- Judith Crispin, Anthony over Henry’s Country, where the possum-men armies fought and were buried by pythons, beside speartrees, on the edge of a dry waterhole, 2019, Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verre, chemigram. Roadkill brush tail possum, fur painted with copper chloride, magnesium sulphate, gold chloride, developers and salt, on fibre paper, 28 hours under Perspex marked with crayons, 100cm x 61cm

- Judith Crispin, Honeyeaters know there is a special place after death for birds who have the courage to leave this world singing. Those are the bird warriors. Not fighters, but the ones who look death in the eye and sing, 2018, Lumachrome glass print. Honeyeater fallen to old age, household chemicals, mud and maggots on fibre paper. Exposed 31 hours under Perspex in spring light, 44.4cm x 63.5cm

- Judith Crispin, Mother lost to trucks, it was cold, and the night raining stars. Henry left the highway, following songlines across the great dividing range, to the sky country of kangaroos, 2019, Lumachrome glass print, chemigram. Frozen newborn joey on fibre paper, 36 hours in very cold conditions, mist and winter light, 75.0cm x 58.5cm

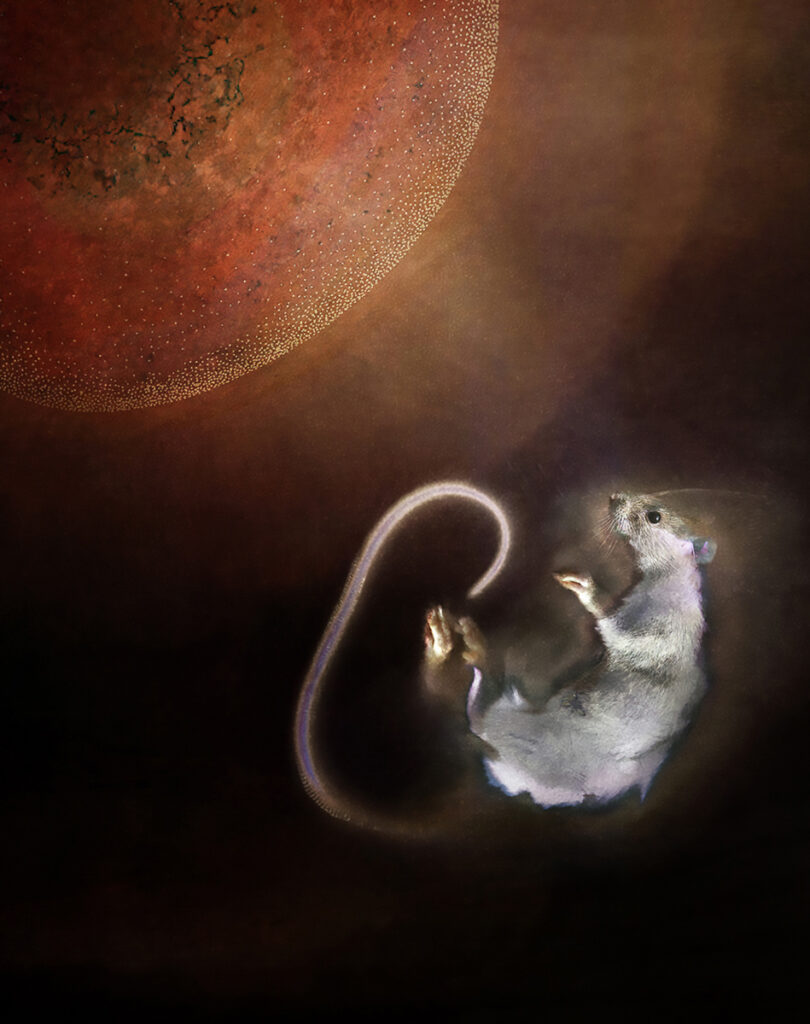

- Judith Crispin, In dawn frost, Herb surrendered his body to tangled vines and lifted into the sun, 2019, Lumachrome glass print, chemigram, cliché-verre. Rat found in the ivy of Greer’s window, copper chlorides and acid (electrified), tennis ball and coffee filters on fibre paper. Exposed 30 hours under marked Perspex in very cold conditions, 100cm x 79cm

- Judith Crispin, Ben sometimes felt he carried his artist girlfriend a lot, but she painted him stars while he slept, 2018, Lumachrome glass print, cliché verre. Double exposure. Roadkill magpie, seeds and ash on fibre paper. First exposure, 12 hours under marked glass in the back of a ute. Second exposure, 12 hours with additional seeds and dirt. Winter light, 44.4cm x 61.5cm

Alasdair Foster writes about the Lumachrome Glass Printing by Judith Crispin that renders decay in stillness.

