Look to the Rose that blows about us—

“Lo, Laughing,” she says, “into the World I blow:

At once the silken Tassel of my Purse Tear,

and its Treasure on the Garden throw”

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Persian arts are particularly known for their embellishment. Designs in carpets, ceramics, glass and wood inlay feature ornate arabesque patterns that celebrate beauty in nature. In the West, modernism aimed to remove the decorative in order to reveal the thing itself. In 1908, Adolf Loos famously equated ornament with crime, involving unnecessary labour which is bounded to be quickly dated. Postmodernism welcomed it back, but as pastiche, mixed up with everything else. In a digital age, embellishment seems crowded out by a flickering array of images. Yet the act of decorating seems an important response to our world, particularly giving expression to place.

One promise of the Persian Prospect is a re-valuing of ornament. As with Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat in 1859, Western writers have looked to Persian poetry as a way of appreciating the evanescence of life. This is a broader vision that is otherwise missing from pragmatic Anglo mindset. Yet it is a paradox of Persian culture that this appreciation of finitude is combined with the intense production of works that have lasting beauty. Maybe acknowledging the vanity of human endeavour grants license to create art beyond the normal calculus of daily business. This can be an important idea for other countries beyond Iran where that calculus encroaches increasingly more into our garden.

Dr Omid Shiva offers the following analysis of embellishment in Persian culture:

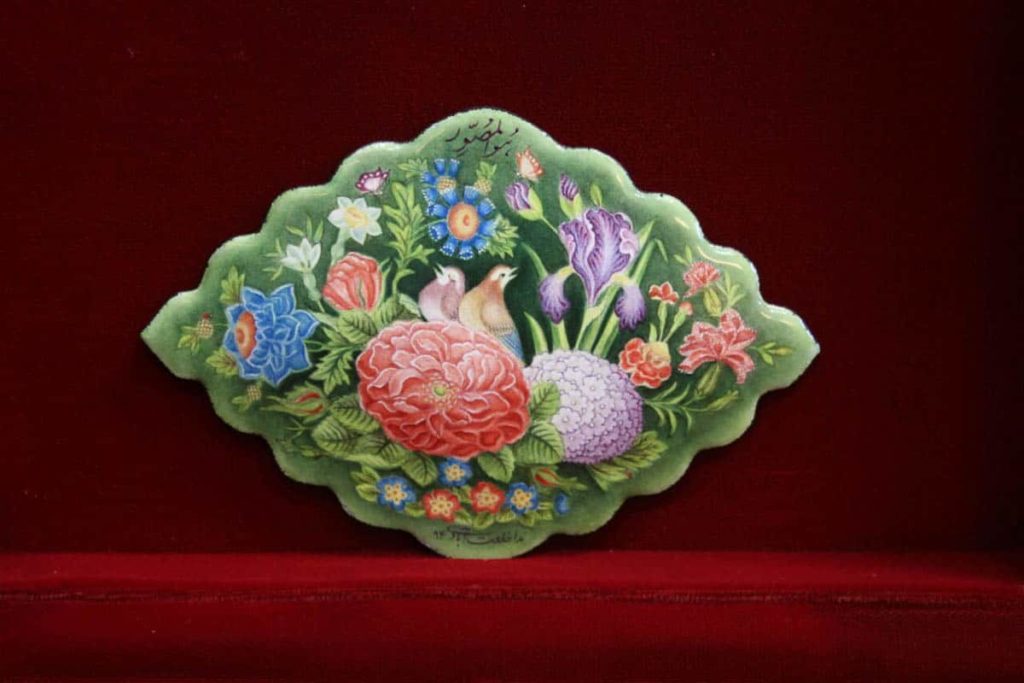

Gol-o-Morgh is a style in Iranian miniature. It is a symbol of God;s blessing—a fine and graceful manifestation of the creator. The romantic dialogue between flower (gol) and bird (morgh) can be described as a symbol of God praying. Flower (gol) is in the place of beloved and the bird (morgh) is the lover. The creation of harmony between the elements of drawing is very elegant in Gol-o-Morgh miniature. It is not necessary to draw the bird, but in the event of presence, it is waiting patiently to blooming the flower and making love with it. Sometimes the bird separates itself from the material world by heights and euphoria state and it has ascending state to the spiritual world. Historically, the composition of the plants and the birds began from the time of drawing geometric designs to plants. The flowers and the plants with the ring of tissues and full of the maze can accept geometric designs, but the birds need to non-geometric designs because of the softness of their organs. The works of the Gol-o-Morgh are from the Seljuk, Safavi and Qajar era which differs from each other but the trend of their changes has been slow during the time. In the late Safavid dynasty era, the birds were carefully painted. But then a dramatic change can not be seen in this art. There are differences in the way we perform, for example the petals are full in Shiraz style but in another the styles are thin and small.

The following artists are working in Iran, originally from Iran or for whom the decorative is an important part of their work. Some share images of the unadorned material that preceded decoration, so we can appreciate its effect.

Seyyed Reza Safavi | Zahra Tondkar | Baharak Omidfar | Bahram Taherian | Neda Khalatabadi | Shabanali Ghorbani | Narges Amirniroomand | Afsaneh Modiramani | Leila Farseneh | Khosrow Ashegi | Afsaneh Ahmadian | Hoda Afshar | Maral Mamaghanizadeh | Mehrzad Mumtahan | Ailin Abrishami | Maya Weaves | Stephen Bowers | Fiona Hiscock | Jordana Angus | Bic Tieu | Nalda Searles | David Pottinger | Holly Grace | Naoko Inuzuki | Kylie Stillman

Seyyed Reza Safavi

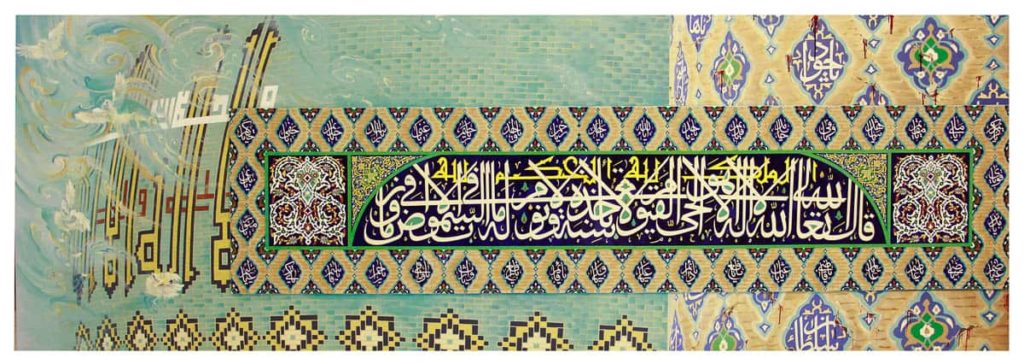

- Seyyed Reza Safavi, Goharshad, 2016, matching different material and colors, including Schmincke Aero ink, acrylic. etc., 1 × 3 m, photo: Zahra Tondkar

- Seyyed Reza Safavi, Goharshad, preparation

- Seyyed Reza Safavi, Goharshad, preparation

- Seyyed Reza Safavi, Goharshad, preparation

- Seyyed Reza Safavi, Goharshad, preparation

- Seyyed Reza Safavi, Goharshad, preparation

Mashhad, Iran.

Motifs and inscription derived from the tiling of Mosque Goharshad in the Shrine of Imam Reza which is dated back to the Timurid period. In this work, we tried to show the incident of shooting people at the precinct of Goharshad by Reza Shah Pahlavi’s command. Broken tiles in the background and flowing of blood between them indicate the incident and the depth of this tragedy. This work is maintained in Museum of Mashhad Municipality.

