- The road to Tjukurla, the northernmost homeland community in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. Photo: Glenn Iseger-Pilkington, 2017

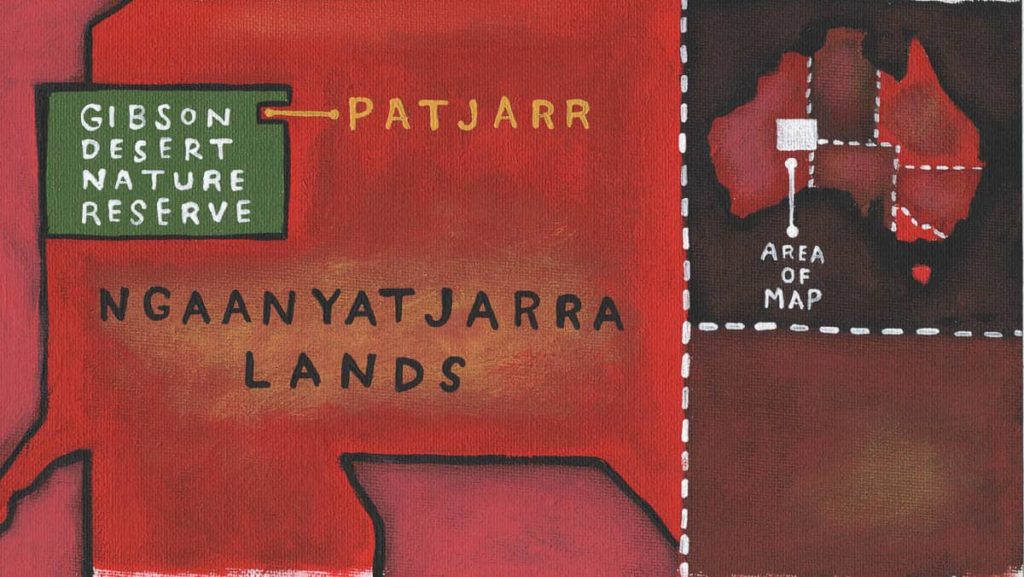

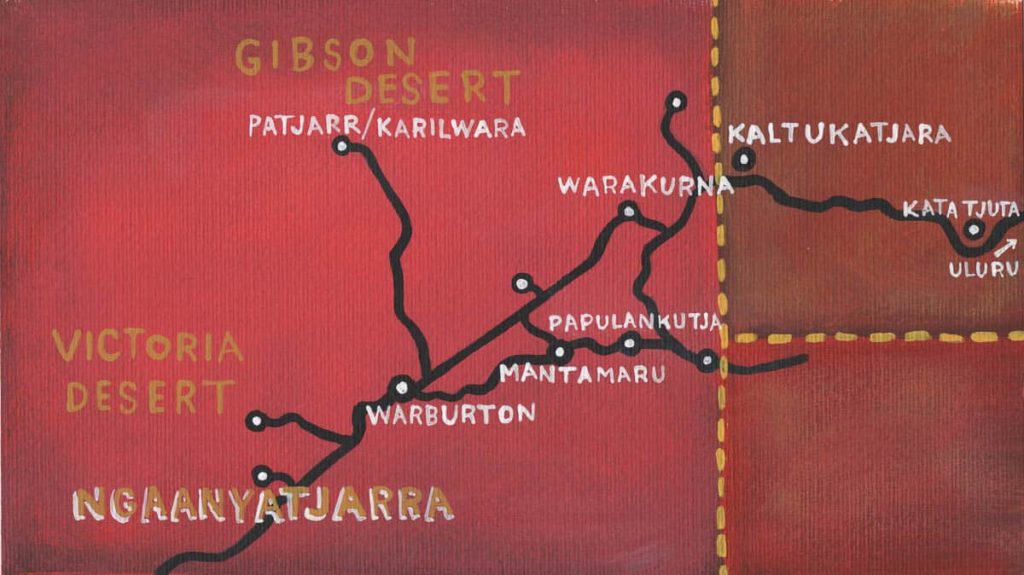

- Map of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. Artist Violet Cooper

- Map of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. Artist Violet Cooper

The smell of coffee fills the room, afternoon light is pouring in through the window. A small Nyarapayi Giles painting stares back at me from behind my computer monitor, a painting of her home, of Karku. I am sitting in my home office, beginning to write an essay about what ‘home’ means for Ngaanyatjarra people. My home, one of many I’ve had through the course of my life, is just a stone’s throw from Fremantle in Western Australia. On almost every wall in my home you will find pictorial and cultural representations of other peoples’ homes, from North-East Arnhem Land, to the Western Desert to the South West. The artists who created each work, are custodians of their Country, they care for and belong to the places they paint, sculpt, draw and photograph.