Judith Crispin’s work is a remarkable synthesis of the timeless wisdom of Aboriginal tradition and a radically innovative approach to printmaking that spans photography and painting, pushing the limits of both to create pictures of intense poetic beauty. I first saw this work in China, in an exhibition presented by the spirited artist-curator Jeff Moorfoot. Since then I have come to understand how her images speak to people of many different cultures and in many parts of the world.

Judith Crispin was an adult before she discovered her Indigenous heritage. She then spent decades tracing her Bpangerang Grandfather’s people. While they are from an area in the northeast of Victoria, it was the Warlpiri people of the Tanami Desert who were to become her adoptive community.

“I owe the Warlpiri a great debt – they took me in as family, ‘growing me up’ when my own ancestry was unclear. However, I gradually came to understand that people like me will never have a genuine place in either white or black culture. We are ‘Nowhere People’, whose families concealed their Aboriginality to protect their children from forced removal and assimilation, practices which continued in Australia into the 1970s. Raised in white privilege, but never belonging to white culture, we tried, as adults, to reconnect with our missing history. And we learned, to our sorrow, that you can’t go back. Nobody can restore what was erased. We exist at the intersection of incompatible cultures and histories and, if we ever want to belong, we will have to create something entirely new to belong to.”

It is perhaps this perspective of unaffiliated outsider that garners her work such cosmopolitan appreciation. These images transcend notions of ancient versus modern to glimpse the continuity of the world across time, place and the dimension of the spiritual. They engage with profound grace the existential brevity that is the lot of all living things. These delicately nuanced allegories are created using the bodies of animals and birds killed on the road, combined with the ochres, seeds, twigs and leaves from the place that they are found. Those elements come together in a liminal process of creation in which the final result is a print that enshrines their ghostly trace: a visualisation of the transition from life and return to the maternal earth that stand as metaphors for the interconnection, healing and respect that rests at the heart of the Aboriginal concept of Country.

So, how are they made?

Lumachrome glass printing

The process that Judith Crispin has developed for the creation of these images she calls Lumachrome Glass Printing. It is a complex synthesis of at least five different photographic and craft-based processes: sun printing, cliché-verre, chemigram, an electro-chemical effect, and a harnessing of the products of bodily decay itself. All these techniques involve chemical and solar transformations of silver halide crystals embedded in the surface of the paper.

Sun Printing, now also known as Lumen printing, involves placing an object onto light-sensitive paper and exposing it to sunlight for an extended period. Depending on the type of photographic paper used, different colours form in the emulsion. While the images alone have a certain aesthetic, they are usually rather vague and the outcome difficult to control.

In order to create depth and detail in the background, the artist uses a process called cliché-verre, which combines drawing and photography. It was developed in the nineteenth century and popularised by artists such as Man Ray. In this technique, glass is laid over light-sensitive paper. This can then be coated with resin or paint, into which lines are scratched. When exposed to light, the photosensitive paper darkens below the areas that have been scratched away.

Further fine detail is added using the Chemigram process, which combines aspects of painting and photography. Invented by the Belgian artist Pierre Cordier in the 1950s, Chemigram involves the application of various substances on the surface of photographic paper, which resist the effects of developer or fixer, or both. In a sense, it is similar in principle to batik. Different chemicals act in different ways and Judith was lucky enough to receive advice on refinements in the chemistry from Monsieur Cordier himself. One significant refinement that she made is to paint the chemicals directly onto dead animal bodies before placing them on the paper, where they imprint the chemicals selectively onto the paper depending on the texture of their outer surfaces.

Branching patterns are created by running an electric current over a glass plate for forty-eight hours or more. Passing through metal salts and acids, the current creates dendritic crystals which can then be pressed directly onto the print.

The final technique works with the fundamental chemistry of organic decomposition. Judith calls this process cadaverchrome. Under glass, a decaying body releases gases and fluids. These substances produce colour in silver halide crystals. Using these fluids, she gradually builds up a background image, creating the impression of mountain ranges, cliffs, deserts, and sky.

