For her FLOAT residency, Josephine Jakobi makes work about and with the estuary.

Bung Yarnda is an estuary in East Gippsland. I was born here, and have lived my life close to the waters and forests of this place, as did my parents and generations of grandparents. The cycles of this estuary are dependent on rainfall. When there is plenty of water in the catchment the levels rise, eventually opening the berm to the sea. In times of drought, it stays closed, sometimes for years. The cycle is complex and irregular, with salinity levels fluctuating radically.

The cycles are also of life and death. Each radical change in the water levels and the salinity results in the death of the creatures that depend on one extreme or the other, depositing layers of calcium carbonate on the floor and shore of the estuary. The plant communities are rich in species that seek out the calcium, making it available to the fauna that browse on the leaves. It is a cycle of deep time.

- FLOAT Studio residence on Bung Yarnda. (Lake Tyers)

- FLOAT in the morning mist.

I came up with a plan to record visual evidence of the changes by suspending canvas in the water at various locations around the lake. It’s a fascinating process. The canvas that I have just completed was suspended vertically in the quiet place in a little side arm. There had been some very welcome rainfall after a five-year drought and Bung Yarnda had opened to the sea, so there was a flush of new life in the water.

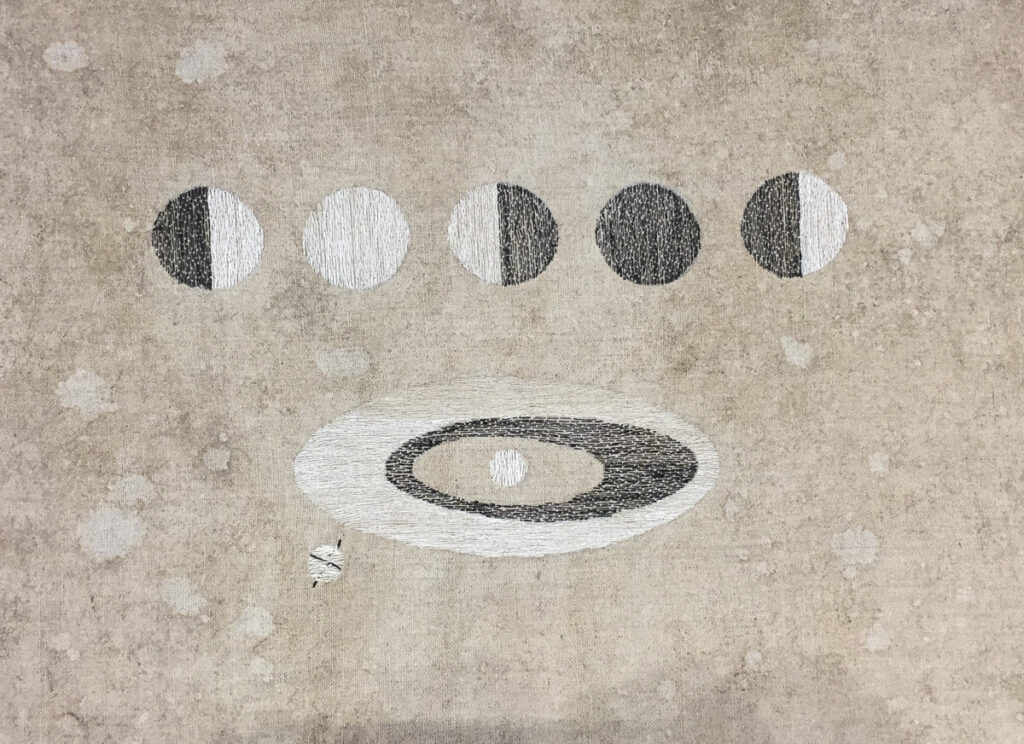

Art is a process of decision making. The choice of materials is the first step. I chose Belgian linen because of its plant origins; an acknowledgement of plants as the basis for all life. It is also a material that is produced for artists. I could have chosen cotton canvas for the same reasons, but my experiments have shown me that cotton is best used for horizontal immersion, whereas linen is best for vertical suspension. Choosing to offer the fabric to the living water allows the estuary to make the first marks on the virgin surface, giving me something that I can respond to. I leave the fabric in the water for one month; long enough to take on permanent changes, not so long that the fibres break down. One month. One lunar cycle. A recordable measure of time that is relevant to water. When the fabric is retrieved and dried, I stitch the lunar phases into the cloth. A symbol of the Earth’s journey around the Sun is also stitched into the fabric, so it becomes a record of time and place.