Zahra Tondkar

- Zahra Tondkar, tear, preparation

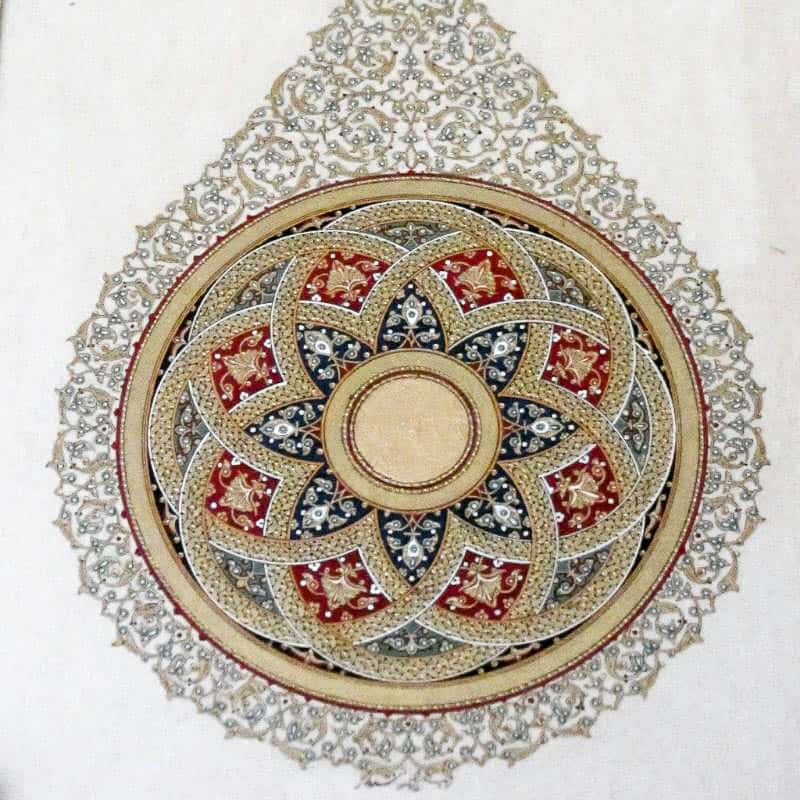

- Zahra Tondkar, tear, 2016, gouache, watercolor, 24 carat gold powder, 24 carat gold plate, 34 × 20, Photographer: Zahra Tondkar

- Zahra Tondkar, tear, 2016, gouache, watercolor, 24 carat gold powder, 24 carat gold plate, 34 × 20, Photographer: Zahra Tondkar

Mashhad, Iran

Reason of creating this work: reviving Iranian arabesques motifs in Timurid period which has been used in architecture and embellishment of that time. These motifs nowadays changed to the form of tear or the cypress which represent freedom and immortality. Procedure: 1. Sketching; 2. Making canvas or suitable field for performing the work; 3. Pencil drawing on the canvas; 4. Coloring and performing different techniques; 5. Retouching and embellishing; 6. Using different fixative material to protect the work

Seyyed Reza Safavi and Zahra Tondkar

- Heart and World: Seyyed Reza Safavi and Zahra Tondkar, heart and world, 2015, 50 × 70 cm, photo: Zahra Tondka

- Heart and World: Seyyed Reza Safavi and Zahra Tondkar, heart and world, 2015, 50 × 70 cm, photo: Zahra Tondka

Technique: ink, gouache, watercolor, using several old embroidered parts dating back to 200 years ago in the context and margin of work. Text: “Apart the heart which is dear and valuable to be protected, the world and everything in it should be left behind.” Saeb Tabrizi

The story behind it: creating a work that shows and expresses theological and mystic concepts, which are exist in Iranian culture, by matching the art of calligraphy (a well-known poem of Saeb Tabrizi) with the art of Tasheer.

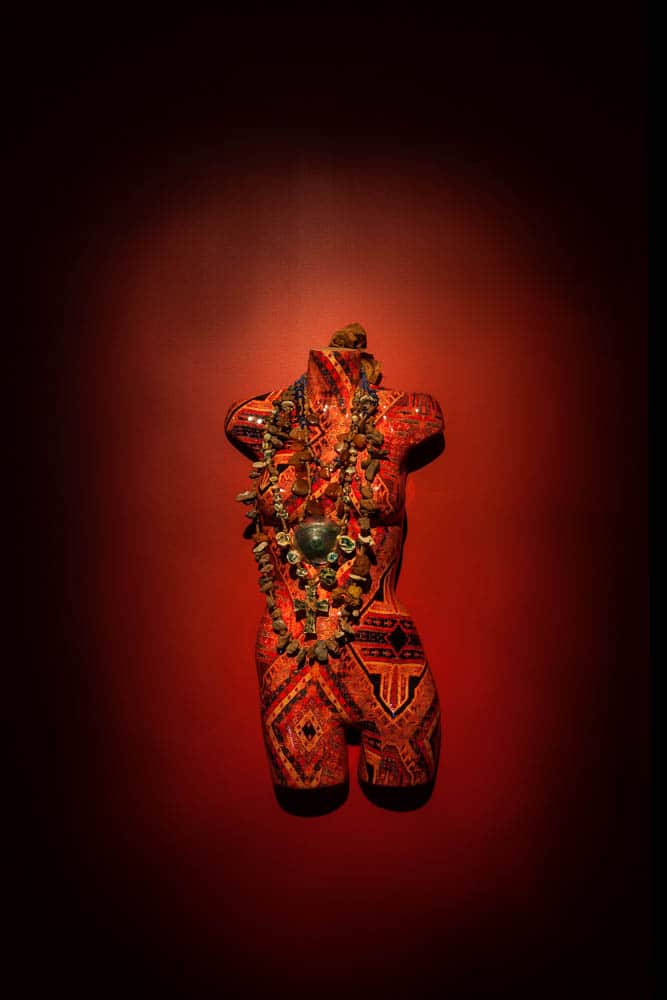

Baharak Omidfar

- Baharak Omidfar, Sepandarmazgan (The Celebration of the Earth), From collection of In Praise of the Nature, 2016, brass, copper, glass, different Gems ,photo: Mohammad Sorkhabi

