LOkesh Ghai discovers the authentic incense of the Gaddi nomadic community, redolent of the land they traverse.

Treading the same path again and again with an inquisitive mind, a deeper insight is gained about how to adapt to the ways of the environment. An awareness of nature encountered on the path leads to many craft narratives. One such encounter with flora by the Gaddi community would have led to the invention of dhoop-batti. Dhoop-batti is an earthy incense with a thick and rich aroma, that accompanies prayers across the Indian sub-continent. The Gaddi version of this fragrance is unique.

Gaddis are the semi-nomadic community of Himachal Pradesh who migrate across the mountains to find green pastures for their sheep and goats. According to one of the beliefs, they were given their name because they are close to the Gaddi (seat) of Lord Shiva. The ancient town of Bharmour, home to the Chaurasi temple housing eighty-four Shiv-lings, is central to Gaddis.

In the suburbs of Bharmour is Dheeraj Singh’s house. Like many other Gaddi houses, every morning and evening before the meals, a specific ritual is practised. He prays to Lord Shiva in the humble shrine that overlooks the kitchen. A dhoop-batti is lit up with his right hand, as he rings the bell with his left hand, alternating it with the ringing of the damru, the power drum associated with Lord Shiva. The dhoop-batti is placed on the aarti lamp and is offered to the idol of Shiva and the associated Gods. The fragrance of the dhoop-batti evokes all the senses.

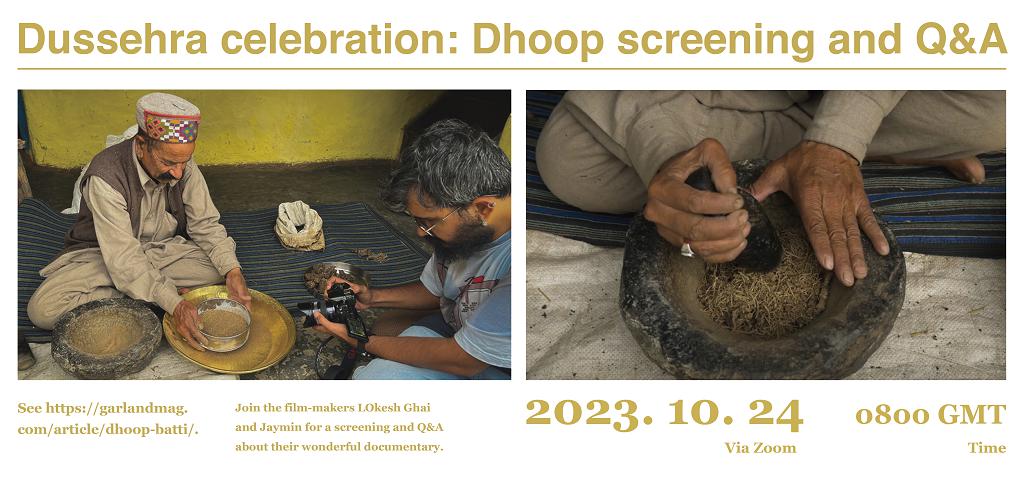

I had purchased a package of locally made dhoop-batti from a general store near the Chaurasi temple for sixty rupees. Responding to my purchase, Dheeraj ji offered to demonstrate the making of the dhoop-batti at home. When he still had a flock of sheep some thirty years ago, he used to travel with them; he did this for fifteen years.

It is during this migration that the shepherds used to come across the plant locally known as “dhoop”. Though there are artificial imitations, the original dhoop is derived from the plant, hence the name.

When the snow melts at higher altitudes, the sheep are taken to graze on the new green slopes, which is where many plants unique to the landscape grow. The shepherds could then source the dhoop for making fragrance for domestic use. While a few years ago the shepherds could freely obtain the plant from the earth, now permission is required from the Forest Department. Nowadays, the few Gaddi who still make the dhoop-batti purchase the plant roots from the shepherds.

The roots of the dhoop are dried in the sun before being pounded in a kund, a container made by carving local rock. The two tools used for pounding are batta, a smoothened elongated oval made from the local rock, and danda, a beautifully carved long stick of bun tree wood. The container and both the tools were made by the artist some twenty-five years ago and since then have been used in the kitchen. The roots of the dhoop are pounded again and again with the help of batta until the dryness disappears making it sticky. The flattened extract is pounded further in layers, resulting in a lump that is stumped again. By pounding the lump myself, I realized both through observation and by the touch of the tool, when it starts getting sticky, it is understood to be ready.

The second key ingredient is nihani, which has a thicker root with further hairy roots protruding from the main root. It has a beautiful aroma. A bunch of roots are first crushed, then ground resulting in a dry powder. The powder is stained with a hint of coal and a finer residue is achieved mixed with the thick lump.

A generous spoonful of desi-ghee is added to the container. With the help of the wooden danda, the mix is again repeatedly pounded in the container. Finally, a black dough is achieved. This is rolled to make ladoo-like portions.

Finally, the dough is rolled on a smooth wooden plank to make a long cylinder that is wrapped in recycled newspaper. They have roughly the same weight and even shape, perfect for selling at local shops. A brand name is printed manually on paper is pasted on the wrapper package using gum made from rice water. Usually, local makers use devotional or regional names, such as Mahamaya. As a quality control measure, while the final dough is being rolled, any tick grains found are removed. The sales of dhoop-batti are regular in small quantities, mostly for local consumption. However, there is a jump in sales during the pilgrimage time of Mani-Mahesh Yatra and the Navratri festival.

The dhoop plant has medicinal properties and is considered sacred. Whether for domestic or commercial making, shoes are not worn while making the dhoop-batti as a sign of respect to God and to maintain purity.

Before every prayer time, a small portion of the dough is pinched from the larger lump available. The small portion is rolled by hand, thick or thin, big or small as desired, and installed at the shrine on the aarti plate. The dough stands by itself and gradually its smoke rises, evoking the Gods and the human senses.

Scientific names:

- Bun- Quercus leucotrichophora

- Dhoop- Jurinea Dolomiaea

- Nihani- Valeriana Jatamansi

About LOkesh Ghai

LOkesh Ghai is a design educator and researcher working with traditional craft practices and communities. He is interested in the cultural-making of craft and clothing. He has showcased his textile art at the Museum of Childhood, London. As a designer and associate curator, he presented India-Street exhibition in Scotland; the show was a runner-up for the most sustainable design practice award. He is a design faculty at UPES, Dehradun, he has been a founding faculty at Somaiya Kala Vidya, Kutch, India’s premier design institute for traditional craft communities. In 2022, Ghai won The Karun Thakar Fund, by the V&A Museum, London; his research focuses on tailoring as a heritage. He has recently been awarded a research grant from Indian Foundation for Arts to work with the heritage of shoemakers in Dehradun Valley. Follow @ghailokesh

LOkesh Ghai is a design educator and researcher working with traditional craft practices and communities. He is interested in the cultural-making of craft and clothing. He has showcased his textile art at the Museum of Childhood, London. As a designer and associate curator, he presented India-Street exhibition in Scotland; the show was a runner-up for the most sustainable design practice award. He is a design faculty at UPES, Dehradun, he has been a founding faculty at Somaiya Kala Vidya, Kutch, India’s premier design institute for traditional craft communities. In 2022, Ghai won The Karun Thakar Fund, by the V&A Museum, London; his research focuses on tailoring as a heritage. He has recently been awarded a research grant from Indian Foundation for Arts to work with the heritage of shoemakers in Dehradun Valley. Follow @ghailokesh

About Jaymin

Jaymin is a filmmaker based out of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. He primarily works for the Gujarati film industry. He learned filmmaking at National Institute at Design, Ahmedabad, which grants him a unique ability to see filmmaking as a design process. Which reflects in his work such as a craft documentary he made on Ajrakh, a block printing craft from Kutch, Gujarat, India. He helms multiple departments while working on a film, according to him it brings a synergy between various processes that results into a unified seamless film.Visit www.behance.net/jmthefilmmaker Follow @jaymineonoir

Jaymin is a filmmaker based out of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. He primarily works for the Gujarati film industry. He learned filmmaking at National Institute at Design, Ahmedabad, which grants him a unique ability to see filmmaking as a design process. Which reflects in his work such as a craft documentary he made on Ajrakh, a block printing craft from Kutch, Gujarat, India. He helms multiple departments while working on a film, according to him it brings a synergy between various processes that results into a unified seamless film.Visit www.behance.net/jmthefilmmaker Follow @jaymineonoir

Register for a special Dussehra screening of this film with Q&A on 24 October here.

Register for a special Dussehra screening of this film with Q&A on 24 October here.

Comments

Very insightful article! Love how wholesome the video made me feel, very pious <3

Wow, I didn’t even know this is how the original dhoop is made. Looks like a disappearing craft. I wonder if the dhoop plant is in any kind of danger of extinction since it’s being protected by the forest department. And I wonder how many such uses of plants have been lost to time. Thanks for documenting this so beautifully.

An insightful read !

Lovely film. Great work Jaymin 🙂

Great project. Beautifully framed shots and skilfully edited with a wonderful soundtrack

Lokesh loved the video – simple and to the point and ur writing tops all, new learning for me as well.. will wait for many more similar articles