Tyson Yunkaporta reflects on the fluid connections made by serpent beings between peoples and nature.

A couple of years back, my partner Megan and I started a journey that was patiently facilitated by Garland, yarning with craftspeople and traditional knowledge keepers from around the globe who hold the wisdom of water spirits and great Serpents. In our house, we understand Serpent Law from a Central and North Queensland regional perspective, so we call him Thaypan from our Pama side and Kabul from our Murri side. We also understand the connective songlines of Snake entities that criss-cross our continent from our Indigenous relations and ritual exchanges all over Australia.

However, this Law and Lore is not limited to our shores. Around the world, there are stories of great Serpents running through the living body of the earth as threads binding us all together in a patchwork quilt of bio-cultural diversity. Although none of these entities are verifiably real, we all feel their presence, just as we feel the invisible force of love, and we believe that the stories humans still tell about them contain some useful wisdom that might help us all today.

The Serpent takes many forms in time and space. He may be a male shooting lightning from his scales in a particular site and season, but in another place or different season, the same entity will have eggs. It can be mammalian, with bosoms nourishing the land with milk, or crocodilian at another site, and may even have feathers or a huge, shining penis. It may even be a penis, sung into serpent form to trick the unwary.

Serpent Lore shows us that boundaries are fluid.

Serpent Lore shows us that boundaries are fluid. Borders are relational spaces-in-between that are dependent on context rather than permanent defensive barriers to be surveyed and contested. However, even in Aboriginal Australia, monotheism from the global north has undeniably brought competition, superiority and exclusion to our shores and into the hearts of our People. It has introduced some troubling ideas about the Serpent as an ‘ancient enemy’.

With the historic rise of this strange story around the world, dragons have been slain, snakes crushed beneath heels, and mythical holy warriors have vanquished the pagan beasts, awaiting their death and ascendance so they may join their deity and his prophets to sit in splendid dominion in another world.

Iran

Bahram killing the dragon – Chah-namah. Topkapı Palace collection, Folio 203 Verso. Painted in shiraz 1370. Wikimedia.

We explored this idea further with Nargues Teimoury, an Iranian scholar who told us that Dragons in her tradition are gigantic snake-like creatures with wings, originally the enemies of Tishtrya, the god of rain, who was part of a polytheistic pantheon that existed before Zoroastrianism.

Persian Dragons are not beings of fire, air and water as in other traditions. They are evil beings of dryness who suppress these sacred elements. Nargues said that without the dragon, there can be no enlightenment because if there is no beast, there can be no struggle within to conquer the evil of one’s own heart and become a hero. How can you be a hero if there is nothing to slay?

But in every culture, whether the great Snake entities are good or evil, they all guide us through times of change and upheaval in our struggle to maintain balance between creation and destruction, society and nature.

Mexico

Depiction of the two forms of the god Quetzalcoatl on folio 19 of Codex Laud, a pre-Hispanic Mexican manuscript possibly made in the 15th century. His form as the feathered serpent, celestial deity, is depicted at the left, and his form as the god of the wind Ehecatl is seen at the right, with his characteristic completely black skin, beard and red mask. Wikimedia

Next, we spoke to Eduardo Aguilar Zarandona, a Meso-American thinker and scholar from a family who keeps the old Serpent Law of Quetzalcoatl. This entity belongs to an Indigenous tradition, which was paradoxically a culture of civilisation and development in the region of Central America. Despite his preferred pronouns, he is known as a being of balance between masculine and feminine, earth and sky, serpent and bird. He embodies the ritual knowledge of regenerative agriculture. He departed with the collapse of Toltec civilisation, but not in the same way as the gods of monotheistic religions, who pass from this realm and ascend to another world where we must strive to follow them. As with all Serpent beings that are slain or driven out, he remains in the Law and Ceremony of the living land and its people. The good thing about snake-like creator beings is that their death or departure does not take them to a different plane beyond existence: to the ultimate binary of heaven or hell. Instead, they are integrated into our world through the non-binary reality of unified opposites. In this way, there has been a Meso-American Indigenous renaissance following Spanish colonisation, one in which the lessons of empire and civilisation have been learned, and the people have returned once again to land-based ways of knowing and being. This is a path everyone must follow to halt the destruction of the earth.

