Yokings of the Felicity; Astha Butail (In collaboration with Raw Mango, M.Yasim); hand woven benarasi kimkhab textile (silk and gilded thread); weavers: Mustak Ahamad, Jagdish Prasad and Ramji Maurya; site specific dimensions; Gurgaon / Varanasi, 2013 – 2014

A painful strength, an invisible anti-sun, a forced source of energy, a shadow of spiritual light – the Black Sun appears in the oldest oral traditions of the world. It is mentioned in the Rig Veda along with Martand, the mortal egg. This symbolism of the twin, the conflict of the opposites, as also the unity of opposites, is deeply significant. Paralleled in ancient Greek wisdom, the analogy of the twin can be extended to any plane: like the Vedic twin sisters, Usha and Ratri (day and night); or the vertices of a particular frame or a set of co-ordinates changing from one to another: ‘cold things grow hot, a hot thing cold’, ‘a moist thing withers, a parched thing is wetted’.

Here, drawing upon Hiranya, the Cloth of Gold in Vedic literature, the artist uses Kimkhwab fabric, a traditional Varanasi silk brocade woven heavily with gold thread. This choice reflects her progress through an on-going dialogue with the Black Sun in recent years, her journey drawing upon her interactions with light, particularly in a 100 book project (each book consisting of seven pages), in which the last book was made with a gilded paper that reflected a movement to a higher plane of consciousness. A work that brings together elemental invocations of cloth, and cloth making, into a rigorous, sculptural work.

Martand, the eighth son of the goddess Aditi, was cast away. Her remaining sons manifest themselves in this installation as seven, cosmic structures. Each is a solar being, Aditya, a reference to the mutable minds of men desirous of being yoked to the Felicity, an eternal sunshine. Each is constructed in proportional ratios so that the first is 1/7th of the part of the last structure. Gold and grey, small and large, part and whole; the deep ochre features patterns of grey alluding to the grey areas that intersect and hamper the state of primordial-ultimate contentment. Unwoven gold threads represent the simplicity that underlies a composite form. The warps of bliss are tethered together to the roof, hinting at an inexpressible freedom.

Many of India’s ceremonial and ritual textiles feature the sun, in the form of a splendid rayed disk, as a timeless progenitor and benefactor. This traditional image returns in this panel, embroidered densely with multiple metallic elements. Its symbolic associations are discarded and replaced with a seemingly familiar reference to the nature of time: a complex, self-contained mechanism that never fully reveals itself. The workmanship here revives a distinctive characteristic of India’s historic metallic embroideries, which excelled in the massing of elements as closely as possible, to create continuous sheaths of metallic textures over fabric. The final effect is powerfully sculptural rather than decorative, the delicate, pliable purls and sequins coalescing into unyielding plaques of embossed and engraved metal.

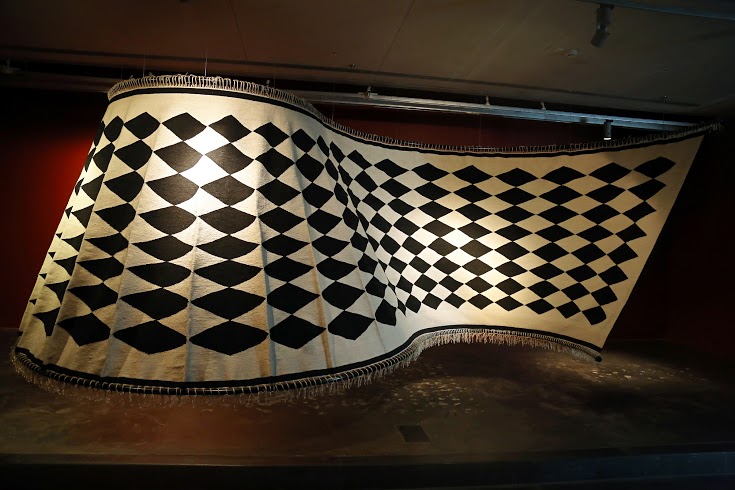

Flying Rug; Chandrashekhar Bheda (In collaboration with Mahender Singh); weaved and ribbed cotton; 120.0 x 420.0 inches (at) and 96.0 x 252.0 inches (displayed); New Delhi, 2014