- Baharak Omidfar

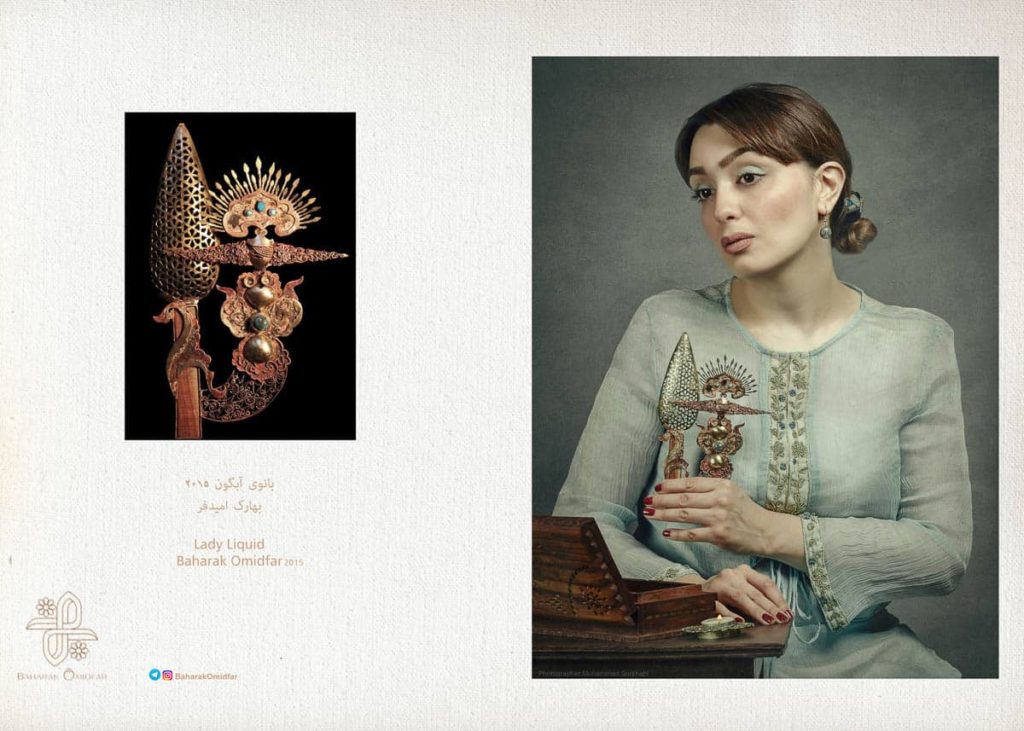

- Baharak Omidfar, Lady liquid

Mashhad, Iran

This jewel refers to Sepandarmaz, the goddess of the Earth who is protector and advocate of the earth in the Ancient Persia.Sepandarmazgan is the name of the celebration for the earth that be held for commemoration of the earth and the woman in ancient Persia. This jewel is the symbol of old dream for establishment of everlasting peace between man and man, and man and nature on the earth. The goddess of the earth is the occult symbol of this kind of wish.

Bahram Taherian

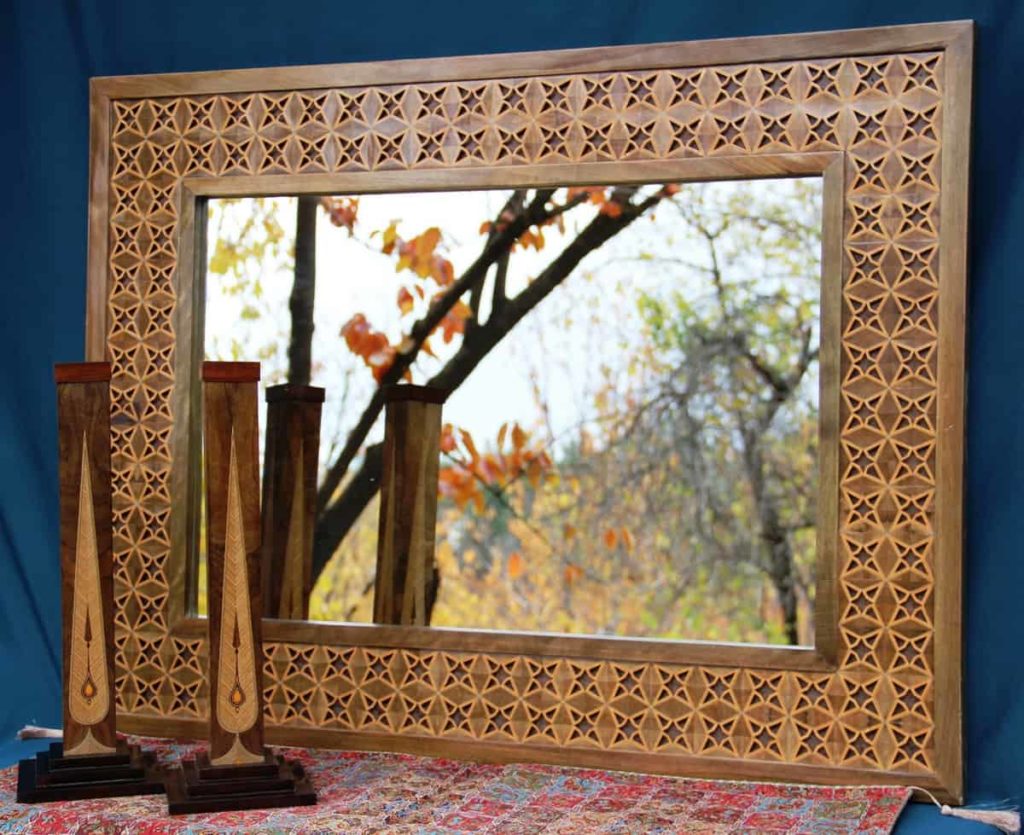

- Bahram Taherian, cancellate star design used in the mirror frame of pictures 1 and 2

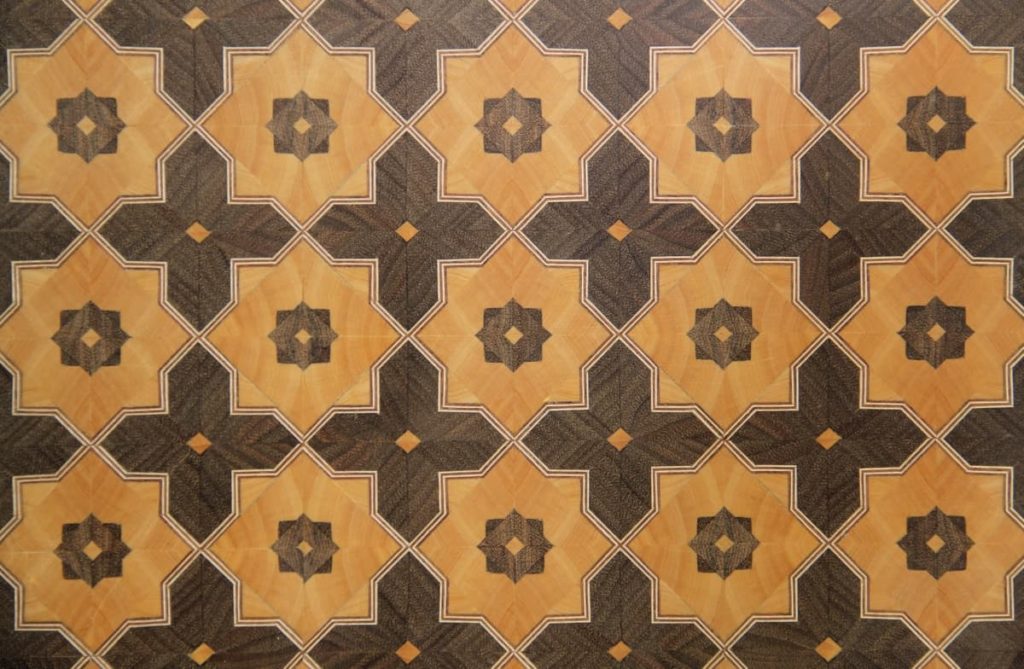

- Bahram Taherian, Dining table side designs with mehr kari technique, 2015-2016, walnut, maple, cashew, buck thorn wood, brass plates gelatin glue , white carpenters glue and polyvinyl acetate, 125 cm x 245 cm

- Bahram Taherian, new design using mehr kari technique, cashew , maple, walnut wood and brass plate and gelatin glue

- Bahram Taherian, Mehr Kari round table, 2012, walnut, cashew, buck thorn wood , boxwood , ebony wood white carpenter’s glue, gelatin glue and polyvinyl acetate, 120cm diameter

- Bahram Taherian, Mehr Kari round table, 2012, walnut, cashew, buck thorn wood , boxwood , ebony wood white carpenter’s glue, gelatin glue and polyvinyl acetate, 120cm diameter

- Bahram Taherian, shams and Chalipa figure, 2014, boxwood, walnut and maple Chalipa is among the famous forms in Iran, mostly used in architecture,

- Bahram Taherian, wooden candlestick with the Persian Cypress figure, 2014, boxwood, maple, cashew and walnut and gelatin glue The Persian Cypress is taken from the figures of Persepolis which has a special place in Persian culture.