South Asia

The notion of mortality and ascendance in creator beings led us to explore the fear of death with our friend Parul Punjabi Jagdish from India, who told us stories of Shiva and the sacred Serpents called Nagas. He told us that industrial civilisation separates us from nature in ways that make us think of death as a destructive termination point inspired by stories of struggle against nature as an enemy. “That is bad death,” he said. “Snake is good death.” The Nagas are associated with Shiva, the god of destruction, as regenerative and cyclic renewal. Devas and Asuras struggle as light and dark forces in the ‘churn’ of creation in land and sea, and the Naga is the binding thread within this churn that ties opposing forces together in balance.

In our Aboriginal culture, you must have the right name to call out to the ancestral spirits in a place before you enter, and Parul’s gift of the name Naga takes us across Asia for yarns with traditional craftspeople and keepers of sacred Serpent knowledge, in many places of cultural fusion between Indigenous, Hindu and Buddhist spiritualities.

Kathmandu fountains, Creative Commons from https://itoldya420.getarchive.net/amp/media/nepal-kathmandu-architecture-architecture-buildings-ece1a0

Having explored notions of dead gods and the fear of death, we next inquired about the fear of god with Anil Chitrakar in Kathmandu. Is it possible for a culture to maintain collective care of the common good without ‘fear of god’ as a motivation for ethical behaviour? Anil showed us that the carefully stewarded natural system of water collection and filtration that Kathmandu depends upon hinges on snakes as a keystone species. It is maintained as a community commons alongside a thriving street economy managed by interdependent guilds of craftspeople. A shared sense of the sacred underpins this, but it is not motivated by fear of any god; rather, collective mutual care of land and people is driven by a visceral awe of nature that is grounded in reverence for Naags.

Naags are ‘spirited snakes’, which refers to mundane reptiles transformed by an understanding of right and wrong, not just in themselves, but in the people who co-exist with them. Those who transgress risk being bitten. The people begin most rituals and events with an unusual land acknowledgement that recognises the snake population as the First People, and they are aware that without caring for the habitat of the Naags, the microclimate is compromised, and the rains they depend on for survival will not come. Water is wealth in Kathmandu, and the Naag is their protection against the tragedy of the commons.

Myanmar

Soe Yu Nwe, Naga Mae Daw Serpent(Opens in new window), glazed porcelain, gold and mother-of-pearl lustre. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery

Next, we go to Myanmar, where the Burmese python has become the Naga. We speak with ceramicist Soe Yu as we change our theme from fear of god to fear of women. Women and snakes are connected in ancient spiritual traditions, and both are reviled in the more recent monotheistic faiths that have displaced the old Lore. Soe’s sublime work captures the liminal moment of transformation of woman into dragon, providing insight into the fear of both women and snakes that pervades regimes of male power. They are connected mythically because they share the trait of extreme biological plasticity, and they are the gatekeepers of creation and destruction. Soe’s delicate, precarious work is shockingly out of place amidst the violence of the authoritarian coup and ongoing civil war instigated by Myanmar’s misogynistic regime, which is supported by Buddhist spiritual leaders who assert that one can only achieve enlightenment in a male body. Their sect believes the presence of a woman destroys the holiness of sacred objects and sites, so women are excluded from many places of worship (and leadership roles in government).

Indonesia

Snake as decoration of a railing in the Kraton of Yogyakarta (Palace of the Sultan), Java, Indonesia; photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas

We followed that same extremist sect to our final stop on the Naga songline in Indonesia, where the Chinese monks settled before extending their mission to Myanmar. We spoke with Dias Prabu, a batik artist who told us about the sacred Serpents of the First Peoples, which were later embodied by Antiboga the Naga with the arrival of Hinduism, then the Javanese Dragon with the arrival of Chinese Buddhism. Prias’ Serpent knowledge offered us deeper understanding of how cultural exchange, wealth and innovation can flourish through trading practices based on mutual benefit and good relationships rather than competition and avarice. We shared stories of the ancient trade between Indonesia and Aboriginal Australia, which he has honoured in his works exhibited here, and we also came to understand how the Serpent helps people make sense and meaning from cataclysmic natural disasters, invasions and genocides.

Above all, we learned the way Serpent entities endure but change as populations increase in scale and power. Dias said, “As soon as you have kings and larger nations, that Snake becomes something else. The Javanese dragon is more snake-like than the Chinese ones, though, holding earlier meanings of fertility, love, and protection of the earth.”

