- Noorjehan Bilgrami

- Process work for Noorjehan Bilgrami work

- Sadia Salim

- Process work of Sadia Salim

- Wardah Bukhari

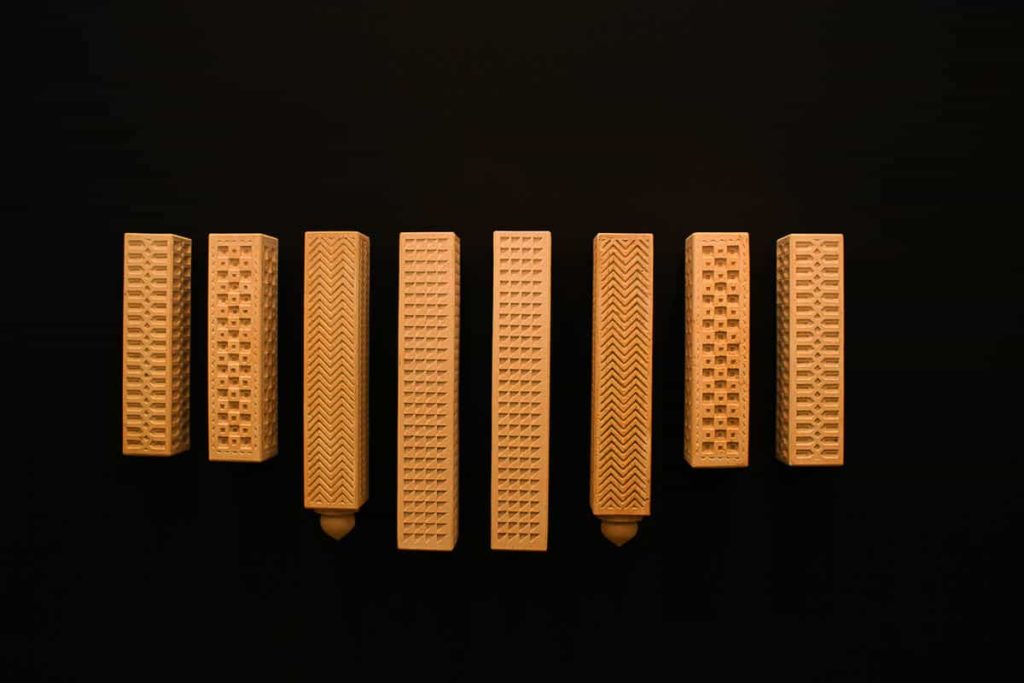

- Tahir Malik

- Tahir Malik

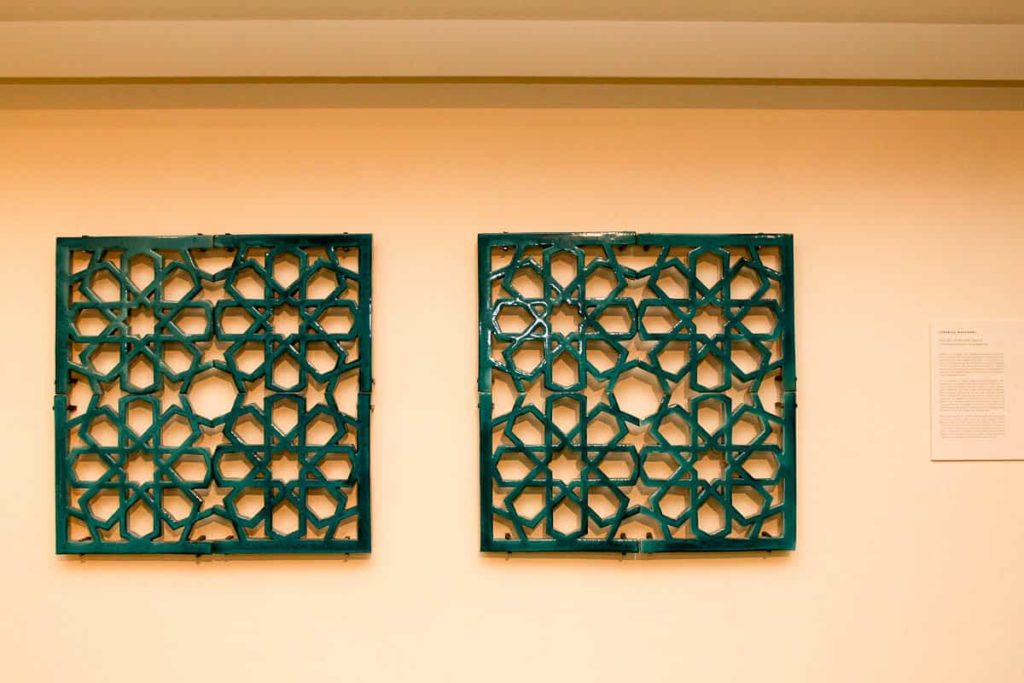

- Arshad Faruqui

MANZIL: Exhibition of Traditional Crafts and Contemporary Adaptations was exhibited at Koel Gallery, Karachi. Zarmeene Shah briefly introduces this important project for craft-design collaboration in Pakistan:

With a view towards the safeguarding of Pakistan’s rich cultural heritage as manifested through its indigenous craft traditions, the exhibition Manzil presents 13 collaborations between designers and craftspeople who engage in processes of continuance, revival, adaptation and interpretation in creating contemporary objects that find themselves rooted in a diversity of traditional craft practices from the region.

Today, globalisation and industrialisation pose the greatest threat to the continuation of this most tangible form of our intangible cultural heritage. In order to ensure that these myriad forms of traditional craftsmanship are not lost, the focus must be less on the specific objects produced and rather on how these age-old forms of knowledge and skill, passed down through generations of master artisans, can be not only preserved but also made relevant to the globalised demands of a contemporary world. Thus through collaborations with designers and the showcasing of these methodologies and bodies of knowledge in Pakistan’s urban centres, Manzil attempts to (re)connect new populations and audiences with these traditional crafts, emphasising their cultural worth and value, and the critical importance of their continuation.

This exhibition is the inaugural initiative of the Pakistan Crafts Council, in collaboration with the Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund.

To learn the story behind this, we asked co-curator Noorjehan Bilgrami.

✿ What does Manzil mean and why was it chosen as the title of the exhibition?

Manzil, has several meanings depending on how it is used in a sentence, in what context it is used. Most commonly it is referred to as the “destination”, “house”, and stage.

In Plattis Dictionary, Manzil’s meaning is elaborated It can mean as a noun – “of place”, “a place for alighting”, “a place for accommodation of travellers”, a “caravanserai”, “an inn”, “a hotel”, “lodging”, “dwelling”, “mansion”, “habitation’: “a mansion of the moon”, “story or floor” (of a house), “a day’s journey”, “a stage” ( in travelling, or in the divine life), “goal”, “boundary”, “end”, “limit”, manzil ba manzil—”from stage to stage”.

It can have Sufi connotations, of the stages to reach the Divine!

It seemed very appropriate to keep Manzil as the title, as the underlying theme was to trace traditional crafts of Pakistan from its origin to the present and look at it as a functional, contemporary response.

✿ What was the goal and rationale of Manzil?

The aim of the exhibition Manzil was to document and revitalise the existing but fast disappearing crafts of Pakistan.

The goal was to inject a fresh approach to some crafts by designers, architects and artists. Participating artists, architects and designers were to select one traditional craft, work in conjunction with a Master Craftsperson and design a functional product, which is easily reproducible, using the traditional method and technique.

Each exhibit consisted of the following four components:

- An authentic specimen of the selected craft as made and used traditionally

- A functional product

- Visual documentation (photographs or video) of the process including name of the craftsperson partnering in the product making

- A brief but well researched write up

✿ Were there particular conditions attached to the collaboration, such as who would own the designs that resulted?

There were no conditions attached to the collaboration between the designers and the master craft-persons.

The exercise was initiated and led by the designer (artist/architect). The design development was an amalgamation of the designer’s concept and the expert skills and technique application of the Ustad (master craft-person).

The idea was to share and work together to restore the design sensibilities and the quality of workmanship that has gradually eroded. During the process, craft-persons became more aware of their own potential and knowledge.

The design evolves from the common repertoire of that particular craft and as such is difficult for anyone to own. Consumers/clients play the third role by accepting the end product. Their response shapes the demand.

✿ Can you provide an example of a collaboration that you think worked very well?

An exciting innovation happened when a designer, Sadiqa Tayebaly in Karachi, worked with Iqbal, a dabgar (craftsman who makes camel-skin lamp shades) in Multan. They experimented by taking a mould impression of the intricately carved jaali of an antique wooden window. The result was amazing. That experiment led to work by another craftsman, who chiselled patterns on a stone surface to work on the surface of the camel skin etching stone designs. There was a wonderful exchange of ideas between the designer and the master craftsmen.

Note from Sadiqa Tayebaly:

For over a hundred years the dabgar has been moulding basic geometric shapes in camel skin and no attempt has been made towards a change. These lamps have been famous for the Naqashi and the work of the dabgar has never been highlighted.

The idea of my intervention was to work with the dabgar and create two-dimensional designs so the beauty of the skin itself is highlighted giving the dabgar a chance to be creative with his work and be able to create products independently.

Initially, the dabgar refused to experiment with the given task, but he eventually took the plunge hesitantly. He was quite sure his hard work would be fruitless and discouraged me at every step.

The success of this intervention was clearly visible in his voice when I first spoke to him upon completion. We are quite hopeful to have opened new avenues in this material and process.

This design is inspired by an old Chinioti carved window. We have worked at creating a new, second dimension, using the traditional skill, materials, tools and process, so the artisan can explore new markets and revive lapsed markets without losing the authenticity of the craft.

✿ Were there any unexpected challenges from the Manzil project? Did you learn anything new from the process?

Coordinating with the designers and their respective craftspeople became a challenge in some cases and I cannot say that it worked seamlessly. Through this exercise, I am hoping a more cohesive method for design development and its sustainability will emerge. Accessibility was an issue in some of the remote areas and problems were more difficult to resolve. The exchange between the designer and master craftsmen at close proximity is more productive and quicker. Documentation of the process was also varied and did not easily adhere to the suggested format. The main learning was to develop patience and wait for the gradual exchange and assimilation of ideas. We hope the next exhibition would develop the concept and take it a step further.

Author

Noorjehan Bilgrami is a visual artist, textile designer, researcher and educationist. Founder member of the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, she was its first Executive Director, 1990–95, and former Chairperson, Board of Governors. Her atelier, Koel, pioneered the revival of hand-block printed, handloom and natural dyed fabrics in Pakistan. The Koel Gallery, established in 2009, is a vibrant platform for emerging and established artists. Noorjehan’s publication, Sindh jo Ajrak and film, Sun, Fire, River, Ajrak – Cloth from the Soil of Sindh, document the traditional textile. She authored Craft Traditions of Pakistan and Born of Fire, a profile of Pakistan’s renowned ceramist Salahuddin Mian; a documentary film, Yeh Kiya? and curated a Retrospective Exhibition on the artist at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture.

Noorjehan Bilgrami is a visual artist, textile designer, researcher and educationist. Founder member of the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, she was its first Executive Director, 1990–95, and former Chairperson, Board of Governors. Her atelier, Koel, pioneered the revival of hand-block printed, handloom and natural dyed fabrics in Pakistan. The Koel Gallery, established in 2009, is a vibrant platform for emerging and established artists. Noorjehan’s publication, Sindh jo Ajrak and film, Sun, Fire, River, Ajrak – Cloth from the Soil of Sindh, document the traditional textile. She authored Craft Traditions of Pakistan and Born of Fire, a profile of Pakistan’s renowned ceramist Salahuddin Mian; a documentary film, Yeh Kiya? and curated a Retrospective Exhibition on the artist at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture.