I have never forgotten seeing my first suzani. In my mid 20’s, studying textile conservation in London, I was walking to the tube from a lecture at the British Museum and in the window of Sotheby’s was a suzani. I had never seen a suzani, a handwoven cloth, hand-embroidered in jewel-coloured silk and I was struck by the glowing colours and the design with was both perfect and imperfect. I vowed on that day to find out more and to go where that textile had come from.

Many years later in late 2018 I finally visited Uzbekistan, a country of startling contrasts. The architecture is some of the most spectacular in the world. Rising out of the rugged and parched landscape are huge Madrassas and ancient Mosques covered with tiles shimmering in the sun in a million shades of blue. The rich history of Uzbekistan’s artisans is everywhere to be seen. The designs seen in these tiles are repeated in the fabulous carved wood seen everywhere as windows, doors and pillars and lately more utilitarian articles like chopping boards and tables. They are seen in the suzani and other embroideries in an endless variety of colours and designs. They are seen again in the ikat weaving in the eastern part of the country in the Ferghana Valley.

During the Soviet era the traditional crafts of Uzbekistan and Islamic religious practice were banned. Uzbekistan is still generally a secular country with a slow revival of Islamic religious practice. It is hard to believe that the practice of embroidering suzani and ikat weaving really stopped during this period. As one travels across the country there are spectacular textiles all around you.

I began my trip in Tashkent and drove across the mountains to the Ferghana Valley. The town of Margilan is the centre of Ikat weaving in Uzbekistan. This ancient city celebrated its 2000th anniversary in 2009 and remains a bustling centre of commerce today. The weekly markets are full of spectacular ikat fabrics woven in silk or cotton in plain weave, silk satin and silk velvet. The fabrics are woven on traditional looms in a narrow width of around 40cm. The variety of colours and designs seems infinite. The quality of the weaving was exceptional. We visited some weaving workshops where we saw warps being tied on an automated device with sticky tape, a method I had never seen before. We saw hanks of warp being dyed and overdyed to produce the rich colours seen in the fabric. In the places we visited generally women seemed to process the silk and weave while men undertook the dying of the threads. The market in Margilan is astonishing in its scale and the excellence of the fabrics.

Returning to Tashkent we called in to a small local store in a market town called Chust to buy some Tubeteika, the black skull caps worn by men all over Uzbekistan with varying designs from region to region. Seeing our enthusiasm, the store owner asked if we would like to visit the home of the embroiderers in a nearby village. It was experiences like this that made travel in Uzbekistan so special. This family lived in a modest house with a beautiful central courtyard full of pomegranate trees and flowers. They bought out their embroidery and demonstrated for us. They then fed us with fruit, nuts and other treats before inviting us for dinner and then to stay the night!

We spent a night in Tashkent, a pleasant modern city with some interesting museums, traditional buildings and monumental buildings in the grand soviet style. There is public art, wide streets and gardens. From there, we flew west to Nukus. Nukus is famous for the Savitskiy Karakalpakstan State Art Museum. This museum houses over 95,000 items. It has one of the best collections in the world of banned avant-garde soviet art from the 20’s and 30’s. It also houses a rich collection of ethnographic and archaeological material. It is an astonishingly large and fascinating collection.

Leaving Nukus we began what would be two weeks spent driving for 100’s of kilometres along the narrow, bumpy and unsigned road that was once the route of the old silk road, to Khiva, Bukhara , Samarkand and Tashkent.

Our first stop was Khiva, a historic walled city that seems to rise out of the landscape like a glorious mirage that happens to be real. Wandering the streets of Khiva, we heard music played on traditional instruments, saw the range of famed Khiva fur hats and saw many textiles including silk cross-stitch embroidery, suzani and rugs.