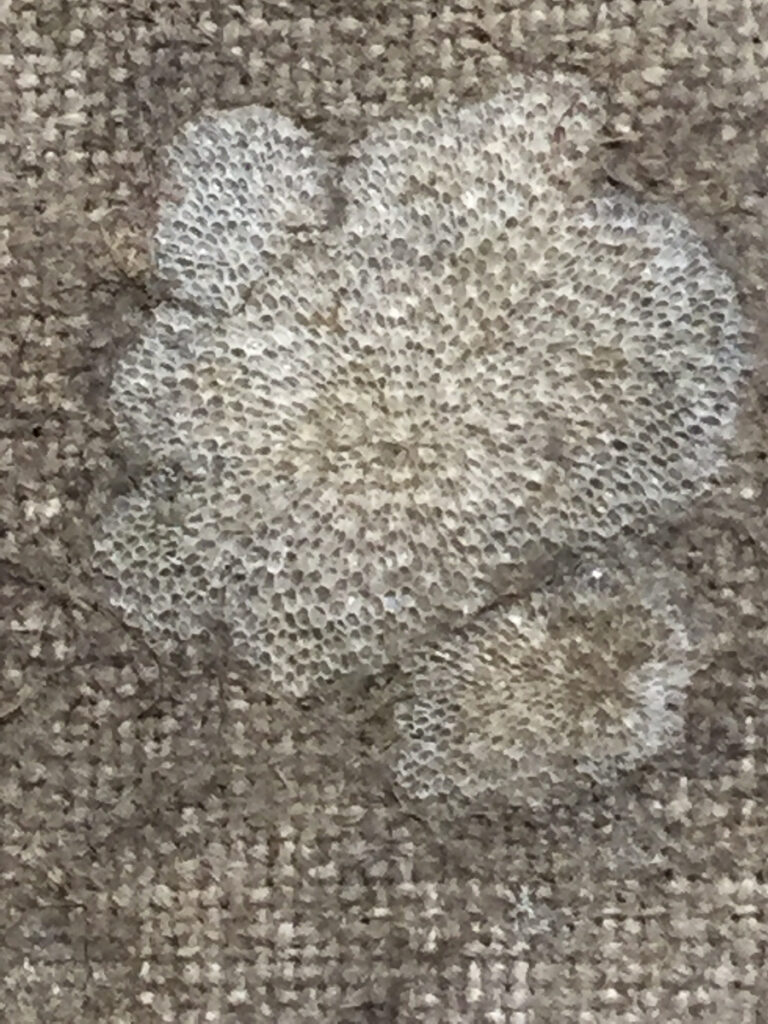

When this particular piece emerged, it had tiny patterns of calcite scattered all over its surface. When I examined these through a magnifying lens I could see a structure of tiny hexagons, arranged in lines. Intrigued as to what manner of creature had made these exquisitely delicate patterns, I searched for answers. As near as I can find, these are made by Encrusting Bryozoa, minute colonisers of surfaces in seawater. Not exactly coral, but akin to those wonderful collaborators.

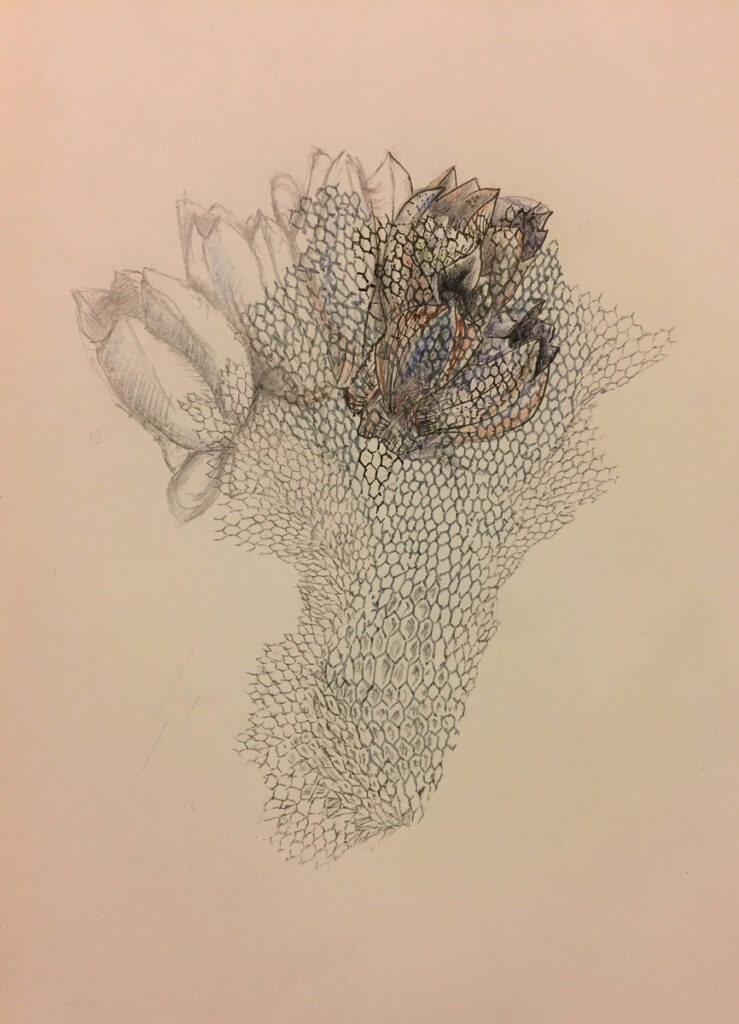

- Journal sketch. Encrusting Bryozoa.

- Stitching in Time.

