Michael Williams uncovers a rich material heritage from communal buildings used by Chinese migrants.

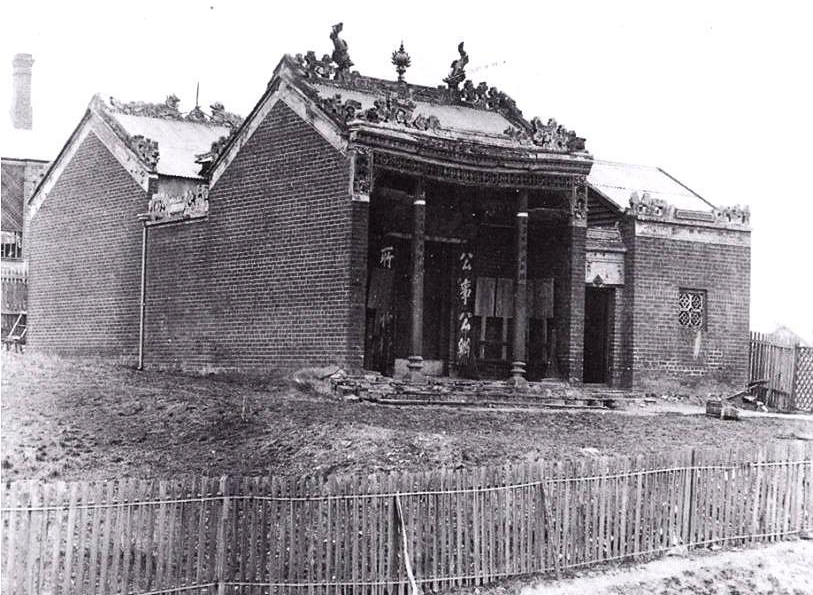

From the moment Chinese immigrants set foot on the goldfields of Victoria and New South Wales, they began establishing places of worship. These early structures, often referred to as “Joss Houses” (from the Portuguese word Deus, meaning “God”) started as calico tents but quickly evolved into wooden and brick temples. At the height of the gold rush, more than a hundred of these temples were built across Australia. Unfortunately, many have since fallen into disrepair or vanished as their communities aged, moved, or converted to Christianity. Fires and other forms of decay claimed most of these temples, and the artifacts they housed were often scattered into the local community, sometimes finding their way into museums.

The building that has now opened is by no means an imposing structure, being of weatherboard and of very modest dimensions. In the Joss House, an altar is raised at the west end, ornamented in a fantastic way with glided emblematical figures, joss sticks, and peacock’s feathers; and over this is a portrait of Quan-woon-Tung, … A pleasant incense rose from the numerous joss sticks burning around, and from a brick stove in front fed by occasional contributions of paper and gold leaf from the hands of the celebrants. Outside the doors were three sets of tables under a canopy, literally groaning under the weight of baked meats, dried fruits and preserves, the greatest profusion being heaped on the table nearest the door. Two large pigs beautifully roasted, with crackling done to a turn, …

Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser, 14 April 1873. p.4.

