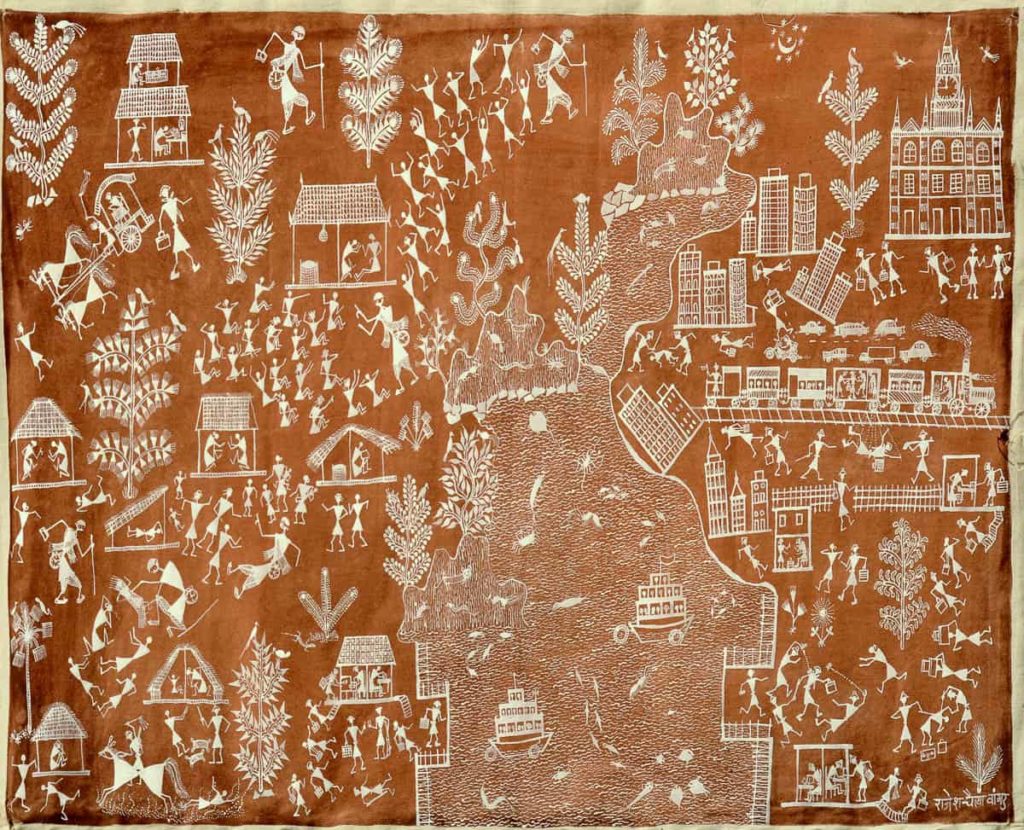

- Rajesh Chaitya Vangad Maharashtra, Gandhi Katha 1 Warli Painting, 31x54cm

- Mata ne pachedi

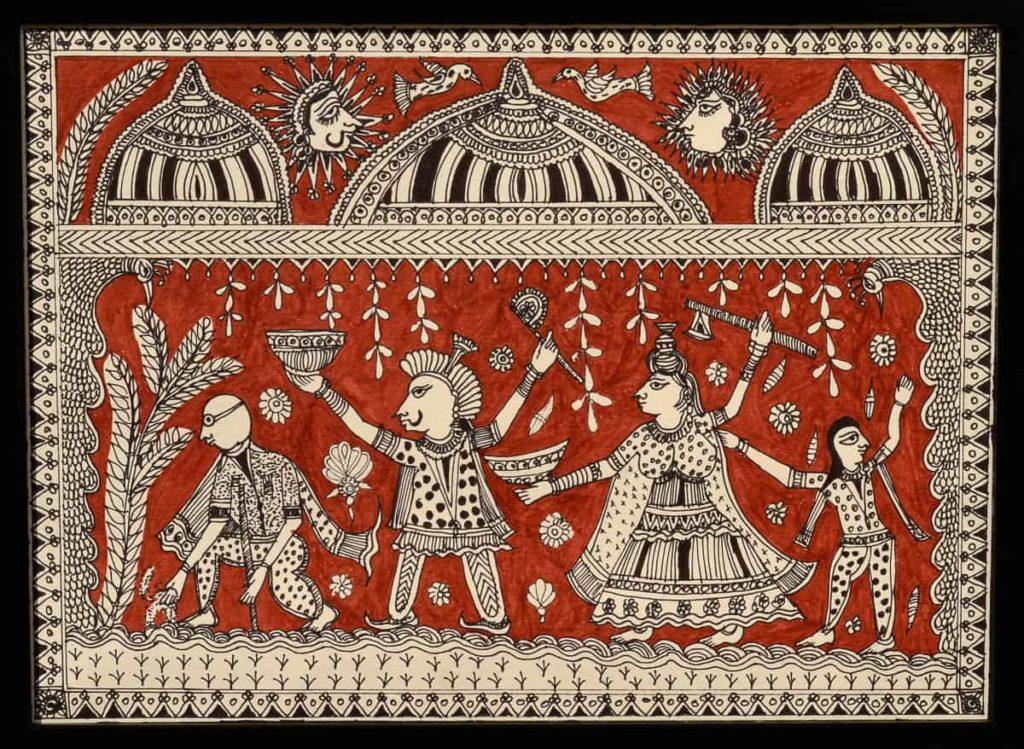

- Orissa patachitra, paper

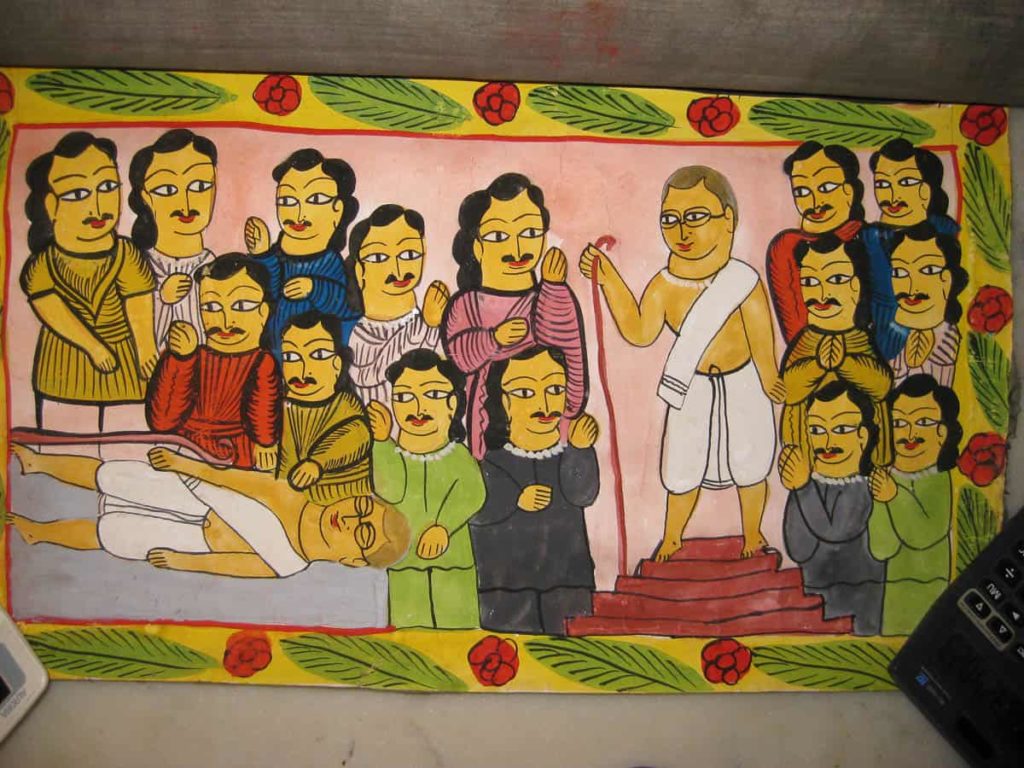

- Patachitra Bengal, Bapu, 2012

- Bapu with the Tricolor Madhubani Painting Bihar, 16x8cm

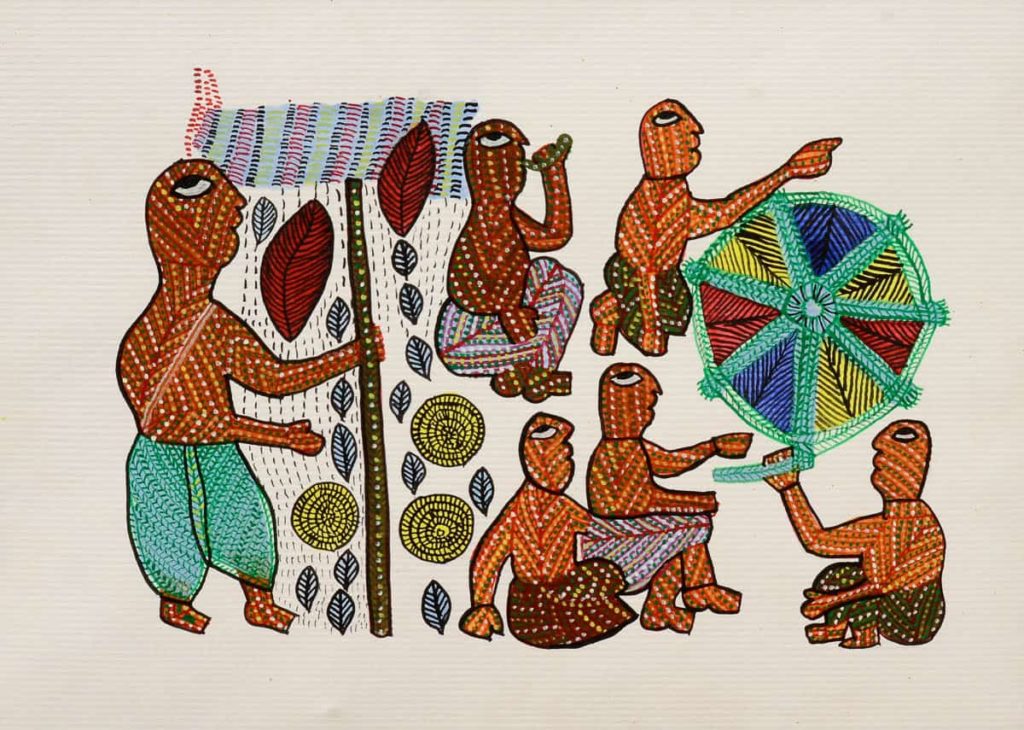

- Jharkand applique with charkha

- Punjab phulkari

- Patachitra Bengal, Bapu, 2012

- Patachitra Bengal, Bapu, 2012

- Rani and Probir, Bapu, 2012

- Mohan Singh, Bapu with Villagers Gond Painting, Madhya Pradesh

Sunaina Suneja curated Bapu: The Craftperson’s Vision for the Confluence festival of Indian culture in Australia. She reflects on the way works such as the patua tell the story of Gandhi today.

I have been working with our craftspersons, both textile and objects, for over 25 years, so I knew some of them, but I naturally went out of my way to discover new ones to ensure the exhibition would be as all-encompassing as possible. So it grew organically and I continue