- Herding the cattle – en route to Hodko

- Shamji’s father removing ticks from a cow’s tail, home-cumwork shop of Vankars

- Uddo Village, Banni – new Bhungas, January 2019

- Meenu sits on her haunches at the edge of a manji, working on a piece commissioned by NGO Kala Rakshak, Bhujodi Village.

- Spinning the freshly carded wool at workshop of Vankar Shamji Vishram

- Vankar Shamji Vishram explaining the subtle nuances of the indigo vats

- Interior and Roof of traditional thatched Bhunga, Uddo Village, Banni, January 2019

The very mention of Kutch evokes images of a romanticised, stark and parched, ochre landscape replete with circular mud bhungas with their conical thatched-roofs, camels, buffaloes and colourfully embellished fabrics. Local legends are many and one cites the Kutch peninsula to be an impermanent landmass arisen from the Arabian Sea like a turtle or Kachua, which will one day re-submerge into those very waters. Frequent droughts—devastating earthquakes and floods onto the Ranns that turn Kutch into an island—are features of the terrain that the people who inhabit the area have devised creative ways to confront the rigour through vibrant textiles, woven, printed and embroidered.

Even so, it has been the home of nomadic pastoral communities for generations. The Banni grasslands that sustained them are becoming sparse and free-grazing is no longer the major resource of fodder for sheep, goat and the highly pedigreed and much sought after cattle bred in this region. Upcoming industries offer jobs to accommodate the changed landscape and its revenue models, but these nomads (who are not really nomads any more, for most are now settled in villages) haven’t taken up the available educational opportunities to take advantage of such employment. Many of the weavers and printers are quite well educated, with some boasting of college degrees, but they’ve made a conscious decision to stay with their time-honoured trades of weaving and printing. However, for those without much formal education and aptitude beyond cattle rearing and breeding, the lucrative, vendible skill of needlework that different communal clusters once did for themselves, has given women their own income stream.