Lately, I’ve found myself reflecting on how close our home is to Wadjemup (Rottnest Island), where Captain Stirling first anchored his ship, where all the changes started, well, in a more recent chapter of the story of this place. I’ve also been thinking about all of the places I’ve lived, my connections to these places and how they are connected to each other. Right now, it is just a few days out from Survival Day/ Invasion Day / Australia day, or, simply, January 26. Every radio show, every TV program, every conversation I hear seems to include a dialogue around changing the date, around whether it makes any difference, the usual rhetoric from government representatives, yet there seems to be a little more support this year, a little more compassion. The commentary, particularly in the media, seems to be missing something quintessential: the voices of Indigenous people.

January 26th is a date of great contestation here in Australia, and rightly so. This contestation emerges from how people relate to their home, Australia. For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, this is a day of great sadness. For some Australians, it is a day of celebrating Australian culture, their experiences as ‘Australians’ and their pride for our nation. It’s a day for heading down to the fireworks on the South Perth foreshore. There is of course another group of people, who see this day as a celebration of colonisation, of the great achievements of empire. The problem here is that January 26 commemorates a colonial narrative, the invasion of Australia and the great atrocity inflicted upon First Australians soon after, including the imprisonment, massacre and torture of entire societies, the rape of women, the introduction of disease, and the dispossession of land and language, just to name a few. Beyond these are of course the legacies of this invasion, the continued and systematic removal of children, alarming rates of Indigenous deaths in custody and the intergenerational trauma passed down across generations, which manifests itself in a multitude of ways.

The more I think about it, at the centre of this are our relationships to our “homes”, to our land, to our rightful place in the world. Often, we think of home as being a singular place, perhaps a particular property or a house. Beyond that, these concepts of home extend to a town, a city, a state and a nation. This belonging we feel is central to our sense of self, and defines who we are. So, in the instance that our homes, cities, states and nations were forged through the colonisation of an existing society and their land, or in an Australian context, an entire continent, it is inevitable that our homes will be the subject of great debate. If our homes, suburbs, towns, cities and states sit on the stolen lands of Indigenous peoples, shouldn’t this be a part of a reflexive national discourse, a part of our truth-telling as a Nation that considers itself as a leader within the developed world? Shouldn’t our collective awareness, and social consciousness, as inhabitants of an imposed colonial nation-state be one that considers this dark history, and pre-colonial society as a part of its identity? The erasure of truth and history, and the silencing of voices, continue to pervade this nation, while our communities seem to take solemn steps into an uncertain future.

This isn’t an essay that will interrogate the discourse around Australia Day or changing the date, as this particular debate is not central to understanding the homes of Ngaanyatjarra people of the Western Desert, a vast expanse of desert Country that sprawls across Western Australia, the Northern Territory and South Australia. Rather, this text acts as a reference point by which to understand the reasons why so many Indigenous peoples continue to fight for their land, for their homes, which always were, and always will be, Aboriginal land. Ngaanyatjarra people, unlike so many communities across southern coastal Australia, whose lands were invaded during the earliest periods of the colonial adventure, have retained their language and their cultural, social and political structures. Although white people ventured into the interior of Western Australia in the late 1800s, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the Warburton Mission was set up. Mission times, of course, had a great impact on Ngaanyatjarra people. However, the return to homelands movement, which for Ngaanyatjarra was mostly self-initiated, saw a revitalisation of culture, knowledge and a pure determination to never be moved again, to always remain on Country.

Ngaanyatjarra people live in the Western Desert, on the western side of the tri-state border (Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia) and possess an expansive sense of what home means. Their word for home is ngurra. Ngurra speaks to place, history (both recent and ancient), the creation of landscape, cultural knowledge held in the minds and hearts of people and most importantly, it speaks to a web of interconnectivity between people and place. For Ngaanyatjarra people, ngurra is life, and life is ngurra. Caring for ngurra, is to care for one’s self, one’s community and one’s culture.

Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands was perhaps the first major exhibition that showcased art, culture, history and contemporary life of the NG Lands. These elements comprise all that is ngurra, and I had the great privilege of working with Ngaanyatjarra people on this exhibition, which shared with audiences the different ways people live on this continent, the ways they conceptualise their homes. As the curator working on this exhibition, I had to ask myself “What does home mean to me?”.

It’s a curious thing, that it took so long for me to truly begin thinking about what “home” really means, beyond the notion of a house, or a distant construct of Country, that I’ve written to, or spoken about in the past. You see, I’ve visited my Country before, both in the midwest and the south-west, but I don’t think I have ever really experienced it in the spiritual or cultural way that Ngaanyatjarra people do. Of course, being on Country feels different to all other places. There’s something calm—a sense ease that comes with being there. But my knowledge of those places is limited, something I hope to remedy in the near future. These are revelations to me in some ways, not ones of sadness, but instead they serve to remind me of everything that has happened historically to make that the case. A curious thing is that the first time I went to the Netherlands, I felt a similar ease, and sense of home, as the feelings I have had on Country, here in Western Australia.