- Bahram Taherian, Cancellate mirror frame and musical instruments in the picture contains brass plates and gelatin glue, 2014, walnut, boxwood, maple and cashew

- Bahram Taherian, Cancellate mirror frame and musical instruments in the picture contains brass plates and gelatin glue, 2014, walnut, boxwood, maple and cashew

Made in Tehran

Neda Khalatabadi

- Neda Khalatabadi, painting enamel on copper, 11 x 8 cm

- Neda Khalatabadi, painting enamel on copper, engraved copper frame, size with frame, 9.2 x 6.7 cm

- Neda Khalatabadi, silver necklace and earrings, 2016, cloisonne enamel on copper

Shabanali Ghorbani

- Shabanali Ghorbani, Protect nature, 2016, ceramics, 32 x 18 cm, photo: Shabanali Ghorbani

- Shabanali Ghorbani, Iran, 2008, ceramics, 4 x 1.8 m, photo: Shabanali Ghorbani (This work is inspired from different historical building from different regiona of Iran and also motives and designs from historical and Islamic periods of Iran.)

- Shabanali Ghorbani, Bull, 2016, ceramics, 45 x 24 cm, photo: Shabanali Ghorbani (This work is inspired by historical bull designs from 1000 BC from Marlik and Talesh region in north of Iran.)

- Shabanali Ghorbani, Protect nature, 2016, ceramics, 35 x 19 cm, photo: Shabanali Ghorbani

- Shabanali Ghorbani, Protect nature 1, 2016, Ceramics, 22 x 18 cm, photo: Shabanali Ghorbani

- Shabanali Ghorbani, Desert Flower, 2016, ceramics, 35 x 25 mm, photo: Shabanali Ghorbani (This work is inspired of flowers in deserts of Iran and a persian historical splash colourful glaze is applied on it)

Made in Tehran and New York.

Narges Amirniroomand

- Narges Amirniroomand, Water Lili, 2015, 18k Gold, pearl, leather, photo: Mehry Shirboty

- Narges Amirniroomand, Water Lili, 2015, 18k Gold, pearl, leather, Photo: Mehry Shirboty

Made in Iran,

All my designs are inspired by nature and in this collection I was inspired by Water Lili flower. To contribute to the idea of sustainability, which is my main area of concerns, I tried to combine other materials in one design and I applied the DfD strategy which is called design for disassembly.

Afsaneh Modiramani

- Afsaneh Modiramani, tableau, silk, cotton, silver, 14 x 73cm

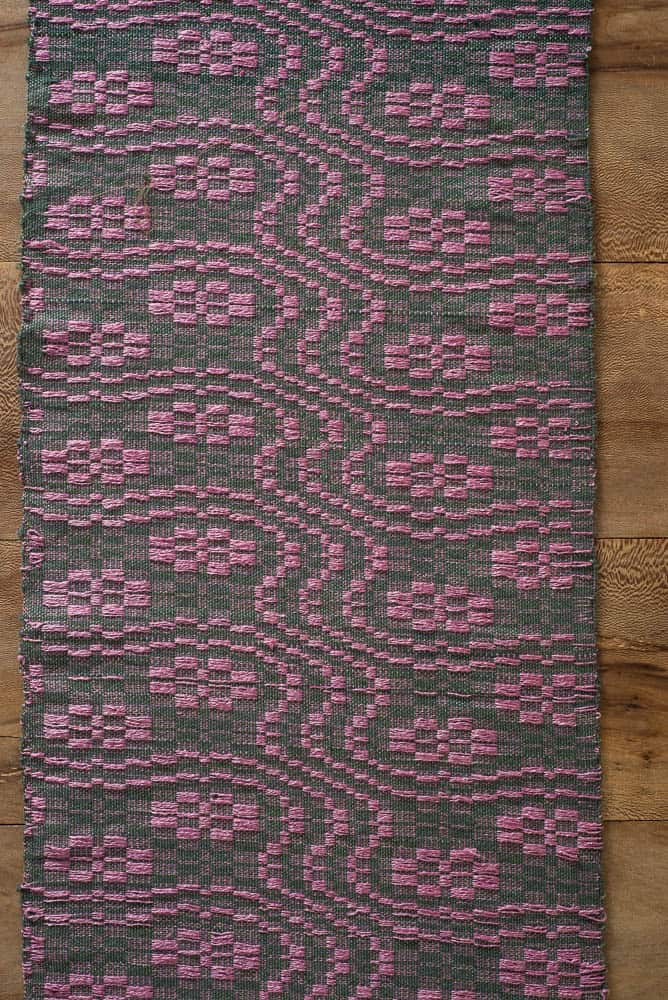

- Afsaneh Modiramani, runner, 58 x 166cm, silk, cotton

- Afsaneh Modiramani, shawl, 39 x 152cm

Leila Farseneh

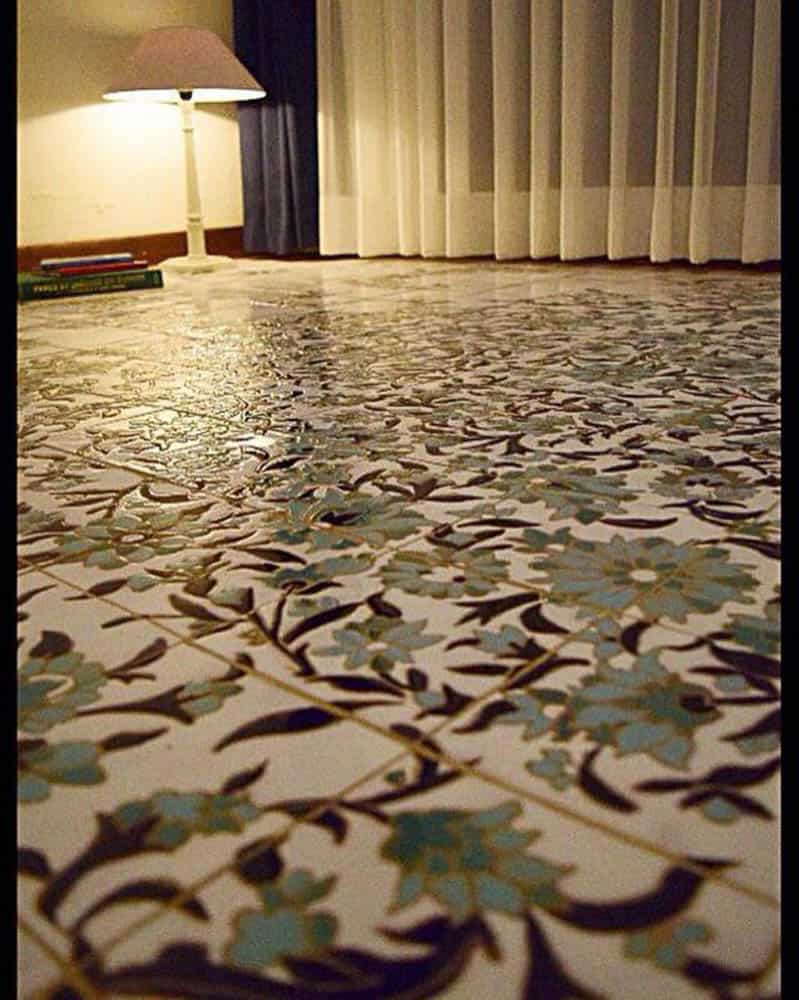

- Leila Farseneh, colorful table, 2015, clay and glaze, 4 x 1 metre (Injecting joy and happiness as we assemble together at the table)

- Leila Farseneh, Golemorg,2011, clay and glaze, 1 x 1 metre (These patterns originate from traditional beliefs of Iranians.)

- Leila Farseneh, peace, 2014, clay and glaze, 8 x 5 metres (The idea of this work is reaching peace and quiet life)

Made in Tehran, Iran.

Khosrow Ashegi

- Khosrow Ashegi, filigree flower pot, 2002, silver, 51 x 26cm

- Khosrow Ashegi

Made in Tabriz, Iran.

