Georgia Wallace-Crabbe’s documentaries reflect a monumental dialogue of elemental forces connecting China and Australia.

The Australian resource extraction industry has been called “the largest movement of earth in the planet’s history” (Guardian 2013). In 2010, deeply disturbed by the pro-coal actions of Australia’s federal and state governments in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence about the contribution of carbon emissions to climate change, I started a screen work to document the journey of coal across the planet. Living in Sydney’s south, in The Royal National Park (Bundeena), I saw coal trains rolling continuously along the rails to Wollongong and Port Kembla.

I visited China in the 1980s when it seemed almost pre-industrial, with beautiful mountains and picturesque landscapes. Backpacking with a Chinese friend and staying with her relatives, the trip educated me about China’s 4000+ years of continuous culture and challenged many Western preconceptions. In Xi’an, we visited a ninth-century Confucius Temple, “The Forest of Steles”, and the Qin Terracotta Warriors 210–209 BCE. We climbed sacred Mt. Ermei and, in the misty Three Gorges of the Yangtze River, saw a rocky outcrop the shape of a mythical maiden awaiting her long-lost lover over the seas. That boat trip from Chongqing to Wuhan is no longer possible, after the river was flooded for the Three Gorges Dam, forcing the relocation of 1.3 million people. We saw the “ten views of West Lake” in Hangzhou by bicycle and Suzhou’s famous walled gardens.

When I returned to China in 2007 to shoot New Beijing, a documentary about the rapid urbanisation of China, there was a stark contrast between the emerging modern China and the ancient traditions underpinning the culture. This change broke with 1980s Cultural Revolution China with its grey streets, Mao suits and bicycles, agricultural collectives and half-obliterated cultural heritage. We filmed the clearances of Beijing’s hutongs (alleys around the Forbidden City). We documented the sanitisation of the city’s history by demolishing Qing Dynasty courtyard houses and buildings that had been opium dens or brothels, which were rebuilt as Disney-like “Old Beijing Shopping Streets”.

I stayed in a hutong hotel in mid-winter, with snow on the ground, and met Chinese people from the provinces who still spoke fondly of Mao’s collectivised “dictatorship of the proletariat”. Old Beijingers showed me corners of the city earmarked for demolition and I acquired a taste of their nostalgia. They were passionate about their cultural history and surprised that an Australian had an interest in it.

The film New Beijing contrasted Beijing’s cultural heritage with the architectural gymnastics of the Beijing Olympics and its iconic buildings (the Birdsnest, Watercube, CCTV, etc). When it screened at international film festivals in New Zealand, Russia, China and Taiwan, it had a particular resonance for Chinese audiences.

This piece of jadeite carved into the form of a bokchoy cabbage was a decorative object in the Yung-ho Palace, but it was originally “planted” into a small enameled basin in the shape of a crab apple blossom with spirit fungi carved from red coral by its side. https://www.npm.gov.tw/exh96/Dazzling/large/e07.htm

Visiting Taipei’s National Palace Museum with fellow filmmakers, I saw artifacts taken from China by the retreating Nationalists in 1949. I was struck by the beauty, delicacy and “Zen” simplicity of the Song Dynasty ink scrolls, calligraphy, and ceramics. In works such as the famous carved jade, Jadeite Cabbage and Song Dynasty paintings such as those of Ma Yuan (Walking on a path in spring- pic), I saw similarities with the European Romantic Era, in the idealised treatment of nature and landscape.

The Song Dynasty (approx. 960–1279) was a period when the Chinese empire was at its largest, through trade and cultural exchange with the outside world. In the period, a post-Buddhist revival known as “Neo-Confucianism” anchored readings of the dialogues of Confucius to a dualism between “cosmic pattern” or “structure”(li 理) and “pneumas” – “life-force”or “spirit” (qi 氣 ). This moral cosmology differentiated it from the earlier traditions of Buddhism and Daoism. (633)

In 2011, undertaking a Doctorate of Creative Arts at Wollongong University, I started looking at China and Australia’s “interconnectedness” through mineral exports, seeking a post-colonial and intercultural approach. Close readings of contemporary environmental thought featured utilitarians such as Peter Singer and his concept of “the expanding circle”, eco-feminists Martha Nussbaum and Val Plumwood. This then led to anthropocene theorists Bruno Latour (Actor-Network Theory) and Timothy Morton (Object-oriented Ontology) and a “parallel” view of Western vs. Eastern culture (or Northern vs. Southern), influenced by the work of the Mexican-American theorist Manuel De Landa (a Post-Deleuzian).

