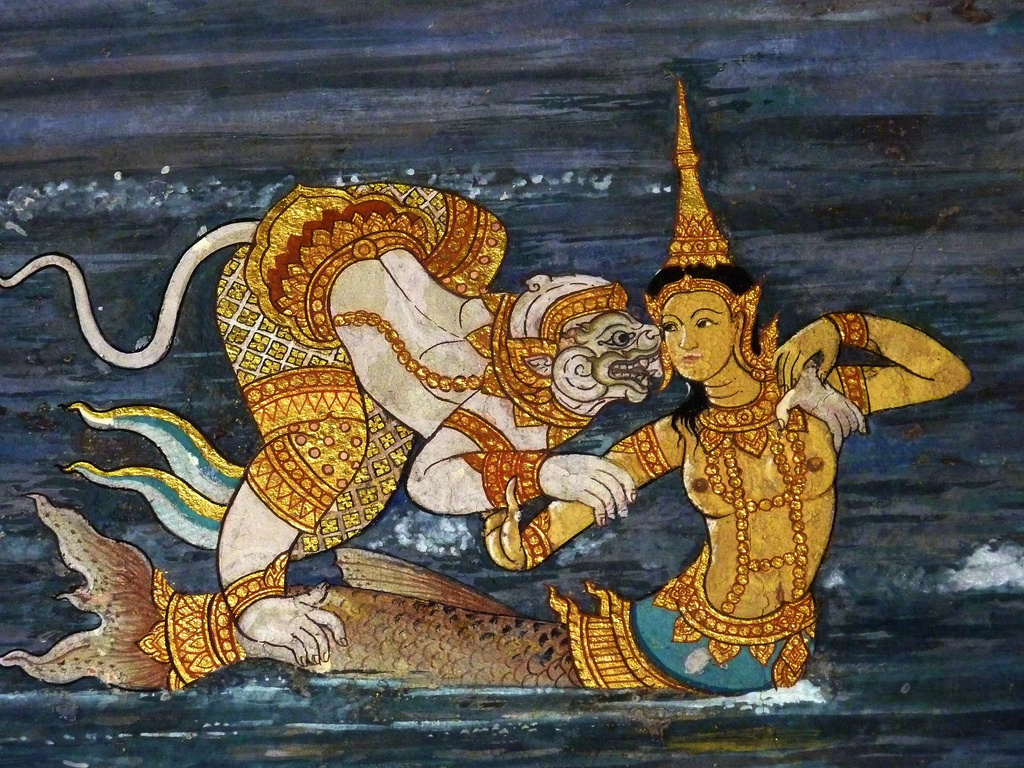

Detail, A mural painting of Suvannamaccha and Hanuman at Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chandrica Barua recounts the story of Suvannamaccha, the Golden Mermaid, who appears in Southeast Asian depictions of the Ramayana.

The story of Hanuman falling in love underwater with the mermaid daughter of Ravana, the demon king of Lanka, is not a tale one would encounter in Valmiki’s Ramayana. In Southeast Asia though, it is a much beloved story told and retold over many generations.

Unlike the proliferation of mer-people as fantastical creatures in folklore and mythological traditions of other cultures, Suvannamaccha—Suvarnamatsya in Sanskrit—the Golden Mermaid is perhaps a rare example in our storytelling oeuvre. While fantastical aquatic creatures are scarce in traditional Indian mythology, the concept isn’t entirely absent. Vishnu’s avatars, Matsya (fish) and Kurma (tortoise), showcase a rich imagination associated with water beings. Suvannamaccha, the Golden Mermaid, is a distinct addition woven into the Ramayana tapestry of Southeast Asia, particularly prominent in Reamker, Cambodia’s epic poem and Ramakien, Thailand’s national epic.

The story unfolds as Hanuman, the valiant monkey god in Hinduism, and his vanara army of anthropomorphic monkeys embark on the monumental task of building a bridge to Lanka to help Rama rescue his wife, Sita, from the clutches of Ravana. With the rocks mysteriously disappearing the next day, Hanuman dives down to the depths of the sea and encounters a band of mermaids stealing the rocks, led by the mesmerizing Suvannamaccha. He launches repeated attacks on her but she manages to evade him every time, and over the course of this battle, Hanuman falls in love with her. He abandons his forceful approach and showers her with tenderness instead of attacks until she, too, returns his love, and they spend a blissful period underwater.

Hanuman overcomes Suvan Maccha, Traditional Cambodian Dance Show, Golden Mermaid Dance, c. 2016. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

One day, Hanuman questions Suvannamaccha’s motive for hindering the bridge construction. She reveals she was acting on her father Ravana’s orders. Upon learning the true purpose of the bridge from Hanuman, Suvannamaccha has a change of heart, and she promises to return all of the stolen rocks. She also gives birth to Hanuman’s son, Macchanu, a character missing from Valmiki’s Ramayana. With a vanara’s torso and the lower body of a fish, Macchanu opposes Hanumanu later during a battle with Ravana’s army. Interestingly, in Valmiki’s Ramayana, Hanuman has a son named Makaradhwaja, born out of his sweat, as Valmiki’s Hanuman remained celibate for eternity.

Thai folk dance of the Ramayana in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Photograph: Evan Silver(2017), Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Several murals, Thai silk paintings, illustrations, sepia paper art, sculptures and even paper and cloth charms depict the mermaid daughter of Ravana (Thotsakan in Thai) entangled in amorous embraces with Hanuman. The widely popular Southeast Asian legend is also performed as Robam Sovann Maccha, a traditional Cambodian dance. Dated to the seventh century, it was performed as a temple ritual during the Angkor period and is a famous piece in the repertoire of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia today.

This curious reimagination of the celibate Hanuman as a passionate lover reminds us that as cultural, religious and social beliefs and practices traverse the porous boundaries between different regions, we are gifted with a whole world of imagination, retellings and new stories. It serves as a testament to the transformative power of cultural exchange.

Mermaid Suvannamaccha with Her Husband Hanuman, Khmer empire, Cambodia, c. 14th century, Sandstone, 52.1 x 50.8 x 11.4 cm, Image courtesy of Birmingham Museum of Art

Further reading

Brandon, Banham, James R., Martin. The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Desai, S.N. Hinduism in Thai Life. New Delhi: Yash Publications, 2006.

About Chandrica Barua

Chandrica Barua is a PhD candidate in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where she is writing a dissertation on nineteenth and twentieth-century plantation literary cultures. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Victorian Review, CUSP: Late 19th-/ Early 20th-Century Cultures, Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens (Victorian and Edwardian Notebooks), and Feminist Review. She was formerly Nonfiction Editor for Michigan Quarterly Review and Research Editor for MAP Academy, India. She is from Jorhat, Assam.

Chandrica Barua is a PhD candidate in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where she is writing a dissertation on nineteenth and twentieth-century plantation literary cultures. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Victorian Review, CUSP: Late 19th-/ Early 20th-Century Cultures, Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens (Victorian and Edwardian Notebooks), and Feminist Review. She was formerly Nonfiction Editor for Michigan Quarterly Review and Research Editor for MAP Academy, India. She is from Jorhat, Assam.

About MAP Academy

The MAP Academy is an open-access online resource focused on South Asian art and cultural histories.