Hoda Afshar

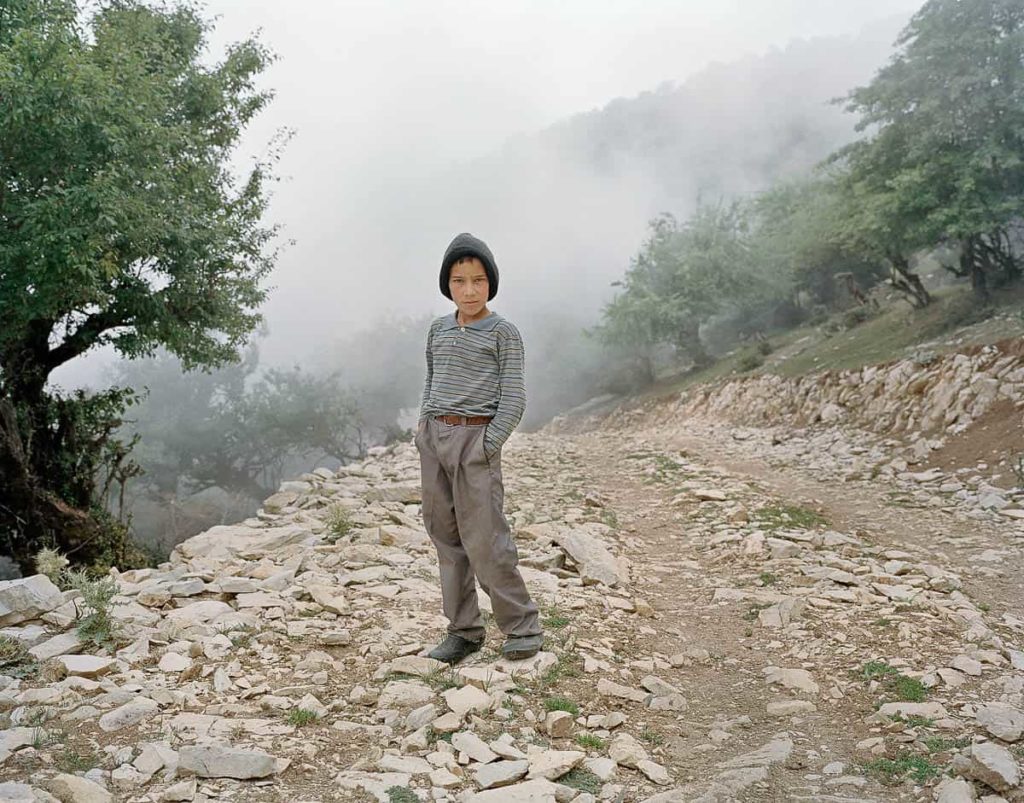

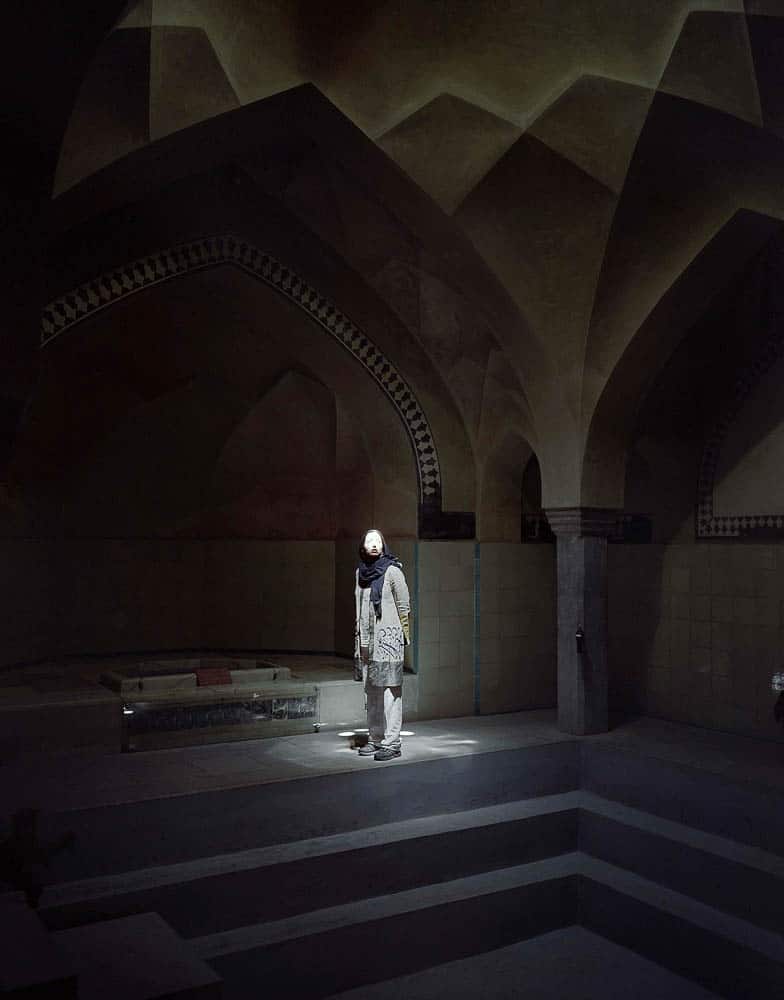

- Hoda Afshar, Exodus, I love you more, 2014, photographic series

- Hoda Afshar, Exodus, I love you more, 2014, photographic series

- Hoda Afshar, Exodus, I love you more, 2014, photographic series

- Hoda Afshar, Exodus, I love you more, 2014, photographic series

Photographed in Iran. Artist lives in Melbourne.

In the Exodus, I love you more is an ongoing photographic series about Iran that I began in 2014, eight years after my migration. The work explores my changing relationship to my country of birth, searching questions about memory and identity, and captures the changing faces of Iran during a time of great transition. It is a record of my evolving vision of my homeland—a vision that has been shaped by the feeling of distance that accompanies migration—and a documentary exploration of the play of history and presence in a place that’s often either misrepresented, or simply misunderstood, whether because of ignorance, or because of the difficulty in navigating the surface in a place where the surface and depth often exchange looks.

This work is about Iran, my Iran, and my relationship to Iran: a relationship that has been shaped by my having been away; by that distance that increases the nearness of all the things to which the memory clings, and which renders the familiar… strange, and distant. It is an attempt to embrace that distance and to turn it into a kind of seeing. To let what is both there and not there shine through the surface. To let the surface speak. It is an attempt to explore the interplay of presence and absence, and to discover the truth that lies there, in-between.