A Handful of Survivors

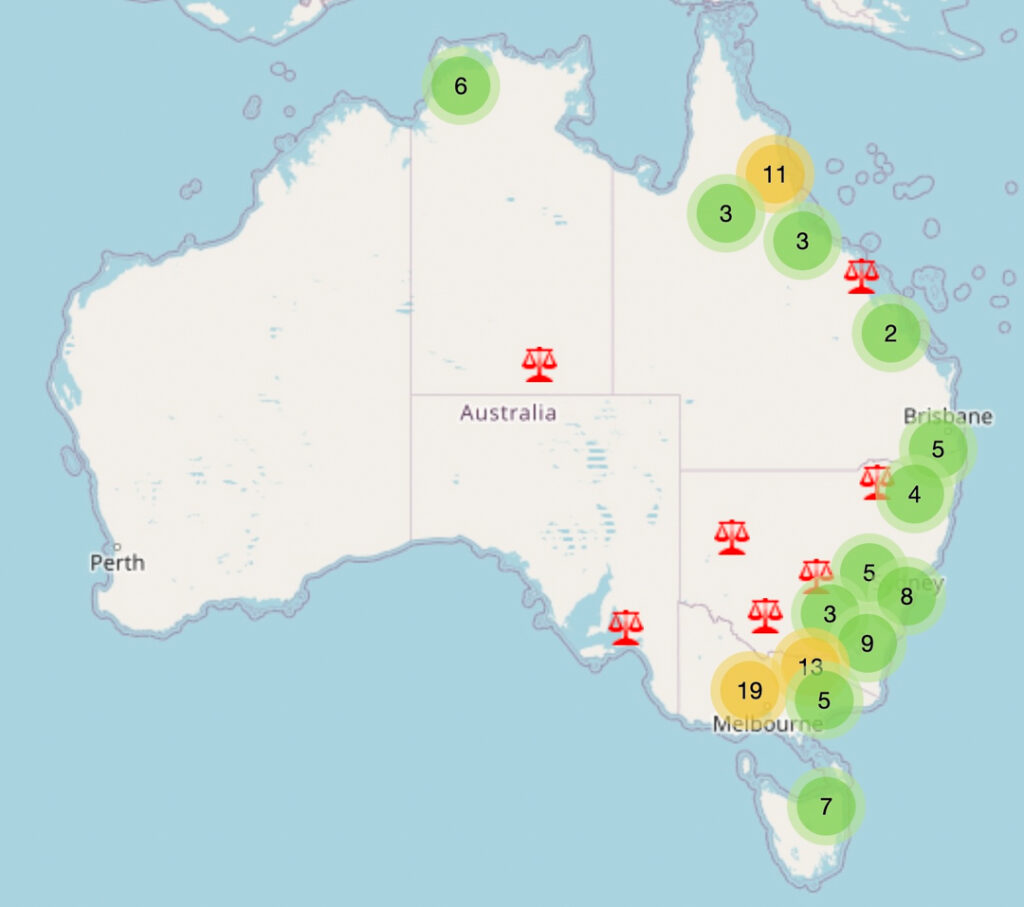

Today, only a few of these nineteenth-century Joss Houses remain, with the See Yup Temple in Melbourne and the Holy Triad Temple in Brisbane standing out as notable examples. Both continue to function as active places of worship. In contrast, the temples in Bendigo, Victoria, and Atherton, Far North Queensland, have been preserved as museums, offering a glimpse into the past. Surviving temples include the Holy Triad, Brisbane (1886), the Si Yi Temple in Glebe, Sydney (built in 1904) and the Yiu Ming Temple in Alexandria, Sydney (constructed in 1920). Some temples were rebuilt, such as the Lit Sing Gong Temple and Innisfail, which date back to 1940. More recent additions to the Chinese temple landscape include the Wong Tai Zin and Kwan Yin Temple in Sydney’s Summer Hill and the Nan Tien Temple, Wollongong.

The Cultural Heartbeat: Artifacts from Foshan

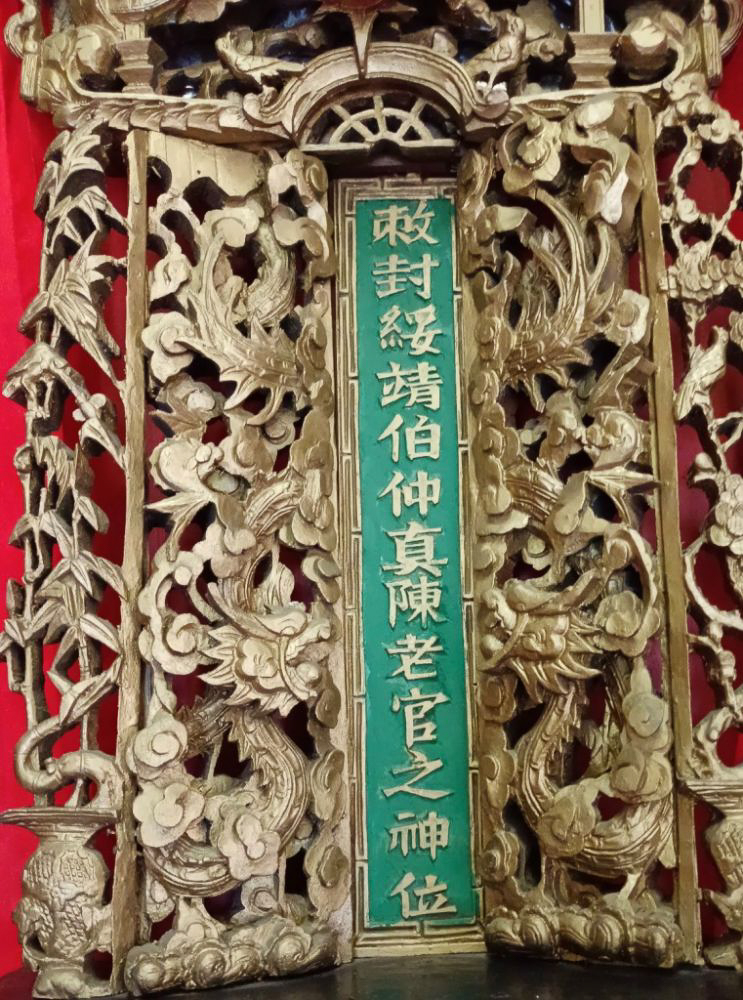

The Joss Houses were more than just places of worship; they were community hubs, especially during festivals like the Lunar New Year. Wealthy members of the community often donated money to import religious artifacts from China. Foshan, a city in the Pearl River Delta, was a major centre for the production of temple items. The Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery in Launceston now houses one of the most spectacular collections of these artifacts. This collection is made up of pieces from a number of Joss Houses that once dotted the tin mining villages of North-East Tasmania. In a remarkably advanced move for the times, these items were donated in the 1930s by the Tasmanian Chinese community and they remain today a working temple within the museum.

Altar and temple set up in Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery, Launceston. Photo courtesy of author.