Since the opening of Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands, and all of the work that came before that day on the 12th of October 2017, I’ve been pondering my experiences as a fair-skinned, mixed-race Aboriginal person who has always lived on the traditional Country of other Aboriginal people. I’ve been thinking about my many homes, the relationships, experiences and memories that bind me to certain places, both historically and in the here and now. So before I take you on a journey to the homes of other people, namely Ngaanyatjarra people, it’s important to lay a foundation of my own experiences with the concept of home.

My homes and my life have been across the length of Western Australia: in Perth, Derby, Kununurra, and Bunbury. After my birth in Perth, our family travelled north, first to Derby. My father was following work and family. You see most of his immediate family who were born in Perth had slowly moved away, up the coast. In the early 1980s, everyone lived between Broome and Darwin, including my Yamatji Grandmother who lived in Broome, and my Nyoongar Grandfather who lived in Kununurra. My Opa was born in Soest, near Utrecht in the Netherlands and died just a few years after I was born, and my Nanna, was originally from Falkirk in Scotland. They had left their European homelands, arriving in Fremantle in 1952, and moving to Mount Magnet soon after, where my mother was born.

After our move north, we would visit my Nanna in Perth as much as we could. Her small fibro house in Bentley, a suburb that was home to many migrant families, was our home away from home. She lived there with her companion, my Pop, or Malcolm as my Mum called him. After five or so years in Derby, my parents separated. My mother, brother and I lived a short while in Perth, then after my parents got back together. We moved to Kununurra to spend time with my Grandad, who had been unwell.

In 1990, my Pop Malcolm died, and in 1992 my Scottish Nanna also passed away. We came back to Perth before that, and spent almost 10 weeks with her while she was terminally ill with oesophagal cancer. This was the first time I would watch someone die. My parents decided we needed to get back to school, and just a few days after we set off in the car on the epic drive from Perth to Kununurra, she died, on her 74th birthday. With her passing, my direct connection to our European family and our history was lost. At the age of 10, I didn’t quite understand the impact of this, but recently, on my journey to reconnect with my European family, I’ve been imagining how nice it would have been so sit with her and talk about life in Scotland and Holland, and the same goes for my Opa.

We stayed in Kununurra until just after my Grandad passed away in 1993, and then in 1994 we moved to Bunbury, as my parents had bought a parcel of land there, and were after a fresh start. Instead of building, my parents bought a house, but we didn’t stay there long as a family. My parents had an incredibly difficult relationship, but that’s not a story for here. They separated, for the final time. We sold the house and a year later my mother was diagnosed with lung cancer. After major surgery, and extensive rounds of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, she had a period of remission. Soon after she was diagnosed with secondary cancer in the brain, which was surgically removed. More chemotherapy resulted in another period of remission and I remember some happy moments for our family. Her first grandson Isaiah was born, and she was able to be a part of his life for a short while. Soon after, Mum was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. I was in my first year of university, and within six months, my mum, Elinor Iseger died, just months before my 18th birthday. Since 2002, I have lived in Perth, which is now home.But when people ask me where I am from, I always say Kununurra, this was the place I came into my own, and the place that embraces me when I return. It’s where my grandfather is buried.

My ancestral homes are spread across the world, from Scotland, the Netherlands to nearby places here in Western Australia. Although my connections to these places are distant, they remain central to my understanding of myself. But to say I possess a belonging to any of them, beyond the belonging I have built, is a stretch. And so, this is why my sense of home has always been fractured, and the loss of connection to my various homes early in life, through death, or relocation, has always made it difficult for me to locate my home, the place where I belong. It is no surprise that working on an exhibition all about home presented its own set of personal challenges.

One of those challenges was to try and reconcile the great loss that my family have experienced. We have lost language, ceremony and comprehensive knowledge of Country. So to reconcile this in a way that informed me, rather than simply upset me or angered me, was difficult. I’ve always struggled with the traumas of loss of language and tradition in my work with galleries and museums. Being surrounded by culture, working with communities who have a strong sense of self, who speak language and who practice traditions passed down over thousands of years, is a great privilege. But can also open wounds, and form new ones. I think this was one of the reasons I recently decided to leave large cultural organisations.

It’s hard to put these things aside, but over the past few years, I’ve focused on what I can do here and now. My story and my politics are of course important, but to be more useful to the communities I work with, whose cultures, lives and creative works have fallen under my custodianship as a curator, I’ve tried to focus on the politics and stories of the communities who welcome me into their lives—for without that understanding, how can I share their stories and their realities with honesty, accuracy and respect.

Spending time in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands (NG Lands) was central to understanding what home meant for people, and in introducing myself to their unique worldview. I had the unique opportunity to spend 18 months of my life between the NG Lands, Adelaide and Perth, developing Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands. Prior to undertaking this role, I was aware of art from the NG Lands and the Western Desert region. I was aware of the tjanpi (weaving/woven form), punu (carving/ carved form) and painting being made in these remote communities, but I hadn’t really understood the innovation of Ngaanyatjarra people, and their insatiable desire to reform, reinvent and rearticulate their traditions. It was this innovation that I found so compelling throughout my time working on the project. Beyond those traditions of tjanpi, punu and painting, which define Western Desert art history, are a new generation of makers and storytellers who are recrafting their cultural expression, just as their parents and grandparents have done so in the past. This is a generation of Ngaanyatjarra artists who are connected to the world in new ways, in the age of the internet and in times where communities are becoming more connected to each other through mobile telephone networks.

