Jane Perryman From Light to Dark From Dark to Light 2021, ceramic, 13cm x 12cm x 12cm; photo: Jane Perryman

Sebastian Blackie reflects on the celestial ceramics of Jane Perryman and Tom Hall writes about the accompanying soundtrack by Kevin Flanagan.

British artist Jane Perryman regularly visits the Norfolk coastal mudflats. They are under two hours drive, door to shore, from her studio. The tide is full to the brim with fresh saltwater; a shining edgeland of succulent samphire, purple sea lavender, marsh-mallow and salt meadow sedge. At our feet urgent, bloated rivulets, the colour of tarnished silver, advance towards us across the dusty sand. Without warning, they check, then wilt, as if in doubt, and reluctantly retreat. Soon there is just a dark stain like blood on a battlefield; a visual memory of the seas failed bi-daily invasion of the land. We have just seen the Earth move.

For the last year, Perryman’s ceramics have been inspired by a similar visceral sense of celestial movement. She has used the changing astronomical timings taken from a year. Once a fortnight, over twelve months, she has taken five measurements a day: civil twilight (dawn), sunrise, solar noon, sunset, and civil twilight (dusk) from the top of a hill on her property. There under a large oak tree, she would record her feelings and observations with text and camera. It seems more a pilgrimage than a study involving rising before first light as well as being there to witness the remains of the day, through rain, frost, fog; smelling the baked earth, as the birds fall silent at the end of a hot summers evening or shivering in the morning cold when she startles a deer unused to human presence so early.

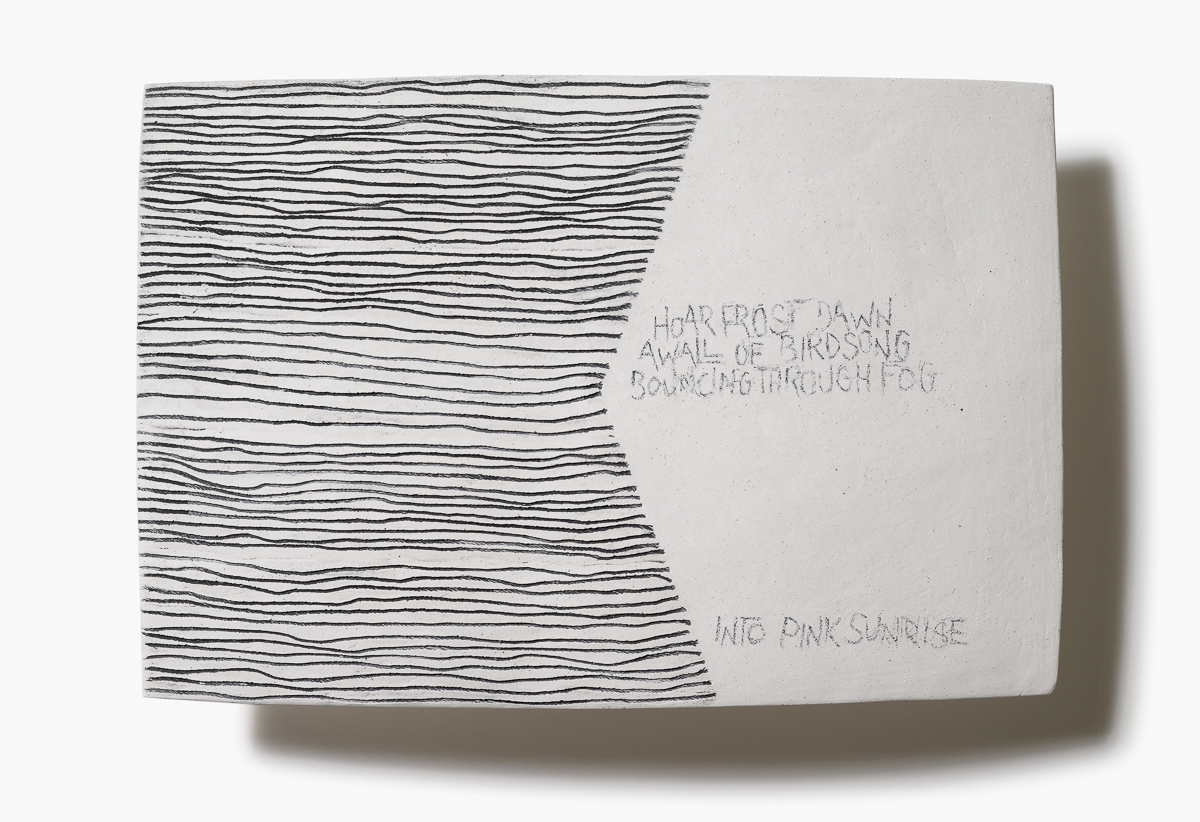

The experience and measurements have led so far to three distinct but interrelated bodies of work each comprising twenty-six individual pieces in sequence. The first group are upright and cylindrical but actually oval in plan. These twist and become increasingly contorted reflecting the year they represent. They are placed in two rows of thirteen all with their bases aligned on the north-south line. One row represents the angle of sunrise over six months of the year the other represents the angle of sunset for the other six months. The second group Perryman worked on are twenty-six wall mounted rectangular slabs of equal size with the varying proportions of light to dark described in engraved lines inlayed with oxide. They also incorporate short bits of script, a kind of diary. These record incidental events that occurred on her repeated walks to the brow of the hill. The third piece is made with small press moulded round-bottomed bowls decorated with engraved and inlayed lines that reflect the angle of solar noon across the four seasons.

All the work is hand-built and unglazed with Perryman’s signature minimalist precision and care for detail. But they feel more fragile and ethereal than her earlier substantial burnished and smoked work for which she has an international reputation. The engraved lines on the new work have a human irregularity to them but also a sense of purpose, reminiscent of the path that she has worn on the regular visits to her observatory. Laid out in sequence the spaces between each piece and the shadows they cast are as important as the pots themselves. It is silence as well as sound that makes music. They are an example of the material world alluding to the immaterial.

Jane Perryman, From Light to Dark From Dark to Light, 2021, making in the studio, photo: Douglas Atfield

A clue as to at least one of the sources of this project can be found on the wall of Perryman’s studio. It is a photograph of the eighteenth-century observatory Jantar Mantar built in Jaipur, India, one of many amazing structures from antiquity onwards that seem to represent human desire to understand the stars, along with the Maya pyramid observatory at Chichén Itzá, the Kalokol pillar site, Turkana, Kenya, Nabta playa, Egypt and Britain’s Stonehenge. With our modern educated, post-enlightenment, minds we may be tempted to view these structures as primitive scientific instruments. Perryman’s work suggests something else. Like her pots, they may measure and record but they are also about participation and an acknowledgement of a power much greater than our own. Her earlier work with their rounded forms and sensual surfaces say “look at me” this works points to the stars. They are vessels in service.

When artists like Perryman with a background in ceramic craft develop practice that might resemble fine art, it is tempting to apply a new vocabulary. But terms like installation, intervention and assemblage seem pretentious, in search of status rather than understanding. Perhaps “gatherings” might be a more appropriate alternative to installation. It accurately describes her creative process and is softer, more in keeping with the medium and methods. It seems to build on existing ceramic language, not borrowed from another discipline and helps identify what is particular to ceramics and pots.

An important aspect of potting that the non-maker may not be fully aware of is repetition. We make the same hand movement over and over again. We ritualistically prepare the clay with repeated actions. Without thinking we handle the clay differently at each stage of the making again and again. Our bodies become imprinted so that we create as much with physical as intellectual intelligence. Because of this, potters are highly attuned to subtle differences that may be subliminal to others. Clay has no discernable form but it has an enormous range in character when worked that will determine the quality of the final piece. Perryman’s current work could be understood as an installation but this emphasises its interjection into a space. “Assemblage” does not capture the precise sequencing that underpins this exhibition. More value may be found in looking for the relationships between each of the individual elements that make up these works.

Jane Perryman From Light to Dark From Dark to Light, 2021, ceramic, 32cm x 20cm x 12cm; photo: Douglas Atfield

As well as potting, Perryman has had a parallel career as a Yoga teacher. Perhaps this accounts for the fine sense of balance present in all her work and a feeling for arrested movement. The twisting cylinders are like stretching torsos so that we feel, as well as see, the form. In the natural light of Perryman’s studio, their shadows move across the surface of their partners as the day progresses and the play of dark silhouette on a similar white shape is like a dance.

Perryman is working towards a show at the Ruthin Centre for Applied Arts, North Wales next April. The event promises to be more a performance than a conventional exhibition as it will be accompanied by music specially composed by Kevin Flanagan to accompany the clay work and lighting that synchronises with the sound. Flanagan’s piece adopts the same structure using 26 segments, which progress in time to reflect the varying length of daylight. He uses ambient bird song, wind and rain captured when accompanying Perryman on her observations and harmonics based on the electromagnetic signature of the Sun. The composition captures the intimacy and specificity of place with the vastness and mysteriousness of space.

It is not the first time Perryman and Flanagan have collaborated. Containing Time, a series of clay vessels that physically incorporated materials gathered over a year from many different locations was also accompanied by his music. Flanagan uses the sound of each vessel when struck, whose pitch differs due to the burnt-out traces of shells, wire, coffee grounds… Containing Time seems to have been both a transition from Perryman’s former object-based work and a foundation for her present project From Light to Dark From Dark to Light that deals with the universal and the specificity of time and place.

Jane Perryman, From Light to Dark From Dark to Light 2021, ceramic, 21cm x 29.5cm x 0.5cm, photo: Douglas Atfield

I am standing on a bank of razor shells that wanders into the distance to my left and right. They mark today’s high water on Holkham beach, one of the places Perryman celibates in Containing Time. It is a place where land, sea and sky are in continual flux. It is an hour past low tide but the shoreline is still a mile away although the surf can just be heard. The wind is light but raw and we hunch our shoulders against its bite. Last night was The Cold Moon, the last full moon before Christmas, but cloud has obscured both sun and moon for some days now. Nevertheless, I think and feel differently about this place because of Perryman. That’s how art works; as Primo Levi has written “as with all spiritual food one is left both satisfied and more hungry than before”. Suddenly a Tiger Moth roars overhead. Its double wings strutting and fretting, it makes several acrobatic passes on its aerial stage, full of sound and fury, before disappearing as rapidly as it arrived. A thousand raucous geese, on winter break from Finland, resettle on the salt marsh and the landscape returns to its universal business.