A Multifunctional Space

Unlike Christian churches, Joss Houses served multiple community purposes. Much to the shock of European observers, they could be used not only for worship, but gambling, accommodation and even opium smoking. A custodian typically lived at the temple, earning a living from tips or fees. Temples truly came alive during festivals, especially the Lunar New Year, when it became the focal point of community celebrations, with feasting and fireworks that often attracted non-Chinese locals.

Despite their long-standing in so many communities, in the first half of the twentieth century, most temples were gradually allowed to fall into decay as their Chinese community dwindled. Some were destroyed by bushfires, arson, or simply abandoned. However, thanks to local plundering and spasmodic preservation efforts, a range of fascinating and often beautiful items have survived. These artifacts serve as lasting reminders of what were once common features of the Australian landscape.

Bells and Beyond: Surviving Artifacts

Among the surviving temple artifacts, iron bells stand out as particularly resilient. With their Foshan manufacturers’ marks and dates cast into them, these bells provide valuable historical information. However, perhaps only ten such bells are accounted for today, suggesting that not all temples, especially the earlier ones on the Victorian goldfields, had bells. With seven of the ten known surviving temple bells to be found in Queensland, where temples were constructed slightly later, it can perhaps be conjectured that bells were part of an evolving pattern of temple paraphernalia.

While bells are impressive, most surviving temple artifacts are elements of their internal decoration, such as altars, character boards, and statues of the gods. The statues, often small and modestly crafted, were sometimes represented by posters, which have not survived. The statue of Kwan Yin in Launceston appears to be one of the more elaborate examples. Most of these elements were imported while the building itself was, of course, locally made, including the carving of stone column supports in the case of the Croydon Temple in Far North Queensland.

Character boards, another significant feature of Joss Houses, often displayed the temple’s name or religious quotations. These boards were typically large, with some containing the names of donors. The calligraphy on these boards was often created from the writing of someone of note, adding to their cultural significance. More research is needed to determine whether other examples of such calligraphy scattered across Australia were the work of famous Chinese individuals.

The most elaborate and finely produced pieces were the altars, adorned with carved figures depicting stories from Chinese history and mythology. These altars featured animals, gods, and plants, all imbued with symbolic meaning. One of the best-preserved altars is in Rockhampton, where an alternative presentation of the god is also seen, with the deity’s name written on a tablet above the altar rather than depicted as a statue.

The Chinese temples of Australia, once vibrant centres of community life, have largely disappeared. Nevertheless, numerous artifacts they housed have survived in many localities to provide us with a window into the past. These enduring items, from bells and character boards to altars and statues, reflect the rich cultural heritage of the Chinese communities that helped shape Australia in so many still as-yet unrecognised ways. As we continue to uncover and preserve these pieces, we gain a deeper understanding of the historical and cultural significance of these temples and the communities that supported them.

Further Reading

Gordon Grimwade, Worshiping the North: Early Chinese Temples in Mainland Tropical Australia, International Journal of Historical Archaeology, October, 2024.

Benjamin Penny, “Taking Away Joss: Chinese Religion and the Wesleyan Mission in Castlemaine, 1868,” Humanities Research, Vol. XII No 1, 2005, pp. 107-117.

Note

The term “Joss House” was commonly used in trade English, derived from the Portuguese word Deus. It was a neutral descriptor, unlike “Chinaman,” and is still a useful search term for historical research.

About Michael Williams

Michael Williams is an Adjunct Professor at Western Sydney University and a graduate of Hong Kong University. Michael is a scholar of Chinese-Australian history and a founding member of the Chinese-Australian Historical Society. He is the author of Returning Home with Glory (HKU Press, 2018), which traces the history of peoples from south China’s Pearl River Delta around the Pacific Ports of Sydney, Hawaii and San Francisco and Australia’s Dictation Test: The test it was a Crime to Fail (Brill, 2021). Michael’s most recent publication is a history of the Robe goldfield walkers entitled Every requisite for a campaign upon the gold-fields (ChidestudyPress, 2024). His website Chinese Australian History in 88 Objects was shortlisted for the 2022 Premiers Digital History Prize. Michael is currently project manager of the federally funded Scattered Legacy project, a national database of Chinese Australian history.

Michael Williams is an Adjunct Professor at Western Sydney University and a graduate of Hong Kong University. Michael is a scholar of Chinese-Australian history and a founding member of the Chinese-Australian Historical Society. He is the author of Returning Home with Glory (HKU Press, 2018), which traces the history of peoples from south China’s Pearl River Delta around the Pacific Ports of Sydney, Hawaii and San Francisco and Australia’s Dictation Test: The test it was a Crime to Fail (Brill, 2021). Michael’s most recent publication is a history of the Robe goldfield walkers entitled Every requisite for a campaign upon the gold-fields (ChidestudyPress, 2024). His website Chinese Australian History in 88 Objects was shortlisted for the 2022 Premiers Digital History Prize. Michael is currently project manager of the federally funded Scattered Legacy project, a national database of Chinese Australian history.