Guy Keulemans introduces designer Ivana Taylor, whose work reflects the creative potential of wrapping.

(A message to the reader.)

Wrapping is used in many cultures as an act of care, giving or protection. For example, the Japanese have furoshiki, the tradition of wrapping presents between friends and neighbours in reusable printed cloth and warazaiku, the use of rice straw to wrap agricultural products. Furoshiki is praised as an example of sustainable gift-giving. Warazaiku, due to its association with rice framing, has a deep connection to the Shinto spirituality of the country.

Around the world, mums, dads and nurses swaddle babies. Due to extreme cold, swaddling babies is particularly popular in Mongolia. Babies are swaddled in two or three layers of thin cotton cloth, followed by multiple layers of blankets and then bound for the whole day.

Personally, I like to restore and modify old road bicycles. Wrapping the handlebars is the very last stage and the most satisfying. There is a tangible feeling of completeness, of conclusion, a sense of locking off or closing an open project.

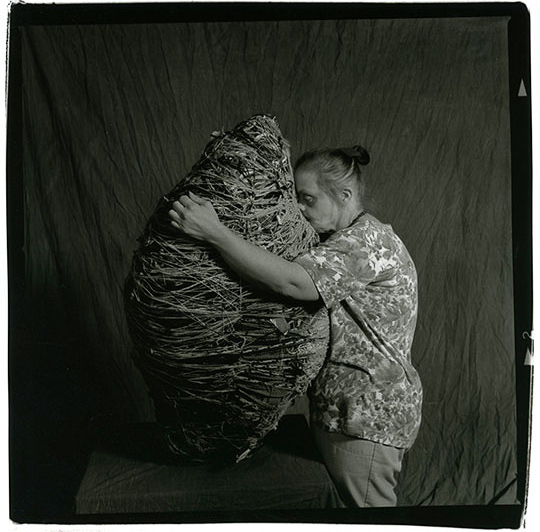

This yearning for completeness, perhaps closure, motivated Judith Scott’s artistic journey. Born in 1932 with Down’s Syndrome and deafness, the latter undiagnosed for many years, by age seven she was considered troublesome and uneducable. She was separated from her twin sister and placed in a series of poorly managed care homes. Four decades later Scott learnt to self-treat her depression and loneliness by wrapping discarded textiles, loose and stolen fabric, anything she could get her hands on, into giant huggable sculptures. By the time of her death, she was arguably the most celebrated outsider artist in America.

These are just a fraction of the various ways humans have wrapped. The book Wrapping and Unwrapping Material Culture: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives (2014) details wrapping practices across five continents and three millennia, including Celtic and Viking burial practices, wrapping in European fashion, and the wild silk wraps of the Dogon people of Mali. Such practices are distinct, but connected by an art that is intrinsically human.

When I saw the first wrapped furniture from designer Ivana Taylor, I recognised something unique in its expression, but also something familiar and deeply grounded in human culture. I think it’s quite easy to imagine an early human ancestor experimenting with wrapping palm fronds or grasses around the same time of language and tool use development. Which is just to say that wrapping craft may go back deep into evolutionary history.

What does wrapping do? It generates form, it alters surface, it conceals, it protects. It provides closure, it gives strength. It even changes how we perceive what’s under wraps. It creates mystery.

Taylor is herself inspired by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. This is an interesting comparison not just because of visual similarities, but because I recognise a shared intuition for how to dynamically wrap complex objects. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping of Little Bay in Sydney in 1969 responded to a similar problem Taylor encountered wrapping gnarly tree trunks in her experimental graduation works: how should you wrap nature? Conversely, Taylor’s method of wrapping her workshop-fabricated furniture is ordered and rhythmic in its repetitions, similar to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Reichstag (1995) or L’Arc de Triomphe (2021). One characteristic feature of wrapping these works is planning. Wrapping is a premeditated sequential craft. Christo and Jeanne-Claude spent years planning their temporary installations. Taylor likewise wraps her objects as a skilled designer: with visual logic and creative composition.

Taylor’s wrapping is more permanent than Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s, but it carries a similar capacity: what can be wrapped can be unwrapped. Following her interest in sustainable products and her knowledge of design for disassembly, Taylor’s designs can be unwrapped and re-wrapped for maintenance or repair, potentialising long service life. She says re-wrapping is teachable.