Textile designer Chandrashekhar Bheda’s work has focused on breaking away from the square grid of the woven textile. Altering this fundamental principle, he creates a radical weave where warp and wefts no longer conform to traditional loom principles. From one end to the other, and from the bottom to the top, the character of the fabric keeps changing. Curvilinearity and weight vary continuously. A surface chequer-board of black and white diamonds, constantly advancing and receding in scale, heighten the illusion of spatial curvature and linear movement. The result is a highly dynamic object that defies gravity and perception, floating freely in space like the proverbial flying carpet. For this project, Bheda restructured the Panja Durrie loom by changing its fundamental geometry and technique. This work is the first in an upcoming series of large-scale textiles being woven by his team of weavers.

Yatra Kalamkari; Bérénice Ellena (In collaboration with Sri Niranjan, Institut Français); Kalamkari; 76.0 x 198.0 inches; Shrikalahasti, 2014

For its sheer power of narration, the Kalamkari of South India supersedes all other traditional Indian textiles. This Kalamkari draws its narrative form, unusually, from a pair of paisley motifs. Each is composed of a spiral stretching its tail, like a comet, to reach the other spiral, creating a dynamic movement between the two. The image suggests an outburst, a surge from one towards the other, the inter-penetration of two world-spirals. From the left to the right, one follows the journey, yatra, of designer, researcher, and screen writer Berenice Ellena, in an extended discovery of cultures.

From the right to the left, one recognises Draupadi’s endless sari from an episode in the Mahabharata. She finds Penelope, her Greek counterpart, on the far left, in a seamless evocation of historic characters, civilizations, and myths. Penelope unweaves at night the very fabric she weaves up in the day, just as Krishna weaves an endless sari to protect the faithful Draupadi. Inside one spiral, the fabled Greek labyrinth deceives the mind, and in another, Maya, the universal illusion, spreads her veil. Gandhi, Saraswati, Kabir, Pipa-ji, Namdev, and The Buddha, all appear as seers in this intensely personal narrative. The West and the East become parallel reflections in a philosophical reverie; and Ellena’s journey itself a metaphor for a shared, and equal, humanity.

SHE LL; Swati Kalsi; cotton and metallic thread on silk; dimensions variable; New Delhi / Bihar, 2014’ artisans: Anu Kumari , Rupa Kumari, Poonam Kumari, Komal Kumari, Kajal Kumari, Neha Kumari, Asmita Kumari, Amrita Kumari, Shalu Kumari, Sudhira Devi, Anita Devi, Juli Kumari

Sujani commonly refers to the traditional layering and sewing together of old, worn fragments of cloth for soft wraps, quilts and mats. In Bihar, the word sujani implies the coming together of ‘su’ (facilitating) and ‘jani’ (birth). It invokes the feminine deity, Chithariya Mata (Lady of the Tatters) who embodies an ancient philosophical idea: all discrete things belong to one whole, to which all things eventually will return. The sujani finds its most eloquent expression, therefore, in the gossamer wraps sewn for newborns, and for their conception in the kobarghar, the nuptial chamber. In this interpretation, textile designer Swati Kalsi explores a shell-like form that alludes feminine aspects of birth, nurture, and protection intrinsic to the traditional craft. Collaborating with rural women in a temporary urban workshop, Kalsi attempts to portray these women who guard and nurture an intimate world like a protective shell, all the while weathering formidable external forces.

Author

Mayank Mansingh Kaul is a Delhi-based textile and fashion designer. A design curator and writer, he is the Founder-Director of The Design Project India, a not-for-profit organization seeking to enable archival-curatorial-writing projects on Indian design.

Mayank Mansingh Kaul is a Delhi-based textile and fashion designer. A design curator and writer, he is the Founder-Director of The Design Project India, a not-for-profit organization seeking to enable archival-curatorial-writing projects on Indian design.