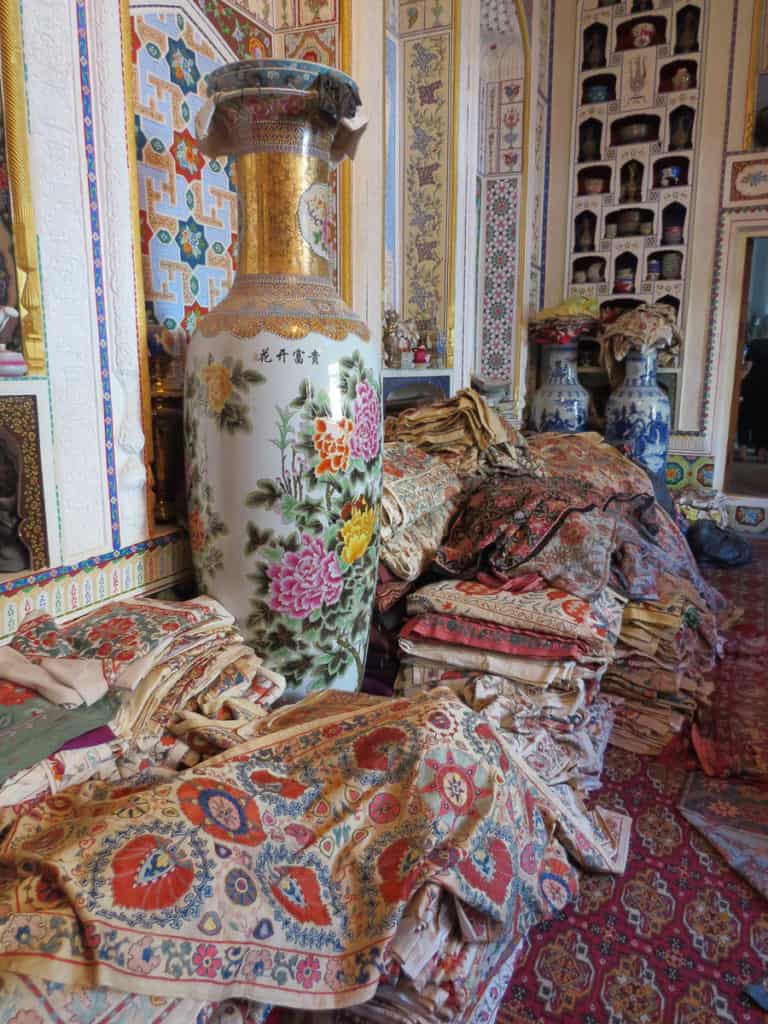

Our next stop was Bukhara, a city with magnificent architecture which is now a major centre of handcrafted textiles. Traditionally there are strong and identifiable design differences reflecting the place of manufacture of suzani in Uzbekistan. I was not able to determine how much of this regional difference design influence still exists. These hand-embroidered cloths are made in outlying villages and workshops and brought to markets in the old town for sale. It is illegal to export antique textiles from Uzbekistan and antique suzani and other embroideries from Uzbekistan and throughout Central Asia now fetch high prices at auction in the west. It was interesting to see textiles in museums to see the changes in the quality and style of the stitching over time. There are still excellent quality new embroideries being made. Generally, the dense roundels seen in older suzani are now seen as often presumably because of the time taken to produce such masterpieces. We were able to meet some embroiderers and see them working. There has been a change in recent years away from Bukhara couching worked with a needle and seen in older suzani towards chain stitch embroidery worked with a tambour hook or crochet hook which is quicker to work. This has resulted in a more open weave ground fabric becoming popular as it is easier to work with using this technique. However, there are high-quality pieces using both techniques readily available in Bukhara.

Finally, in Samarkand, there is the spectacular Registan. This architectural wonder is still home to stalls selling handmade textiles after 500 years. The buildings are part of the legacy of the Turco-Mongol king, Timur, revered as the heroic founder of the nation in modern-day Uzbekistan. Timur’s building bears the proverb: “If you want to know about us, examine our buildings.” These buildings were the result of the coming together of craftsmen and builders from across the empire in the late fourteenth century. Their influence would range far and shape the character of distant cities. The Safavid monuments of Persia and Mughal architecture in what is today Pakistan and India drew inspiration from here. The Imam mosque at Isfahan and the Taj Mahal at Agra also show traces of the Registan.

As with the architecture, the influence of Uzbek design and textile traditions can be seen in the textiles of surrounding countries. These distinctive designs have continued to be produced over many centuries. Uzbekistan has a unique and rich artistic heritage that is flourishing. The recent change of government policy to open the country to tourism will create opportunities for these artisans to interact and work with others across the world once more.

I travelled to Uzbekistan on an architecture and textile tour in a small group of six like-minded people with Boutique Tours and Travel, and I would like to acknowledge our local guide Mubashira who shared her extensive historical knowledge and her own personal story to make my experience in Uzbekistan so exceptional.