- Foufili Halagigie making a Lili Fakamanaia (Wall Hanging) for the Home AKL exhibition at her home in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland, New Zealand. Image taken by Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, May 21, 2012

- Foufili Halagigie making a Lili Fakamanaia (Wall Hanging) for the Home AKL exhibition at her home in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland, New Zealand. Image taken by Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, May 21, 2012

- Lakiloko Keakea making a Fafetu (Star shaped wall hanging) for the Home AKL exhibition at her home in Ranui, Auckland, New Zealand. Image taken by Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, May 4, 2012.

- Lakiloko Keakea making a Fafetu (Star shaped wall hanging) for the Home AKL exhibition at her home in Ranui, Auckland, New Zealand. Image taken by Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, May 4, 2012.

- Joana Monolagi making the first version of her “Pacific Circle” work for the Home AKL exhibition at her home in Pakuranga, Auckland, New Zealand. Image taken by Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, May 23, 2012

- Joana Monolagi making the first version of her “Pacific Circle” work for the Home AKL exhibition at her home in Pakuranga, Auckland, New Zealand. Image taken by Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai, May 23, 2012

“There is a Moana belief that we walk forward into the past and backwards into the future, both of which are constantly mediated in the changing present, where the past is put in front as a guiding principle and the future, situated behind, is brought to bear on past experiences.”[1]

Drawing on this belief spearheaded firstly by the late Professor “Epeli Hau’ofa and Hūfanga Professor “Okusitino Māhina, this paper will discuss and critique what I believe has been the mis-education[2] of Moana arts. I will draw specifically on my experience of working as one of three Associate Curators for Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki‘s “Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland” exhibition (2011 to 2012), and as a member of the Pacific Arts Committee (2011 to 2014) for Creative New Zealand, New Zealand’s national arts development agency. The Tongan worldview and perspective on arts will offer an alternative view and an example of the importance of emphasising Moana worldviews and perspectives when talking, researching or writing about our arts, which in turn empowers us as Moana peoples.

HOME AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland

Foufili Halagigie, Lakiloko Keakea, Joana Monolagi, Louisa Humphry, Kaetaeta Watson, Kolokesa Kulīkefu and Hūlita Tupou are all New Zealand based artists practicing in the here and now and are contemporary artists of Pacific heritage.[3] Or are they? According to the New Zealand mainstream arts community they are not contemporary artists, they are “heritage artists” that produce “traditional” works and “handicrafts”!

Edith Amituana’i, Graham Fletcher, Tanu Gago, Niki Hastings-McFall, Lonnie Hutchinson, Ioane Ioane, Leilani Kake, Shigeyuki Kihara, Jeremy Leatinu’u, Andy Leleisi’uao, Janet Lilo, Ani O’Neill, Sēmisi Fetokai Potauaine, John Pule, Greg Semu, Siliga David Setoga, Paul Tangata, Angela Tiatia, Teuane Tibbo, Sopolemalama Filipe Tohi and Jim Vivieare were either formerly based or are currently New Zealand based artists.[4] Apart from Tibbo and Vivieare who have passed on, these artists are practicing in the here and now and are contemporary artists of Pacific heritage. According to the New Zealand mainstream arts community, they are contemporary artists.

All of these artists were included in the Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage (Home AKL) exhibition held at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (AGG). Despite the exhibition team’s decision to refer to all artists involved as “contemporary” artists; it was interesting to read the commentary surrounding the exhibition after it opened. There was a general ambivalence surrounding the inclusion of the so called “heritage” artists and their works in Home AKL. Whether it was the absence of any mention or just a passing reference to these artists and their works, speaks volumes in itself. When they were mentioned, it was always under the descriptive terms of “traditional” or “heritage” and “handicraft”. The fact that these terms were not included in any of the Home AKL media releases or in any of the labels in the exhibition, is an indication of how the New Zealand-wide mainstream arts community, including our Moana arts community, have problematically internalised these definitions in association to works that are made by our so called “heritage” artists.