China

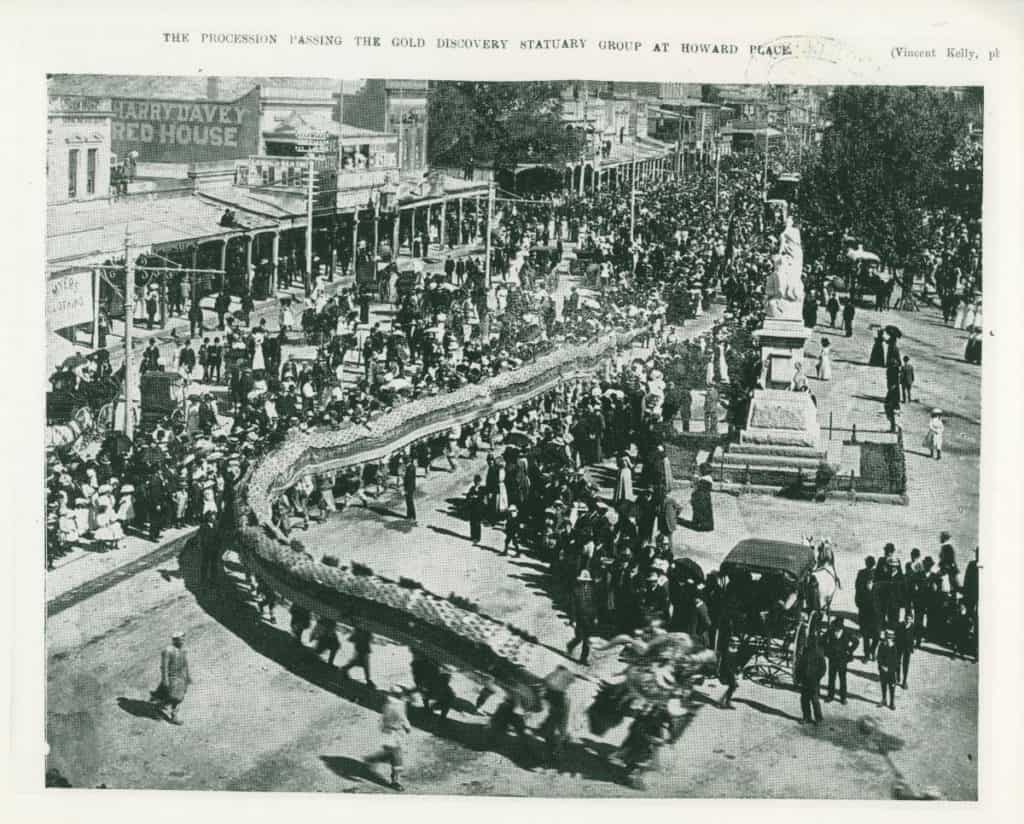

The dragon Loong in Bendigo’s Easter parade, 1911. (Collection Golden Dragon Museum. Photographer: Vincent Kelly)

The Chinese Dragon appeared throughout our travels, from remnants of the Mongol occupation of Persia to every site of our Naga journey across Asia, so next, we sought the Loong, but not in China. For thi,s we returned to Aboriginal land in Australia, specifically the quartz-rich areas of Taungurong land where Mindye the serpent dwells. When Bunjil calls on him, he brings pestilence to communities that damage the land and behave lawlessly, a job which kept him busy during the gold rush in the region, in which miners were struck with epidemics of typhoid, cholera and worse. The Chinese miners on the goldfields of Victoria fared better, however, as they had doctors, gardens and personal hygiene.

Their health and prosperity drove the miners wild, with racial hatred and violence building to the famous rebellion of Eureka, which was only settled when the government agreed to restrict Asian immigration and shift the tax burden of the miners to Chinese Australians. Federation soon followed, along with the White Australia Policy that was largely driven by moral panic over what was called ‘The Yellow Peril’. But the Chinese community, ever patient and caring neighbours, celebrated Federation alongside European settlers in processions of Imperial parading dragons.

Australia today boasts the longest and oldest Imperial dragons on the planet.

Billy Potts, an international organiser of traditional Chinese cultural revival, told us the story of the suppression of customs and arts during China’s cultural revolution when the dragon makers sought refuge in Hong Kong and Australian communities. As a result, Australia today boasts the longest and oldest Imperial dragons on the planet. The Chinese community parades them to raise funds for the building of hospitals in rural Australian communities and even to erect monuments to the fallen rebels at Eureka Stockade, while bigots sporting Southern Cross tattoos like swastikas scream about an ‘Asian invasion’.

South Africa

Andile Dyalvane, engeba (one of the clan names of ooJola): This non-traditional form has been channelled by the serpent deity. The form emerges from the coiled base as if it is rising up from a rock. This reflects the re-birth / re-surfacing of identity that was erased by the oppressors.

