Clare Hooper re-creates an extended family in found heirlooms.

For me, the phrase “I remember” is a way of gaining an understanding of family and place. It invariably transpires with objects that were kept and treasured for that connection. Most people can relate to it. For me, it is about being part of a family that for the last three generations has experienced immigration and post-World War Two expatriation.

From my maternal and paternal grandparents to my siblings, we have lived (and died) in countries that weren’t where we were born. This has created adventurous lives as well as a disconnection from the friends and extended family left behind.

The inherited objects I have chosen to focus on are all relatively portable. We have a family saying, “home is where you unpack your suitcase”. They are also a reflection of my being a maker of jewellery and metal objects. They are small, intimate things and usually feminine. On considering my family history, my making and collecting, I have realised that they each feed and enrich the other. I can no longer say which came first or what is the most important to me. The objects themselves are not especially valuable in that they could not be easily exchanged for hard cash in times of need, but they would be hard to replace nonetheless. Maybe that is the power of the object, for me at least, that I couldn’t give it away.

- Artist unknown, Charm Bracelet, 925 silver, base metal, stones, circa 1960s

- Artist unknown, Hand Mirror, 925 silver, glass mirror, approx. 1918

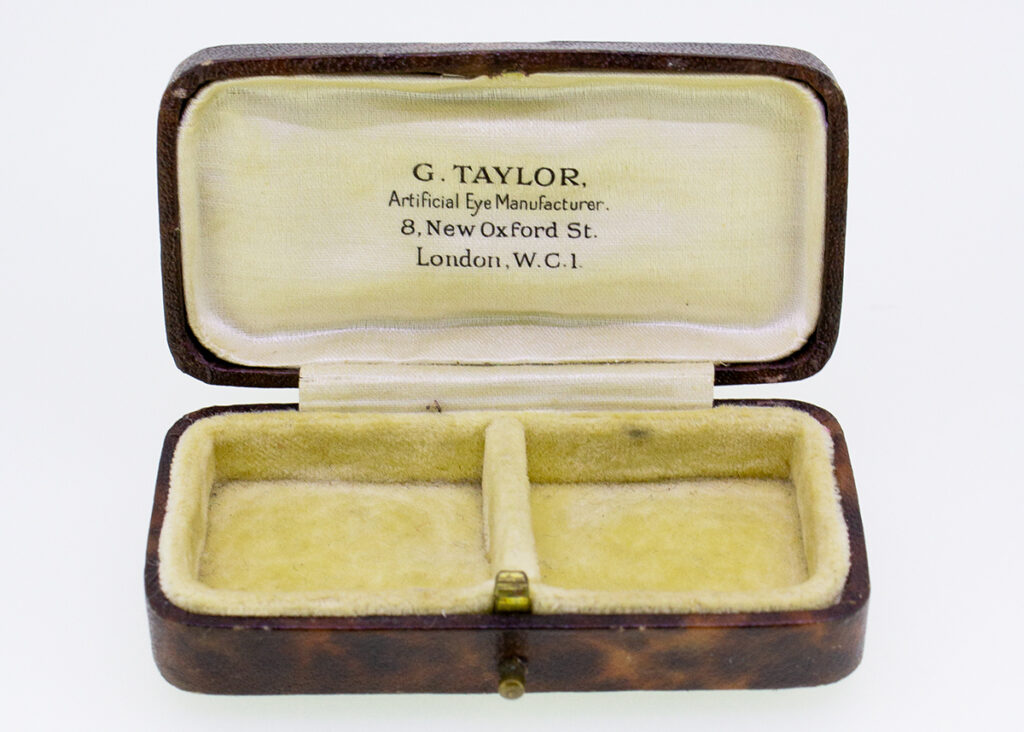

The items I have focused on are as follows: a silver charm bracelet with the lock dating from approximately 1962 from Birmingham, England with a variety of silver charms collected from places my maternal grandparents lived and visited in their time as ex-pats; a box that was for an artificial glass eye manufacturer based in London and connected to my maternal great-great-grandmother; and a base metal brooch shaped like a flower that belonged to my paternal grandmother. These specific items are functional today, but I also have items that need attention and alteration. They are a damaged silver hand mirror that dates from approximately 1918 made in Birmingham and belonged to my maternal great grandmother; a single 9-carat gold cufflink with the letter “A” engraved and also from Birmingham which belonged to my maternal great grandfather; a broken 9-carat gold rope chain necklace and some gold and stone earring in the process of being altered whose last owner was my maternal grandmother.