Some of these comments include:

“Also as a reference point is a large Tongan tapa cloth which is the most traditional of the works in the show and the most abstract.”[5]

“The links with abstract art can also be seen in the traditional offerings by Joana Monolagi, Lakiloko Keakea and Foufili Halagigie with their circular works of traditional and modern materials.”[6]

“The curatorial team…have also tried to assert that the traditional arts remain contemporary.”[7]

“…the inclusion of “traditional” works in Home AKL did the “contemporary” artists a disservice…”[8]

“I wasn’t drawn to the heritage arts section in the show…”.[9]

“They are memories of home captured on canvas, photography and handicraft…Fijian artist Joana Monolagi prints her memory of home in her handicraft Pacific Circle.”[10]

The terms “traditional”, “heritage” and “handicraft” are so ingrained in the vocabulary that were used to describe “heritage” artists and their artworks in Home AKL. It was even embedded in the vocabulary of members of our exhibition and curatorial team. I also freely used these terms up until I started working at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) in 2004. It was at Te Papa and in particular working closely with Sean Mallon, Senior Curator Pacific Cultures, and the Pacific team that I came to truly understand the problems associated with the term “traditional” when used to talk about our arts. Mallon later explained that it was actually Professor Albert Wendt who had suggested that they stop using the term “traditional art” in 1994 when he was a member of an Auckland based Pacific Advisory Committee that was assembled for Te Papa. In an article written by Mallon titled “Against Tradition” published in 2010,[11] he explains the history of Wendt’s suggestion and the significant impact that it has had in shifting the use of terminologies in relation to Moana art at Te Papa. In this article Mallon writes that:

“Wendt was concerned that we decolonize the language we use in our exhibitions, particularly as the exhibition team included people of Pacific Island descent. In his view, the word ‘traditional’ as used in categories such as ‘traditional arts’ and ‘traditional practices’ was the vocabulary of Western ways of writing about and cataloguing indigenous peoples. We in museums had bought into it, and our communities had internalized it. These terms obscure our histories and creativity and give the impression our cultures are static and unchanging…”. [12]

My time at Te Papa, combined with my current independent work as a curator, writer and arts adviser, being informed by a Tongan perspective on arts, has made me conscious and critical of terminologies that are currently used to define our Moana arts. My involvement with the Home AKL exhibition was specifically to contribute to the “heritage arts” component of the show. From the outset I was critical of the term “heritage” for the same reasons that Wendt found with the term “traditional”, but also because I felt that it devalued the work of artists categorised under this term. I offered the Tongan worldview and perspective of arts as a means of highlighting the problems with this term where art forms defined as “heritage arts” are actually defined in Tonga as our fine arts.

For example, Tongan arts is classified into three genres: tufunga (material), faiva (performance) and nimamea’a (fine) arts,[13] where tufunga includes painting and tattooing; faiva includes music and dance and nimamea’a includes weaving and tapa making. The Tongan classification of art is highly refined in terms of its plural, holistic, circular and inclusive nature in opposition to the Western / New Zealand European perspective where Moana arts are classified in singular, linear and spatio-temporal ways such as past, present and future, hence the distinction of artists and art forms into “traditional’, “heritage” and “contemporary”. Over time and space the three genres of the Tongan arts classification remains the same despite the use of new materials, technology and the inclusion of new art practices. This is because the particular knowledge and skills applicable to each of the three genres remains the same.

