an element of the contemporary. However, my use of materials and my consultations with Zulu participants are methods which ensured the ethnicity of the pieces. One may argue that an object is activated when the designer’s identity becomes the central focus of meaning in the piece.

Meaning is generated through symbolic systems of representation, how identities are produced, consumed and regulated within a culture activates that meaning (Woodward 1997:2). Within the process of making, the way in which materials are processed may add valuable meaning to the piece. While making the pieces, there were conflicting notions as to how I could reinterpret isifociya as a cultural object, since in my institutionalised training, jewellery is commonly identified by its use of precious metals. This is not to say that as a designer within an educational institution I am obligated to conform to Eurocentric views in my jewellery-making. Nevertheless, I have been indoctrinated to believe that when I draw inspiration from my cultural identity, I must remain cognizant of the fact that the pieces need to be palatable and sellable within a Eurocentric market.

It is through the perspective of decolonisation that I become fully aware of my influences as a designer and the intricacies embedded in my cultural affiliated identity; that I am able to develop pieces that embrace and revive the notions of black consciousness. In order to re-imagine isifociya I needed to gain a better understanding of my culture.

Understanding the body affords the designer a vantage point to bridge the gap between orthodox jewellery and art jewellery for the consumer. The aim is thus to create pieces that place comfort at the forefront, to ascertain that individuals who adorn themselves with the finished product do not feel hindrance in their movements, which may affect their daily routine. One may argue that the girdle encourages dependency on the object. This involves a process of socialisation whereby an individual comes to psychologically rely on a cultural object and its purported benefits. Nonetheless, transforming isifociya into a fashionable belt provides the wearer with the option to wear it however they see fit, without feeling constricted.

Adapting isifociya into a belt raises the spectre of appropriation—can an unmarried woman wear my interpretation of isifociya without upsetting Zulu traditionalists? As a designer, I do not aim to constrict the body like isifociya by holding in the stomach, or attaching the traditional ritualistic connotations to it. Rather, I endeavour to alter the function of the object so it may be utilised as a fashionable accessory. Therefore, I am borrowing an aspect of isifociya from my culture in order to create a product that is re-imagined within a post-colonial context, owing to the fact that cultural identity is not static but moves with the times.

For this research, incorporating jewellery techniques that produce Eurocentric stylisation with indigenous items transforms isifociya into a contemporary object. In the history of Zulu beadwork, fusing different cultural and historic references in order to create hybrid identities would not be a novel concept. Nettleton (2014:100-101) argues that although beadwork did more than rigidify lines of division between people, it also combined tradition and modernity in a hybrid way. This was possible because Africans were able to merge aspects of indigenous and Western cultures in order to develop a hybrid body. Indigenous peoples utilised the beaded body as a form of resistance that signified and asserted their tradition and their modernity.

This research set out to use historical material retrieved from archives in order to investigate whether Zulu adornments can be reinvented in a post-colonial context. Through analysing the data and findings, the objective of the research was achieved, by way of the participants who agreed to take part in the surveys. The findings presented evidence that participants of diverse cultural affiliations, including Zulu women living in both urban and rural areas, were receptive to the isifociya as a reinvented Zulu adornment.

Form did not dictate function; what changed in the reimagined version of isifociya was its materials, but the function remained the same. I established that for indigenous Zulu women who still hold to traditional principles, this isifociya could still be used for its original function, despite my designs being different from those of the traditional object. From a cultural perspective, the grass still holds great significance, and the embellishments do not take away from its value. However, participants from diverse cultural backgrounds considered it another contemporary piece designed with an African aesthetic.

Another objective of this study was to create contemporary jewellery with a Zulu aesthetic in order to locate it as an Afrocentric form. I designed contemporary art jewellery pieces with a Zulu aesthetic, and participants from urban areas still identified the object as belonging to an indigenous culture, although interestingly they could not locate the item with any specific ethnic group. This study afforded me the opportunity to further my knowledge of a practice that exists within my culture. But most importantly, it allowed me to create work that is recognisable of a Zulu identity.

By the end of the making process, I came to realise that jewellery is not only an intimate object, but it also encompasses the viewer’s interpretations and the meanings they attach to it. The materials I used were not necessarily precious or valuable, as with most contemporary jewellery pieces. Rather, the value of isifociya is linked to its transformation from a ritualistic adornment into a utilitarian and fashionable object.

Since jewellery acts as an extension of an individual and expresses his/her character and affiliation to a specific group within society, it acts as a means of communication by raising or addressing questions. This study unravelled the complexities associated with identity by making apparent the ways in which our surroundings influence who we are, and how we navigate the world. Whether or not we choose to recognise the experiences that have shaped us, we have a natural inclination to view the world through a lens influenced by our experiences. The research highlights the fact that culture and its traditions are forever evolving, and will always adapt to the demands of the era in which it finds itself. Adapting and evolving does not necessarily equate to the loss of identities, because identity itself is not fixed, but constructed and linked to cultural adaptations.

Author

Khanya Mthethwa is an award-winning jewellery designer that was born in Kwa- Zulu Natal, currently working as an academic at the University of Johannesburg. Some of her prominent accomplishments within academia, include a Masters of Art in the field of design, Rough Diamond Evaluation and Diamond cutting certificates. When she is not immersed in her studies and lecturing, she takes on the role of an editor, founder and CEO of Changing Facets magazine – an online magazine that helps designers gain exposure and garner the attention of potential clients. Her advocacy and passion for the growth of jewellery in the country, has since become the driving force behind her recently starting the South African Jewellery week event which is notably the first platform of its kind in the country.

Khanya Mthethwa is an award-winning jewellery designer that was born in Kwa- Zulu Natal, currently working as an academic at the University of Johannesburg. Some of her prominent accomplishments within academia, include a Masters of Art in the field of design, Rough Diamond Evaluation and Diamond cutting certificates. When she is not immersed in her studies and lecturing, she takes on the role of an editor, founder and CEO of Changing Facets magazine – an online magazine that helps designers gain exposure and garner the attention of potential clients. Her advocacy and passion for the growth of jewellery in the country, has since become the driving force behind her recently starting the South African Jewellery week event which is notably the first platform of its kind in the country.

Comments

I am taken with Khanya’s project to engage with Liesbeth Ten Besten and the other eurocentric writers. There are things Khanya says which only a person of indigenous South African origin can say with authority. Her interest in hybridity is a way to engage with Europe / the West. As a perons who grew up ‘white’ in apartheid, I have tried this too.

There is more to say about the post colonial movement and South Africa. Her essay ends too happily. We/ they are still un-/ under-represented on the international spectrum of adornment practice. No-one of the younger jewellers is addressing the importance of Mapungubwe.

Muhle umsebenzi. Nyambose!

Ngaze ngaziqhenya ngomsebenzi owenzile, dadewethu..ngisigqokile kwamanje isifociya..kwesami isigodi sikholelwa ekutheni siyavikela siphinde siqinise umuntu wesfazane.

Thank for that comment Nomkhosi Khanyile. That’s wonderful to hear.