Through the act of innovating, rethinking how to share a story, or how to share an identity, this younger group of artists is not only finding new modalities to communicate through, but also are opening up Ngaanyatjarra art to new audiences, audiences who find film, photography, sculpture, animation and installation far more accessible than paintings of tjukurrpa, of epic journeys of creation ancestors. For these artists, it’s worth noting, that with every choice they make to work in new ways, there’s always a requirement for negotiation within their communities. Doing things differently, or introducing new ways to share culture must be handled sensitively and done so within the framework of existing culture and custom.

Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands, as an exhibition, united many separate projects into a collective story. Each project had its own unique context in how it spoke of ngurra. The projects that would feed into the exhibition were diverse, as is life in the Lands. In Warakurna, bush trips were being organised for young people. In Patjarr, community was returning home, talking about getting their ngurra back and painting their tjukurrpa. In Papulankutja, groups of ladies were visiting old wiltjas (shelters) and building new ones, while one artist, Pamela Hogan, was creating captivating sculptures made of soap. In Tjukurla, the community was getting ready to set out on journey to take on young man back to their cultural homeland.

One Ngaanyatjarra and Pintupi family decided that their story in the exhibition would be a film of their journey to their cultural homeland of Kurlkurta, a place of great cultural importance to people across the NG Lands and central Australia. On this trip, a young man named Winston Green, would make his first trip home.

Patrick Green, Winston’s elder brother, had been to Kurlkurta a number of times, as he has spent many years living in NG Lands, and also in Kiwirrkurra, to the north of his home community Tjukurla. Winston however, set off on a different path in life. He moved to Perth to study anthropology with hopes to work with Ngaanyatjarra people in developing new opportunities that support people living on ngurra. Winston had heard of Kurlkurta throughout his entire life and had created an image in his mind, constructed from the memories and experiences of his family and community. Having never visited, he had always felt like a piece of the puzzle was missing, and as Winston says, towards the end of the film “being able to go there, and put an image to these stories that I’ve been told, I can definitely go home feeling spiritually and emotionally stronger”. So, in the peak of the summer heat, in November of 2016, a caravan of troopies, full of Winston’s family including his grandfather Simon Butler, the custodian of Kurlkurta, made their way home.

Although I wasn’t on this journey, from what I have been told, and from the video I have seen, this was not a casual drive down a desert highway It was an epic journey involving two full days of driving each way, climbing towering tali (sand dunes), stopping to locate tracks that sat dormant and unused, to change tyres and to refill jerry cans of water at bore holes put in place by renowned artist Anatjari Tjakamarra, Winston and Patricks’ biological grandfather. This was Tjakamarra’s home too, and without his efforts in establishing the bores that both guide the way home to Kurlkurta, and provide water along the way, the trip home would be far more difficult. Along the way, near one of those bores sits a water tank which was airdropped by the army, after people travelling home to Kurlkurta almost died. This water tank delineates the border of Kurlkurta, and the gateway to the site. It is also at this point where all cameras and video cameras were switched off.

Ngurra ngaakuturna marlaku pitjala pukurlarrirra yulapayi.

I come back to this place and I feel so happy it makes me cry.

Faith Butler, 2016

Kurlkurta is a name and a place of great power. It is so important and sacred to yarnangu, that filming and photography at the actual site are strictly forbidden. In the film that emerged from this important journey, Simon Butler, Anatjari’s brother, explains this to the audience and in his message are reminders about the role of the custodians of this Country, the seriousness of keeping both people and places safe and healthy, and the absolute respect that sites like Kurlkurta demand of those people who belong to them. Although the film doesn’t show the actual site of Kurlkurta, it follows Winston’s story, on his journey from Perth, to area of Kurlkurta. It is his voice that narrates most of the film, from weeks before, till just moments after his experience of returning home. One day it will be his role, along with his brother Patrick, to keep Kurlkurta safe for future generations, and the tjukurrpa of this site alive within hearts and minds.

This incredibly personal journey was then shared with strangers, watching on from an exhibition space in Adelaide. I hope that those watching were prompted to think about whose land they are standing on, and everything held within the landscape of this country. In my role as curator, I felt honoured and incredibly grateful to Winston for sharing his story, and also to his family who entrusted it with me, to care for while working on the exhibition.

For Winston’s brother Patrick, it was important to take his brother back to Kurlkurta, and to do so with their grandfather, Anatjari’s brother, Simon Butler. Winston and Patrick have spent much of their life together and have lived together in Alice Springs, Bachelor, East Timor and attended school together in Darwin. Their lives have always been highly connected.

