Passent Nossair returns to the refreshing gardens of El Harraneya in Giza, Egypt, where she learns the remarkable story of Wissa Wassef, whose belief in the inner creativity of children helped build a weaving workshop of international renown.

(A message to the reader in Arabic.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

Through the eyes of a three year- old girl, this place was cool heaven 🥰. After a long visit to the Saqqara step pyramid, picking pebbles from the ground, running everywhere in the vast sandy space, she felt the heat of the blazing sunshine. She climbed on her dad’s shoulder, seeking a breeze of cool air, only to discover she was even closer to the fiery midday sun. Overcome by the heat, they called an end to the visit. After a short ride in the car, they reached a primitive village, covered with fields of green, as far as the eye can see.

As soon as they entered, it seemed like a welcoming garden, with swaying palm trees, beautiful plants and exotic flowers! A cool breeze caressed the little girl’s cheeks, and she felt transported to a different dimension! The heat of the sun had miraculously evaporated, boosting her energy. Once again she kept hopping, running and giggling.

She and her family were led to a hall within the buildings in the garden to the neat sitting area, which had a huge brass-rounded tray set on wooden table legs to hold their snacks brought from home. In front of the table, a big rectangular window overlooked a breathtaking view! Like the frame of a great painting, it captured the timeless, infinite horizon, the beautiful botanical garden, the evergreen fields of the village, ending at the foot of the golden sands surrounding the Great Pyramids at Giza!

There they stood, at the very place where they were built, thousands of years ago. Next to the sitting area, were the halls of the weavers!

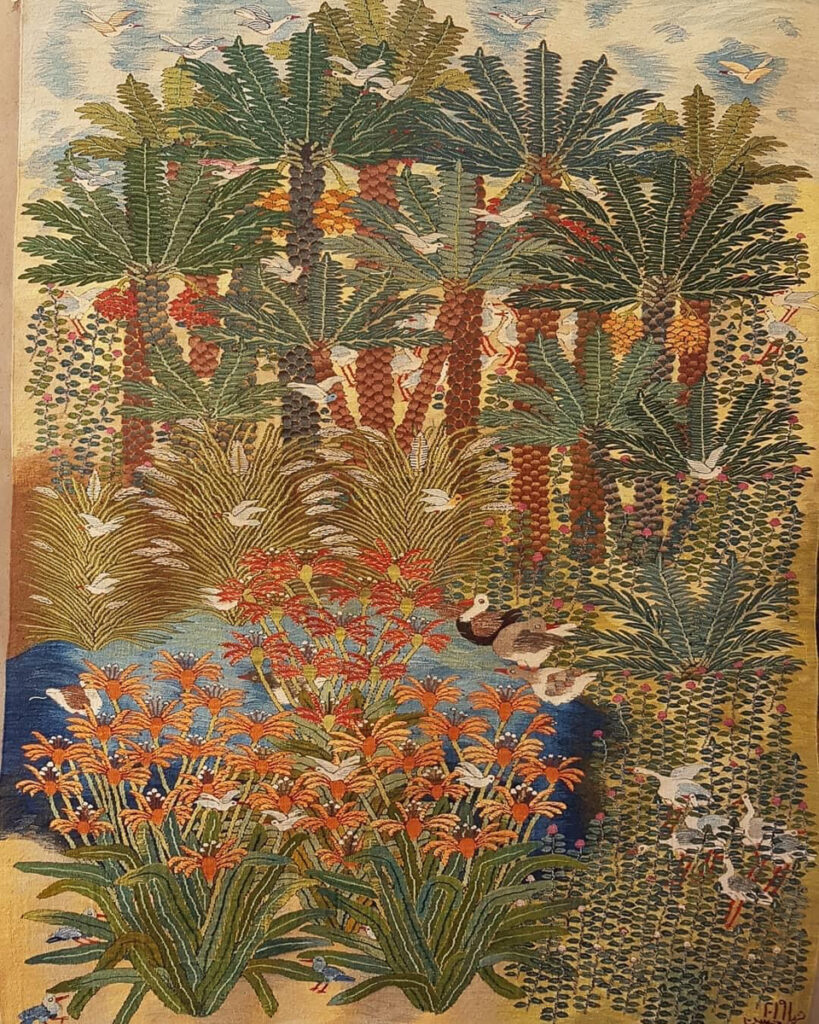

What a vivid and exciting sight! All these youngsters, busy at work, weaving colourful tapestries. The little girl sat next to them overwhelmed with the beauty of their work. Encouraged to mingle with them because they were young teenagers, she thought they could become friends. To her, they were playing with colours.