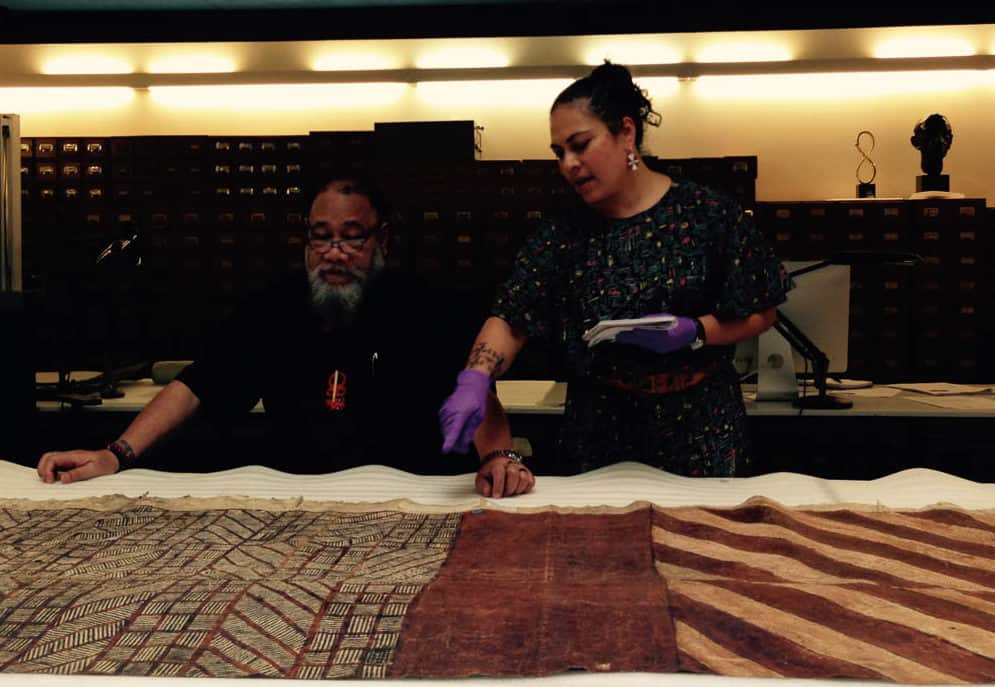

The various art forms under nimamea’a such as tapa and weaving as well as embroidery and crochet are our Tongan fine arts. This differs greatly from a Western / New Zealand European perspective where our fine arts are defined using terms such as “traditional’, “heritage” or “handicraft”. A case in point was the largest work in the Home AKL exhibition, the ngatu tā’uli (black-marked barkcloth) made by an unknown kautaha koka’anga (Tongan women’s barkcloth making collective). Initially this work had a Western aesthetics imposed on it to make it “art” and then loaded with cultural significance through its associated stories to give it authenticity and added value. It was on this basis that it passed through various owners before being housed by AAG, and since Home AKL, it is now part of AAG’s collection. The questionable provenance and research to date associated with this ngatu tā’uli was not revealed until I questioned its authenticity. It was inaccurate from a Tongan cultural context and was defined and interpreted from a Western perspective and worldview. It is interesting and patronising when commentary and research to date about this ngatu tā’uli has either imposed a Western aesthetics or compared the work to a Western artist, merely so that it can be considered “art”. However, I hope that the interpretation from a Tongan worldview that I provided for this ngatu tā’uli provides a better understanding and appreciation of this work for what it is and has always been, an example of our Tongan fine arts.[14]

The Tongan perspective of art also challenges the use of “contemporary” because along with the other terms already mentioned, it leads to compartmentalising art forms and risks generating misunderstanding and misinterpretation. I felt that this was the case when “heritage arts & artists” were distinguished from “contemporary arts & artists” in our discussions of the Home AKL artists. I argued that if we were going to use a terminology then “contemporary” would be the most adequate and equitable term to define ALL of the Home AKL artists because they are all practicing artists in the here and now, despite some using weaving and embroidery and others using photography and video. To the credit of AAG, who had the initiative to include the artists who produced these works in the first place, then follow through with commissioning five new works by them (three of which are now in their collections), and then doing away with the use of “heritage” to describe them and their works, was commendable, and a much needed departure from the current status quo.

Although my work is informed by a Tongan worldview and perspective, I was very careful not to impose it on the definition and interpretation of the various art forms of the different island groups that I worked with, which included Fiji, Kiribati, Tuvalu and Niue. What Mallon wrote about our communities “internalising” Western terminologies to define our arts was very much the case when talking with these artists and translators. It wasn’t until I asked them to describe their art forms and art practices in their own languages and from their own worldviews and perspectives that I felt I was closer to a more accurate interpretation of their works. It is only natural that these artists have come to use terminologies that have been imposed on defining them as practitioners and their works. However, when such terminologies serve to marginalise these artists and their art forms then we need to ask ourselves: Do we want to contribute and continue this cycle of the mis-education of our Moana arts?

There is an onus on us as curators, writers, artists, academics and arts organisations to be conscious and critical of terminologies that we use to define Moana arts, which in turn informs our audiences. It is up to us to choose whether we want our audiences to continue using terminologies that perpetuate stereotypes about our arts or one that is better informed on the nuances of our diverse art forms and our Moana worldviews. This will hopefully go a long way in ensuring that we avoid careless mistakes from commentary about the Home AKL exhibition, where the Tongan ngatu tā’uli was referred to as a siapo, which is the Sāmoan word for tapa, and the names of some our artists of Pacific heritage were misspelt, such as Leilani Kake, Siliga David Setoga and Teuane Tibbo’s names.

Creative New Zealand Pacific Arts Committee

Institutions like Creative New Zealand (CNZ) play a huge part in influencing terminologies that are used to define Moana arts. Prior to joining the CNZ Pacific Arts Committee (PAC) I had experienced first-hand during the various projects I was involved in, the negative effects that terminologies such as “heritage’, “traditional” and “handicraft” have, on how works by Moana women artists are marginalised and often not regarded as “art”. CNZ is also contributing towards “internalising” the use of terminologies such as “heritage” to define and categorise Moana arts. It is interesting to note here that during the same period that Wendt had affected change at Te Papa, by doing away with the term “traditional”, he also had advisory and governance roles in CNZ. During his time their the funding category “Traditional Arts” was retitled “Heritage Arts”.[15] So the current use of “Heritage Arts” by CNZ is attributed to Wendt. I would argue that despite the change of terminologies from “traditional” to “heritage” within CNZ in the 1990s, the mind-set is still much the same now in 2013, which is akin to being taken “out of the frying pan and into the fire.”

I do acknowledge that CNZ has incorporated the key concept of “Kaupapa Pasifika” which:

“…seeks to reflect the unique context of Aotearoa-based Pasifika communities and to help these communities express a set of deeper cultural values and world views that are specific to their own experiences as Pasifika peoples living in New Zealand.”[16]

My critique is that the concept and practice of Kaupapa Pasifika is then superficial when it comes under the wider CNZ umbrella which imposes a Western / New Zealand European framework on how Moana arts are defined, perceived and understood. My mission upon joining the CNZ PAC in September 2011 was to see how I could change these terminologies. However, two years into the role I came to the realisation that while it is important to have appropriate terminologies that are aligned with Moana perspectives and worldviews, it is vital to also address the mis-education of Moana arts in order to affect a real shift from the current mind-set.

As a staunch advocate for artists and art forms under the definition of “heritage” within the CNZ PAC, there has been some progress made in terms of highlighting the institutional contradictions and lack of understanding and acknowledgement of the true value of artists and art forms under the “heritage arts” category. However, there is still more work to do to better inform the current mis-education of Moana arts within CNZ, and in turn the wider New Zealand arts communities, including our Moana arts community. “Heritage Arts” is one of CNZ’s priorities for Moana arts and as one of the PAC members, Tigilau Ness, eloquently articulated “A tree may branch and grow in any number of directions, and if you water the roots of the tree it will grow. The heritage arts are the roots of all Pacific arts.’[17] The metaphor of a tree is quite apt in capturing the essence of Moana perspectives and worldviews. It illustrates the interrelationships and interdependencies of the different parts of the tree along with external elements that are essential for its nurturing, survival and growth. So, when I am asked whether a particular monetary value is sufficient for “heritage” arts, my question would be “Is this the value of the roots of ALL Moana arts?”

I acknowledge that there are other problematic terminologies, such as the term “Pacific”, which cannot be covered in the scope of this paper. I also accept that there is relevance for terminologies when applied to works by New Zealand raised or born artists of Pacific heritage who are inspired directly from their urban environment and experiences. However, I do find it a contradiction when artists of Pacific heritage that are practitioners of various art forms brought from their respective homelands to New Zealand, such as tīvaevae, tapa and weaving, have expanded these art forms through adaptation and innovation in a new environment, are defined as “heritage” artists and marginalised. On the other hand, artists that draw directly from “heritage” art forms and art practices are distinguished and elevated as “contemporary” artists. From a Moana perspective, it is illogical to have artists that take inspiration from a particular art form and practice elevated over the source itself.

In conclusion I would like to refer back to the “…Moana belief that we walk forward into the past and backwards into the future, both of which are constantly mediated in the changing present, where the past is put in front as a guiding principle and the future, situated behind, is brought to bear on past experiences.” There is great wisdom and insight in this belief that would greatly benefit Moana arts. If applied there is an onus on us in the present to ensure that we are not only informed by the refined knowledge and skills of the past, but that we make use of what is beautiful and permanent in our Moana arts as a strong foundation for the future. If we were doing this today the so called “heritage” artists—who are the holders of the refined knowledge and skills of the past and are the roots of ALL Moana arts—would be in front of us rather than behind and elevated rather than marginalised. The mis-education of Moana arts comes from our reluctance today to genuinely privilege Moana perspectives and worldviews of our arts. It is only when we do this that we will be able to effect real change in people’s mind-set.