What came of this trip for Patrick was the opportunity to learn more of the stories of this site, to add layers to his understandings of how Kurlkurta lives within him. After returning to Tjukurla from Kurlkurta, Patrick embarked on a new creative journey which took him to Victoria to work with Blueprint Sculpture Foundry on a major sculptural project, using his skills as a welder and boilermaker. While in Victoria, Patrick visited collections that held the works of his grandmother, Katjarra Butler and also the works of his grandfather, Anatjari Tjakamarra, who as I mentioned earlier, during his lifetime left his mark on the path to Kurlkurta in the form of important wells.

- Patrick Green, Wanampi, 2017, recycled and repurposed steel, courtesy of Tjarlirli Art and the South Australian Museum., photo: Brad Griffin

- Tjanpi Desert Weavers in collaboration with Warakurna Artists (Dallas Smythe, Loretta Carroll, Bridget Jackson, Delilah Shepherd, Erica Shorty, Trudy Holland, Dorcas Bennett, Nancy Jackson, Dianne Golding, Selena Shepherd, Noreen Smythe, Katherine Shepherd, Polly Jackson, Judith Chambers, Roshanna Williamson, Eunice Porter, Winifred Reid and Lucy Nelson) Pitja nyawa kulila (Early days family), 2016, tjanpi (wild harvested grasses), raffia and acrylic yarns, wire, courtesy of Tjanpi Desert Weavers, Warakurna Artists, Araluen Art Centre, and the South Australian Museum, photo: Brad Griffin Dallas Smythe, Ngurra: My Grandfather’s Home, 2017, carved, painted and burnt plywood Ara Irititja Wiltja, 2017, carved and burnt, plywood, courtesy of Maruku Arts and the South Australian Museum.

- Pamela Hogan, Lives and works Papulankutja, Western Australia Left to right, top to bottom Teapot, 2017, carved soap, harvested organic materials, found materials Soap Cassette (three), 2017, carved soap, harvested organic materials, found materials Found objects from Papulankutja community, 2017, carved soap, harvested organic materials, found materials Toyota Badge, 2017 carved soap, harvested organic materials, found materials Mobile phone, USBs, lighters and USB cord ends, 2017, carved soap, harvested organic materials, found materials Wirra, 2017, carved soap Courtesy of Papulankutja Artists and the South Australian Museum, photo: Brad Griffin

- Lydia Young, Untitled, 2017 (2), giclée digital print on pape. lives and works in Tjukurla, Western Australia, courtesy of Tjarlirli Art Nyungawarra Ward Tracey Yates, Early Days Toyota, 2017, tjanpi (harvested wild grasses), synthetic fibre, aluminium cans and found objects, courtesy of Tjanpi Desert Weavers and the South Australian Museum, photo: Brad Griffin

Patrick’s return to Kurlkurta with his family, the stories that were shared along the way, and throughout his lifetime, along with re-engaging with the cultural maps of his country painted by his grandparents, resulted in the creation of two incredibly powerful sculptures. His sculpture Wanampi (2017) depicts a serpent of immense importance for Ngaanyatjarra and Pintupi people, the wanampi. Wanampi are incredibly large water serpents and protect waterholes and important sites. Their association and proximity to water holes speaks to the importance of water in desert life. They are the custodians from the tjukurrpa, and their stories speak to the creation of this place we now call Australia.

The wanampi has an ancient belonging to this land and many people know of this serpent as the Rainbow Serpent, a western name that speaks to the wanampi taking the form of a rainbow, again attesting to its binding relationship to water. In the South West, where I am now, the Nyoongar word for the great creator snake, and custodian of water sources is the Wagyl, who rose from a site near Kings Park and created the Derbarl Yerrigan (Swan River) and the Djarlgarro Beelier (Canning River). In the Ngaanyatjarra Lands, Pitjantjatjara Lands and Yankunytjatjara Lands, one of the names for the great creator snake from the tjukurrpa is Wanampi.

Patrick’s large and heavy steel sculpture embodies the importance of wanampi to desert people, and the reverence yarnangu hold for wanampi. The physical weight of the object seems fitting given the cultural weight of the serpent. Although it is only a metre in height, it seems to stand taller, as if guarding its place. It stands like a snake, ready to defend itself and asserting its power to you. Its body seems endless, possessing no apparent beginning or ending, an expansive creature that lives across space and time. Although not encouraged within a museum environment, the bronze snake also possessed the capacity to move. When downward pressure is placed on any component of the sculpture, the snake slithers in its place, expressing the physical life of the wanampi. Within the design of the exhibition, this commanding work was the very last thing a visitor encountered. The wanampi proudly stood watch over ngurra, over the story of Ngaanyatjarra people, and their contemporary expressions of home.

Patrick Green at the National Gallery of Victoria with paintings by his grandmother Katjarra Butler, photo Nyssa Miller.

Patrick took his brother Winston to see his home, Kurlkurta, for the first time. For their grandfather Simon, it signals the beginnings of a new generation of custodians for Kurlkurta, passionate young men who will one day take their own families to this special place, and in doing so reaffirm their fundamental belonging to Kurlkurta, to their ngurra.

The journey to Kurlkurta was a lengthy one, requiring months of preparation, both logistically and culturally. Not all journeys in the NG Lands are of this scale, and people can and do return to places of great significance at the drop of a hat. Sometimes people head off down the road to a place that’s rich in maku (witchetty grubs), or to go swimming at waterholes like Pangurrpirri, a rockhole not far from the Tjukurla turnoff which I visited a number of times. People swim at Pangurrpirri, cook up roo tales, and generally relax at this site, yet it too is home to a wanampi, in the top of the two large rockholes. People are mindful of their behaviour and are respectful of this place. It’s a place to teach tjitji (children) about that wanampi as much as it is an important site of tjukurrpa, and historically it was an essential water source for people moving through the lands.

Places like Pangurrpirri are used by Ngaanyatjarra people socially, practically and culturally. Ngurra is layered in both its use and its meaning. This complex layering of ngurra is like an ever-growing fascia of tjukurrpa, memory, experience. This fascia connects everything to everything else. With each generation, new layers are added to these places, new interpretations, new stories that will be shared into the future. Kristabell Porter, a young woman from Warakurna is actively considering this layering in her photographic practice. Her works speak to the past, capture the present and leap forward into the future. I first met Kristabell in 2015 when she was in Perth for the Revealed Emerging Aboriginal Art Showcase. Since then we have become friends, and I have worked with her on a number of projects.

Kristabell works at Warakurna Art Centre as an arts worker, supporting artists to make work, but recently has become something of a mentor for other young people in the NG Lands, particularly in Warakurna. While working together on Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands, Kristabell was central as an artist, as a facilitator, and as an interpreter. Most importantly she encouraged other Ngaanyatjarra people to come along on the journey. We organised a bush trip, an overnight stay only 20 minutes’ drive from Warakurna. This was a trip focused on young people. As with most things in the Lands, you’re never quite sure what the outcome will be. As we drove off out of town in two 4WDs, Kristabell driving one, and me driving the other, I heard the sounds of the Creekside Reggae Band, a local music group from Warakurna, blaring from the speakers of the car she was driving. We got halfway down the road, and Kristabell turns the car around, signals for me to stop and says “We’re going back that way for yurrunpa”, a tree that at a certain time of year produces an amazing bush honey. After we’d all had our fill of yurrunpa, which involved sucking the honey directly off the tree, or breaking off parts of a branch, we got back on the road. After another ten minutes’ drive, we arrived at Kurrkaparra, her tjamu’s (grandfather) ngurra.

Kristabell Porter and Casey Ayres, Self portrait, 2017, giclée digital print on paper Kristabell Porter: lead artist, Casey Ayres: collaborating photographer, image courtesy Kristabell Porter, Casey Ayres and Warakurna Artists

When we arrived at Kurrkaparra, this time pulling up to a soundtrack of American hip-hop, the young women jumped out, grabbed some crowbars and a couple of shovels and headed towards a group of trees. Kristabell turned to me told me that’s where we’d find ngari or honey ants. Before I knew it, the young women had started digging at two sites within a few metres of each other. They kept digging and digging for around two hours, occasionally finding a honey ant, hoping to find more. It wasn’t a hugely successful day of digging for ngari, but it offered a great insight into the ways young Ngaanyatjarra people bridge and operate in many worlds simultaneously. They are heavily influenced by their own culture and tradition, but equally they draw from and relate to global cultures, listening to music from the other side of the globe while reading the landscape looking for bush honey. Dressed in streetwear, they sat on the ground digging for honey ants. They occasionally get up to see if they can get a signal on their smartphones, to make a call or check Instagram or Diva Chat, a popular social-media platform across central Australia. Kristabell’s knowledge of ngurra, passed to her through her family, her community and a life on the Lands informs everything she does, yet at the same time, she sees herself in a global framework and in many ways, her life mirrors the lives of other young people across the country and across the world.

As an artist Kristabell brings this positioning into her practice, choosing photography as her primary medium, although she is also a painter. Her photography shares stories of her family, of ngurra and of tradition, yet does so through a new lens. Her works document Country, places of cultural importance but also share her own experiences of life. One of the photographs included in the exhibition was taken at the Circus Waters rockhole, an hours’ drive from Warakurna. Circus Waters, like Pangurrpirri is a place of layered meaning. It holds an important ngirntaka tjukurrpa (perente lizard Dreaming). It is the birthplace of living artists who paint at Warakurna and it is also the site of a massacre which took place in the early twentieth century. This massacre came about after some Ngaanyatjarra men stole a camel from some white men, to feed their families. In the events that followed Ngaanyatjarra men and white men lost their lives. So, although this is a place of sadness, people come back, they visit the rockhole, they return to the massacre site and they retell stories of the ngirntaka tjukurrpa and of their families’ experiences of Circus Water.