With a glimmer in her eyes, she wished she could join them 😃…

This is not a dream! This is a blurred memory of a day I never forgot! It remained with me until I was thinking of going back to that same place again—thirty years later!

- Reda, weaver at Ramies Wissa Wassef Art Centre

- Mahrous, weaver at Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Centre

A visit to the Wissa Wassef Centre was somewhat puzzling to me, probably because I was expecting to wander in the green fields and reach the oasis of a lush, blooming garden in the centre. It was still so vivid in my memory.

A large sign indicating my destination brought me back to reality. Where are the endless green fields, the serenity of another universe?

Instead of the fields, a concrete multi-storey jungle stood, blocking the view of the horizon. I parked my car at the gate, and with my first step into the garden, all the memories came rushing back. I felt the same cool breeze, the friendly and familiar atmosphere, the same welcoming aroma of the place with its palm trees, botanical plants and vernacular architecture.

This visit was not seen through the eyes of a child. This was a visit seen through the eyes and mind of an expert in handicrafts business development and design, who always admired and highly appreciated the successful paragon, the methodology and the legacy of the place.

Its founders & current owners and above all, those who executed the ingenious project—the weavers!.

Thank god I asked my friend to accompany me or I’d have been lost in daydreaming.

We met with Mr Ikram Nosshi, director of the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center in Harraneya. Ramses’s son in law, (husband of Suzanne Wissa Wassef, the eldest daughter of Ramses ). The couple who passionately took over the responsibility of the centre after Ramses and his wife Sophie—until now.

Nosshi generously gave us two hours of his valuable time. He recounted the story of Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Centre, explaining the philosophy behind it, with all the details of the theory and experiment, from the very beginning to this day.

- Ramses & Sophie

- Ikram and Suzanne

Ramses Wissa Wassef graduated from L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Paris. He taught design, history of art and history of architecture in the School of Fine Arts in Cairo. He also headed the Department of Architecture between 1967- 1971. His many prominent students included: Shadi Abdel Salam, a distinguished Egyptian film director/ screenwriter/ costume and set designer; Adam Henein, one of the foremost Egyptian sculptors; Nagy Shaker, a puppeteer and artist; Ihab Shaker a cartoonist and illustrator; and Abdel Ghany Abu Al-Anieen, Pioneer of the Press layout Director and head of Folklore Centre.

Ramses had a strong conviction: “No matter the background or social status, every child is born with creative energy! If not explored and exercised at the early age of 10 to 11 years, the child may grow up not realising that he possessed it at all.”

To prove his theory, he decided to experiment with children, as they have no boundaries, no limitations and no responsibilities. In 1952, Ramses chose to start his experiment in a simple village, with no particular craft except farming and its associated activities. It was a primitive agricultural environment and minimal influence of city lifestyle. So he set his mind on the village of Harraneya in Giza.

As for the children, he had not set criteria for choosing them or a filtering process. In fact, they chose him!

As usual, children were the first to greet any strange car coming into the village. They gathered around him, with bright and curious shining eyes, trying to figure out, what are the intentions of their new visitor. He bought half a feddan (2100m2), on which he established a playground for the children and built a room which he turned into a clinic with the help of his brother who was a physician.

It took him almost two years of concentrated effort to break the ice with the children. He was no longer a visiting stranger. The group of 15 boys and girls who kept meeting with him every week, were the first group he introduced the new craft to. The children of 1952.

Before he started with the children, he taught himself weaving. He wove an ox, an ancient Egyptian sacred animal, a tree and some geometrical patterns, using the five natural colors that existed at the time: white, beige, grey, black and madder. His early tapestry can still be found today in the centre’s museum.

Ramses chose the craft of weaving as a vehicle to his experiment of creativity. Because it is a noble craft, it is challenging. It would stretch the children’s limits, trigger their eagerness and develop their sense of achievement. Weaving is a slow craft, it would allow the children to process their surrounding environment, access their folkloric and heritage reservoirs, tap into their minds and grasp the true, genuine inspiration.

Ramses implemented three rules at the centre:

The first rule was: Never tell a child what to make; there is no preliminary design to the tapestry. He wanted each child to design his/her own idea, allowing the authentic creative energy to flow.

The second rule was: Although he was a professor of history, art and architecture, he never showed the children other forms of art or taught them the history of art. He did not want any external or foreign influences. His aim was to unleash their imagination and depend on their own pure source of inspiration.

And the third rule: Never criticise the children. No one was allowed to criticise them, not even the visitors to the centre. He did not want any constraints or pressure to hinder the free flow of their creative energy, and the evolving process of their talents.

It was an experiential learning process, full of exploration, observation and imagination. Through this process, Ramses was seeking proof of his theory. He had to set a sustainability mechanism to maintain his project and keep it going. His approach for sustainability followed in many directions.

First of all, he needed to ensure the availability of materials, so he used local raw materials, the Egyptian cotton and local sheep wool.

Secondly, he believed in going back to the roots in order to succeed, so he researched ancient natural dyeing plants and methods which existed in Egypt and elsewhere. Following the examples of the Coptic and Islamic textiles, he reintroduced them and let the villagers plant and harvest them and then use it in dyeing their wool.

Sheep wool came in a few natural colours: white, beige, brown, grey and black. Ramses then found Indigo or (Nila) as they call it in Egypt, resembling the pure dark blue colour and name of the Nile. The weed used to grow naturally on the Nile banks after the flood. Up to 1963, it was one of the cheapest kinds of dye, the reason why blue was the colour of the prisoners’ uniforms. Compare the price to nowadays which has reached $1400.

He used root madder for dark red-orange colour, reseda luteola for yellow and pecan leaves for beige.

In the beginning, Ramses’ main goal was not reviving the lost craft of natural dyeing. But he appreciated it was a by-product of the weaving craft.

Nosshi explained, “up till today in spring, sometime in May, after harvesting the dyeing plants, we do a festival of colour. This is when the weavers dye the wool, mixing and matching the different shades of fleece with the different dyes to get a very rich and vivid spectrum of colours.”

In 1952 Ramses started his experiment investing his own money. From day one he paid the children for their time and efforts. This showed the children how he appreciated their work, and established their sense of value and importance of their work.

It took the children of 1952 almost 5 years of nursing the seed of their creative energy to soar and evolve and take the form of proper production. In 1958 he had the first tapestries exhibited at the International Exhibition in Basel – Switzerland. This is when his experiment was noticed by everyone. He got invited everywhere, including England, France, Italy and the USA.

To guarantee the preservation of his model, Ramses reinvested a good portion of the profit in the centre. He would buy another piece of land, increase the number of looms and invite more children to join the Wissa Wassef team. He even taught the boys the basics for vernacular construction, with the hope that they may build their own homes later.

Of course, this experience strengthened their sense of ownership towards the centre. Seeking proof that his theory could be applied to different crafts, other than wool tapestries and cotton fine horizontally weaved tapestries, he introduced batik and pottery.

The centre was a subtle change agent not only to the children as individuals but to the whole community of Harraneya.

In a village community whose only endeavour was agriculture, the norm for children, where they had to become either peasants like their fathers or housewives like their mothers, Ramses paved for them another path.

He challenged the culture and norms of Harraneya. At the time Ramses started, girls were not allowed to work except sometimes in the fields with their fathers.

The Centre established women’s empowerment and gender equality: both girls and boys joined the centre and for the first time girls earned money. They were able to help their parents, save money for their wedding trousseau and help provide for their families after marriage. Boys and girls, men and women earn equally depending on the work.

Paying the children at a higher rate than those working in the fields, proved to the villagers the benefit of sending their children to the centre. Moreover, the parents were assured that their children were participating in a serious line of work.

Other qualities gained by the children were confidence and fulfilment. They attended more and more exhibitions and received more and more invitations. It was more than the opportunity to show their distinctive production, but the weavers also dressed in their authentic traditional clothes and brought along small-sized looms to showcase their work live right in front of bedazzled audiences.

- Egypt, tapestry by Ali Selim weaver from the 1st generation, the children of 1952

- The ox , tapestry by Ramses Wissa Wassef

The praise, high dose of encouragement and recognition they received, boosted their self- esteem. They were proud and satisfied with their achievement. The legacy of the Centre grew bigger. Every event was inaugurated by a notable figure, including the King of Sweden and the late Princess Diana. Many VIPs visited the centre, John Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Jacques Chirac, Anwar Sadat, Jimmy Carter, Henry Kissinger, etc.

At some point, the Wissa Wassef tapestries were the number one choice of the Egyptian ministry of foreign affairs for formal gifts. Major museums and institutions own collections of their tapestries, the Cairo Opera House, the Metropolitan Museum, the British Museum, Victoria and Albert, Royal Museum of Scotland, Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, etc.

All of this outstanding success came true with determination and persistence. Because they were not business-oriented, they never catered for market demand. Their aim was, is and always will be to perform genuine creative work.

This was the Wissa Philosophy!

To take the successful model a step further, Ramses went out of his way to accomplish formal requirements and permits, which led the weavers to join a pension system.

A social role conducted by Sophie Gorgi, Ramses’ wife, was to introduce home management, health and hygiene basics. It must be remembered that the children were illiterate and like a typical Egyptian mother, she had a role in the girls’ weddings and marriage arrangements.

She even encouraged fair competition between the girls, and the rewards were items for their new homes like trays, linens, etc. They kept these for their bridal trousseau.

After the death of Ramses in 1974, Sophie was in charge of the centre up to 1983 when she handed the responsibility to the second generation. In pursuit of another proof, after the outstanding accomplishment of the first generation of weavers. Ramses wanted to validate his theory once more, with a new batch of children.

A new group joined the “Children of 1972”. This time it was led by his daughters, Suzanne was in charge of wool weaving, and her sister Yoanna in charge of fine cotton weaving. Suzanne mentored the second generation until 1983 when she and her husband started managing the centre. With the same core philosophy set by Ramses Wissa Wassef, they only added a few minor changes to the management style.

International exhibitions and events are still their main outlet for sales. The Centre website and the online sales and being on social media were definitely an important addition and helped in the Centre’s exposure, keeping it always in the limelight. They set a contingency plan. Any extra profit would go into a fund, as security against the occurrence of any unexpected adversity.

A tour to the work halls of the Centre revealed a mesmerising work in the making. We met two weavers from the second generation, Reda and Mahrous. Reda greeted us with enthusiasm. She was a proud weaver working on a scenic tapestry in front of the loom, which still preserves the beauty of Egypt’s rural identity, featuring the traditional galabeya and the flowing headscarf of the peasant fellaha. “I came to this centre when I was 10 years old. I was fascinated from day one and I never left,” she laughed.

Reda is among the second generation of weavers in the centre, and a mother of three. “I really wanted my children to come and work here. They liked the centre but they were not interested in the work. This generation does not have any patience. Now they regret it! However, my grandchildren love weaving and love seeing me work on the loom so I am guessing there is hope,” Reda told us with a gentle smile on her face.

Mahrous, who followed the steps of his aunts, two weavers from the first generation, is another artist who began his weaving journey at the age of eleven. He takes pride in learning how to stitch from day one. “The beginning is always challenging because it involves a lot of trial and error, but in my case, with every tapestry things would improve,” Mahrous told us.

Mahrous wove in front of a live audience on many occasions in different countries. His very first exhibition was at Villa Borghese in Rome at the age of 17. “I worked in farming and in carpentry but I was never happy. This is where I feel I belong the most,” Mahrous said.

By mere chance when we were on our way to the Centre’s museum we met Suzanne, who offered to take us on the tour herself. “I’m like a mother, I have followed them since childhood. I know their interests, shortcomings and points of strength. I got to understand them and along the way, I taught myself how to interact and approach each one of them.” Suzanne briefed us while showing us the tapestries and explaining the style of each weaver and the story behind every tapestry. She knew them by heart!

When asked about their source of inspiration especially after such drastic change in the village environment? “Sometimes we take on trips, and of course we have our garden.!”

The Ramses Wissa Wassef Centre is a living testament that one can find beauty, inspiration and talent in the simplest and purest of places, inside children’s hearts and minds when nursed properly.

Perhaps his legacy wouldn’t have survived without the humility and resilience of the Nosshis, who not only carried Ramses’ torch but also stayed true to his values and belief that art can change lives. They remained true to his philosophy.

A philosophy of his own!

A Wissa/Sophy!

Author

Passent Nossair is a British Egyptian, currently living in Cairo. She graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cairo and exhibited in several art exhibitions. She has been handicrafts business development consultant and designer since 2007, in different entities, including EU projects, the Egyptian ministry of trade and industry and Aga Khan Development Network. She is a Member of The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the World Craft Council (WCC), Africa-Egypt.

Passent Nossair is a British Egyptian, currently living in Cairo. She graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cairo and exhibited in several art exhibitions. She has been handicrafts business development consultant and designer since 2007, in different entities, including EU projects, the Egyptian ministry of trade and industry and Aga Khan Development Network. She is a Member of The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the World Craft Council (WCC), Africa-Egypt.