About Sebastian Blackie

Having been involved with ceramics throughout his career Sebastian Blackie’s practice has recently turned to the less physically demanding creative writing and photography. He has undertaken a number of ceramic residences including The National Art School, Sydney. FLICAM, Shangyu and Jingdezhen China and the Studio of Ryoji Koie Japan. In 2004 he was made professor of ceramics by Derby university where he ran a masters in Fine Art, Photography and Film, eventually leading research in the School of Arts (A&D, Drama, Music and Media). He lives in the ancient town of Thrapston, UK on the Cambridgeshire/ Northamptonshire border.

Having been involved with ceramics throughout his career Sebastian Blackie’s practice has recently turned to the less physically demanding creative writing and photography. He has undertaken a number of ceramic residences including The National Art School, Sydney. FLICAM, Shangyu and Jingdezhen China and the Studio of Ryoji Koie Japan. In 2004 he was made professor of ceramics by Derby university where he ran a masters in Fine Art, Photography and Film, eventually leading research in the School of Arts (A&D, Drama, Music and Media). He lives in the ancient town of Thrapston, UK on the Cambridgeshire/ Northamptonshire border.

✿

Elective affinities: Kevin Flanagan’s soundtrack to accompany From light to dark from dark to light

Composer-performer Kevin Flanagan has made a sonic work as part of ceramic artist Jane Perryman’s collaborative project From Light to Dark From Dark to Light. The sonic accompanies the ceramic as one person might accompany another on an outing: there are shared interests and interplay, but also a sense of separate artistic identities. To borrow a phrase notably used by Goethe, we notice “elective affinities” between the two works, but differences too that extend beyond the affordances of the media, tools to fashion and modes of perceptions employed to experience them (sight, touch, sound, heat, hands, eyes, ears, microphones, musical instruments, coffee, clay, noise, clay, wind, text, etc.). Reflecting as it does practices rooted in the twentieth-century avant-garde more recently familiar from cinematic sound design, we might describe Flanagan’s work as a “soundtrack”.

The research and process underpinning the creation of Perryman’s project have been well-documented elsewhere. Experiencing the work is to notice aspects of gradually changing visual and textural form, regularity, organic irregularity, repetition and process. These notions form a good starting point for experiencing Flanagans’ 30-minute soundtrack, heard on an endless gallery loop. This presentation complements the soundtrack’s form, which encapsulates the spiral and palindromic nature of musical pitch and a telescoped, Viconian cyclical year. The 26 divisions within Perryman’s work are also reflected in the sectional temporal form of Flanagan’s soundtrack. (The two accompanied one another into the landscape each fortnight as described elsewhere, he with microphone and digital recorder.) The sonic perceptual divisions are marked by a prominent bass note in the piano, with the duration of each section (between 45 and 90 seconds) and other aspects of the soundtrack being determined by the ever-changing ratio between the duration of night and day.

The other sonic components that make up the soundtrack are readily apparent to the ear. We notice the interplay between the simple piano musical “gestures” and semi-improvised soprano saxophone responses. Speaking in January 2021, Flanagan described an interest in how closely these “are touching upon each other”. We may compare this with the placement between Perryman’s ceramic artefacts in the gallery space. The minimalistic cluster of five repeatedly reordered notes we hear are derived from analysis of the low rumbling drone we sense underpinning the soundtrack, a “sonification” by Professor Alexander G. Kosovichev of data recordings of solar oscillations.

Within the soundtrack, we also hear the lightly struck, gong-like sounds of each of Perryman’s 26 ceramics in sequence and may notice connections to the sounding notes of the piano and sax. Finally, we hear overlapping ambient “field recordings” made during observational sessions as described above. Listening, we notice the rich sonic textures the microphone happened to capture which mirror the lines and traces of natural materials which texture the surfaces of Perryman’s ceramics. Blending with the other sonic elements, we notice textures of wind, rain, aircraft, and birdsong, and are occasionally surprised by the sounds of vocalising Tawny owls, or the happenstance of encountering the human-made sounds of aircraft within the sonic environment.

About Tom Hall

Tom Hall is a UK-based Australian composer, performer and writer on music engaged with both acoustic and live electronic music. His work often combines composed, algorithmic and improvisatory elements involving notions of flow and slowness and fixed works often centre around the human voice and text, including those of author Gerald Murnane. Visit www.ludions.com

Tom Hall is a UK-based Australian composer, performer and writer on music engaged with both acoustic and live electronic music. His work often combines composed, algorithmic and improvisatory elements involving notions of flow and slowness and fixed works often centre around the human voice and text, including those of author Gerald Murnane. Visit www.ludions.com