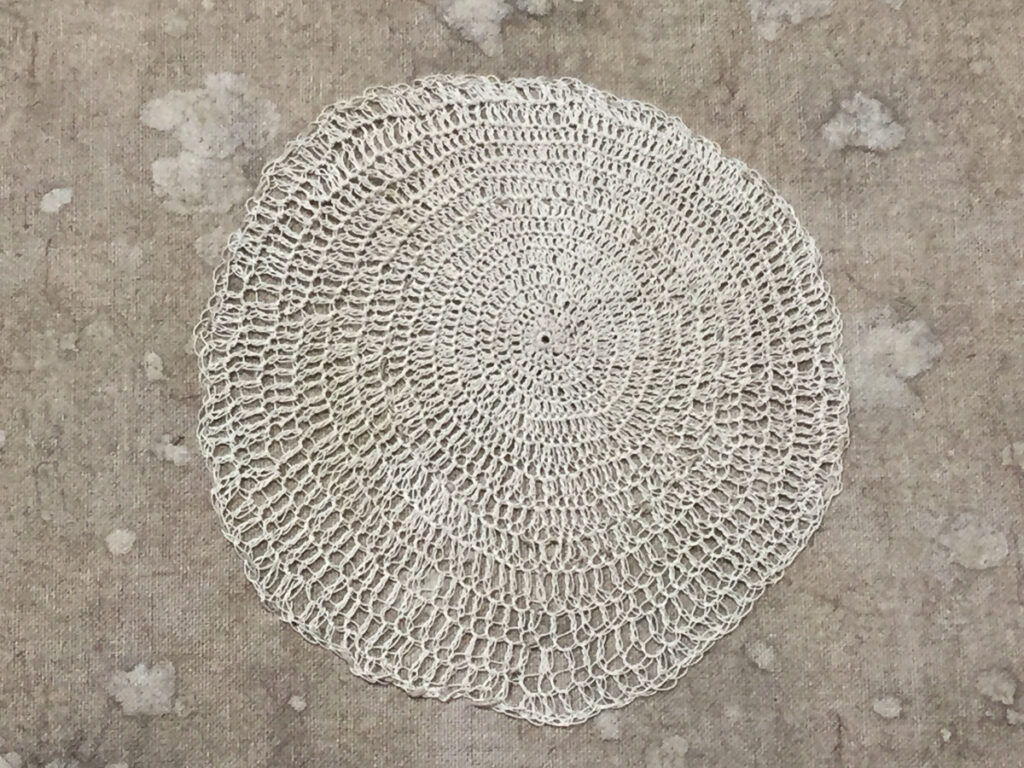

- Bryozoa as crochet.

- The finished work.

- The Bryozoan crust on the linen.

I had seen these patterns before, notably as a coating on barnacles that have attached to the underside of a floating studio on Bung Yarnda, where I spend a deal of time. Conceived and created as a focal point for a dynamic group of arts visionaries, it is known as FLOAT. The group, the movement and the floating studio share the name. The FLOAT studio is designed as an Arts Residency, aimed at bringing artists from around the world to stay for a time, learning to love this estuary while broadening our understanding of the arts and of the more than human world. The shared habitat nature of the mooring is teaching us all to find our place among the multitude of living creatures here. During the covid lockdowns, I became the self-appointed caretaker of the studio, spending many happy hours peering down a hatch into the underworld below the water’s surface. There I discovered a microcosm of growth and change. Little fishes feeding on the minuscule algae; dainty filter feeders combing the water for nutrients; unidentified swimmers darting in and out of the growth. There is a great deal of joy in the unknown. Curiosity sharpens observation. Imagination thrives on questions.

My aim was to reproduce something of the Bryozoan patterns onto the linen at a scale that could be interpreted by the viewer. I practiced drawing the structures on paper and stitching them on cloth, but I remained dissatisfied with the result. Handling the linen was destructive to the crusty little patterns; inevitable, I suppose, but I would like something of the original growth to remain. Drawing on the canvas is a clumsy affair, given the irregularities of the surface. Eventually I tried making a crochet lace piece that could be overlaid onto the linen. I am reasonably satisfied that this is the best solution.

Crochet is often my fall-back position. When I hark back to the generations of parents and grandparents who embedded me in this place, I remember the grandmothers and their domestic skills. Those ones who gathered tiny shells to hang from the edges of the lacy covers they made for their milk jugs. Those ones who looped endless threads together to craft exquisite bed covers of tiny crochet medallions. Those ones who brought their threads and their skills with them from the Old Country, to make their homes on this new land. It’s a long, long thread that stretches back into the forgotten stories of old Ireland and continues through my hands to tell the stories of this estuary. I am not skilled in those domestic crafts in the way my grandmothers were, but my hands know something of their heritage.

So, here it is. My Bryozoan linen. Steeped in the essence of time and place, it carries an idea of the systems of the Earth and our place within those precious patterns.

About Josephine Jakobi

I pursue my arts practice in my straw-bale studio on the edge of the Colquhoun Forest, a few kilometres from Lakes Entrance, which is situated on the far eastern end of the Gippsland Lakes, Victoria, Australia. My interest is in the Earth’s systems. Ecology and the vital role of plants in holding the systems in balance is an underlying theme in most of my art. All of my work is experimental, investigative and founded in my curiosity about the world around me. Photo credit, Jessee John.

I pursue my arts practice in my straw-bale studio on the edge of the Colquhoun Forest, a few kilometres from Lakes Entrance, which is situated on the far eastern end of the Gippsland Lakes, Victoria, Australia. My interest is in the Earth’s systems. Ecology and the vital role of plants in holding the systems in balance is an underlying theme in most of my art. All of my work is experimental, investigative and founded in my curiosity about the world around me. Photo credit, Jessee John.