Kristabell Porter, Circus Waters, 2017, giclée digital print on paper, image courtesy Kristabell Porter and Warakurna Artists

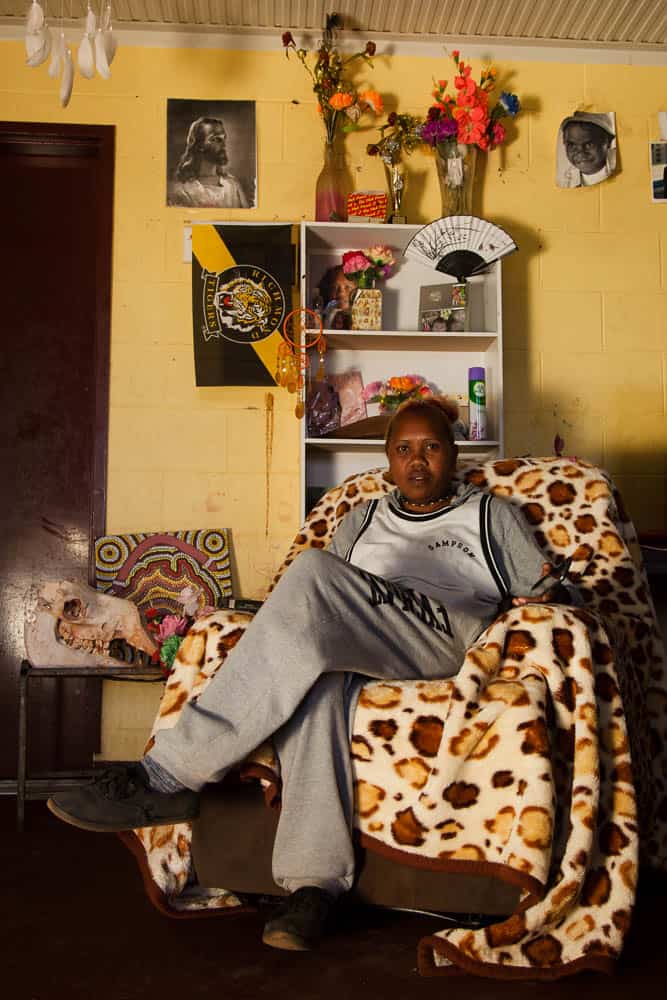

Kristabell’s photograph, Circus Waters, 2017, depicts the rockhole in the background. In the foreground, upon some rocks, sits a camel’s skull adorned in plastic roses, with an empty bottle of Jack Daniel’s sat below. In constructing this image, and curating the objects that sit within it, Kristabell shares a narrative of life in the lands and the legacy of her elders. The camel skull is a regular motif within her work. It symbolises her tjamu, who walked across the NG Lands, relying on his knowledge of ngurra to survive. She recall’s driving and seeing camels that had perished in harsh conditions of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands and this reminds her of her tjamu, and the incredible knowledge that he held and that he passed on to her. The plastic roses, known as desert roses, which are seen on graves across central Australia speak to loss and grief, to remembering those old people and their legacy. The empty bottle of Jack Daniels sat on the ground speaks to the events that happened after the Circus Waters massacre, when all of the white men got drunk after the massacre, after a day of bloodshed and loss. Like many examples of Ngaanyatjarra art, what is held within this single photograph spans many lifetimes, it is a contemporary map of sorts, and in years to come to will hold its place in Ngaanyatjarra art history.

Visiting these places with Ngaanyatjarra people, being a part of the continued animation of these complex places, hearing stories of them being shared as if talking about a family member, or a close friend, filled me with so much gratitude and taught me more than I ever anticipated I would learn about ngurra. Sometime though, I was left feeling heavy, often on the way home. On a particular flight home back to Perth, via Yulara and Sydney, a 17-hour door to door journey, I remember feeling sombre on realising that there are so many families like mine across this vast land who don’t know the stories of their Country, who don’t get to visit those special places. Thinking about this conjured a sadness not just for people, but also for Country. Those special places must be so lonely without their family visiting them, without hearing their voices and knowing their names. That Country must be so worried for them, worried for us.

There were other moments on my journey which reminded me that our stories are sometimes kept safe with others. After completing an interview with Maimie Butler in Papulankutja, we walked outside of the art centre, and she asked me, “Where’s your Country?” I told her about both my Yamatji family and Nyoongar family, and she interjected “Tell me, where were you born?”, and I said, “in Subiaco, not far from King’s Park in Perth, you know that place?”. Maime asked, “That’s where that big snake is hey?” I replied, “That’s the one.” She pointed to the rocky hills in the distance, and said, “See those two lizards over there, those rocks, you can see the black one, and the other one, that’s wati kutjarra (two men).” I looked and easily saw the forms in the landscape. Maimie continued on, “That’s that big snake right there. When he travelled this way, he turned into those two men, wati kutjarra, and we know that whole story, from when he travelled from the south, to where he finally ended up.” Maimie had, in that single moment placed me within her landscape, within her ngurra, by locating something connected to me ancestrally and culturally. It wasn’t so much a repatriation of story, but more an acknowledgement of our connection to each other. This was a gift that I couldn’t have ever dreamed of nor asked for.