Acknowledgements

There is a Tongan proverb that says “Koloa ‘a Tonga ko e fakamālō” meaning “The treasure of Tonga is in saying thank you.” I therefore would like to take this opportunity to thank those that contributed to the content of my paper and assisted in getting me to the 11th Pacific Arts Association (PAA) International Symposium in Vancouver, Canada, August 2013. I would like to acknowledge the Friedlander Foundation and Rose Dunn for their financial contribution towards my travel to attend and participate in the 11th PAA. A huge thank you to Ron Brownson for his continued support and to Auckland Art Gallery for providing images from the Home AKL opening and exhibition that I used in my presentation in Vancouver. Thank you to Makerita Urale for providing information for the Creative New Zealand component of this paper. Thanks also to Sean Mallon for directing me to a chapter he wrote that provided the foundation of an earlier presentation of which this paper drew from. Many, many thanks to Ema Tavola, Leilani Kake, Margaret Aull and Rosanna Raymond for sharing living costs while in Vancouver. To my father, Hūfanga Professor “Okusitino Māhina, thank you for your wisdom, guidance, inspiration, rigour and critical talanoa. Thank you to Mele Ha’amoa Māhina “Alatini for reading and editing my paper. And last but not least, to my husband and title whiz Kenneth Tuai and our girls Meleseini Haitelenisia Fifita “O Lakepa Lolohea “Fetu’u” Tuai and Akesiumeimoana Tu’ula-i-Kemipilisi Tupou Tuai, thank you for your continuous love and support which enables me to do what I do.

This paper was initially presented to a community audience in Otara, South Auckland, New Zealand. One of the feedback from the audience was for me to use and privilege the indigenous, localised name Moana over the foreign, imposed labels Pacific and Oceania.

Bibliography

Brownson, Ron, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, Albert L Refiti, Ema Tavola, Nina Tonga. Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Creative New Zealand Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa, accessed Sunday 28 July 2013, http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/en/getting-funded/glossary#top

Creative New Zealand Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa. Creative NZ Pacific Arts sector consultation and review 2013 (2013): 5, accessed Friday May 20, 2014, http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/assets/paperclip/publication_documents/documents/324/original/pacific_arts_report_2013_final.pdf?1386621091

Satele, Daniel M. “Who’s Home? Home AKL at Auckland Art Gallery.” Art New Zealand, no. 143 (Spring 2012): 42-47.

Daly-People, John. Pacific artists find home in new exhibition, Monday July 9, 2012, accessed Wed July 31 2013, http://www.nbr.co.nz/article/pacific-artists-find-home-new-exhibition-123065

Gifford, Adam. Home AKL: Celebrating Pacific Art, Saturday July 14, 2012, accessed Wed July 31, 2013, http://www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/news/article.cfm?c_id=1501119&objectid=10819357

Hau’ofa, “Epeli. “Epilogue: Pasts to Remember.” In Remembrance of Pacific Pasts: An Invitation to Remake History, edited by Robert Borofsky, 453 – 471. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2000.

Māhina, Hūfanga Professor “Okusitino and K. U. Māhina-Tuai editors. Hinavakamea and Tunavakamea as Material Art of Steel-cutting: Intersection of Connection and Separation. LRS Publishing [NZ]: in association with the Ministry of Tourism, Kingdom of Tonga, 2012.

Māhina, “Okusitino, J. Dudding, and K. U. Māhina-Tuai, editors. Tatau: Fenapasi “o e Fepaki / Tatau: Symmetry, Harmony and Beauty: The Art of Semisi Fetokai Potauaine. LRS Publishing [in conjunction with Museum of Archaeology and Antropology, Cambridge University, UK]: Auckland, 2010.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa. “Looking Backwards Into Our Future: Reframing “Contemporary” Pacific Art.” In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Brownson, Ron et.al., 31 – 36. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa. “Louisa Humphry, Kaetaeta Watson”. In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Brownson, Ron et.al., 37 – 38. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa. “Kautaha Koka’anga”. In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Brownson, Ron et.al., 49 – 51. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa. “Lakiloko Keakea”. In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Brownson, Ron et.al., 52 – 53. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa. “Kolokesa Kulīkefu, Sēmisi Fetokai Potauaine, Hūlita Tupou”. In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Brownson, Ron et.al., 63 – 65. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa. “Joana Monolagi.” In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Brownson, Ron et.al., 82 – 83. Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2012.

Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa Uafā and Manuēsina “O. Māhina. Nimamea’a: The Fine Arts of Tongan Embroidery and Crochet. Objectspace, Auckland, 2011.

Mallon, Sean, “Against Tradition.” In The Contemporary Pacific: a journal of island affairs 22, Issue 2 (2010): 362-381.

Potauaine, Sēmisi Fetokai and “Okusitino Māhina, “Kula mo e “Uli: Red and Black in Tongan Thinking and Practice.” In Tonga: Land, Sea and People, edited by Tangikina Moimoi Skeen and Nancy L. Drescher, 194 – 216. Tongan Research Association, Nuku’alofa Tonga: Vava’u Press, 2011.

Potauaine, Sēmisi Fetokai, “Tectonic of the Fale: Four Dimensional, Three Divisional.” Master of Architecture Thesis, The University of Auckland, New Zealand, 2010.

Tagata Pasifika. Home AKL Art Exhibition, published July 25, 2012, accessed Wed July 31, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=imD-L5gXnX4

Tonga, Ane. Happy to be Home AKL, blog posted Tuesday 24 July 2012 10.27am, accessed Wed July 31 2013, http://anetonga.blogspot.co.nz/2012/07/check-out-my-review-on-latest.html

Notes

[1]. Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, “Looking Backwards Into Our Future: Reframing ‘Contemporary’ Pacific Art.” In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Ron Brownson, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, Albert L Refiti, Ema Tavola and Nina Tonga, (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki: Auckland, N.Z. 2012), 34. This quote includes a slight addition from the source of the original quote, Hūfanga Professor ‘Okusitino Māhina, November 2012. Also refer to ‘Epeli Hau’ofa, “Epilogue: Pasts to Remember.” In Remembrance of Pacific Pasts: An Invitation to Remake History, edited by Robert Borofsky, (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), 453 – 471.

[2]. The title of this paper was provided by Kenneth Tuai and inspired by a book originally published in 1933 titled The Mis-Education of the Negro by Dr Carter G. Woodson. Woodson was the second African American to earn a PhD from Harvard University and afterwards dedicated himself to the field of African-American history and is often known as the “Father of Black History”. His book focuses on the Western indoctrination system and African-American self-empowerment, accessed, Saturday 27th July 2013, http://www.biography.com/people/carter-g-woodson-9536515?page=1#writing-%27mis-education-of-the-negro%27

[3]. Refer to Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, “Foufili Halagigie”, “Louisa Humphry”, “Kaetaeta Watson”, “Kautaha Koka’anga”, “Lakiloko Keakea”, “Kolokesa Kulīkefu, Sēmisi Fetokai Potauaine, Hūlita Tupou” & “Joana Monolagi.” In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Ron Brownson et al., (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki: Auckland, N.Z. 2012), 26 – 27, 37 – 38, 49 – 51, 52 – 53, 63 – 65 & 82 – 83.

[4]. Refer to Ron Brownson et.al., Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki: Auckland, N.Z. 2012).

[5]. John Daly-People, Pacific artists find home in new exhibition, Monday July 9, 2012, accessed Wed July 31 2013, http://www.nbr.co.nz/article/pacific-artists-find-home-new-exhibition-123065

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. Adam Gifford, Home AKL: Celebrating Pacific Art, Saturday July 14, 2012, accessed Wed July 31 2013, http://www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/news/article.cfm?c_id=1501119&objectid=10819357

[8]. Daniel M. Satele “Who’s Home? Home AKL at Auckland Art Gallery” Art New Zealand, Number 143 (Spring 2012), 43.

[9]. Ane Tonga, Happy to be Home AKL, blog posted Tuesday 24 July 2012 10.27am, accessed Wed July 31 2013, http://anetonga.blogspot.co.nz/2012/07/check-out-my-review-on-latest.html

[10]. Tagata Pasifika, Home AKL Art Exhibition, published July 25, 2012, accessed Wed July 31 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=imD-L5gXnX4

[11]. Sean Mallon, “Against Tradition” The Contemporary Pacific: A Journal of Island Affairs 22, 2 (2010), 362-381.