to add new works. For example, I will be bringing to Brisbane a just finished work of Mahatma Gandhi in chikan embroidery Chikan embroidery has not featured earlier in this exhibition, and I am delighted, because I consider it to be the first textile craft I worked with personally, as a young college-going student in the 70s!

Mahatma Gandhi believed the charkha (the spinning wheel) would transform the lives of the poorest of the poor and that was his focal point. The charkha’s final product, khadi, handspun and handwoven, then took political centre stage during India’s freedom struggle. The British resorted to banning its wearing, including the small hat commonly known today as the “Gandhi topi”, as it had become a powerful visual symbol communicating solidarity with the movement.

And he was zealous in expecting everyone to spin, men and women both. Spinning was traditionally considered to be a woman’s inner courtyard activity and thus Mahatma Gandhi also succeeded in “neutralizing” the gender bias inherent to it, at least in his time.

So keeping history in mind, yes, khadi’s meaning has changed, but we gained Independence 70 years ago and most things evolve with time. However, it continues to be linked to the country’s history and to Mahatma Gandhi, even in the minds of younger generations.

We know Mahatma Gandhi to have been a visionary way ahead of his times, a man of many parts. His personal requirements were described as frugal, but in fact he was environment-friendly, sensitive to the limitations of natural resources. As he put it succinctly, “There is enough for our need, but not for our greed”.

Similarly, in advocating the use of khadi, Mahatma Gandhi was also promoting self-sufficiency in villages and the consumption of locally produced goods. Again he was thinking ahead, to sustainable patterns of living which we value so greatly today. He has left us the wisdom of his words: “Let’s be the change we want to see in the world”. Most importantly, khadi continues to be an important income-generation activity for all those who are involved in the various stages of its production.

One of the artists who tells the story of Gandhi in this exhibition is Rani. I was introduced to her soon after I started working on my exhibition, Bapu: The Craftperson’s Vision. She spoke but a few words of Hindi and my Bengali is more sparse, so we communicated through her nephew who travelled with her to participate in this exhibition.

Both come from a family of patuas, itinerant storytellers of West Bengal, who travel through villages, carrying a few hand-painted scrolls which they unroll as they sing its story. These scrolls are called patachitras, literally paintings on cloth or even leaves.

The scroll recounts the legends of two of India’s ancient epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. These same stories continue to be retold even today in villages along with newer ones, including 9/11 and the tsunami which hit coastal India in 2004.

In the past, women rarely painted the scrolls, nor did they travel with the menfolk. Today they not only paint, they also travel to government-sponsored events organized within India and internationally as do the men.

It was very different in the past as a group of three to five men would travel from village to village with their patachitras, unrolling them as they sang without any accompanying instruments, providing entertainment to an audience of villagers. They would receive gifts of a few kilos of rice, for example, but little money in those days, and return home in a few weeks.

From a core group of four to five families of patuas, the numbers have now grown to 300 artists in their particular village and Rani’s own extended family consists of at least 20 artists.

The reverse side of these long scrolls are gummed with old muslin saris to make the canvas stronger. A particular herb is used alongside the gum which acts as a repellent to bugs. As paper was in short supply in times past, villagers would gather together any pamphlets announcing programs or even doctors’ visits, the precious paper carefully gummed together, long enough to paint a scroll. One member of the family would compose a song to accompany the narrative of a scroll and the others would learn it.

During the colonial era in India, patuas also took on the task of propagating the anti-British line through the villages. Rani’s nephew has heard the story of his own paternal grandfather having been imprisoned for a scroll which depicted one such narrative.

Today the patuas are happy to incorporate fresh storylines into their patachitras, to attract new audiences. For Bapu: The Craftsperson’s Vision, Rani made a four metre long scroll, which illustrates the life of Mahatma Gandhi. In her sweet melodious voice, she sang of the Gandhi Katha (story), from his birth to his assassination. Vignettes of his family, his travels across the seas, khadi and the charkha (spinning wheel) and the making of his destiny are chronicled in this scroll.

Previously, patachitras were not sold as individual items. But for the past 25-30 years, smaller format individual paintings have been now available for sale.

During the recent exhibition at QUT (Kelvin Grove Campus), Brisbane, I walked visitors in groups or individuals through the exhibition, recounting stories from Mahatma Gandhi’s life, his emphasis on charkha-spinning and khadi, and of course, the different crafts included and the craftspersons who made the individual works. I shared the affectionate accounts of their depictions of Bapu, when they chose to show him in their midst, in their villages and a part of their lives.

The response to the exhibition and the crafts of India was very warm and I have returned home with warm memories.

Author

Sunaina Suneja lives and works in Delhi, out of her boutique in Hauz Khas Village. She calls herself a “Khadian”, given her long years of work and commitment to Khadi. All the work she has done with the other textile crafts of India has stemmed from that one singular passion. Indigo dye is a particular passion and she has dedicated exhibitions to it since 1997. She has also revived the traditional style of Punjab’s phulkari embroidery. Now she would like to renew her bond with Kota Doria, Rajasthan’s finest weave. See website www.sunainasuneja.in.

Sunaina Suneja lives and works in Delhi, out of her boutique in Hauz Khas Village. She calls herself a “Khadian”, given her long years of work and commitment to Khadi. All the work she has done with the other textile crafts of India has stemmed from that one singular passion. Indigo dye is a particular passion and she has dedicated exhibitions to it since 1997. She has also revived the traditional style of Punjab’s phulkari embroidery. Now she would like to renew her bond with Kota Doria, Rajasthan’s finest weave. See website www.sunainasuneja.in.

Comments

Fascinating.

Enlightening and entertaining.

Inspiring and moving.

Thanks Sunaina

When are you exhibiting in Delhi?

Hi Sunaina, nice to know about the work you are doing. My best wishes for all the success. Happy Gandhi jayanti. Have a pleasant day.