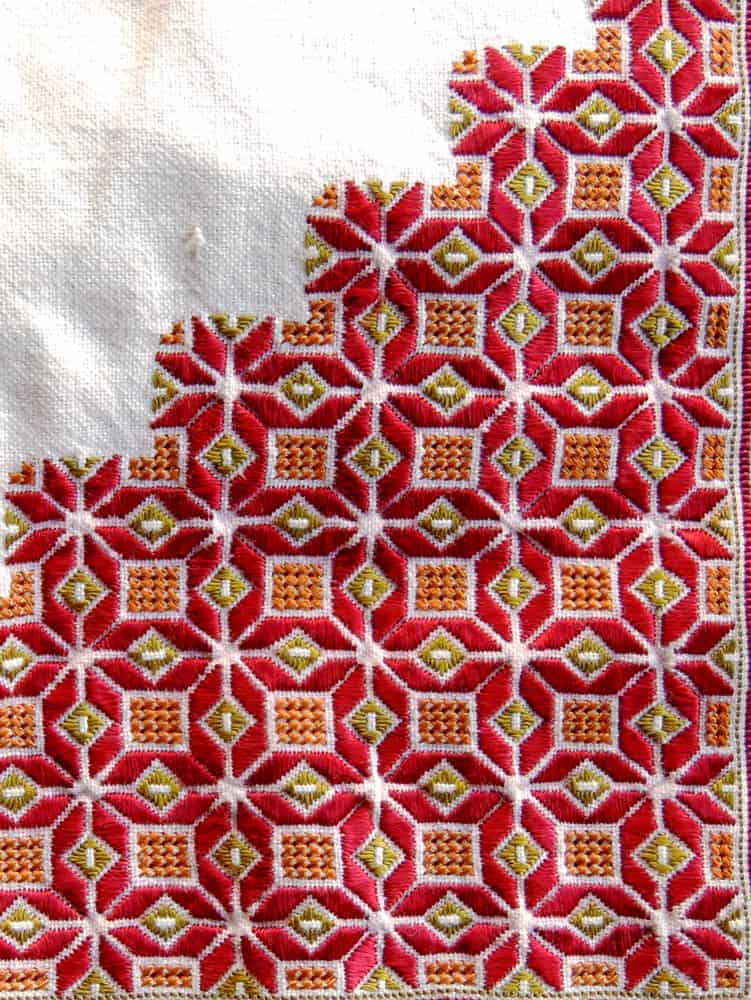

Each collective had definitive stitches and patterns that were passed on from mother to daughter, as much a symbol of personal expression as identity markers for different groups. While still a dynamic living convention, its usage in the contemporary life of the traditional makers is, nonetheless, a diminishing one. Neither women nor men, wear these garments as much; for time and energy is engaged in providing wares for urban markets where their hand-work is in great demand.

While trying to locate the home of a particular craftsperson in the village of Hodko, the driver stopped the car at a hamlet to ask for directions. A woman from the local Mutwa community came running out of her home brandishing vividly decorated kanjaris (backless blouses) thinking that I was there to buy embroideries. In the silence of that endless desert landscape, kicking up a trail of dust as she ran forward, her frenzy, akin to marketing tactics in crowded urban bazaars, was disconcerting even as it was a telling comment on the sign of the times.

In contrast, at an earlier, recent visit to a home in Bhujodi, I had been charmed to see nineteen-year old Meenu, of the Meghwal community who practice Soof stitch, actively involved in personalising handkerchiefs, the ritual betrothal gifts for their fiancés. An older, much married woman, Neela, showed the hankies she had once made, and a young man, proudly took out the kerchief his fiancé had recently sent him. Meenu and Neela are engaged primarily by Kala Raksha or Shrujan and the delicacy in items they custom-made, using the counted-thread method of surface satin stitch or Soof, compared to the commercial pieces they were sewing, was noticeable. It was a reminder of the inevitable difference in the output when something is a labour of love and when it is done only for trade. Times have changed, necessity compels people to adapt to altered circumstances and is as much a testimony to their creative ethos, as dowry and intimate gifts once lovingly fashioned. However, as part of their revival ethos, Shrujan has also contracted exquisite pieces from the Kutchi needlewomen. But, understandably, not all needle endeavour is of the highest standard and not every woman has the same level of expertise.

Shrujan, a not-for-profit organisation empowering craftswomen in Kutch since 1969, has been a key facilitator of sustainable livelihoods, especially for those displaced from Pakistan in the 1971 war. Spearheaded by the vision and wisdom of Chandaben, matriarch of the Shroff family, kits—of cloth pieces with designate skeins and some with outlined patterns—for Ahir, Aari and some Pakko and Mutwa styles, are delivered to their homes. Allowing them to earn without any rupture in domestic routines and responsibilities. This system also honours time-worn edicts upheld by communities such the Sodhas who, even to this day, do not permit their women to leave the threshold of their homes, unchaperoned. After decades of conversations and observations of various cultural idioms and embellished expressiveness, Shrujan expanded its activities to include research and documentation of these diverse community lives and the embroideries imagined and executed by each. This led to the establishment of a museum, The Living and Learning Design Centre (LLDC), at Ajrakhpur, inaugurated in 2016.

- Maggie Baxter, Here and There 2004 – details

- Maggie Baxter, Slippage 2013

- Maggie Baxter looking on as Gangba works, the kitchen behind her

I was excited by the idea of such an institution and of feasting on the rich lore and designs of this region—all under one roof. My first visit to Kutch was in 1989, but I hadn’t been back since. So when the museum opened, I decided it was time to revisit and planned it to coincide with fellow artist and friend Maggie Baxter’s schedule. Intrigued by her long-term involvement with Kutch, I had been keen to observe her create at-site, ever since we met, and it seemed to be the perfect opportunity to do both. What was also enticing was the prospect of studying the documented history and also wandering through the villages seeing the inclusion of disparate disciplines, such as Maggie and other art and design practitioners, within the ambit of established fabric-making and marking techniques of the region.