Maral Mamaghanizadeh

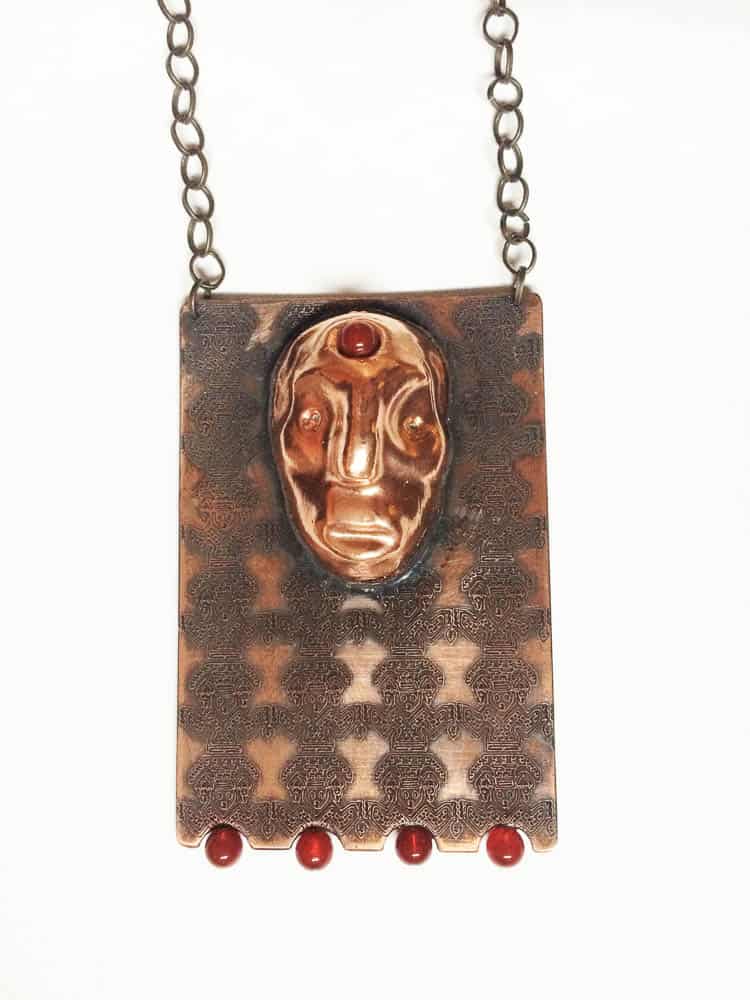

- Maral Mamaghanizadeh, Freshness Primitive,2016,Brass, beads, 10 x 6cm,photo: Maral Mamaghanizadeh

- Maral Mamaghanizadeh, Freshness Primitive,2016,Brass, beads, 10 x 6cm,photo: Maral Mamaghanizadeh

Birmingham, UK

This pendant made from copper electroforming and engraving. I was tried to renew and mix the primitives shapes which used in carpets and mask and sculpture.

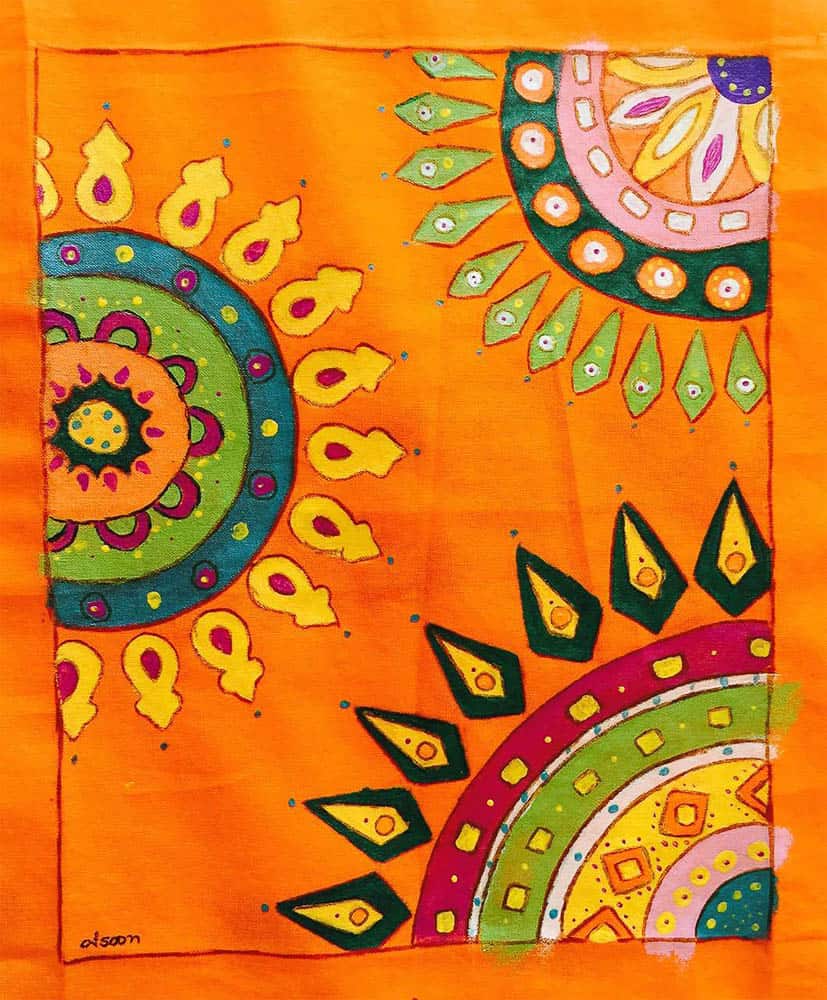

Afsaneh Ahmadian

- Afsaneh Ahmadian, Spring garden, fabric and fabric paint, 24 x 22cm, photo: Afsaneh Ahmadian Vibrant colours and colourful flowers which reminds me of my spring in Iran.

- Afsaneh Ahmadian, Bote Jeghe, 2016, fabric and fabric paint, 24 x 22cm, photo: Afsaneh Ahmadian. One of the unique and traditional Persian designs known as Bote Jeghe, combined with modern colours.

- Afsaneh Ahmadian, before decoration

- Afsaneh Ahmadian, Desert, 2016, fabric and fabric paint, 24 x 22cm, photo: Afsaneh Ahmadian. Inspired by Persian Gelim patterns. Gelims are flat tapestry-woven carpets or rugs. the Persian gelīm (گلیم) means ‘to spread roughly’.

- Afsaneh Ahmadian, Summer sun, 2016, fabric and fabric paint, 24 x 22cm, photo: Afsaneh Ahmadian. The orange colour represents the summer heat and you can feel the sun’s warmth through observing this piece.

Made in Melbourne.

http://artistsforasylumseekers.org

Mehrzad Mumtahan

- Mehrzad Mumtahan, Untitled (Healing Series – Vessel), 1993, Earthenware White Clay and Raku Glaze (H 330mm X W 350mm X D 250mm) photo: Mehrzad Mumtahan

- Mehrzad Mumtahan, Untitled (Healing Series – Vessel), 1993, Earthenware White Clay and Raku Glaze (H 250mm X D 150mm) photo: Mehrzad Mumtahan

- Mehrzad Mumtahan, Untitled (Healing Series – Vase), 1993, Earthenware White Clay and Raku Glaze (H 250mm X W 170mm X D 160mm) photo: Mehrzad Mumtahan

Buffalo New York, USA.

A series of work that I did while studying in the US in 1993, using earthenware (low fired and porous clay) and a Japanese glazing technique called Raku. At that time I was very alarmed (and still am) by seeing the level of pollution that was being produced, and the subsequent damage caused to the environment. In these series I was exploring concepts related to saving the planet and working with themes such as healing, mending, fixing and recycling. The pieces were also made from recycled clay and sand, for Raku firing I used maple tree leaves collected from the ground and not saw dust which was commonly used. This technique involves a process in which work is removed from the kiln at bright red heat and subjected to post-firing reduction (or smoking) by being placed in containers of combustible materials (dry leaves in this case), which causes crazing in the glaze surface.