In this yarn, we began to see the spirit of the Serpent as connective, moving across the invisible borders of geo-political power struggles and making embassy everywhere the Lore of great Snakes is remembered. He travels with the people who hold his sacred knowledge, making new homes with them. Following the trail of the Snake in diaspora, we journeyed to post-Apartheid South Africa.

Xhosa sculptor Andile Dyavalne told us stories of his clan, which originally came from a village on the Eastern Cape, but was forcibly removed to prison camps when their land was stolen, then later the survivors migrated to the city. They were converted to Christianity, their old customs were forbidden, and no written records were ever made of their former ritual practices and spiritual beliefs. But his clan’s totemic Snake entity, ooJola, followed them to the city and has helped them regain their language and cultural knowledge.

This process of cultural recovery involves hearing ‘whispers’ and dreams from the ancestors through ooJola, then submitting these for analysis by Elders with all the community as witnesses. Everybody has different cultural vocations, as makers, musicians, dancers and so forth, and they all carry those spiritual messages into their work in preparation for Ceremony. After the Ceremony, the connection is increased and each clan member is open to more whispers from the ooJola and the ancients, which are shared with all in ways that gradually cohere into cultural narratives and customs that have ancestral continuity in spirit.

Dyalvane shows us three clay sculptures revealing different aspects of ooJola that depict the stages of this process: the seed of the message as it is whispered, the affirmation of the message finding its rightful place with his people, and the remembrance of who they are in a repositioned reality beyond displacement. Andile asserts that even if Elon Musk moves his community to a colony on Mars, the customs of his clan will endure because ooJola will follow them there.

Ireland

But is the recovery of land-based traditions in diaspora only available to people from the global south? Seeking hope for our European cousins in the path of the Serpent, we sit with Irish Lore-keepers and yarn with Manchan Magan and Lydia Campbell to find that the spirit of the Snake was certainly never extinguished by St Patrick and that First Nations culture is alive and well in Ireland.

On that mystical green isle, the Wyrm is present in most bodies of freshwater and frequently travels along waterways and beneath ground, moving between over 3000 wells and springs that represent the vaginal openings of the matron of the earth, reflected in the native words for all bodies of water, which are named after female reproductive organs. Seasonal Ceremonies are still held at many sacred wells, where people await the arrival of eels in the well, which are regarded as manifestations of the Wyrm and his blessing. In folk medicine still practised today, a complicated knot representing the Wyrm’s tortured body is made with a string or rope, then placed over the afflicted area, and if it is made properly, it comes undone when both ends are tugged, pulling the illness from the patient.

There are Serpent-slayers in Irish Lore, but these are usually cautionary tales about men seeking to usurp the feminine power of nature. In one of these tales, the apex female deity of Ireland, known as ‘the Hag’, is attacked by princely heroes, and she brings forth the Wyrm to wreak havoc across the land. The famous Shannon River is a reminder of this Law, as it was formed by a Wyrm that was banished by heroes reacting to their fear of Woman and Snake. The river is known as a living Lore text, a pathway of knowledge and enlightenment placed there by the Serpent (what we in Aboriginal Australia call a songline).

Ecuador

The Wyrm and the Hag move across multiple dimensions in the Indigenous conception of place-time, transforming into different bodies and characters with the change of the seasons while also traversing three layers of creation spanned by the Celtic tree of life. We found a similar metaphysical matrix of space and seasonal time in Ecuador when we yarned with Nkwi Flores from Kara Kichwa First Peoples.

Ahmaru is the Serpent there, who crosses four layers of reality. The land is sentient, and so it has a psychology – the surface is Hanan, the personality and character; the sky is Hanank, which is like the ego and superego; the subterranean world is Uhku, which is like the subconscious; and finally there is Uhrin, the unconscious, the deep dark of the cosmos that came before creation. That is where Ahmaru lives, and when you do Ceremony, you have to enter that space while still remaining conscious, which is quite a feat.