Latour and Morton, among others, believe we have already entered the Anthropocene—a term coined by Eugene Stoermer and Paul Cruzten—for the current era, which began in the eighteenth century when humans are increasingly altering the Earth with climate change and other human-induced phenomena (Latour 2013).

De Landa’s text One Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (1997) presents a “geological” view of history, proposing that all structures that surround humans and form our reality (mountains, animals and plants, human languages, social institutions) are the products of specific historical processes. He writes that, “a small subset of geological materials (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nine other elements) formed the substratum needed for living creatures to emerge and that a small subset of organic materials (certain neurons in the brain) provided a subset for language.”

Parallel histories or processes were important to my multi-screen work, as the “small subset” includes the very elements that are essential for life but also the raw materials that are moving between Australia and China. As an Australian of European descent living in the Southern Hemisphere at the dawn of the “Chinese Century”, in an era that will be shaped by climate change, multiple perspectives and parallel histories are the only possible approach.

In seeking to combine an intercultural approach and a “parallel” histories approach to culture, nature, philosophical traditions, environment and aesthetics, I was drawn to the Daoist views of Nature to frame the creative work. The work of Chinese philosophy scholar Karyn Lai supported the proposition that Chinese philosophy might be helpful to environmental philosophy with its concepts of “inter-connectedness” and “inter-relationship”,

“Environment is more than the visible, more than the tangible, more than a matter of a quantifiable period of time or spread of space. It has deep structure, as well as deep process: this is the concept of Tao”. (K. Lai 2008)

Daoism is an ancient cosmology that explains the ”mystery of transformation and demonstrates that all change in the universe is cyclical rather than linear and therefore predictable” (Reid 1994). Older than Confucianism and Christianity, and less concerned with morality, Daoism uses the earth’s elements and materiality as symbols of balance and inter-relationship. Daoist texts from the fourth century BC, the Daodejing and the Zhuangze, underpin Chinese culture and subsequent Chinese schools of thought, including Confucianism and Buddhism, and this influence continues even after a century of change and revolution in China.

- A Mountain Path in Spring (山徑春行圖) Ma Yuan (馬遠, c.1160-1225), Song Dynasty (960-1279) Album leaf, ink and color on silk, 27.4 x 43.1 cm, National Palace Museum, Taipei