Ailin Abrishami

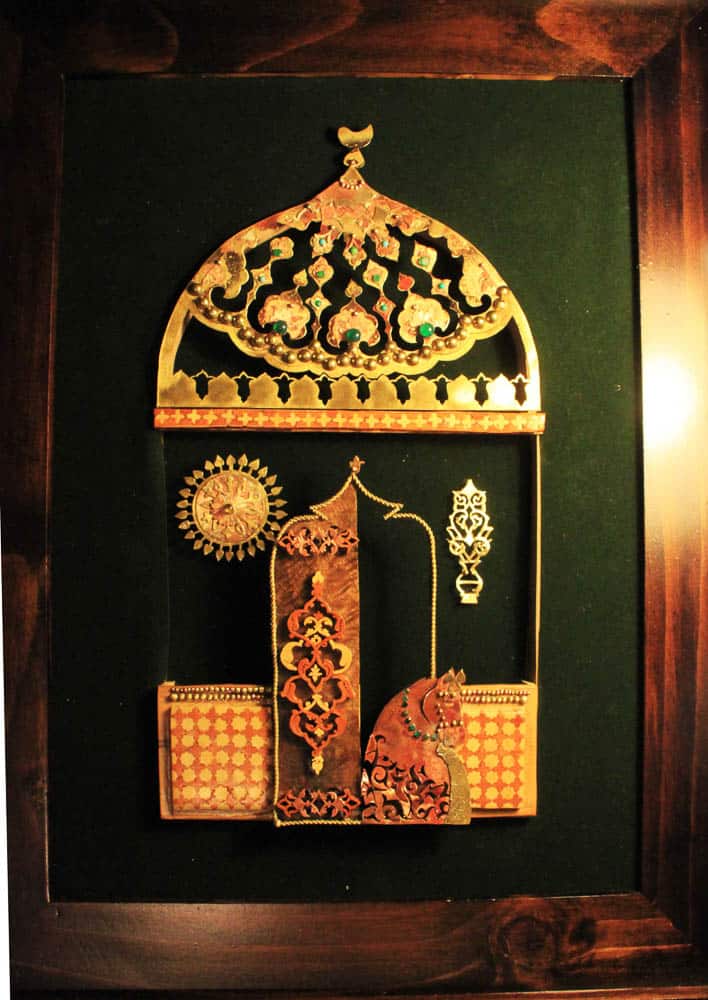

- Ailin Abrishami, Integrated jewelry and wood panels “shahnameh baysonghori”, 2015, brass and stone and wood, 40 x 50cm

- Ailin Abrishami, Integrated jewelry and wood panels “shahnameh baysonghori”, 2015, brass and stone and wood, 40 x 50cm

Mashhad, Iran

Decorative frames combining art and jewelry inspired by the paintings of Shahnameh Bāysonḡorī.

http://instagram.com/ailin_jewelry

Maya weaves

- M. Sikdar, Kantha embroidery, 2013, Tussar silk, 70″X 100″,

- M. Sikdar, Kantha embroidery, 2013, Tussar silk,70″X 100″

Made in Narendrapur, West Bengal, India.

Maya weaves is a cluster of 300 plus women artisans . Founded by a President award winner and her daughter, it specialises in hand embroidery and hand weaves in cotton, Khadi, linen, silk,Tussar and Jamdani craft.Working since 1996, it is working with craft houses, govt emporiums, fashion designers,galleries, international buyers and fashion houses.

Stephen Bowers

- Stephen Bowers, ‘Camouflage’ series plate, 2016, high-fired earthenware, underglaze colour, clear glaze, on-glaze gold and enamel, 33 cms dia X 2 cms deep, work-in-progress photo courtesy of the artist

- Stephen Bowers, ‘Camouflage’ series plate, 2016, high-fired earthenware, underglaze colour, clear glaze, on-glaze gold and enamel, 33 cms dia X 2 cms deep, work-in-progress photo courtesy of the artist

- Stephen Bowers, ‘Camouflage’ series plate, 2016, high-fired earthenware, underglaze colour, clear glaze, on-glaze gold and enamel, 33 cms dia X 2 cms deep, work-in-progress photo courtesy of the artist

- Stephen Bowers, ‘Camouflage’ series plate, 2016, high-fired earthenware, underglaze colour, clear glaze, on-glaze gold and enamel, 33 cms dia X 2 cms deep, work-in-progress photo courtesy of the artist

Made In a shed in the back yard of my house, Adelaide, Australia.

My pottery emphasises underglaze brushwork decoration. I work in a small shed to build up layers of painted decoration on (mostly) white earthenware. I always include references to nature, especially Australian botany and zoology (often parrots and cockatoos) as well as references to craft tradition and history.

Fiona Hiscock

- Fiona Hiscock, Banksia Serata Vessel and Water Pitcher, 2015, Stoneware clay with porcelain slip, 50 x 23 x 23, photo Chris Sanders, 2. Banskia Serrata vessel with handles, 2015, Stoneware clay with porcelain slip, 46 x 23 x 23, photo Chris Sanders, 3. Two Banksia Serrata Jars, 2015, Stoneware clay with porcelain slip, 31 x 16 x 16 cm, photo Chris Sanders

- Fiona Hiscock, Banksia Serata Vessel and Water Pitcher, 2015, Stoneware clay with porcelain slip, 50 x 23 x 23, photo Chris Sanders, 2. Banskia Serrata vessel with handles, 2015, Stoneware clay with porcelain slip, 46 x 23 x 23, photo Chris Sanders, 3. Two Banksia Serrata Jars, 2015, Stoneware clay with porcelain slip, 31 x 16 x 16 cm, photo Chris Sanders

Made in Melbourne, Australia.

These vessels are coil built and covered with a porcelain slip that is used as a surface for painting. The imagery is focused on Australian native species, and is derived from close observation and drawings on site.

Jordana Angus

- Jordana Angus, galin-dyi-yiray (island sun), 2016, aluminium, ink, acrylic paint, cats eye operculum ice resin, 7cm diameter, photo: Jordana Angus

- Jordana Angus, gadhang-yadhaa (Ocean dream), 2016 aluminium, ink, acrylic paint, , ice resin, 7cm diameter, photo: Jordana Angus

Made in Brisbane, Australia.

*Please note that titles of work are in my traditional Wiradjuri language with the English translation in Brackets

These pendants are from my current series of work which portray abstract landscape and seascape views of Australia to affirm my connection to place as an Aboriginal woman; and to make others aware of the beauty I find in nature. The aluminium pieces have been embellished with ink, acrylic paint and have a cats eye operculum (passed down by my maternal grandmother) set into the piece with resin to add value to a metal that is often overlooked or discarded.

http://jordi1483.wixsite.com/artbyjordana

Bic Tieu

- Bic Tieu, Fitted circumferences, 2016, copper, lacquer, gold leaf, connected lid and base vessels, 33 diameter x 61 total height mm

- Bic Tieu, Joss Vessels, copper, lacquer and silver leaf, 2016, 32 diameter x 52mm and 32 diameter x 35mm

- Bic Tieu, Twang, 2016, vessel, copper, lacquer, shell, 38 x 24 x 33 mm

Bic Tieu’s work takes the traditional lacquer craft from its source in Japan and interprets it through her experience growing up as a south-east Asian in western Sydney. Made in Sydney. See here for catalogue essay.

Nalda Searles

- Nalda Searles, Puabi gift to Sigmund, 2013, beads (strand one, small lapis lazili holed stones; strand two, old African carnelian from Mali and a single roman glass bead from Afghanistan circa 900AD; strand three, ceramic beads made by Eileen Keys (dec) and glazed with crushed Australian minerals; strand four, stones with natural holes collected in desert riverbeds in Western Australia, photo: Bewley Shaylor

- Nalda Searles, Puabi gift to Sigmund, 2013, beads (strand one, small lapis lazili holed stones; strand two, old African carnelian from Mali and a single roman glass bead from Afghanistan circa 900AD; strand three, ceramic beads made by Eileen Keys (dec) and glazed with crushed Australian minerals; strand four, stones with natural holes collected in desert riverbeds in Western Australia, photo: Bewley Shaylor

Made in Perth, Australia

In developing artworks through the investigation into Sigmund Freud’s collection of antiquities it showed his inclination to Mesopotamian objects. Recently a tomb was discovered in that region. Within in it was the remains of a woman of high degree. She was wearing a neckpiece so elaborate that I thought how Freud would covet it. Having skills in putting various objects of embellishment into body adornment I made this neckpiece after Puabi towards Freud. It was part of an exhibition “An Internal Difficulty” PICA 2015 West Australia based on Freud’s collections.

David Pottinger

- David Pottinger, Nerikomi vessel, 2016, porcelain photographer Tim Gresham.

- David Pottinger, Nerikomi vessel, 2016, porcelain photographer Tim Gresham.