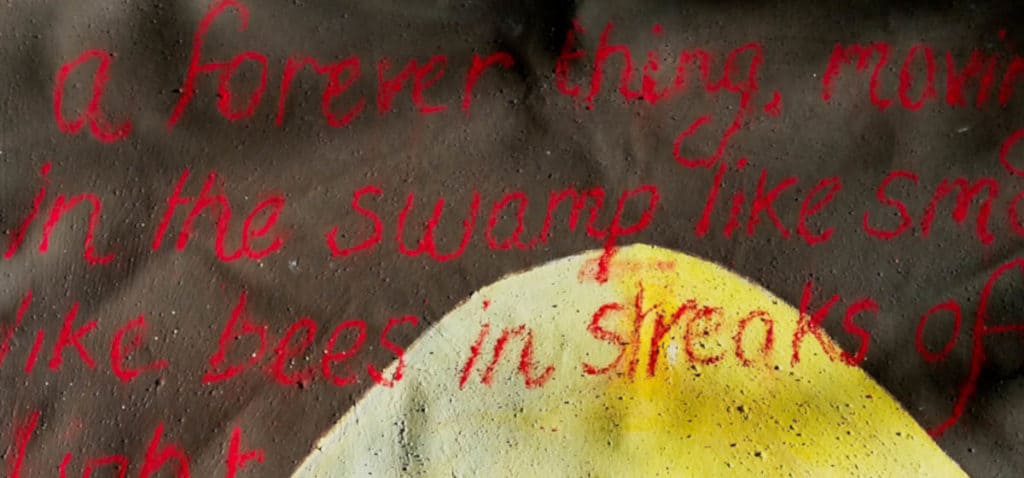

The image of Ahmaru looks like an infinity symbol but in the elaborate diamond and zig-zag patterning of Andean aesthetics. In the centre of the symbol, you are dying and being born, celebrating and mourning. Two heads of the Serpent emerge, symbolising the duality of the warlike feathered Serpent in his season and the nurturing scaled Snake caring for all during the planting and harvest season.

The martial face of Ahmaru emerges from the warrior dance Ceremony that is performed during the summer solstice, in which he transforms into the feathered serpent. Here, he takes to the sky to inhabit the psychological ego of the earth. In this form today, he has become a symbol of anti-colonial resistance, but there are problems with remaining in this warrior state in every season, as nurturance and relatedness become stifled. As Indigenous people, we all face this problem – we must be winter soldiers in the struggle for self-determination and protection of our land because the invader never sleeps.

Unfortunately, those of us who fight to keep the old ways and assert our sovereignty must often construct defensive borders around our territories and identities in denial of the flows of land and time. We sever the connective Law of the Serpent when we fight fire with fire in this way. But then, if we don’t do this, we are burnt out and destroyed. We must extend our hands to others if we want to survive, but when we do this we risk losing our arms.

So how can all the diverse cultures of the world recover trust and trustworthiness simultaneously, rebuilding an interdependent, collective reality in the path of the Snake? We have gathered some wisdom to address this question in our journeys, but to learn about those, you will have to wait for the book.

This story is drawn from Megan Kelleher & Tyson Yunkaporta, Snake Talk: How the World’s Ancient Serpent Stories Can Guide Us, published by Text in 2025. Garland authors in this journey include Andile Dyalvane, Antonio Arico, Dias Prabu, Jamnalal, Linda McIntosh, Tiao Nith. Thanks also to Anil Chitrakar, Eduardo Aguilar Zarandona, and Nargues Teimoury. See also Garland’s stories about eels.

This story is drawn from Megan Kelleher & Tyson Yunkaporta, Snake Talk: How the World’s Ancient Serpent Stories Can Guide Us, published by Text in 2025. Garland authors in this journey include Andile Dyalvane, Antonio Arico, Dias Prabu, Jamnalal, Linda McIntosh, Tiao Nith. Thanks also to Anil Chitrakar, Eduardo Aguilar Zarandona, and Nargues Teimoury. See also Garland’s stories about eels.