- Bush camp at Kurrkaparra, the ngurra of Kristabell Porter’s tjamu (grandfather), photo: Glenn Iseger-Pilkington

- Country near Warakurna. photo: Glenn Iseger-Pilkington

The lives of Ngaanyatjarra people remain heavily influenced by pre-contact traditions and enduring knowledge. This knowledge of country, and the memory and history embedded within ngurra is kept alive through sharing stories particular to place. A rock, a tree, a waterhole; each is full with story and history. Many of these narratives are full of celebration, humour and resilience, but equally many are of sadness and grief, and some are places of violent encounters that came through contact with Europeans. As Aboriginal people, our inheritance comes in the form of our cultures, the memories of our ancestors and our ties to places, people and the natural world. For many people including myself, these inheritances also come in the form of trauma, loss and displacement.

What was most profound for me was witnessing the way that Ngaanyatjarra people look to the past. They do so in a way that places great importance on the coexistence of history, emotion, and memory, inherently aware that this is central to their selfhood. All stories, from the joyous to the sorrowful have a belonging, they are a part of who we are.

For a long time, I’ve cultivated ways to avoid sharing my own story, after years of having that story define me. After my experiences working with Ngaanyatjarra people, I’ve come to understand the narrative of my own life in a different way. In my adult life, I’ve focused very much on the present, and the future, with a propensity to sometimes live too much in that future-space. I’ve tried not to look back, for fear that the past will again define me. Working with Ngaanyatjarra people had me challenging these behaviours. I have found myself turning back, looking to the past, encountering those difficult times, traumas and loses with a new focus, as if meeting them again for the first time. In this act of revisiting my past there is a rebuilding of my history, a repair which at any other point of my life was seemingly impossible.

This revisiting has not been an easy task. At times it’s been quite painful. But it is one that has provided me with more self-awareness and a great understanding of myself. We cannot run from or ignore the past if we want to move forward, but instead we must find ways to talk about it, to pay homage to it, to keep the memories, good and bad, alive in our minds. Just like the Ngaanyatjarra Lands, this entire continent has an Aboriginal history – it is Aboriginal Land. It also has a more recent history, a painful history for this continent’s First People, which has left scars on our entire community.

Looking back on what our ancestors have or haven’t done, doesn’t make us culpable. It simply informs us and can foster new understandings of, and greater compassion for each other. Our connections and deep attachments to our homes are personal and intimate, whether they are houses lining the streets of Fremantle, towns in the Wheatbelt or vast physical and cultural spaces of the Western Desert. What we must endeavour to keep in our collective consciousness as a nation, is that these lands have been peoples’ homes, peoples’ ngurra, for tens of thousands of years. Prior to the invasions that initially took place on the coastal fringes of this continent and its islands, these places were known intimately, they were cared for as if extensions of the self, they possessed names, songs and ceremony, and at no point, were the offered up for the taking.

Author

Glenn Iseger-Pilkington is a Wadjarri, Nhanda and Nyoongar man and a member of a Dutch and Scottish migrant family. He spent the first half of his life living in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and has since 1994 lived on Nyoongar Country in the South West corner of Western Australia and currently resides in Perth. Glenn undertook his formal art training at the School of Contemporary Art, Edith Cowan University, majoring in Printmaking. After more than ten years working in major public institutions, he now runs GEE CONSULTANCY, a small creative consultancy which works closely with artists and art centres. Prior to this Glenn held the position of William and Margaret Geary Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art and Material Culture, South Australian Museum, where he curated ‘Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands’. From 2014 to 2016, Glenn was the Curator Content Development, New Museum Project at the Western Australian Museum and from 2007 until 2014 he held the position of Associate Curator of Indigenous Objects and Photography at the Art Gallery of Western

Glenn Iseger-Pilkington is a Wadjarri, Nhanda and Nyoongar man and a member of a Dutch and Scottish migrant family. He spent the first half of his life living in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and has since 1994 lived on Nyoongar Country in the South West corner of Western Australia and currently resides in Perth. Glenn undertook his formal art training at the School of Contemporary Art, Edith Cowan University, majoring in Printmaking. After more than ten years working in major public institutions, he now runs GEE CONSULTANCY, a small creative consultancy which works closely with artists and art centres. Prior to this Glenn held the position of William and Margaret Geary Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art and Material Culture, South Australian Museum, where he curated ‘Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands’. From 2014 to 2016, Glenn was the Curator Content Development, New Museum Project at the Western Australian Museum and from 2007 until 2014 he held the position of Associate Curator of Indigenous Objects and Photography at the Art Gallery of Western

NGURRA: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands was exhibited at the South Australian Museum from October 12, 2017 until January 28, 2018. The exhibition was made possible through the hard work, determination and generosity of Ngaanyatjarra artists and communities with support from Kayili Artists, Papulankutja Artists, Warakurna Artists and Tjarlirli Art. The project was supported by the South Australian Museum and TARNANTHI: Festival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art.