In focusing on this assorted collection there has been a realisation that because I didn’t experience an extended family upbringing, these objects have, in a strange way, become stand-ins for those people. The “I remember” stories linked to them are one of the few ways I can sense a belonging to something other than where I have grown up and lived. In our family, there isn’t a sense of regret in moving away from family and it has been strongly encouraged to keep looking forward and accepting choices made. But I find that acknowledging the loss of what may have been is still an important way of remembering those that are not with you. And this is what the objects have come to mean for me.

How these objects will then influence the work I am currently making is still a process I am working through. I don’t feel that they will be directly influential, such as making a modern version of a charm bracelet or feeling the need to melt down the bits of gold (though I haven’t completely discounted that option just yet). Perhaps it is due to their small and portable scale that this will be the direction I am heading towards and a preferred way of making for me.

Another way I am thinking of the work may be based on the idea of “New Heirlooms”, those objects and jewellery made to be the next generation of collectables for future members of my family, but like those that I have inherited aren’t made of so-called valuable materials. It harks back to what craft has always meant for me, the creation of objects that are made to satisfy the realms of aestheticism, practicality, skill, and the use of materials that reflect its best attributes.

Bibliography

Adamson, Glenn. Thinking through Craft. English ed. ed. Oxford: Berg, 2007.

Ahde-Deal, Petra, Heidi Paavilainen, and Ilpo Koskinen. “‘It’s from My Grandma.’ How Jewellery Becomes Singular.” The Design Journal 20, no. 1 (2017): 29-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1252564.

Bachelard, Gaston, and M. Jolas. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1994.

“The History of Charms and Charm Bracelets: A Short Introduction.” accessed 20 September, 2021, https://www.thecharmworks.com/HistoryofCharms.

Crosby, Alexandra, and Jesse Adams Stein. “Repair.” Environmental Humanities 12, no. 1 (2020): 179-85. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-8142275. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-8142275.

Jarrett, Christian. “The Psychology of Stuff and Things: Christian Jarrett on Our Lifelong Relationships with Objects.”. The Psychologist 26, no. no.8 (2013): 560-65. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-26/edition-8/psychology-stuff-and-things.

Koudounaris, Paul. Heavenly Bodies: Cult Treasures & Spectacular Saints from the Catacombs. Cult Treasures & Spectacular Saints from the Catacombs. London: Thames & Hudson, 2013.

Lindsay, Frances. Kippel/Kippel: Opus. Melbourne: Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Lipman, Caron. “Living with the Past at Home: The Afterlife of Inherited Domestic Objects.” Journal of material culture 24, no. 1 (2019): 83-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518801383.

Lovelace, Joyce. “What Lies Beneath: Jessica Calderwood’s Work Invites the Viewers to Dive Deeper.” American Craft Magazine, Feb/Mar 2019. Accessed May 25, 2021. https://www.craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/what-lies-beneath.

Manheim, Julia. Sustainable Jewellery. London: A. & C. Black, 2009.

Miller, Steven. Deaccessioning Today: Theory and Practice. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2018.

Olalquiaga, Celeste. The Artificial Kingdom. 1998 New York; 2002 Minneapolis: Pantheon Books; First University of Minnesota Press, first published 1998, this edition 2002.

Potts, Rolf. Souvenir. Object Lessons. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, 2018.

Ravenstein, Ernst Georg. Census of the British Isles, 1871 the Birthplaces of the People and the Laws of Migration. The Making of the Modern World. Part 2 (1851-1914). London: Trübner & Co., 1876.

Schliewe, Sanna. “Embodied Ethnography in Psychology: Learning Points from Expatriate Migration Research.” Culture & psychology 26, no. 4 (2020): 803-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X19898677.

Shelley, Fred. World’s Population: An Encyclopedia of Critical Issues, Crises, and Ever-Growing Countries. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2014.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narrative of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Baltimore; Durham: John Hopkins; Duke University Press, first published 1984; 2007.

Unger, Marian. Jewellery in Context. Europe: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2019.

Zembylas, Tasos. Artistic Practices: Social Interactions and Cultural Dynamics. Routledge/Esa Studies in European Societies. Hoboken, N.J: Taylor and Francis, 2014.

About Clare Hooper

I am currently studying for a Master of Fine Arts at Sydney College of Arts, USYD in the Jewellery and Object studio. In 2021, I held a show with fellow jeweller Jennifer Fahey at Stanley Street Gallery and I also will have work exhibited this year in the JMGA-NSW and Australian Design Centre show Profile. Visit www.clarehooperjewellery.com and follow @clarehooperjewellery

I am currently studying for a Master of Fine Arts at Sydney College of Arts, USYD in the Jewellery and Object studio. In 2021, I held a show with fellow jeweller Jennifer Fahey at Stanley Street Gallery and I also will have work exhibited this year in the JMGA-NSW and Australian Design Centre show Profile. Visit www.clarehooperjewellery.com and follow @clarehooperjewellery