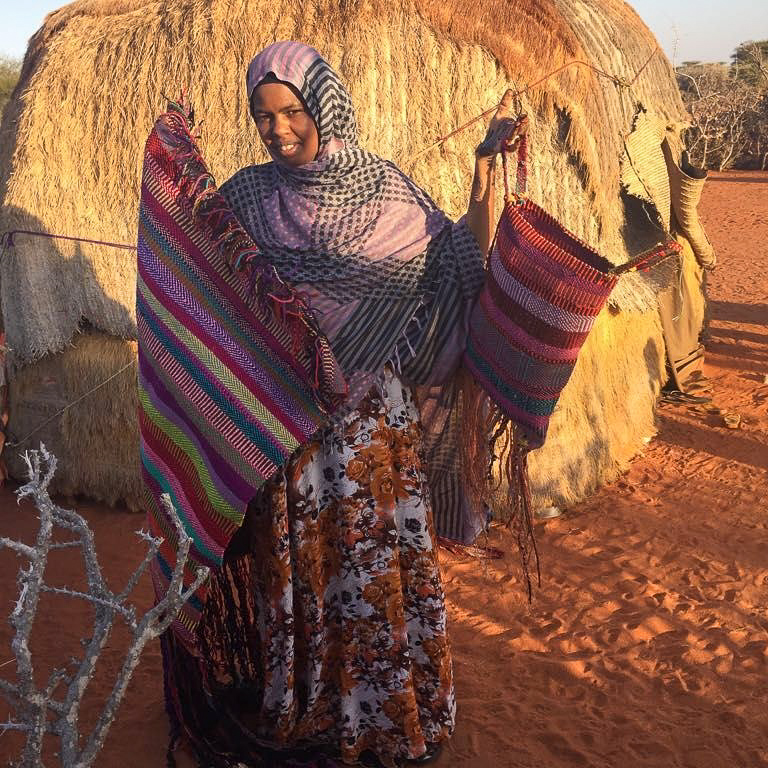

Muhubo Suleiman in her aqal.

In her Melbourne flat, Muhubo Suleiman has re-created the aqal, thatched hut, her childhood home in Somalia.

On a cold autumn afternoon, I walk down to the entrance of the Carlton housing commission flats. Council officers in hi-viz are clearing the car park in front of the Stalinist grey high-rise buildings. An elderly African man guides me into the lift, using his key to press the button, for these are the pandemic days. I emerge onto the ninth floor disoriented: the apartment numbers don’t match the floors. I go downstairs and look down a long corridor to find a woman draped in gleaming textiles beckoning me.

Muhubo Suleiman in Somalia

Muhubo Suleiman was born in the village of Guldugup, on the border with Ethiopia. Her family were nomads who tended cattle. She was already known for her hand skills and would make her own buttons. Today she remembers particularly the thatched hut she grew up in, known as aqal.

When she was 13 years old, the family was forced to leave for the town of Galkayo. At that time, there was a civil war and the countryside was overrun by refugees from the city. Life took a downward turn. They once had 100 cows and 500 sheep. Today her mother only has 30 sheep.

Muhubo’s sister fled to Egypt and found asylum in Australia. Muhuho spent time in Egypt too, when she gave birth to her daughter and learnt Arabic. Her sister then sponsored her to come to Australia.

Muhubo was quite surprised by her first encounter in Australia. “I arrived at Melbourne airport with no English. I had to wait for two hours to make the connection for Sydney. I was hungry and tired and so I fainted while still holding my daughter. I woke up in a different part of the airport with a man who found me some food and how to catch the plane to Sydney.” She wasn’t expecting this kind of care from a stranger.

The distrust of the world she inherited from her past persisted in Australia. “In Sydney, I had to catch a tram to Paramatta. I didn’t know how to use the pram and it got stuck on the gap between the tram and the road. There were ticket inspectors on board and I panicked thinking they wanted to take my daughter.”

Muhubo eventually settled into the inner-suburb of Carlton in Melbourne. She still hasn’t seen a farm yet. “When I feel lonely, I look at the trees and walk. I cut some grass and weave.” She started weaving baskets five years ago and is driven to re-locate her past life in this new world. She even re-created an aqal inside her flat, as well as miniature versions that function as dollhouses.

She demonstrates the aqal in careful detail. It is covered by many different kinds of weaving, which make it a kind of gallery, though an inverted one. The front of the textile faces inwards, so only one or two people can see it in true glory. It is a smaller version of what she originally grew up in. Muhubo has also re-created a number of Somali objects such as walool bamboo stick weaving and waymba decorations.

She was supported in her development by the Social Studio and took a residency at the Australian Tapestry Workshop. Adriane Haywood, the Exhibitions Coordinator at the Australia Tapestry Workshop, saw Suleiman’s work as a relief from a monotone Western city:

No longer a utilitarian necessity for Muhubo, Somali finger weaving can be used to connect communities by bringing together young and old to work collaboratively on recreations of these nomadic huts woven using Australian native grasses and colourful yarn. When Muhubo first told me her life story, from a nomadic childhood in Somalia to living in inner-city Carlton, I understood the significance of this weaving practice as a connection to her homeland but also a way to evoke the bright colours and textures of her upbringing that were missing from a grey, dark Melbourne winter. In hearing how far Muhubo had come I was humbled by her perseverance to navigate the complications of ‘home’ for diaspora and the courage to communicate this to the world.

Muhubo Suleiman revealing the inner designs of the aqal.

Muhobo has been assisted greatly by the local social enterprise, Social Studio, which has been providing refugees with practical skills in fashion and catering. Her teacher at Social Studio, Mariam Mousslimani, reflects on her contribution:

Muhubo is a treasured student at The Social Studio. With her kindness and generosity, she continuously educates us about the significance of hand weaving and its historical importance. Muhubo’s handcraft is intricate, functional and beautiful, using wool yarns and many other organic materials like straw, grass and wood. Muhubo has a small weaving business where she hosts workshops in partnership with organisations like The Social Studio and the City of Melbourne and offers a range of hand made ornaments and handbags. Her most recent exhibition in collaboration with the State Library @library_vic and VAMFF @VAMFF featured a traditional Somalian hand draped garment infused with her traditional hand weaving skills. This garment represents strength and power that highlights a historical moment for women of Somali cultures.

Muhubo Suleiman with the aqal doll’s house.

Muhubo has plenty of initiative herself. Her own business is called Qaymi, which means a “master” who is capable of making new things. Her dream is to promote “multicultural” weaving in a museum that tells the story of her Somali culture. She has been involved in many workshops, though future bookings were cancelled due to coronavirus.

One of her three children, a daughter studying law, joins us for a cup of Somali cardamom coffee in her living room. I ask Muhubo about her own mother back in Somalia. Is she sad to have lost a daughter? Fortunately, her mother has a total of eight daughters (two each in USA, Canada, Australia and Somalia). They dream one day to have a reunion back in the homeland. Life in the Somali countryside has not changed for her mother. She is free to roam wherever she pleases. But she worries about Muhubo, confined on the other side of the world.

Muhubo is hardly constrained. She has her home within a home. On her last trip back to Somalia, Muhuho was saddened to see that the aqals had disappeared, replaced by mass-manufactured tents. She is keeping a lost tradition alive in her humble Melbourne flat.

As I walk back up to the tram, I look back on the Carlton flats. I feel an unusual twinge of pride to think that my city can provide someone like Muhubo with a place to start again, on the other side of the world. I wonder at the other possible colourful worlds within worlds contained within this edifice. One day, will they have goats again?

Comments

Thanks for giving us this inspiring encounter with Muhubo, Kevin.

Muhobo, your work is so beautiful.

I love the colours and designs, thank you for sharing.

Keep safe, and keep weaving.

Moving story and the connecting strength of making. thanks.