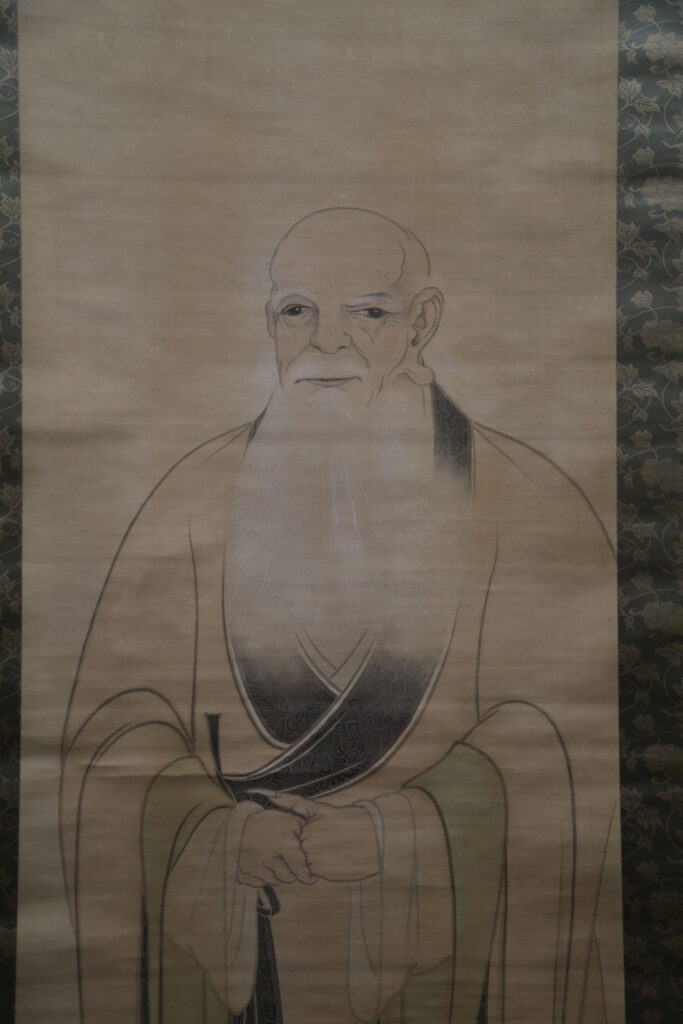

- Portrait of Lao Tze -the alleged author of the Daodejing (Photo by me) NPM

Cyclic change is the salient principle in the 3,000-year-old Daoist book of divination, the Yi-Ching (Book of Change), of which Jung was a devotee. Key Daoist principles Yin Yang (the Unity of Opposites) and Wu Xing, (the Five Elements) – Wood (木 mù), Fire (火 huǒ), Earth (土 tǔ), Metal (金 jīn) and Water (水 shuǐ), are widely recognised beyond Chinese culture. Despite the recent imposition of Marxism in China, it can be argued that this school of thought is culturally imbedded in China, with underlying ideals of group responsibility and balance with nature, which might offer a tool in intercultural communication between Chinese and Westerners in discussing the planet and the environment: a dialogue we must have, to avert the impending environmental crisis.

The Daoist concept of a circular universe, in constant flux with interconnected systems and cycles, was the key to the creative approach. This system with its central concepts of balance and interconnectedness and the cycles of nature in constant flux offered me a schematic approach for visualizing the concept of “interconnectedness”.

The video work uses the concepts of the Five Elements and the circular universe in dynamic flux as a framework to visualise the movement of materials between the two countries. The work proposes that Australia and China are equally implicated in climate change.

The stories of interconnectedness are told through this elemental framework: visualising the material flows of coal and iron ore and their transformation through combustion, manufacturing and environmental outputs from these processes. It uses the elements as a mode of telling the stories of this exchange. Observational footage from both countries follows the movement of materials across the planet.

The result is elemental: iron ore is Iron; coal(carbonised plant matter) is Wood; Wood and Metal frame the movement of coal and mineral ores; Fire is represented by combustion in coal-fired power generation, steel smelting and bushfire; Earth and Water are represented as environmental impacts, forest clearing and water pollution—evoking climate change and its impact on Australia’s fragile landscape.

Among the impressionistic images of industrial landscapes, there are a few speaking characters, to help the viewer contextualize the issues: Chris Pavich (National Parks and Wildlife) says, “where there is coal and there is a viable way to get it out, chances are they will mine it”. Anti-coal activist Nell Schofield, holds up a doughnut, saying: “Doughnut mining—they take the dough, we get the hole!” Yindjibarndi (Aboriginal) artist from the Pilbara, Loreen Samson says: “The iron-ore is the land! They are crushing our stories, our rock art”.

The five channels of video are projected onto five large screens loosely arranged as a pentagon; the resulting environment is immersive—as the screens surround the viewer giving them a sense of the monumental scale and impact of rapid growth in China. Images from many Australian locations show the impact of mineral extraction on communities, indigenous and non-indigenous, and environmental impacts in both countries evoke the global crisis. Moving through the exhibition space the viewer experiences the 26-minute five-screen work as an interactive experience.

The final work, The Earth and the Elements, offers a “big picture” viewpoint of humankind’s relationship with the natural environment.

Author

Georgia Wallace-Crabbe is a filmmaker of 30 years experience. She produced documentaries such as: Cultivating Murder (2018), These Heathen Dreams (2014), New Beijing: Reinventing a City (2009), about Beijing’s architecture and rapid redevelopment. Her multi-screen video work The Earth and The Elements was shown at UNSW Galleries in 2016, and Samstag Museum (SA) in 2017 as part of the “Troubled Waters” exhibition. A Doctorate of Creative Arts at Wollongong Uni (completed in 2015) saw a return to Visual Arts practice with the immersive multiscreen video work for galleries and a multiscreen installation for Museums. A university teacher of media, visual art and design, she is increasingly interested in expanded and immersive work using VR and 360. Her production company Film Projects, based south of Sydney, produces film, TV and other screen media. Visit www.filmprojects.com.au

Georgia Wallace-Crabbe is a filmmaker of 30 years experience. She produced documentaries such as: Cultivating Murder (2018), These Heathen Dreams (2014), New Beijing: Reinventing a City (2009), about Beijing’s architecture and rapid redevelopment. Her multi-screen video work The Earth and The Elements was shown at UNSW Galleries in 2016, and Samstag Museum (SA) in 2017 as part of the “Troubled Waters” exhibition. A Doctorate of Creative Arts at Wollongong Uni (completed in 2015) saw a return to Visual Arts practice with the immersive multiscreen video work for galleries and a multiscreen installation for Museums. A university teacher of media, visual art and design, she is increasingly interested in expanded and immersive work using VR and 360. Her production company Film Projects, based south of Sydney, produces film, TV and other screen media. Visit www.filmprojects.com.au