Judith Crispin, Tamsin dreams of Froglady, her hairstring grazing the tops of rainforest trees, like an invitation, 2018, Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verre, chemigram. Fallen rocket frog, a lock of Tamsin’s hair and copper chloride solution (activated with battery terminals) on fibre paper. 17 hours in very humid conditions, 65cm x 35.5cm

Judith’s first Lumachrome print was of a tiger snake she found wound around a branch beside the road. She exposed the print by moonlight, on the night of the lunar eclipse. The cliché-verre element was simply glass fogged by dew.

“Later that month, I made a print from a frog. To my surprise, the resulting image clearly showed internal organs, including a womb and eggs. The human eye alone can’t see these things. Light reflects from the frog to my retina in a microsecond – everything we see is the result of fleeting observation. But in a lumen print, during an exposure of between twenty and fifty hours, light impregnates itself slowly in the silver halide crystals. The resulting print records much more than we can see with our eyes.”

Judith Crispin, Lily returns to Altair, the brightest of Aquila’s stars, wearing the body of a crow, 2019, Lumachrome glass print, cliché-verre. Roadkill crow, ochres and dandelion seeds on fibre paper. Exposed 32 hours in autumn light under brushed Perspex.

100cm x 79cm

Every image embodies its own narrative. Extended captions point to their allegorical nature, without over-describing what it is we see. There is an image of a crow which stands as a final portrait of a Warlpiri law-woman, hunter and custodian of bird dreamings. She had hunted food until she was ninety years old, she was covered from head to toe in ceremony scars, and sang to waterholes in the old Warlpiri language. She passed away in a nursing home, more than nine hundred kilometres from her ancestral lands. Frightened to die so far from Country, she asked Judith to take feathers to her ancestral lands after her passing, explaining that her spirit would follow those feathers back to Country.

“After she died, I dreamed of her in the body of a crow, her abdomen glittering with stars from the constellation Aquila, a sign of the bird. For weeks I searched for a crow. I knew it was my last chance to make a portrait of my friend. I made the constellation from dandelion seeds and paint, brushed the crow’s feathers with ochres from the bird’s own Country, and exposed the image over thirty-two hours.”

So, what is it that Judith Crispin seeks to communicate through these poetic visualisations of death and that which lies beyond?

“Warlpiri women have taught me new ways to understand death. In white culture, we rarely see someone after they’ve died. And when confronted by dead animals, most people feel disgust or indifference. We mourn the death of a celebrity, but we drive over the body of an owl on the freeway without hesitating. This dismissal of animal death as trivial, together with our strange refusal to bear witness to human death, has cut us off from every other lifeform on the planet. Making these Lumachrome Glass Prints is a way of restoring balance. Honouring a fallen bird or lizard seeks to overcome my enculturation: the hubris of elevating humans over all other species.”

These are remarkable images, rich and deep. Each is created through a kind of death ritual in which the artist honours the fallen creature with mysteries that draw from ancient lore and modern science, from human craft and natural decay, to speak of the one within the whole. For the artist herself, it is a profound and revealing experience, as she explains: “Watching a bird or animal decay over many hours, I see how the earth takes that dead body back into itself, like a fallen leaf or a shell … the gentleness of it.”

About Alasdair Foster

Dr Alasdair Foster is Professor of Culture in Community Wellbeing in the School of Public Health at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, and Adjunct Professor in the School of Art of RMIT University, Melbourne. He has twenty years’ experience heading national arts institutions in Europe and Australia and over 35 years of working in the public cultural sector. He was previously director of the Australia Centre for Photography (1998–2011) and founding director of Fotofeis, the international festival of photo-based art in Scotland (1991–1997). A writer, researcher and award-winning curator working in many regions of the world, he has previously been managing editor of Photofile magazine (1998–2009), president of the Contemporary Arts Organisations of Australia and Chairman of the Conference for European Photographers. He is currently Ambassador to the Asia-Pacific PhotoForum and publisher of Talking Pictures, interviews with photographers around the world. Visit talking-pictures.net.au/.

Comments

I can only repeat the words of Dr Alasdair Foster…………..these are remarkable pictures. Hauntingly beautiful, they capture your inquisitive mind and hold it hostage, quietly. I keep returning to enquire further, peacefully.