Maggie too, had made her first foray into Kutch around the same time, thirty years ago. With a background in sculpture and not textiles, she confesses to having had neither “a burning interest in the crafts of the region”, nor had heard of Kutch until a chance meeting in Perth with Kirit Dave, designer and family member of Shrujan. He encouraged her to visit, and she did, alluding to this introduction as the beginning of “a slightly dysfunctional long-term relationship” with the region and its talents.

Kutch, she says, “has an amazing confluence of textile crafts stemming from centuries of migration from what are now Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Middle East, and other parts of India.” Intrigued by the endless possibilities in block printing—”not within the existing traditions of exquisitely accurate registration of patterns, but more in the way of reproducing an abstracted form of drawing: lines and marks floating without symmetry on the fabric”, the Ajrakh technique using natural dyes, iron filings, alum and mordants, as also local ornamentation characters, became a visual marker of this Australian artist-writer-curator’s creative oeuvre.

Ingenuously nurturing an unusual, long-distance artistic practice with Kutchi textile-making as its fulcrum, her linear mark-making tendencies were perfectly synched with impressions created by carved wooden blocks, but it took “longer to decode embroidery” and work out how to connect it. From a journal entry (December 2003), one glimpses a thinking process consciously striving to include the native palette of textures and colour, when she says: “As I was drawing I started to think about using the blocks in simple, but strong graphic black and white, with a large border of brightly coloured embroidery. Maybe this will be left to Rabari women, or maybe I will do the design and get it done with Sodha women in Pakko. This is in keeping with local odhnis [shawls], which have fields of black wool with simple tie-dye and then amazingly rich borders.”

Although it was the museum that was the impetus for this trip, in January 2019 I didn’t get to see inside it until the penultimate day of my stay. Instead, I wandered around with Maggie visiting the printing establishments in Ajrakhpur, and also Gangaba of the Sodha community, in Bhujodi, who was embellishing one of Maggie’s block-printed panels with a variation of “Pakko”. Pakko literally means solid. The outline is done with a square chain-stitch, but the filling is a dense variation of a buttonhole stitch, which lends a raised appearance. Maggie, however didn’t use it quite so, leaving many loose ends, allowing the needlewoman to manoeuvre the tack in a much looser form.

- Detail of Soof embroidery on commercial piece commissioned by Kala Rakshak, Meenu at Bhujodi Village, Kutch

- Vankar Shamji Vishram – new designs

- Detail of Soof embroidery on Neela Sehra’s pillow cover – details of Soof embroidery

- Neela Sehra’s trousseau pillow-cover

- Soof Embroidery motif on a handkerchief, Bhujodi, Kutch 2019 – gifted to Jeetendra by his fiance

I watched as short, stubby fingers, with chipped, dull, bronzed-maroon nail-polish, deftly handled the sui-dhaga. A bespectacled Gangaba, with faint strands of white, shining off her otherwise, glossy black tresses, sat cross-legged on the contemporary tiled floor of her home, on a plastic floor-covering, woven along the lines of the bamboo chattai. She covered her head with the pallav of the mill-printed polyester saree she had worn. It was imprinted with multicoloured polka dots and mock ombre-dyeing. Most unlike the conventional garb of her people that once comprised a ghaghra (gathered, ankle-length skirt) richly embroidered kurti-kanjari (layered blouse) and tie-dye odhani (head and shoulder wrap) that was usually paired with abundant silver and gold jewellery, closely resembling costumes worn in the deserts of Rajasthan.

Extending from the top of her saree-draped left thigh, where she loosely secured it with pressure from her left elbow, a length of off-white cotton, hand-block-printed with iron-black cursive letters, of signatures in the English language, spilled out in front of her, rippling forth—an estuary of cloth that swathed the matting she sat upon. Maggie was seated, on a bed, to her right and Sandhya, a local Jadeja girl employed by LLDC, passed onto Gangaba, instructions in Kutchi which neither Maggie or I speak nor understand.

It was a warmish winter morning. Weak rays of the sun filled the open doorway. There was no distinction between living areas of home and her workspace. As we entered, we had passed a young calf tethered to a tap, under the deep rust of a coloured ceramic sink, sunning itself out on the haphazard, broken-stone floor pattern of the open courtyard. A tall woman, probably a sister-in-law of Gangaba, wearing a bright, ultramarine blue saree was engaged with the laundry. Round metallic tubs of soaked clothes circled the hand-pump, while already washed garments hung from a line above. Carelessly strewn on the balustrade of the staircase leading up to the rooftop of the single-storey home, was a traditional local-wool shawl with its definitive extra weft effect, in hues of beiges and brown with just the hint of more vibrant colours; part of the garb that once defined the Rabari community of Kutch, usually worn by men. It’s casual placement on the steps of a Sodha home, in close proximity to the saree clad woman washing clothes, carried the implication of belonging to her. Making one note how patterns that earlier demarcated gender and communities, now blended into a generic Kutchi dress-code. The room we sat in led into the kitchen area, a semi-open-plan arrangement where glass, stainless steel and plastic utensils lined shelves that had been placed in a large void in the soft-green painted hues of a wall, adjoining the kitchen, behind the bold geometric-patterned, mill-printed sheets covering the manji or bed, that Maggie was seated on.

Head in her hands, bent forward, she watched Gangaba threading her needle, drawing it into and out of the cloth, embellishing designate parts; probably thinking of where next she would like the white yarn in Pakko to be raised from the printed text, or should it be black or red filaments this time. And how much of the loose ends to leave and where. I watched this process and wondered at the dexterity with which necessity brings in unquestioning change and traditions mature. Having collaborated with needlewomen and block printers in Kutch for three decades, Maggie Baxter is as much a part of the growth of the textile practices of the region, as the more conventionally biased embroideries sold in the shop at Shrujan or designer labels/boutiques and chains of stores who have prospered through the material from Kutch. None of these, have much that harks back to the sanctity of stitch, pattern and region they originated from, but each have been adapted to fit the contemporary, globalised mould. There is a twinge in the loss of the past, but heartening in the continuance of traditions of the sewing, of a practice that grounds and centres the maker, even if she is not doing something she can relate to nor understand. The very act of passing twisted fibre through the minuscule eye of a needle and pulling its length in and out of the fabric, in a repetitive mode, no matter how many loose ends are left on the surface, overshadows the open-chain and filler button-hole markings, once a statement on the dress of the Sodha clan. Through the hands of Gangaba and other such women, the thread of continuity is conceded.

With sixteen distinct communities to document, the LLDC museum is an intense space to be visiting. Life-sized mannequins wearing dresses of different groups, video images and large panels of text telling about history, culture, adornment and legends, one is drawn into the magic of the nomads and this fabled land. But, just one visit is far from enough to take it all in, even a lifetime wouldn’t suffice. The Sodhas, which Gangaba hails from, are a Rajput community from Pakistan, apparently the only Hindu Rajputs in the region and their migration to Kutch started in 1971 after the Indo-Pak war. Originating from Thar Parkar in east Sindh (Pakistan) with relatives in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Kutch, they integrated easily and led a contented life in Kutch. There are now thirty-two Sodha villages comprising twenty-five thousand members of which four thousand are artisans. I was more intrigued by the Jats who, like me, do cross-stitch work, but it wasn’t possible to travel across to Sumrasar to see the Jats and even though the museum had extensive material on their creations, watching Gangaba doing Pakko or Neela Sehra and Meenu showing off their Soof skills was, quite naturally, a more memorable impress.

Even though embroidery traditions excite the artist in me because of my own preoccupation with this activity, my love of thread comes from my training and specialization as a weaver. So our next stop to the home and shop of Vankar Shamji Vishram in Bhujodi was a bit like a homecoming, only more special. Though not extensively, I have designed for many weavers and villages in rural India and discontinued because I was uncomfortable with imposing ideas that came from my western education and a sensibility honed through urban markets. Like other designers, I had been hired by government agencies to bring in just these perspectives, but pushing for colours and textures so alien to their hands, created many conflicts and I felt that neither was it an organic process and nor could I play god and promise business overnight. Working with government agencies is fraught with complexities that go beyond the purview of design and eventually even samples didn’t reach destinations they were targeted for. This was probably the shove I needed to evolve my own art practice as an artist-craftsperson, but what I saw in the fabrics created by Shamji was so reassuring, so beautiful and wholesomely devised that I was brought to tears.

I have always held that the great crafting traditions of this country arose not only through enlightened patronage, but also because of the ingenuity and passion of the maker. I have noted again and again that commerce alone, no matter how lucrative and well-paid, doesn’t lend itself to excellence, but personalised involvement of the artisan can create magic such that is unimaginable. And the delicately hued shawls and sarees that Shamji lovingly unfolded, drawing motifs from his forefathers, learning how to dye with natural processes and through interactions with many designers, were the fruits of fostering a unique aesthetic, arising unquestionably from generations of Kutchi weaving. The way in which the patterns and colours integrated, the evolution was evidently personal as much as it was in cloth that had the mark of an authentic hand, the sensibility of a man rooted in his culture, yet willing to embrace change. The passion, the commitment and the dedication to a slow process where smell and taste define the readiness of the indigo vat and other such subtle and delicate nuances integral to dyeing, as also the labour of the loom, which is no less arduous, were all visible in the fragrance of freshly carded wool, sleeping cattle, cow dung, charkha and pit loom that surrounded the home cum atelier of Shamji and his family.

It was as if the concepts of living and learning documented at the museum, spilled out into processes very much a part of everyday existence. In this far corner of the Indian subcontinent, in the relatively unadorned countryside of Kutch, nomads who once envisioned dreams and desires through their lushly embroidered goods to compensate the arid landscape, continue envisioning through the threads that bind them to the land. Drawing from the tradition of a culture that has seen countless changes and also the gist of continuance, such that the Vankar (weaving community) belief that ” a tradition will be lost and a new way of life will evolve” has become a verifiable, living and learned reality of the wanderers now settled in Kutch. A vivid tapestry incorporating the varying wefts and hues of individuals of tribes within its folds and from far off-lands, defining, exploring and re-defining boundaries of culture, expanding the lexicon of cloth.

Author

Gopika Nath is a textile artist and writer preoccupied with the idea of personal histories and how they influence one’s artistic practices and creative expression. Personal histories are not isolated. Infinitely interlaced—culturally, politically, socially, economically and otherwise, they make-up the different templates of an expansive chronicle of human life. In her quest to construct such a “narrative quilt”, she invites artists and writers and anyone else interested in sharing their stories, to contribute to the Personal Threads Project. Some stories, (tagged as “Personal Threads”) have been uploaded on gopikanathstitchjournal.blogspot.com

Gopika Nath is a textile artist and writer preoccupied with the idea of personal histories and how they influence one’s artistic practices and creative expression. Personal histories are not isolated. Infinitely interlaced—culturally, politically, socially, economically and otherwise, they make-up the different templates of an expansive chronicle of human life. In her quest to construct such a “narrative quilt”, she invites artists and writers and anyone else interested in sharing their stories, to contribute to the Personal Threads Project. Some stories, (tagged as “Personal Threads”) have been uploaded on gopikanathstitchjournal.blogspot.com

Comments

I have been to the Living and Learning Design Centre and met both its architect and the curator. I would have to say it is the most astounding museum I have ever visited. When I asked in 2016 if there was a book on the displays the curator informed me that no, they had literally hundreds more textile pieces archived ready for future displays. Anyone I’ve met who has visited has the same view as me, a stunning vision which celebrates the imagination and work of hitherto unsung women celebrating their art. Wonderful.