Kevin Murray explores the studio of an Indonesian artist, filled with shadows of history, culture, craft and dreams.

“Music and mythology bring man face to face with potential objects of which only the shadows are actualised, with conscious approximations (a musical score and a myth cannot be more) of inevitably unconscious truths, which follow from them.”

Levi-Strauss Naked Man (1971)

Given lockdown restrictions, my visit to Jumaadi’s studio is a dream-like Zoom experience. Jumaadi invites me into his palace of wonders, but I can’t touch or smell anything. I glimpse his kitchen, where he often prepares a tasty gado gado salad and sambal prawns for guests. A guitar lies against a wall, promising a convivial singalong.

Captive to his mobile camera, I look at the work he is making for a public commission: papercut stencils of people on trees, to be hung under a bridge. It’s a sign that his work is beginning to take hold in Australia, as it begins to feature in major public sites.

Next are his paintings, which are a key part of his studio life: “I like to work from dark to light. They are like playing music on a pentatonic scale. The five notes become a language.” I am thinking of gamelan music made visual, when sound becomes colour.

We then move back into a shadowy past. Jumaadi shows me an ikat that he purchased from Sumba. Textiles were key to political power on the island. Traditionally, rulers were bestowed with the patola ratu, “cloth of kings”. The Dutch cleverly used this practice themselves to build local alliances. Jumaadi’s hinggi ikat depicts a “skull tree”, which refers back to the traditions of headhunting. While this practice was seen as barbaric by the Dutch, Jumaadi reflects on an episode in nearby Banda island in 1625 when the Dutch ruler Jan Pieterszoon Coen massacred the local inhabitants, ordering his Japanese soldiers to behead the locals with their samurai swords. It was all for nutmeg, the nutraceutical drug of choice of the day.

Looking at Jumaadi’s wayang works, I can understand why this ikat has drawn his attention. There is something quite disembodied about his scenes. Jumaadi’s Mosman Art Gallery exhibition early 2020, My Love is an Island Far Away, featured surreal versions of the tree of life.

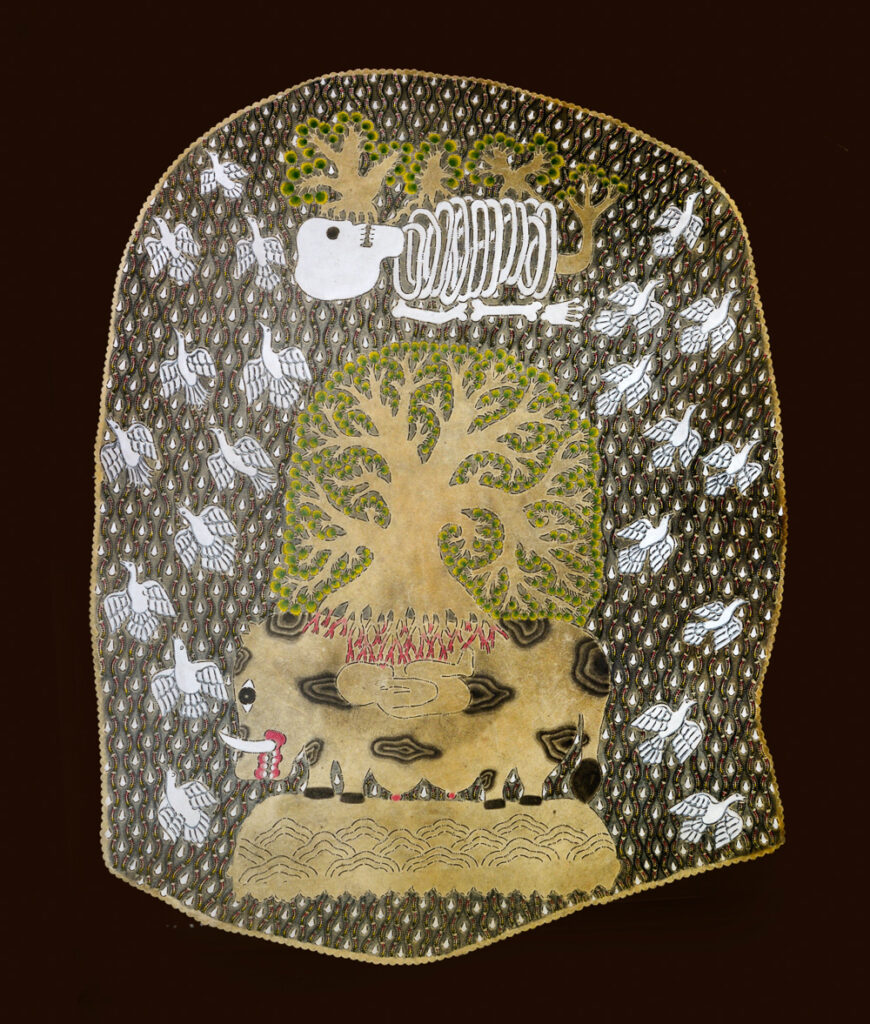

- Jumaadi, Tree of Foetus, 2019 – 2020, buffalo hide, 70 x 80 cm

A suite of works was based on the gunungan (mountain), which is a form used in Wayang Kulit to signify a change of scenes. It usually combines the three worlds: the world of gods above, natural life in the middle, and the realm of demons below. This is often linked together with the tree of life form.

One artwork, in particular, caught my imagination. Bags hanging from branches, on which were foetuses outlined by dendritic roots. The tree itself was clothed in feminine underwear, which juxtaposed quite strikingly with the skull at its base. It’s a disturbing play of life and death.

When I ask Jumaadi about this in a later phone call, he tells me that the feminine garment is meant to convey a sense of sacred—not to be touched. The idea of the skull comes from a visit to a temple Candi Surowono in Pare, Kediri, East Java. Skull motifs at the base reflect a sense of mutuality between life and death in Javanese religion. They express the concept of sangkan paraning dumadi, “remembering the origin and destination of life.”

Life casts its shadow. Wayang (Indonesian for “shadow”) is a Javanese puppet theatre that parallels Plato’s allegory of the cave, where mortals witness the actions of figures controlled by the almighty Jagatkāraṇa (the mover of the world). Originally from southern India, this art form has traditionally conveyed the epic narratives of Mahabharata and Ramayana. The Wayang Kulit performance will often last from dusk to dawn. I remember lying on the lawn during a long balmy night many Adelaide Festival’s ago, marvelling at the capacity of performers to sustain a story until sunrise.

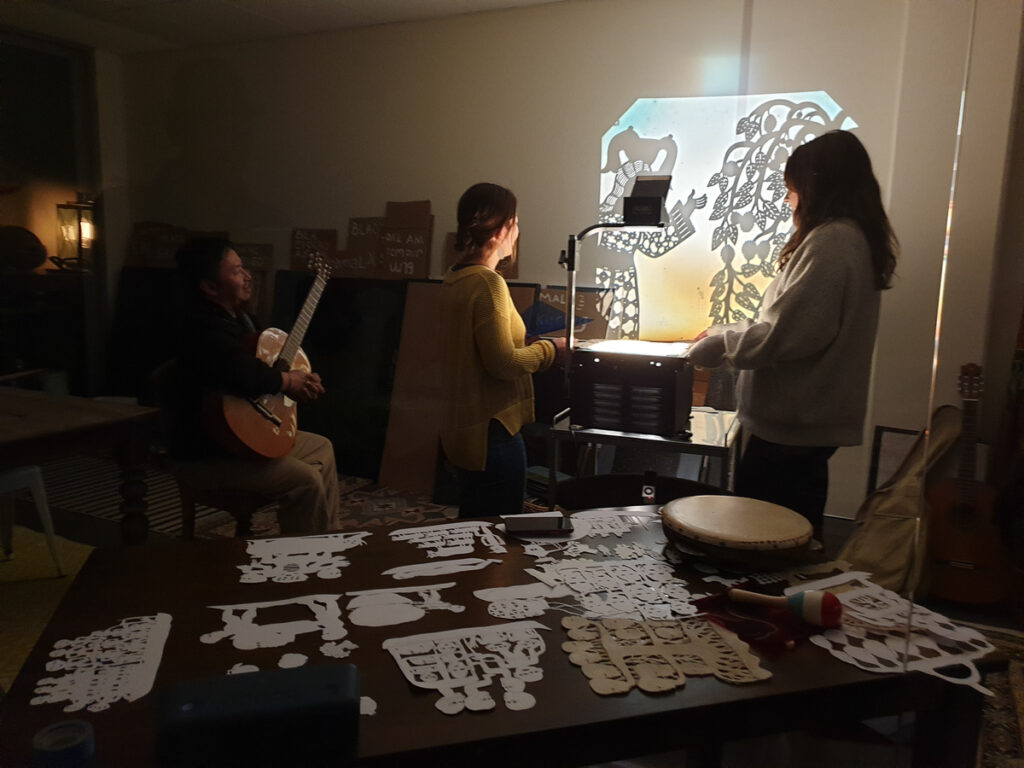

Jumaadi’s buffalo hide puppets are made in Imogiri, a town south of Yogyakarta that he visits regularly (or used to). He draws then cuts out the scene on paper, which is traced onto buffalo hide. The hide is cut by four artisans in the studio, then painted together with Jumaadi.

Jumaadi’s creative use of wayang contrasts with the traditional approach. I recently “attended” a talk by a wayang maker hosted by Meet the Makers – Indonesia. Pak Sagio in Yogyakarta spoke of proudly continuing this 1,000-year-old tradition thanks to his committed son. He did emphasise how the appearance of the puppets has changed as different techniques are used. But when asked him if there was any change in the actual stories told, he was quite adamant: “The appearances might change, but the stories don’t.”

It’s an important counterpoint to the work of Jumaadi. As an Australian-Indonesian artist, Jumaadi bridges the studio and workshop. He draws on the traditional skills of wayang kulit but adapts them to flow of his artistic imagination, fed by the shadows of Indonesian history.

This is not to presume that unchanging narratives are a mindless following of tradition. Like an heirloom, an unbroken story becomes a link across generations, giving greater purpose to the present generation, with compound interest. But a Western settler-colonial nation like Australia offers a complimentary space for re-invention—pembaharu.