About Tyson Yunkaporta

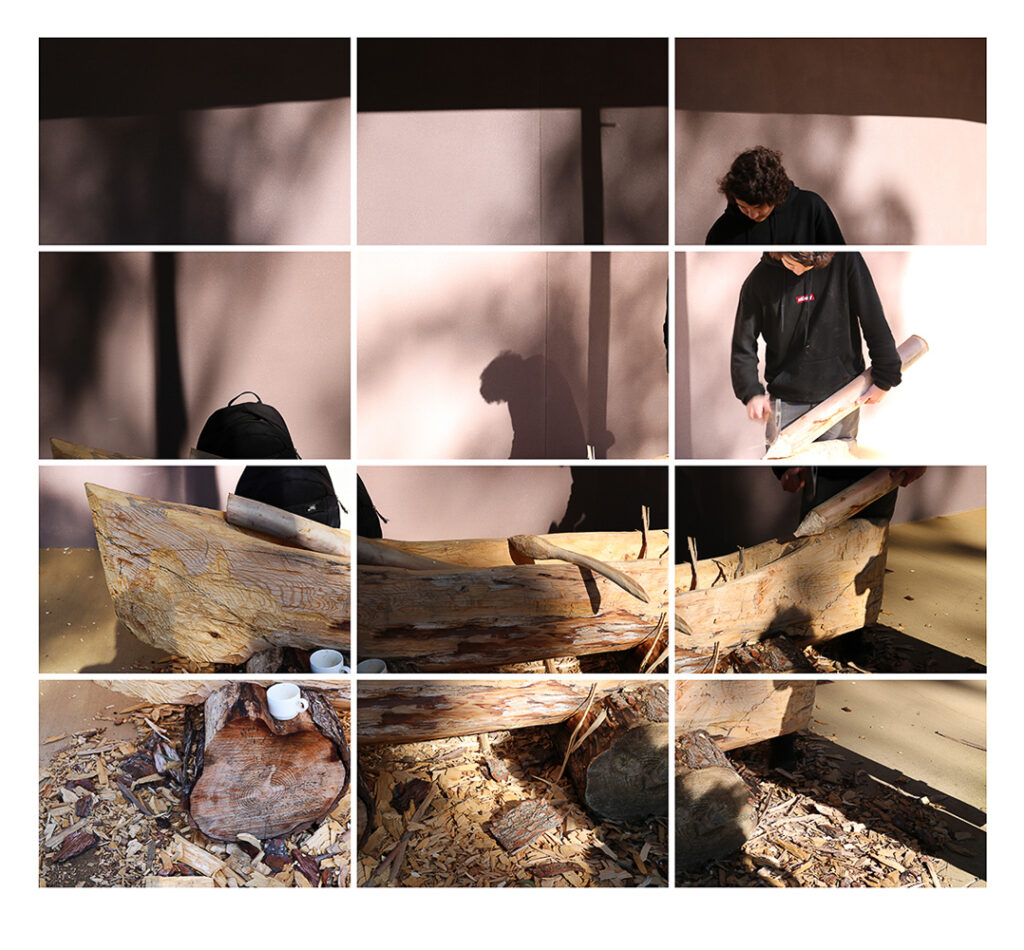

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, arts critic, and researcher from the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He is a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne and founded the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab. Yunkaporta is known for his work in applying Indigenous perspectives to address global issues, as seen in his books Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World and Right Story, Wrong Story: Adventures in Indigenous Thinking. He also carves traditional tools and weapons, reflecting his deep connection to Indigenous culture. His approach emphasises the importance of collective thinking and deep time perspectives, challenging conventional views on knowledge and the world. Listen to The Other Others.

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, arts critic, and researcher from the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He is a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne and founded the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab. Yunkaporta is known for his work in applying Indigenous perspectives to address global issues, as seen in his books Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World and Right Story, Wrong Story: Adventures in Indigenous Thinking. He also carves traditional tools and weapons, reflecting his deep connection to Indigenous culture. His approach emphasises the importance of collective thinking and deep time perspectives, challenging conventional views on knowledge and the world. Listen to The Other Others.

See also

Snake Talk: A yarn with story-makers across the globe - Tyson Yunkaporta reflects on the fluid connections made by serpent beings between peoples and nature.

Snake Talk: A yarn with story-makers across the globe - Tyson Yunkaporta reflects on the fluid connections made by serpent beings between peoples and nature. Humans as a custodial species - Tyson Yunkaporta explains how humans became a custodial species and their role to increase the connections within the world.

Humans as a custodial species - Tyson Yunkaporta explains how humans became a custodial species and their role to increase the connections within the world.  Thinker maker: Tyson Yunkaporta on 31 March - To launch the March issue of Garland, Tyson Yunkaporta and other thinker-makers across the wider world yarn about humans as custodial species.

Thinker maker: Tyson Yunkaporta on 31 March - To launch the March issue of Garland, Tyson Yunkaporta and other thinker-makers across the wider world yarn about humans as custodial species. He stood up! ✿ Winds of change at the Ancient Now symposium - The Ancient Now symposium heralded not only new creative pathways to China, but also a changing world view inspired by the dragons among us.

He stood up! ✿ Winds of change at the Ancient Now symposium - The Ancient Now symposium heralded not only new creative pathways to China, but also a changing world view inspired by the dragons among us. A rainbow serpent theory of time - For Tyson Yunkaporta, the rainbow serpent offers an alternative to the circular world of second peoples.

A rainbow serpent theory of time - For Tyson Yunkaporta, the rainbow serpent offers an alternative to the circular world of second peoples.