[12]. Ibid. 369.

[13]. Refer to ‘Okusitino Māhina, Jocelyne Dudding and Kolokesa U. Māhina, editors., Tatau: Fenapasi ‘o e Fepaki / Tatau: Symmetry, Harmony and Beauty: The Art of Semisi Fetokai Potauaine, (LRS Publishing [in conjunction with Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge University, UK]: Auckland, 2010); Sēmisi Fetokai Potauaine, “Tectonic of the Fale: Four Dimensional, Three Divisional.” Masters of Architecture Thesis, The University of Auckland, 2010; Sēmisi Fetokai Potauaine and ‘Okusitino Māhina, ‘Kula mo e ‘Uli: Red and Black in Tongan Thinking and Practice.” In Tonga: Land, Sea and People, Tangikina Moimoi Skeen and Nancy L. Drescher editors. (Tongan Research Association, Nuku’alofa Tonga: Vava’u Press, 2011); Kolokesa Uafā Māhina-Tuai and Manuēsina ‘O. Māhina, Nimamea’a: The Fine Arts of Tongan Embroidery and Crochet (Objectspace, Auckland, 2011); Hūfanga Professor ‘Okusitino Māhina and Kolokesa Uafā Māhina-Tuai editors., Hinavakamea and Tunavakamea as Material Art of Steel-cutting: Intersection of Connection and Separation (LRS Publishing [NZ]: in association with the Ministry of Tourism, Kingdom of Tonga, 2012).

[14]. Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, “Looking Backwards Into Our Future: Reframing ‘Contemporary’ Pacific Art.” In Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland, Ron Brownson et. Al., (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki: Auckland, N.Z. 2012), 31 – 36.

[15]. Refer to footnote 4. in Mallon, “Against Tradition”, 378.

17. Creative NZ Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa, accessed Sunday 28 July 2013, http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/en/getting-funded/glossary#top

[17]. Creative New Zealand Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa, Creative NZ Pacific Arts sector consultation and review 2013 (2013): 5, accessed Friday May 20, 2014, http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/assets/paperclip/publication_documents/documents/324/original/pacific_arts_report_2013_final.pdf?1386621091

Author

Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai is an independent curator, arts advocate and published author of Tongan heritage living in Aotearoa New Zealand. She champions a holistic and cyclical perspective of Moana Oceania arts that is rooted in indigenous knowledge and practice. She works throughout every level of the Moana Oceania arts community from museums and galleries to grassroots community organisations. At the heart of Kolokesa’s practice has been her strong foundation of Tongan indigenous knowledge and practice. This informs her understanding and appreciation of Moana Oceania arts and her relationships and collaborations with artists from different island nations. She has been an advocate of Moana Oceania artists that are agents in maintaining, preserving and evolving the arts of their homeland in Aotearoa New Zealand. This has been through exhibitions, events, commissioned works, conferences and publications. Kolokesa is a co-author of the first book on Tongan arts from a Tongan perspective. She is also researching and a co-editor of a major new history of craft in Aotearoa New Zealand and the wider Moana Oceania. Portrait image is with her baby sister (Hikule’o Fe’amoeako ‘i Kenipela Melaia Māhina) after her graduation last year where she is wearing some of our Moana and Tongan garlands

Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai is an independent curator, arts advocate and published author of Tongan heritage living in Aotearoa New Zealand. She champions a holistic and cyclical perspective of Moana Oceania arts that is rooted in indigenous knowledge and practice. She works throughout every level of the Moana Oceania arts community from museums and galleries to grassroots community organisations. At the heart of Kolokesa’s practice has been her strong foundation of Tongan indigenous knowledge and practice. This informs her understanding and appreciation of Moana Oceania arts and her relationships and collaborations with artists from different island nations. She has been an advocate of Moana Oceania artists that are agents in maintaining, preserving and evolving the arts of their homeland in Aotearoa New Zealand. This has been through exhibitions, events, commissioned works, conferences and publications. Kolokesa is a co-author of the first book on Tongan arts from a Tongan perspective. She is also researching and a co-editor of a major new history of craft in Aotearoa New Zealand and the wider Moana Oceania. Portrait image is with her baby sister (Hikule’o Fe’amoeako ‘i Kenipela Melaia Māhina) after her graduation last year where she is wearing some of our Moana and Tongan garlands