Unwrapping is not simply the reverse of wrapping either, it has its own qualities of aesthetic and conceptual revelation (Wieczorkiewicz, 2005). These may even be only potential, sensed just through possibility, without any actual unwrapping. This is the mystery of wrapped objects. It’s well expressed in the secrecy surrounding the sacred mirror of the goddess Amaterasu in Ise, Japan. Said to be wrapped in a succession of cloth bags, as soon as the outermost bag rips or shows signs of wear, the mirror and its bags are placed all together into a new bag. Most of the bags have not been seen for hundreds of years, the mirror perhaps not since 982 AD (Dumpert, 1998: 30).

The wonder of wrapping and unwrapping, the delirious experience of becoming entwined within the fabric of the ancient past, is famously captured by the ancient Egyptian mummy. The mummy holds special status as a wrapping tradition at its most arcane. It’s not entirely tangential a topic for a furniture designer, as it is from the ancient Egyptians that we have the oldest surviving examples of furniture, including backed chairs, beds and sophisticated folding x type stools. Immaculately preserved in tombs, it is thanks to the Egyptian concern for the wellbeing of their dead in the afterlife that we have such artefacts, all others lost to the rot of time.

Mummification practices began very simply in ancient Egypt. For example, a shawl might be simply dipped in resin and draped over the body for a desert burial. But practices became increasing articulated for pharaohs and the wealthy. The horror movie cliche of a ragged, bumbling mummy trailing loose wrapping ends isn’t very fair. The most sophisticated mummies have complex, elegant wraps, such as seen in the square-faced mummy at the Louvre in Paris, a wealthy merchant from the Ptolemic period.

The mummy is equally respected and mocked for its pre-scientific attempt to extend life beyond death. I see the resemblance to Taylor’s work more than visual or structural, but conceptual: Taylor is also concerned with matters of life and death in objects. Her first wrapped work from 2016 completely encased an old stool that was destined for landfill, reinvigorating its appearance and giving it new life. When Taylor re-created this work for the start of her associateship at the Jam Factory in Adelaide, her colleagues gasped at the sight “…it’s a mummy!”

The thing of importance with the mummy (which also happens to be the thing disrespected by 20th-century museums that displayed the mummies unwrapped, their desiccated faces stripped bare) is that it is the wrapping itself that comprises the logic and magic of the mummy, not the body underneath. The framing of mummification as a historical technique of embalming, that brings a body into the future, is a museological construction. Rather, for ancient Egyptians, mummification was a literal act of magic that guided the soul into the afterlife.

To return to Taylor’s work, I think the point is hope. We wrap many things—presents, objects, even the dead—with care, logic and planning. These qualities carry hope into the future. For a wrapped birthday or wedding present, that future may only be a few hours or days away, but nonetheless, the wrapping becomes a vessel, carrying dreams forward in time.

This is an act of consideration for others. Furniture and homewares in this context of life and death may seem out of place, but it’s not the case. Modern lifestyles encourage us to buy often and barely care for our possessions. Homewares last just a few years in some cases. But environmental imperatives, the waste crisis and the health of the earth create an urgency for better consumption, for the wellbeing of all. Taylor fulfils this need with a delicate of act of care, expressed by wrapping and guided by design.

Ivana Taylor’s solo exhibition Reframe runs from 25 November to 19 December 2021 at Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert.

References

Dumpert, J. (1998). In the Presence of the Goddess: Bowing Before the Mirror in Shinto. Journal of Ritual Studies, 12(1), 27–37.

Harris, S., & Douny, L. (2014). Wrapping and unwrapping material culture: Archaeological and anthropological perspectives. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Wieczorkiewicz, A. 2005. “Unwrapping Mummies and Telling Their Stories: Egyptian Mummies, in Museum Rhetoric.” In Science, Magic, and Religion: The Ritual Process of Museum Magic, edited by M. Bouquet, M. and N. Porto, 51–71. New York: Berghahn Books

About Guy Keulemans

Guy Keulemans is a designer, artist and researcher producing critical objects informed by history, sustainability and experimentation. He has exhibited around the world and has multiple works in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Guy is represented in Australia by Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert.

Guy Keulemans is a designer, artist and researcher producing critical objects informed by history, sustainability and experimentation. He has exhibited around the world and has multiple works in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Guy is represented in Australia by Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert.