Plate Recorder, Liat Segal and Roy Maayan, 2017; Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, ceramics, overglaze; plates: 30×30 cm

Liat Segal presents three bodies of work that use randomness as a creative tool.

Artists and scientists aren’t so different. Both scientists and artists observe the world, ask questions and search for truth. Both are motivated by curiosity and a burning inner call. Both observe their subjects through their personal, unique prisms and ask questions about them. The artistic process, much like the scientific one, grows from an inner seed that germinates in its creator’s mind. Then comes observation, distillation, research and experimentation. Both artists and scientists cherish the value of mindfulness and persistence on one hand, and of exploration and risk-taking on the other.

The scientific method can be seen as an evolutionary process of ideas, aiming to accurately describe nature. Scientists transform hypotheses into theories, just to have these theories disproven, followed by new and hopefully more accurate hypotheses. Artists transform raw materials, whether physical or mental, into concepts and emotions, aspiring to touch hearts and minds. In this sense, as in the practice of the alchemist, both distil ideas and, metaphorically, transform lead and copper into silver and gold.

It is a common conception that scientists must be accurate and control-oriented, while artists are culturally regarded as free-spirited explorers. It may come as a surprise that in the case of many great works of art and science, the special ingredient in the work process is randomness and serendipity. The process of scientific investigation involves answering questions, but more importantly, it requires asking the right questions in the first place. Randomness and serendipity are sometimes the fairy dust that ignites innovative works of art and science, leading to fresh perspectives and imaginative ideas.

Examples of serendipitous scientific discoveries, apocryphal or not, are ubiquitous. Archimedes takes a bath and realizes that, “Eureka!”, the more his body sinks into the water, the more water is displaced, i.e. the displaced water is an exact measure of his volume. An apple hits Isaac Newton’s head, leading to the realization that the same force that made the apple fall downwards also keeps the Moon falling toward the Earth and the Earth falling toward the Sun, namely gravity. After being away from his lab for a month, bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to find that his bacterial cultures had been contaminated and destroyed by a fungus. In many labs prior to that day, bacterial cultures had been contaminated and thrown into the garbage, but Fleming identified the potential. The discovery of penicillin occurred due to a flow of accidental events and thanks to Fleming’s attention, observation and ability to catch the chance.

Being an artist who comes from a scientific background, much of my way of thinking, materials and toolbox are influenced by science and technology. My artworks consist of several dimensions: a physical structure, mechanics, electronics, software, and data. I am interested in human existence in an age of Big Data and accelerated technological advances and ask questions about intimacy vs. alienation, control, free will, identity, memory, presence, and communication.

Random Walk

- Random Walk: Effect and Ripple, Installation, Liat Segal, 2019, Effect: Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, TPU tape, brass, ropes 200x200x320 cm, Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, aluminium, glasses, water, magnets, 200x200x60 cm; photo: Liat Segal

- Liat Segal, Random Walk, coin tossing machine

My exhibition Random Walk (Artist’s Residence Herzliya, Israel, 2019; curator: Ran Kasmy-Ilan) put randomness in the spotlight and dealt with the amount of control we have over our lives and our degree of free will. In this exhibition, I observed randomness and used it as a material.

In a world so overwhelmingly complex, we tend to make simplifications that enable us to view our lives as a series of logical steps and choices. As if the world comprises a clear set of causes and effects and of absolute truths, rather than chaos. The exhibition took its name from the mathematical concept of the Random Walk, which describes random processes over time. There were three parts: Cause, Effect and Ripple, with three machines that made this random process tangible with form.

Cause, the starting point, was a coin-tossing machine. A large metal cylinder positioned as an altar has a stretched piece of black latex at its head. A coin that rests on the sheet is tossed by an internal mechanism every few seconds. The result of each toss was recorded by a camera positioned above the cylinder. It was displayed in binary values on an electronic screen, updated every few seconds. In Effect, the results of the coin’s continuous tossing affect the second component. A large cone composed of 1,165 narrow black elastic bands, which burst off the gallery wall, extended towards a point in the centre of the space. This beast-like object hovered in the air, held by two mechanical belts that pulled the cone sideways, according to the coin-tossing outcomes. In Ripple, hundreds of clear cups, half-filled with water, were placed on a round metal dais. They were positioned upside down; their rims rested on the surface. Each glass contained a tiny magnet that could be moved by a magnetic mechanism hidden under the surface, selectively making waves within the glasses. Motion in the gallery space, including that of the large cone, was recorded by another camera. When the motion was detected, it triggered the ripples inside the glasses, agitating the water and then dropping still, awaiting the next call.

- Random Walk 2.0, Liat Segal, 2019, Painting machine at the artist’s studio; Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, acrylic ink, paper; Machine: 120x120x30 cm; Paintings: 100×100 cm; photo: Liat Segal

- Random Walk 2.0, Liat Segal, 2019, Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, acrylic ink, paper; Paintings: 100×100 cm; photo: Liat Segal

I continued exploring randomness and free will through a painting series called Random Walk 2.0, for which I built a large painting machine that painted with ink on paper according to an algorithm and data. The painting machine visualised computational simulations of random walks. At each such process, a virtual agent flipped a simulated coin, affecting its following steps. The complex trajectories were then drawn until the agent reached its goal.

Plate Recorder

- Plate Recorder, Liat Segal and Roy Maayan, 2017; Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, ceramics, overglaze; plates: 30×30 cm

- Plate Recorder, Liat Segal and Roy Maayan, 2017; Technique: electronics, software, mechanics, ceramics, overglaze; plates: 30×30 cm

Another example, “Plate Recorder”, was created in collaboration with ceramic artist Roy Maayan. “Plate Recorder” is a digital-era homage to analog, translating sound into matter. Sounds were collected, tagged, and categorised, along with the stories underlying them. A custom-built machine etched the sound waves off fresh overglaze, covering ready-made ceramic plates, and creating ceramic plate records.

In contrast to industrial vinyl records, the recording process is not optimizing audio quality and precision. This process of translation is quite opaque as lines may overlap, the liquid overglaze flows, and environmental noise is welcomed. While recording each sound one can change the machine’s sensitivity and pace via dials and buttons, adding a subjective viewpoint to the visual interpretation.

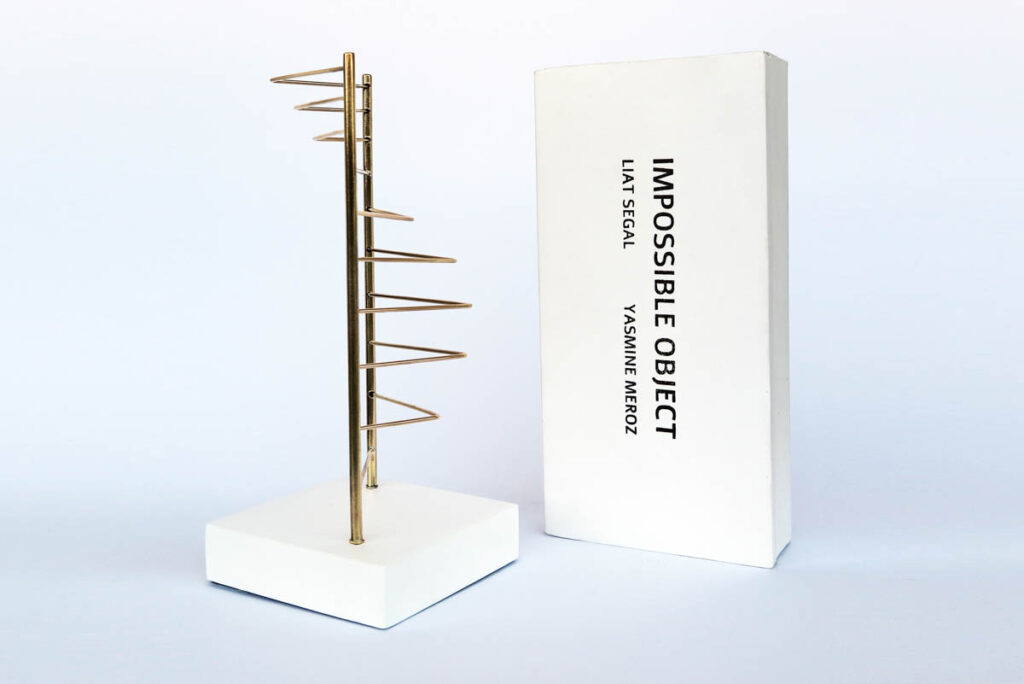

Impossible Object

- Impossible Object, Liat Segal and Yasmine Meroz, 2022; Technique: brass, aluminum, water, micro-gravity; Plates: 12x12x25 cm; photo: Liat Segal

- Impossible Object, Liat Segal and Yasmine Meroz, 2022; Technique: brass, aluminum, water, micro-gravity; plates: 12x12x25 cm; photo: Eitan Stibbe, as part of Rakia Art Mission, Ramon Foundation

My recent artwork, “Impossible Object”, is a quintessential art-science collaboration. It was created as a joint work with scientist Dr Yasmine Meroz, a researcher at Tel Aviv University who studies behaviors in plants. “Impossible Object” was sent to the International Space Station (ISS) in April 2022, as part of Rakia’s Art Mission, an initiative that seeks to capture the essence of humanity through the medium of Outer Space. It was operated by astronaut Eitan Stibe during mission AX-1, the first private astronaut mission onboard the ISS.

“Impossible Object” is a sculpture made of liquid water, whose three-dimensional form does not get its shape from any vessel, and as such cannot exist on Earth, but only in Outer Space in the absence of gravity. This work is experimental by nature, as we, its creators, could never actually test it and observe its full form on Earth, before sending it away to space. The structure of the sculpture, built as a composition of brass rods and tubes, was connected to an astronaut water drinking bag onboard the ISS. As the astronaut squeezed the water bag, water flowed through the tubes and out through small holes. With no gravitation to direct the water downwards, the water formed a dynamic three-dimensional liquid composition, shaped by the interplay between water surface tension, and its adhesion to the structure.

“Impossible Object” is a first-of-its-kind artistic experiment in Outer Space. Its outcomes were a surprise even to us, its creators. We had to welcome the loss of control and were fascinated by the unexpected outcomes, that ended up opening new scientific research ideas and artistic exploration trajectories.

About Liat Segal

Liat Segal is a contemporary media artist who fuses together art, science and technology. Segal observes human existence in an age of Big Data and asks questions about intimacy versus alienation, control, identity, memory, presence, and communication. Segal’s artworks have been exhibited in museums and galleries worldwide. In her art practice, she is materializing the digital, using software, electronics, mechanics, and information as materials. Segal is the recipient of the Minister of Culture and Sports Award for Plastic Arts, 2019, Israel. Visit www.liatsegal.com and follow @liatsegal.