- David Pottinger, Nerikomi vessel, 2016, porcelain photographer Tim Gresham.

Made in Melbourne, Australia

My work employs the technique of nerikom. In doing so the vessels become a medium for sustained consideration, an opportunity to experience the work as a meditation beyond technique or form to true contemplation.

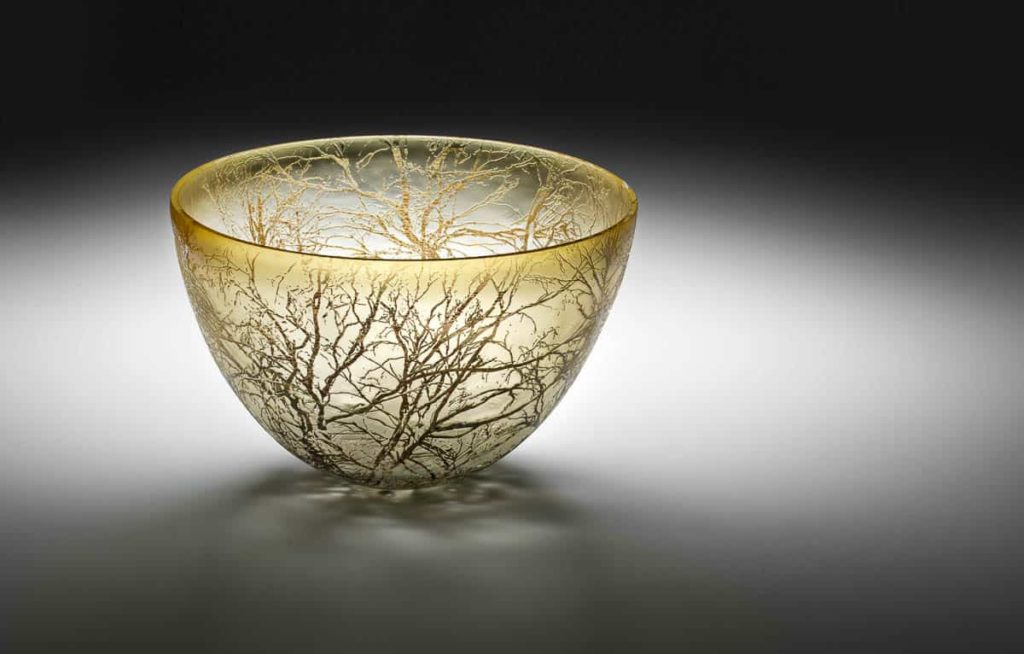

Holly Grace

- Holly Grace, Round mountain hut, glass

- Holly Grace, Devil’s hallow, glass

- Holly Grace, Horse camp hut

Made in Melbourne.

Glass is my lens to explore the complexity of the natural world. Exploring first with the camera and then with the material I use glass as a surface for translating light, creating landscapes both real and imagined, internal and external.

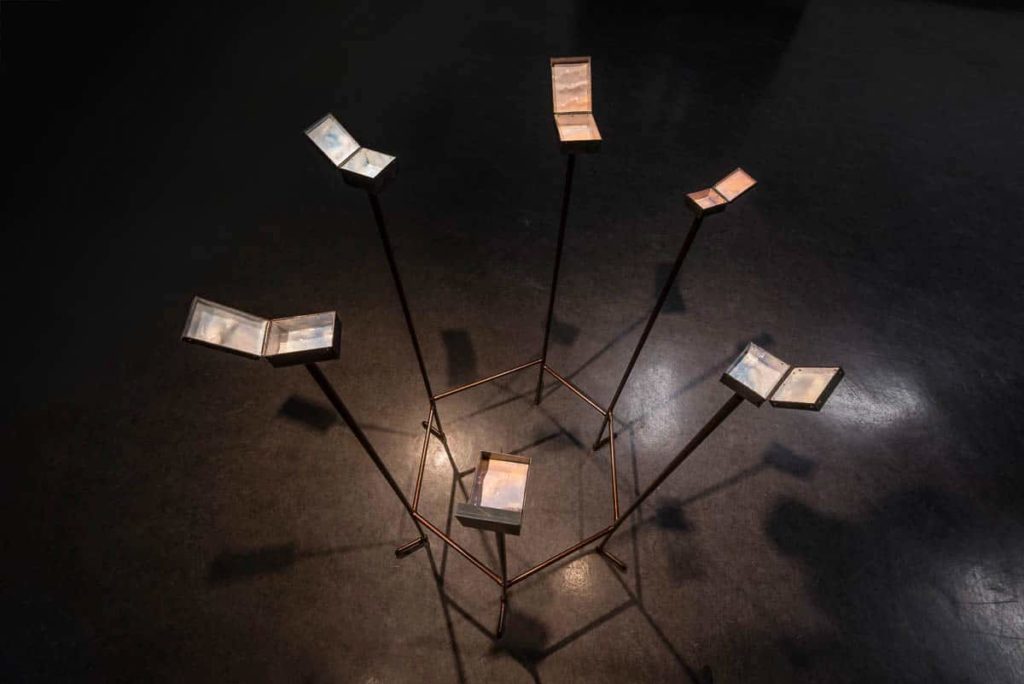

Naoko Inuzuka

- Naoko Inuzuka, Becoming Locals (objects and installation), 2016, mild steel, copper, enamel, Sterling silver, Copper pipe, 120 x 70 x 70 cm

- Naoko Inuzuka, Becoming Locals (objects and installation), 2016, mild steel, copper, enamel, Sterling silver, Copper pipe, 120 x 70 x 70 cm

Made in Melbourne.

Description of the work (written by Peter Westhood): Becoming Locals deliberates on the notion of ‘home’ and belonging, through ideas of diasporic communities over successive generations. Naoko’s work was formed as a result of a research trip to Hawaii in order to engage with the Japanese diaspora, but equally reflects on ideas of cosmopolitanism, the ideology that all of us essentially belong to a single community. Becoming Locals forms through ideas of re-location as a contemporary phenomenon, examining mobility and cultural hybridism. “Multiculturalism is an older 20th Century term. In visiting Hawaii with its indigenous people, immigrants historically from Asia and Portugal, and contemporaneously as part of the US, it seems clear that people in the Japanese diaspora aren’t concerned with the question of where they belong. Rather, I felt that there is more of a sense of ‘un-belonging’, where people have chosen to become ‘local’. (Naoko Inuzuka)”

Kylie Stillman

- Kylie Stillman, Bottle Drawings, 1999, plastic bottles and embroidery thread, 29.5 x 9 cm (diameter)

- Kylie Stillman, Bottle Drawings, 1999, plastic bottles and embroidery thread, 29.5 x 9 cm (diameter)

- Kylie Stillman, Bottle Drawings, 1999, plastic bottles and embroidery thread, 29.5 x 9 cm (diameter)

Made in Melbourne, Australia

Kylie Stillman’s inventive artworks draw from both modern art and craft traditions to transform ordinary materials into works of art. The artist says “it’s my own form of alchemy – taking something very common and then giving it nobility”.

Comments

“After witnessing the horrible massacre of the 1984 riots I realised painting a picture of the grotesque aspect of humanity was only making a beautiful object out of human misery. I wanted to give up all kinds of distorted protest images and look for something else in nature. I wanted to change my art from sloganeering to pure music. I turned my attention more and more toward Indian art and my work became more and more decorative. After all, the essential character of Indian art has always been decorative, ‘alankar’ as it is called. Decorativeness or ‘alankar’ is not a derogatory word for our art forms. The rhythmic patterns embellish our literature, music, art and architecture, making it unique and distinct from western culture. I started realising the importance of our unique art and culture.” ~ A. Ramachandran, excerpts from ‘A Visual Tapestry of Life’, an interview by Sudha G. Tilak in the upcoming Art Ichol Journal, 2016.